Dear Capitolisters,

A minor kerfuffle recently erupted after U.S. regulators recommended Pfizer booster shots for certain “at risk” Americans, and Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla announced that this might become an annual occurrence. Many people on the right and the left are upset, it seems, that the giant pharmaceutical multinational stands to earn billions dollars in profits from vaccines and boosters this year and beyond.

And you know what? I’m upset too—because it should be way, way more.

Yes, Pfizer (and Others) Will Profit

Before we get to that, however, let’s rehash the basics. Early last year, when several global vaccine manufacturers were taking government subsidies and vowing forgo profits on any vaccine developed, Pfizer famously did neither. (Moderna took some cash but also said it would profit; Pfizer also has pledged to donate doses and not profit on sales to developing countries.)

Now we’re starting to get an idea of just how big those profits will be. According to the Associated Press, Pfizer has told shareholders that it anticipates receiving about $33.5 billion in revenue this year from its COVID-19 vaccine, and earning a pre-tax adjusted profit margin in the “high 20s” from those sales. Boosters, per a quoted expert, would bring in about $26 billion more (for both Pfizer and BioNTech, which split the proceeds) if they’re eventually approved for all Americans. This translates to about $9 billion in Pfizer profits this year (vaccines plus boosters), and maybe as much as $20 billion next year (about $7 billion for just boosters plus billions more for initial vaccine treatments). BioNTech, meanwhile, reported €3.9 billion (about $4.5 billion) in profits for the first half of 2021, and forecasts even higher sales for the next year.

Things die down a bit after 2022, however: Analysts forecast just $6.6 billion in 2023 revenue for the Pfizer/BioNTech shot, mostly from boosters (a little under $2 billion in profits, again split between both companies), and “the annual market settling at around $5 billion or higher, with additional drugmakers competing for those sales.” There’s still a ton of uncertainty regarding the need for annual boosters and the number of eventual competitors in any such market, but the near-term outlook for the “Big 3” mRNA vaccine makers is pretty clear: Pfizer’s going to make tens of billions of dollars in pre-tax profit on these jabs, and BioNTech and Moderna will also benefit handsomely.

And Those Profits Will Be Good

Contrary to the populist hysteria, however, we should be cheering these profits—and the companies’ rising stock valuations—for several reasons. For starters, the firms’ financial good fortunes will give them the ability and incentive to invest in additional COVID-19 vaccine production capacity and in other innovative medicines unrelated to COVID. This is essentially the flipside of research showing that corporations facing higher taxes tend to invest less in research and development—just as having less money to spend might mean lower innovation, having more cash would tend to do the opposite.

And that’s precisely what’s happening with BioNTech and Pfizer:

[BioNTech’s] soaring fortunes — with its shares rising fourfold in the past year — have allowed for a big push into other medical research. The Mainz-based start-up reported a cash position of €914.1m and said it aimed to plough €950m-€1.5bn into research and development in the second half of the year.

Among its top priorities will be oncology research. The company is working on 15 candidates for cancer therapies and has also vowed to devote resources to developing malaria and tuberculosis vaccines.

BioNTech and Pfizer expect manufacturing capacity to reach 4bn doses next year. The two companies have continued their research on an mRNA vaccine for influenza, and BioNTech said human trials would begin in the next quarter.

Moderna also plans to use its profits and market capitalization to expand COVID vaccine production and create drugs to treat heart disease, cancer, rare genetic conditions, emerging viruses (e.g., Zika), and “hard-to-target pathogens such as HIV.” Excellent.

Second, the COVID vaccine makers’ profits should encourage others to produce vaccines, as the AP notes:

Pfizer said in July it expects revenue from its COVID-19 vaccine to reach $33.5 billion this year, an estimate that could change depending on the impact of boosters or the possible expansion of shots to elementary school children.

That would be more than five times the $5.8 billion racked up last year by the world’s most lucrative vaccine — Pfizer’s Prevnar13, which protects against pneumococcal disease.

It also would dwarf the $19.8 billion brought in last year by AbbVie’s rheumatoid arthritis treatment Humira, widely regarded as the world’s top-selling drug.

This bodes well for future vaccine development, noted Erik Gordon, a business professor at the University of Michigan. Vaccines normally are nowhere near as profitable as treatments, Gordon said. But the success of the COVID-19 shots could draw more drugmakers and venture capitalists into the field. “The vaccine business is more attractive, which, for those of us who are going to need vaccines, is good,” Gordon said.

That innovators might be driven by others’ financial success—and thus have their own “profit motives”—is a pillar of U.S. patent policy, as explained in a recent economics paper summarizing the literature:

Patents aim to stimulate the development of new products and processes. Under standard patent theory, they accomplish this in two ways. First, by allowing inventors a limited‐term right to exclude others, patents generate profits associated with market power. These profits are the incentive needed for inventions to be developed and to allow firms to appropriate returns from research and development (R&D)….

The extent to which innovation actually is driven by intellectual property protections and the profit motive is hotly debated in the economics field, but the aforementioned survey shows that it does seem to matter for pharmaceuticals (and less so for other industries). Thus, more profits for Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna should attract others to jump into the field and achieve the same.

