Dear Capitolisters,

You may have missed it over the holiday, but shortly before Christmas the White House declared total victory in its monthslong battle with global supply chains. After warning earlier in the fall that Christmas could very well be ruined, White House press secretary Jen Psaki called a press gaggle shortly before the big day and told the crowd, “Good news, we’ve saved Christmas.” She then added that the season’s lack of empty store shelves (rapid tests notwithstanding!) happened “because President Biden recognized this challenge early, acted as an honest broker to bring key stakeholders together, and focused on addressing practical problems across the global supply chain.” She even took to Twitter to rub it in (as one does):

Huzzah!

As you might imagine, the administration’s boasts were just a smidge exaggerated. Yes, the White House did recognize America’s ports and supply chain problems (how couldn’t they?) and did pursue a few quick fixes that probably lessened port and related supply chain pressures a bit, but the heavy lifting wasn’t done by anyone in D.C. It was done by private businesses and American consumers, in the process providing us with some important lessons about supply chains, market economies, and public policy more broadly.

What the White House Did

The White House created a supply chain task force and “Port Envoy” over the summer, but the administration’s biggest actions at U.S. ports—especially the critical Los Angeles/Long Beach hub—came in mid-September through early November. Key moves include: (1) getting LA/LB to commit to 24/7 operations through the peak season and encourage night/weekend pickups; (2) subsequently getting Walmart, UPS, FedEx, Samsung, Home Depot, Target, the Gap, and Stanley Black & Decker to commit to using more night shifts at the ports; (3) encouraging the LA/LB ports to assess “congestion fees” for long-dwelling containers that are clogging things up; (4) helping the Georgia Port Authority establish “pop up” yards for container overflow from the important Port of Savannah; and (5) temporarily relaxing U.S. trucking regulations to get more drivers on the roads.

