Dear Capitolisters,

While things here at home are definitely looking up, the pandemic continues to rage elsewhere. Probably the worst situation, as you may have heard, is in India, where cases have exploded and deaths are likely being undercounted by severalfold. In response to these tragedies, people began calling on the United States—and particularly the Biden administration—to help alleviate the suffering by sending money and medical goods to India and other hard-hit places (many of which are also close U.S. allies). And, to its credit, the Biden administration has responded. However, questions remain about what the United States has done here, why we didn’t help sooner, and what we should do going forward. So that’s what we’ll discuss today.

The Situation in India

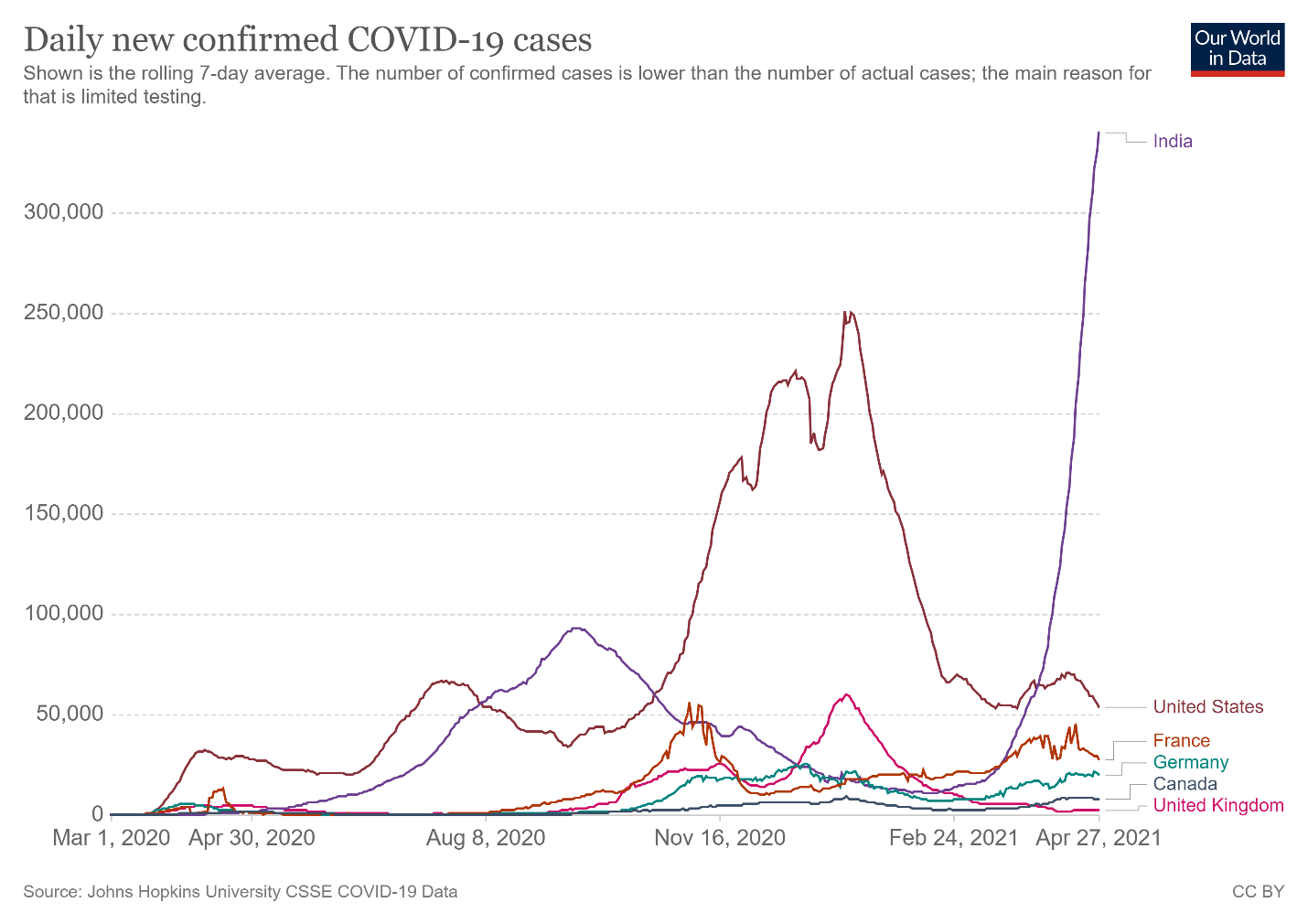

India is in dire straits. According to CNN, “[o]n Monday, India reported 352,991 new cases and 2,812 virus-related deaths, marking the world’s highest daily caseload for the fifth straight day.” Those figures have only moderated a tad since then:

Granted, as a share of population, India’s totals are actually lower than a few places in Europe and are just above the United States’ current case counts. The problems, however, are (1) India has a lot of people (almost 1.4 billion); and (2) the case counts there are very likely undercounted. For example, the New York Times recently reported that cremation activity portrays “an extensive pattern of deaths far exceeding the official figures,” as local politicians, hospital administrators, and grieving families have an incentive to undercount or not report cases. As University of Michigan epidemiologist Bhramar Mukherjee told the Times: “From all the modeling we’ve done, we believe the true number of deaths is two to five times what is being reported.” Other reports echo these (tragic) concerns.

India is getting the worst of it right now, but other countries—particularly in the developing world—are still struggling to contain the virus and probably will be for months (if not longer). All of this raises the obvious question: What, if anything, should the United States do about it?

The Situation Here

Before we get to that, however, it’s necessary to understand the pandemic-related policies that the United States currently has in place for various types of medical goods, and the current status of those goods in the U.S. market. There’s a bit of a “fog of war” problem in figuring all of this out (more on that in a sec), but there are two main things at play here: formal and implicit export controls and various contract restrictions, almost all of which are tied to the Defense Production Act (DPA). As I explained in a Cato Institute blog post on Monday, Presidents Trump and Biden have repeatedly invoked the Cold War-era DPA, “which confers upon the executive branch broad powers to compel (Title I) or subsidize (Title III) private actors in the United States on ‘national security’ grounds, in order to expand the domestic production and distribution of essential medical goods like N95 masks and vaccines.” For today’s purposes, most of the action has occurred under DPA Title I.

Vaccines and vaccine materials. Relying on Title I, the U.S. government has required domestic producers of vaccines and related production inputs to (1) acceptU.S. government contracts for these materials and prioritize delivery before anyone else, or (2) perform a contract with another private party (e.g., a vaccine producer) to fulfill its priority government contract. Thus, for example, if the feds need vaccines, they can invoke DPA Title I to (1) compel Pfizer accept and prioritize a government contract before servicing any other buyers; or (2) compel Pfizer’s domestic suppliers, who have contracts with Pfizer and others, to service Pfizer first.

It’s not entirely clear how the DPA has been invoked here because the law doesn’t mandate transparency (a big problem in itself, as I explained on Monday), but we know from various public reports—and the White House itself—that the government has used the law to “prioritize” domestic supply of vaccines and vaccine materials. With respect to the former, the U.S. government has contracts with several vaccine manufacturers for the domestic supply of a set number of vaccines, at least two of which—AstraZeneca and Moderna—have language expressly invoking DPA Title I authorities by setting a “priority rating” for the contract. (Moderna’s was amended to add this rating.) There has been a lot of other DPA talk surrounding the vaccines—including a quite public Pfizer-Trump administration kerfuffle last December over contracted and additional doses—so it’s possible that other DPA-related amendments are out there. Regardless, such terms probably don’t matter too much, given that the Biden administration could simply invoke the DPA to force vaccine makers to satisfy their U.S. government contracts. (Then-HHS Secretary Alex Azar repeatedly threatened to do this with Pfizer before they came to a deal in late December.)

The contracts also contain language prohibiting the U.S. government from sending finished vaccine doses abroad (to maintain producers’ liability under the PREP Act), but—as I noted on Twitter the other day—there’s little reason to think that these terms couldn’t be modified, or that the U.S. government couldn’t simply breach the deal and pay damages, if needed. So this excuse is a red herring.

The DPA situation regarding vaccine materials is a little clearer: Both the Biden and Trump administration have invoked the DPA to assign “priority ratings” to U.S. suppliers’ contracts with Pfizer, Moderna, and other vaccine manufacturers. The Washington Post, for example, notes that “giving Pfizer priority for a number of crucial products—such as lipids, the oily molecules needed to produce the vaccine—was among the terms of a deal for additional doses reached by the Trump administration in December.” The Biden administration expanded that deal in February, and, because the U.S. is a major global producer of vaccine inputs, all of these DPA actions have become a big issue in India (emphasis mine):

On April 16th Adar Poonawalla, head of the world’s biggest vaccine-maker, the Serum Institute of India (SII), begged President Joe Biden, in a tweet, to “lift the embargo of raw material exports out of the us…Your administration has the details”. Suresh Jadhav, SII’s executive director, says that in the next four to six weeks manufacturing of two vaccines will be affected: AstraZeneca’s, of which SII makes 100m doses a month, and Novavax’s, of which it expects to make 60m-70m doses a month. SII says it first alerted the American government about this two months ago.