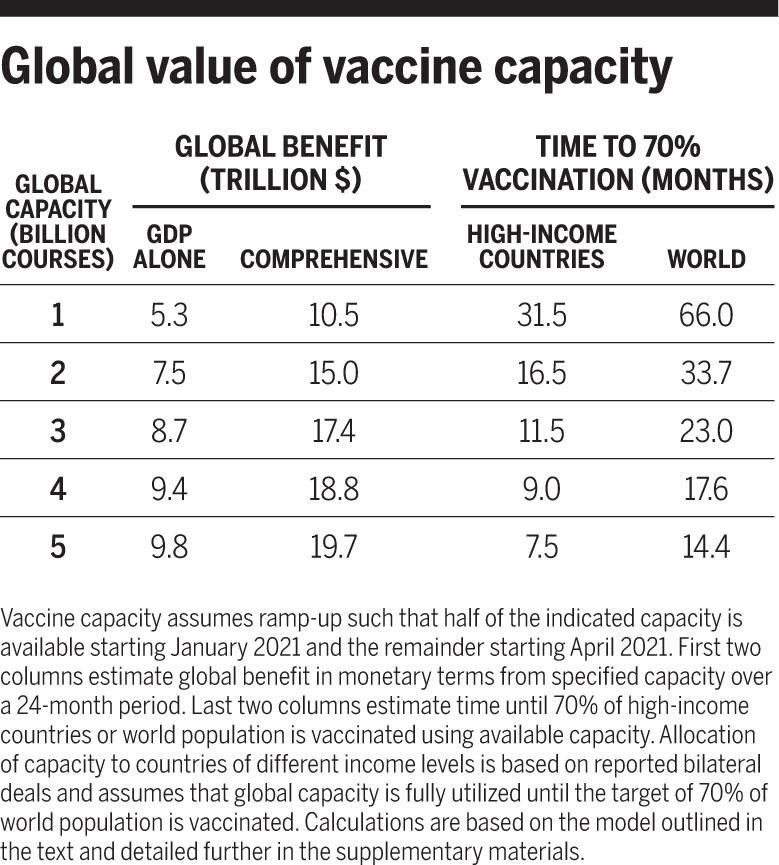

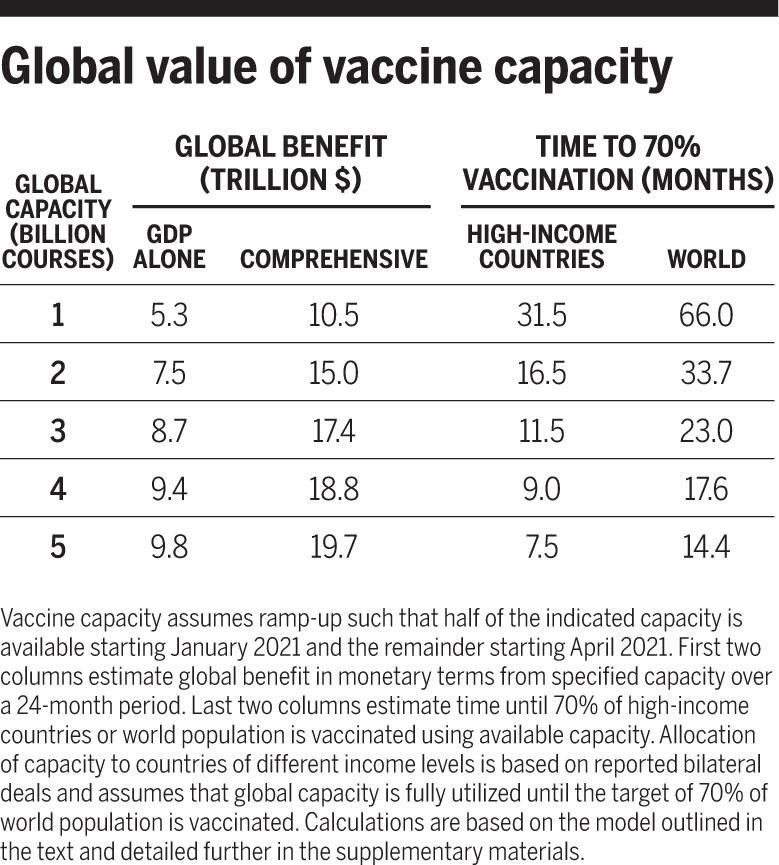

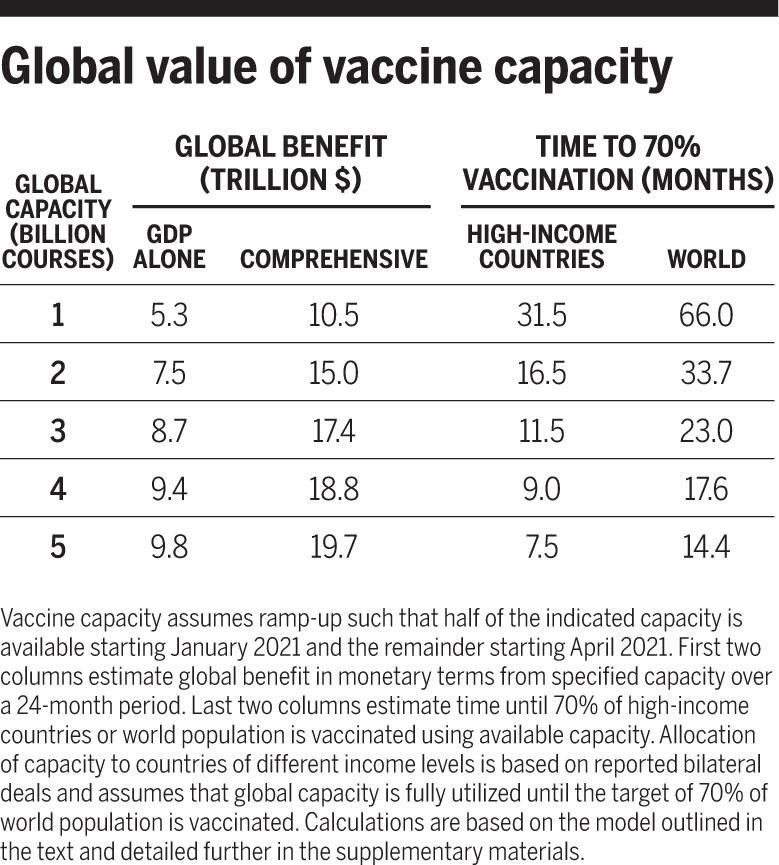

Third, it’s almost certain that any profits enjoyed by the vaccine makers’ founders, executives, and shareholders will be dwarfed by the vaccines’ benefits to everyday Americans and other humans around the world—and by large margins. A March 2021 paper in Science, for example, estimated that widespread proliferation of the COVID vaccine would increase global GDP alone by trillions of dollars, with the broader societal benefits adding trillions more. This makes sense, as the authors note, when you consider recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates of $12 trillion in global GDP losses from the pandemic during 2020–2021 and other studies calculating even larger values—for the United States and more broadly—when adding to GDP intangible things like health and education losses.

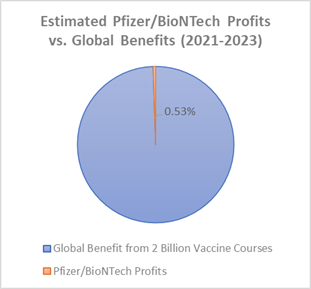

Such estimates are obviously rough, but they do allow us to have some much-needed perspective—and a back-of-the-napkin calculation—about the scale of the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna profits in relation to the overall benefits that these companies’ sales have provided the world. Assuming, for example, that BioNTech/Pfizer, which plan to have vaccine production capacity of 4 billion doses (2 billion courses) in 2022, each make even as much as $40 billion in profit by 2023 (a liberal guess given the data above), that would be only about 1 percent of the $7.5 trillion in global GDP gained—and slightly more than 0.5 percent of the $15 trillion in total social benefits—from those 2 billion courses:

Surely, these are rough calculations that don’t account for other vaccine proliferation and COVID mitigation efforts (including those by governments at no cost to the vaccine makers), but they hopefully give us an idea of just how silly it is to complain that Pfizer, BioNTech, and Moderna are making a few billion in profits from their literally-world-changing efforts. And that’s especially the case for Pfizer, which refused upfront U.S. government money and did most of the heavy lifting—testing, development, manufacturing, etc.