What That Actually Achieved

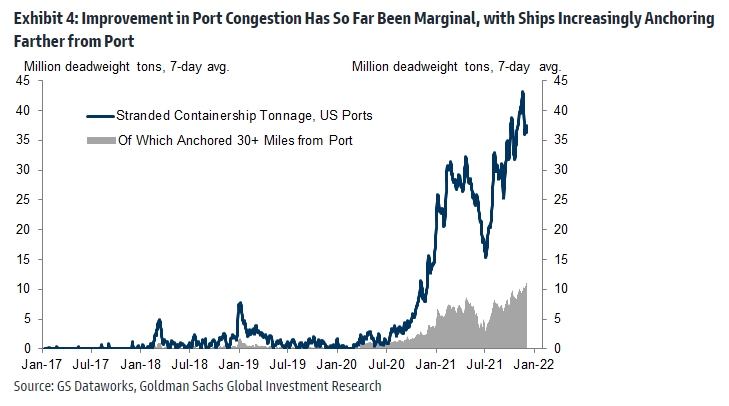

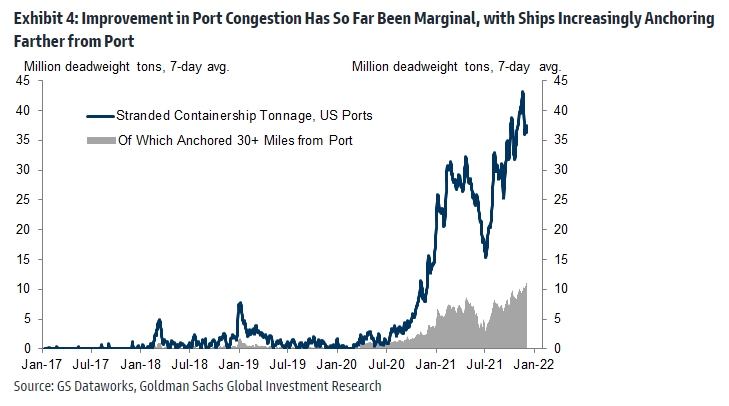

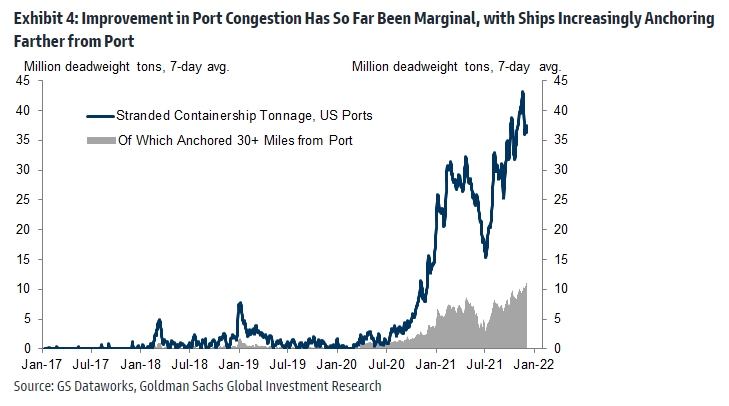

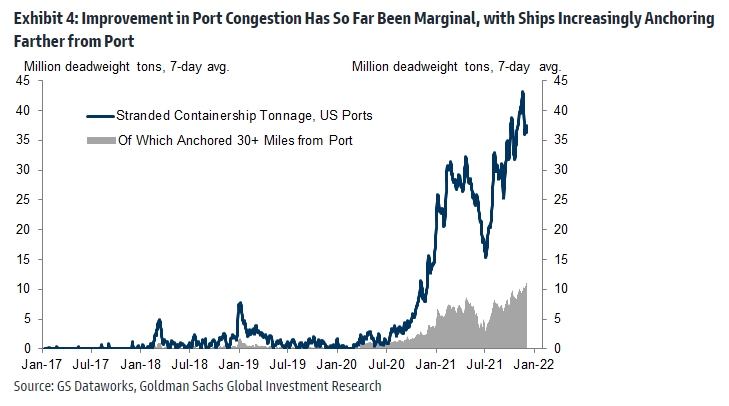

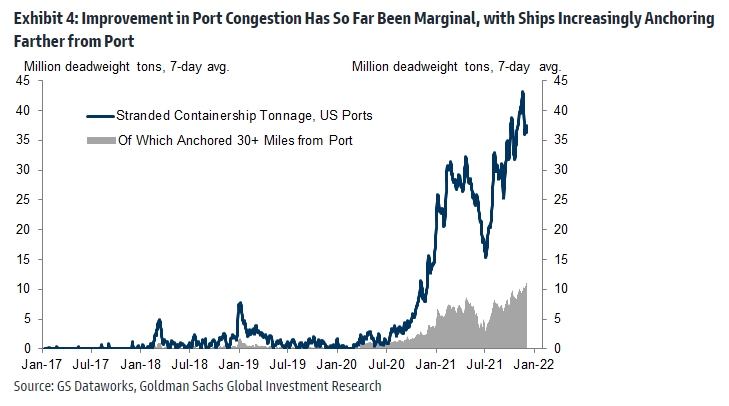

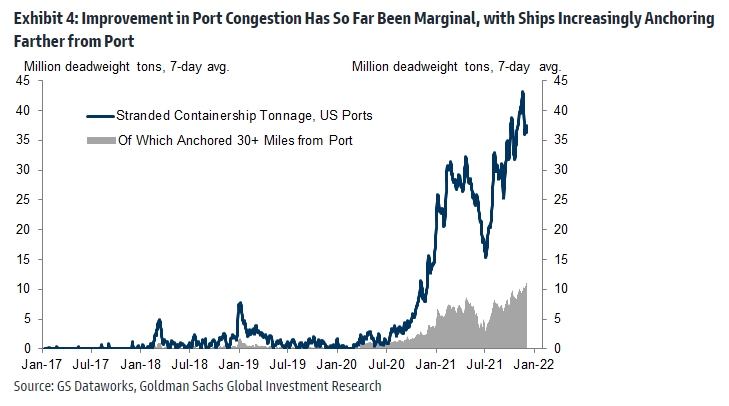

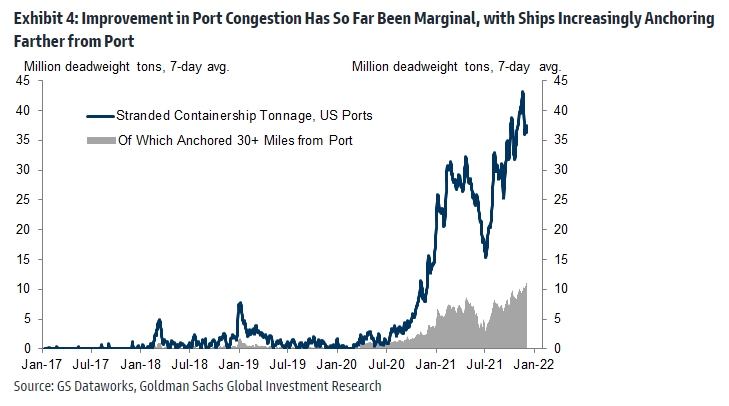

The White House certainly deserves some credit for recognizing America’s ports problems and trying to apply some quick, supply-side fixes. Contrary to the spin, however, the broader effects of these moves on store shelves and, by extension, Americans’ Christmas gifts, appear to be muted. For example, Goldman Sachs in mid-December found that, based on the actual level of container ship tonnage (not just ships) still stranded off U.S. shores, American port congestion had declined by only 3 percent over the last month and was still extremely (extremely) elevated:

A separate measure of just LA/LB’s productivity—how quickly ships get in and out of port (“berth moves”)—shows that things actually deteriorated further in the fall after a slight summer improvement:

In the fourth quarter of 2019, the average container ship dwell at berths in Los Angeles was three days, which reflects “normal” operations; by the fourth quarter of 2021, the average berth time had more than doubled to just shy of seven days, according to IHS Markit port performance data. Long Beach saw a similar uptick in vessel dwells, with ships berthed for an average of nearly five days in the fourth quarter of 2021, up from just under three days in 2019. Berth productivity has fallen as a result of the extended berth times.

The Journal of Commerce adds that this productivity decline has happened at all major U.S. ports, but “particularly on the West Coast” (i.e., where the Biden administration has focused its efforts). Indeed, Bloomberg reported just this week that while congestion at some East Coast ports has eased a bit, things are still really bad at the critical LA/LB corridor—despite some superficial data (e.g., on cleared empties) showing improvements:

Meanwhile, on the West Coast, there aren’t many visible signs of improvement despite the Biden administration’s intervention to unclog the pileup. The average wait for berth space for ships arriving into Los Angeles hit a record 23.4 days this week, up from 20.9 on Dec. 1, when President Joe Biden called for better coordination and faster movement of goods through the nation’s ports.