That was shortly after the Biden administration announced, on February 5th, plans to use the Defence Production Act (DPA)—a law dating from the 1950s that grants the president broad industrial-mobilisation powers—to bolster vaccine-making. This legislation, previously invoked for similar reasons by Donald Trump when he was president, has helped American pharmaceutical companies to secure a variety of special materials and equipment, including plastic tubing, raw goods, filters and even paper, that are needed for vaccine production. But firms which export such products point out that the DPA hinders their ability to sell them abroad. They must seek permission before exporting these goods. That requires time and paperwork. And if the government decides it needs the goods in question to remain in the country, the firms concerned may be barred from exporting them at all. Some people are also worried about pharma companies outside America stockpiling goods because of concerns about delays caused by American export controls. Together, export controls and stockpiling risk gumming up the global supply chain.

As is well-known by now (at least around here!), the United States is sitting on millions of finished AstraZeneca doses that have been approved in several countries but are still not approved for use domestically, and the federal government has contracted for millions of other doses—such as those made by Novavax—that we might never need, given expanded contracts with Pfizer and Moderna. As Bloomberg reports, these expanded supplies—combined with some demand-side issues here (vaccine-hesitancy, hard-to-reach citizens, etc.)—means that we have an increasing number of jabs just sitting around:

The U.S. is now reasonably assured of having enough vaccine. It has contracted for 600 million shots from Pfizer Inc. and Moderna Inc., and the drugmakers are delivering those doses faster than they are being used. About 28 million shots are being shipped a week, and 21 million are being used.

Johnson & Johnson’s one-dose vaccine, which was on a brief safety hold after concerns about rare blood clots, is likely to end up an also-ran in the U.S. Given how much Pfizer and Moderna is being shipped versus how much is being consumed, J&J’s shot may end up as a comparatively niche product, or be used mostly abroad, or reworked as a booster shot.

There are just under 10 million J&J doses that have been delivered but are still unused, according to CDC data. At the current rates of delivery and use of Moderna’s and Pfizer’s shots, about 7 million doses a week of those vaccines are building up, as well.

Politico reports this morning, moreover, that White House officials are also well aware of this growing surplus and have been for weeks: “An individual familiar with the Biden team’s supply projections said the U.S. has known for weeks that it would have enough vaccine doses for all U.S. adults by the end of May, even without J&J. The U.S. will receive 450 million doses by the end of May and will have another 100 million additional doses manufactured and waiting for testing …”

As Bloomberg notes, having tens of millions of doses “sitting on shelves” and waiting for willing American arms is an inevitable part of the vaccination effort here. But there is no need for too much of this luxury as humanitarian crises unfold elsewhere—something that public health officials, including those in the Biden administration, all seem to understand. As Krishna Udayakumar, director of Duke’s Global Health Innovation Center, told Politico, “There’s no reason for the U.S. to sit on doses and have hundreds of millions of doses on the shelf over the summer. If and when more doses are needed in the fall and into the winter, the manufacturing capacity is going to ramp up pretty significantly.”

Medical goods. Last year, President Trump issued a memorandum, “Allocating Certain Scarce or Threatened Health and Medical Resources to Domestic Use,” which used DPA Title I “allocation authority” to direct FEMA to effectively ban the exportation of various medical goods by requiring that they be “allocated for domestic use,” unless explicitly exempted by the agency. Last December, FEMA extended the export restriction through June 30, 2021 and clarified that it covers the following items:

-

Surgical N95 respirators;

-

Surgical masks, specifically PPE surgical masks that meet industry standards;

-

Nitrile gloves and exam gloves;

-

Surgical gowns and surgical isolation gowns; and

-

Syringes and hypodermic needles.

In January, FEMA issued additional guidance on these rules and possible exceptions, two of which are (1) shipments by or on behalf of the U.S. federal government, including its military; and (2) exporters who “have a surplus of a covered material and can demonstrate a good-faith and unsuccessful attempt to sell the material domestically.” FEMA reportedly invoked the second exception to allow Texas-based Prestige Ameritech to export millions of N95 masks late last year. As far as I know (after extensive Googling and a search of the Federal Register), this export ban remains in place today.