—itself, while taking U.S. government payments for only finished, approved vaccine doses at a reasonable price.

The startling numbers above are also pretty consistent with the economics literature on how the benefits of innovations are split between innovators and consumers. According to a classic paper from Nobel laureate William Nordhaus, for example, the gains from innovations like computers, software, and telecommunications are mostly enjoyed by you and me (the “consumer surplus”), not the innovators themselves. In fact, Nordhaus concludes that only a “minuscule fraction”—about 2.2 percent—of the “social returns from technological advances over the 1948-2001 period was captured by producers, indicating that most of the benefits of technological change are passed on to consumers rather than captured by producers.” That means, as the Mercatus Center’s Don Boudreaux noted at the time, “that ‘society’ pays a paltry $2.20 for every $100 worth of welfare it enjoys from innovating activities.”

Subsequent studies of particular sectors and innovations—for example “Big Retail” or “Big Tech”—also reveal consumer benefits that likely dwarf the large profits earned by the companies’ founders and shareholders.

Given these studies (and plenty of others), there’s little reason to think that Pfizer, BioNTech, and Moderna are somehow earning windfall profits at the world’s expense.

In fact, given what the companies are producing and what their profits might generate in the future, we’re getting the bargain of the century.

Chart of the Week

Japan got old, and you’ll never guess what happened next (source):

Bonus Chart(s) of the Week

… while housing construction hasn’t kept up with household formation (link)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.