According to the Financial Times, the LA/LB bottleneck may be—given the port’s importance to the massive U.S. economy—the key to unlocking not just U.S. supply chains but ones around the world:

The size of the queue of vessels lined up outside the terminals has become a barometer of worldwide supply chain convulsions. While that queue has lengthened out many miles to sea because of new rules, the effective number of container ships waiting — above 100 last Thursday — is at a record high. LA/Long Beach accounted for roughly 22 per cent of shipping capacity waiting to berth globally last Tuesday, according to Kuehne + Nagel, a Swiss logistics group.

“If we solve North America, then there would be enough capacity for the rest of the system,” Alan Murphy, an analyst at consultancy Sea-Intelligence, told a meeting of shipping experts in December.

So while there are some initial signs that global supply chain pressures are abating (though still high) a bit, the U.S. port situation is far from fixed. And, as logistic firm Flexport’s Ryan Peterson stated last week, “At one point this October, there were over 500,000 shipping containers on ships waiting out at sea, with an estimated $30 – $50 billion worth of merchandise in them. Much of it did not get into warehouses and shops in time for the holiday shopping season.”

So maybe we hold off on spiking the (newly unwrapped) football?

So Who Did Save Christmas?!?

Yet despite this continued port and supply chain congestion, most Americans (myself included) experienced few serious disruptions this holiday season. The lion’s share of the credit goes, however, not to Washington but the market. In particular, thousands of U.S. companies and millions of American consumers adapted in all sorts of ways to ensure that the 2021 holiday season would work out just fine—even if a little different than past ones.

On the corporate side, large U.S. retailers recognized early on that the port and supply chain stresses already evident in 2020 would be amplified in 2021, so they moved up their shipments to ensure sufficient holiday inventories. For example, new data from the National Retail Federation’s Global Port Tracker show that retail imports surged in 2021 (almost 17.9 percent above 2020’s record high), but that the surge mostly came earlier in the year:

The chart above shows, in fact, that 2021 imports during the fall (i.e., when the Biden administration’s supply chain efforts could produce their alleged victory) were basically the same as those in 2020. The big moves came before they were ever really involved.