Since FEMA’s guidance was issued, of course, the pandemic here has waned significantly, and the PPE situation has further improved because of both increased production and declining consumption. As I noted a few weeks ago, for example, the U.S. International Trade Commission reported in December that domestic production of many medical goods had expanded during the pandemic, and supplies were in pretty good shape. Several members of Congress even went so far as to complain about a potential glut of U.S.-made PPE. Now, the AP reports with respect to N95s that “U.S. manufacturers say they have vast surpluses for sale, and hospitals say they have three to 12 month stockpiles.” Prestige Ameritech’s VP added that his company “has millions of unsold masks, as do other U.S. manufacturers which invested and ramped up during the pandemic.”

In short, we have plenty of PPE to spare (outside of maybe rubber gloves).

The Biden Administration’s Recent Actions

Given the situation and mounting public criticism, the Biden administration announced several efforts to help India cope with the pandemic. On Sunday, for example, the White House announced that:

The United States has identified sources of specific raw material urgently required for Indian manufacture of the Covishield vaccine that will immediately be made available for India. To help treat COVID-19 patients and protect front-line health workers in India, the United States has identified supplies of therapeutics, rapid diagnostic test kits, ventilators, and Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) that will immediately be made available for India. The United States also is pursuing options to provide oxygen generation and related supplies on an urgent basis. The U.S. Development Finance Corporation (DFC) is funding a substantial expansion of manufacturing capability for BioE, the vaccine manufacturer in India, enabling BioE to ramp up to produce at least 1 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines by the end of 2022.

It’s still not entirely clear how most of these actions are being implemented, but Tim Manning, White House COVID-19 supply coordinator, took to Twitter on Monday to explain how they’ve used the DPA and what they’re doing regarding one specific vaccine input:

The White House also approved the release of millions of unapproved AstraZeneca vaccine doses that same day, building on similar promises that the administration made to Japan, Canada, and Mexico a few weeks ago.

The Biden administration’s actions are laudable, but they also shouldn’t be oversold: First, any shipments of vaccine materials—even if sent Sunday—couldn’t possibly translate to finished doses in the immediate term, though they will be useful down the road. Same goes for the DFC financing. Second, press secretary Jen Psaki subsequently poured cold water on how quickly the finished AstraZeneca doses might be shipped to India:

[She] cautioned at a news conference that the donations of doses would not happen right away. She said about 10 million doses could be released “in the coming weeks” if the F.D.A. determines that the vaccine meets “our own bar and our own guidelines,” and that another 50 million doses are in various stages of production.

“Right now we have zero doses available of AstraZeneca,” Ms. Psaki said.

In a statement, a spokesperson for AstraZeneca said that the company would not comment on specifics but that “the doses are part of AstraZeneca’s supply commitments to the U.S. government. Decisions to send U.S. supply to other countries are made by the U.S. government.”

The Financial Times adds that the FDA review “would have been far shorter had it not been for manufacturing problems at the Baltimore plant owned by Emergent BioSolutions, where a mix-up of vaccine ingredients last month ruined doses of the AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson shots.” Normally, “quality control checks for Covid-19 vaccines usually only take a matter of days and are performed throughout the manufacturing operations.” At some point, we’re really going to need a full autopsy on the (problematic and instructive) Emergent situation, but for now we can just say “ugh.”

It also could take weeks, of course, for these vaccines to take effect once administered. Thus, only the PPE, testing equipment, and oxygen might make an impact in India in the coming days, but we don’t yet know the quantities involved. Let’s hope they’re significant.

What More Should Be Done

Given the unfortunate practical realities involved here, I just don’t know how much U.S. aid will help India in the near term, and it’s a real shame that these efforts weren’t initiated weeks ago when folks were first starting to ring alarm bells. Indeed, the aforementioned Politico report notes that White House officials have long been aware of both the U.S. vaccine surplus and the growing international need, yet didn’t act sooner because of, at least in part, “the optics of sending doses abroad during a big push to make vaccines more available to U.S. citizens.” The State Department repeated this line last week when asked about India and the export restrictions, trying to punt the issue to USTR (which makes little sense) and then citing their “special responsibility to the American people.” It was only when the humanitarian crisis became unavoidable (and maybe when China offered to help?) that the White House decided to act, losing precious time (and more) in the process.