Retailers also moved to avoid the LA/LB morass altogether. As the Journal of Commerce noted, for example, “[u]p and down the East Coast, ports are seeing more vessels at anchor due to shippers diverting away from the congested Southern California gateway and the addition of new services.” The Port of Houston also experienced a surge in container imports last year (“seventh consecutive month of double-digit growth”), as big box retailers diverted shipments away from LA/LB.

These companies also did other things, like chartering their own container ships and planes, hiring more people, using different types of trucks and drivers, and diversifying warehousing and delivery options “to make sure the supply chain disruptions did not wreak havoc on holiday packages.” Amazon even started building its own shipping containers! And retailers are still adapting as we speak:

As a result of these early efforts, Amazon, Walmart, Target, Home Depot, and other large retailers reported (mostly) stocked shelves and/or record sales through November. Even some department stores, which have been declining for decades now, reported gains. Many—the ones that survived 2020, at least—now say that the pandemic was a hidden blessing, as it pushed them to reset antiquated, inefficient supply chain and inventory systems that were weighing on their businesses.

The big shipping companies, of course, did their part too:

The delivery companies have spent the past two years building out capacity… in response to surging demand. UPS, which in the past did not make deliveries on Saturday in much of the country, has been expanding its weekend service for years. It now offers Saturday deliveries to about 90 percent of the U.S. population. FedEx has added nearly 15 million square feet of sorting capacity to its network since June. And, starting in the spring, the Postal Service, which processes more mail and packages than the other delivery businesses, started leasing additional space and installing faster package-sorting machines around the country.

As a result, UPS, FedEx and even the Postal Service reported major (26 to 40 percent) improvement in the time it takes for a package ordered online to arrive at its U.S. destination, as compared to 2019 before the pandemic ever began.

Finally, consumers (i.e., you and me) adapted, too. Most notably, we moved up holiday purchases into the fall and even summer, instead of waiting until November or December—often at retailers’ urging (and to catch early sales). Bloomberg reported in November, for example, that fear of shipping delays and ever-increasing prices pushed many American Christmas shoppers to finish buying “before the holiday season even began.” Various retail surveys show the same, with significant percentages of Americans starting their shopping much earlier than last year and finishing before Thanksgiving.

The latest U.S. consumer data back these surveys and anecdotes up: Retail sales, for example, shot up in August through October thanks to early Christmas shopping but then moderated a bit in November, well below analysts’ expectations:

Consumer spending did basically the same thing: “Holiday shoppers snatched up gifts earlier than usual this year in anticipation of product shortages, helping to boost spending in October while contributing to a November sales slowdown.”

Consumers also did more shopping in stores, thus easing pressure on shipping companies. According to the New York Times, for example, “in-store shopping bounced back strongly this year, according to retail and logistics experts. In September, in-store sales accounted for about 64 percent of retail revenue, up 12 points from its low point during the pandemic.” And, of course, we just chose other presents when certain things were out of stock.

So nice work, everyone. Pat yourselves on the back.

Lessons Learned

Ok, so the White House didn’t actually save Christmas and instead store shelves remained (mostly) stocked due to the collective effort of millions of market actors around the world—especially the tireless work of large U.S. retailers and logistics pros determined to satisfy their customers’ seemingly insatiable demand for stuff this year (hooray, profit motive!). Political points aside, we can draw (at least) two big lessons from this episode:

First, despite their name, supply chains (and the market more broadly) aren’t some static, straight-line thing that just keeps taking its lumps when conditions change. Each one involves countless participants—producers, consumers, transporters, middlemen, etc.—constantly adapting to individual and broader market circumstances, often in ways that none of us expect. (Costco chartering giant container ships? Really?). It’s for this reason that George Mason University’s Don Boudreaux has been on a personal quest to rename the “supply chain” a “supply web”:

Instead of a collection of distinct supply chains, our modern economy is a single globe-spanning web of interconnectedness. Within this web every output is the product of countless inputs and each kind of input typically is used to produce countless different kinds of outputs. This web of interconnectedness—the complexity of which is beyond human comprehension—is indispensable for our modern mass prosperity.

A critical aspect of this “web,” Boudreaux adds, is economic change: “both change that is inseparable from a market economy’s creative destruction (for example, the invention of the assembly line), as well as change that is imposed on humanity by nature (for example, the depletion of an iron-ore mine). Such change at every moment rearranges—usually slightly, but sometimes dramatically—the particular connections that each node of the vast economic web has with innumerable other nodes.” As I’ve noted here repeatedly, this ever-adapting complexity—which has been so evident over the last two years of “supply chain crises” that keep magically getting resolved—is a key reason why “strategic” government economic planning (e.g., industrial policy) so often falls short: Even if our planners can resist omnipresent political temptations and figure out the supply chain/web, it’ll be different when they decide to “fix” it and different again when the bureaucracy finally acts on that decision.

And that brings us to the second big lesson here: Small, short-term fixes applied in the middle of a crisis rarely can resolve massive, complex, and systemic issues that have evolved over decades in response to all sorts of market and non-market factors. For example, it’d probably be great for U.S. ports and supply chains to move to 24/7 operations like those in many Asian countries, but there’s just no way that a few port terminals leaving out the Open Sign after 8 p.m. one day this fall was suddenly going to get thousands of truckers, importers, warehouses, and other players—whose schedules, contracts, and capacity were based on the previous arrangement—to hop to it at 8:01. Indeed, even the big U.S. retailers who agreed to utilize expanded night/weekend shifts at the ports could only boost throughput by about 14,000 containers per month—a mere 1 percent of the total container volume that LA/LB handled in August.

Real-world stuff like this is a big reason why the 24/7 move fell pretty flat: The whole, gigantic system was based on a slower, less efficient model and couldn’t just change overnight (literally!). Other Biden efforts—like those container fees—ran into similar problems, with disjointed rules made on the fly creating confusion among terminals, carriers, and retailers. One official went so far as to say that if the new rules were fully implemented (they’ve mostly been delayed), “the process would become so complex and time-consuming that it would actually exacerbate congestion woes.” Oops.

The supply web also reflects the various laws and regulations governing it—many of which have, as we’ve repeatedly discussed, inhibited adaptation and efficiency and thus contributed to the current mess. While reforming these sclerotic rules is worthwhile, doing so likely won’t solve the immediate crisis at hand. (You could repeal the Jones Act today, for example, but that move—while awesome for the country in the long term—wouldn’t suddenly fix the U.S. rail, trucking, and port system that the law has distorted for the last century.) In most cases, it’s just not like flipping a switch, regardless of the merits of reform.

In general, it’ll take time for manufacturers, ports, warehouses, ships, equipment, workers (and labor contracts), and other links in the supply chain (web!) to correct past mistakes and adjust to our “new normal” (e.g., Americans buying more goods via e-commerce). Policymakers certainly can and should help facilitate that adjustment—not by trying to predict the next crisis or pursue “strategic supply chain” whatever, but by reforming or repealing the numerous laws and regulations that intentionally diminish systemwide capacity and inhibit the market’s natural, perpetual adjustment.

We don’t need some politician to save us. We just need him to let us save ourselves.

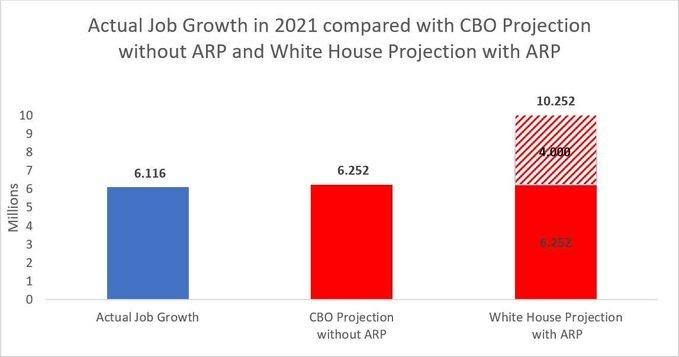

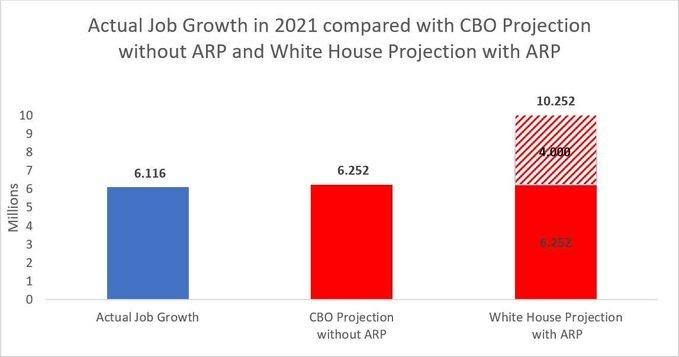

Chart of the Week

Bonus Chart of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.