This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t help, of course; it just means we should be clear-headed about the potential effects. (I obviously hope I’m wrong.) It also means the United States should be far more proactive about heading off “future Indias” now, instead of waiting for them to explode and public outcry to reach a fever pitch. The DFC funding could help this regard (for more on expanding global vaccine production capacity, see the links here), as could the following actions:

-

Immediately lifting FEMA’s export restrictions on all medical goods, which are today unnecessary and might—as export restrictions often do—actually discourage U.S. production as manufacturers struggle to find domestic buyers. These hurdles are surmountable, and the U.S. will probably never be a massive global supplier of low-cost PPE, but the restrictions slow things down and every little bit helps.

-

Shelving the DPA for vaccine materials and finished doses. Contrary to Manning’s claims on Twitter, a requirement that U.S. companies prioritize domestic demand does act as a “de facto” export restriction on vaccine inputs, as long as global demand far exceeds supply—a situation that’s definitely still the case here. (Such “must sell” measures are a classic international trade issue.) As The Economist noted above, restrictions on U.S. exports “gum up global supply chains” and encourage hoarding in other countries, and—as noted—might also discourage domestic producers of inputs and finished doses from making more or investing in new U.S. capacity. American vaccine producers have already proven able to refine their manufacturing processes to improve output, and eliminating the DPA threat (or express contract terms) could encourage them to do even more.

-

Allow AstraZeneca vaccine recipients to decide whether they want all that additional FDA scrutiny of the doses or simply value speed even more. As already noted, AZ itself has punted to the United States about what to do with these doses, and Canada just recently vouched for the safety of doses made at Emergent’s Baltimore facility. Maybe India (which has already approved the AZ vaccine and just granted emergency approval of any vaccine approved by stringent regulators elsewhere) and other countries are willing to wait for the FDA, but maybe they’re not—we should let them decide.

-

Come to an arrangement for mRNA technology transfer (if needed). As The Economistnotes, “liberating vaccine [intellectual property] would not unleash a flood of new production” because the biggest obstacles to expanding capacity are supply constraints and “proprietary resources and other know-how, which are not shielded by patents.” Indeed, many countries face no patent barriers to using Pfizer and Moderna’s mRNA technologies. Vaccine producers have already entered into numerous partnerships around the world, but—to the extent more is necessary—the easiest solution is to simply pay these companies to license and help implement their technologies for production elsewhere.

With the pandemic generally under control here and tens of millions of unused vaccine doses already floating around our system, none of these actions is likely to harm the U.S. response to COVID-19 or materially harm our daily lives. By contrast, these efforts could provide significant benefits, beyond the obvious humanitarian ones in India and other struggling regions. As George Mason University’s Alex Tabarrok recently told Congress, for example, vaccinating most of the world (3 billion vaccine courses) is estimated to generate $17.4 trillion in global output, much of which would—like it or not—benefit the U.S. economy too (“even after the U.S. and other high-income countries are vaccinated the U.S. will continue to bear economic costs due to reduced exports, imports and supply-chain disruptions so there are pure economic reasons to vaccinate the world”). Ending the pandemic abroad also makes things safer here at home: “The unvaccinated are the biggest risk for generating mutations and new variants. You have heard of the South Africa and Brazilian variants, well the best way to protect your constituents from these and other variants is to vaccinate South Africans and Brazilians.” Finally, very public U.S. efforts to help the world fight COVID-19 would also reap geopolitical benefits, countering early (and not-so-effective) efforts from China and Russia to gain influence via “vaccine diplomacy.”

It’s a total no-brainer. What are we waiting for?

Charts of The Week

Bonus Chart of The Week

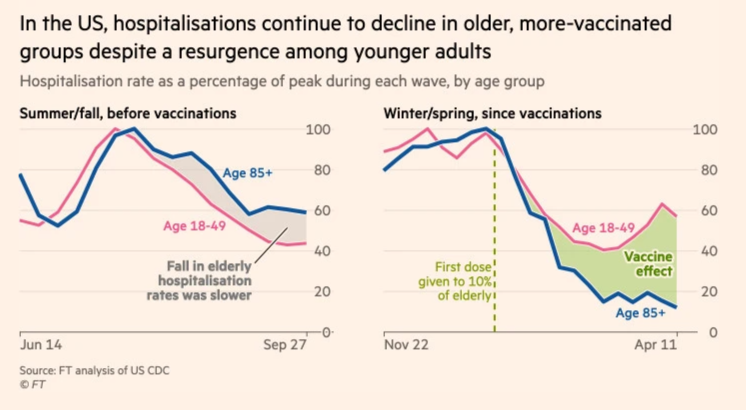

Vaccines are working. (Source)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.