One of the reasons stock markets rejoiced when President Donald Trump announced a 90-day pause of his now-infamous “reciprocal” tariffs was the belief (hope?) that the messy episode might result in not only those tariffs never being imposed but also new and important agreements with now-closed countries around the world. Foreign governments were lining up, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent told us, to sign deals with the United States that would give U.S. businesses expanded access to their markets and allow participating nations to collectively pressure China into reforming its troublesome economic policies. And Trump’s negotiators were getting to work immediately on inking those deals in rapid succession.

In some sense, Mr. Market had a point: Given the reciprocal tariffs’ origins and effects, literally anything was better than the dumpster fire we were promised on “Liberation Day,” and many markets abroad really do need opening (though this has been greatly exaggerated). Getting fewer tariffs and a bunch of deals over the next few months would thus be a big win over the expected status quo. So, stocks went up.

Unfortunately, this optimistic scenario faces some very real challenges—ones that likely limit both the number and quality of U.S. trade agreements we’ll eventually get (though we’ll almost certainly get something). Even worse, however, is that even better deals could’ve been achieved without ever firing a tariff shot (and thus enduring the related economic pain that even Trump himself acknowledges)—deals with many of the same nations that the Trump administration is now prioritizing.

Reasons for Skepticism

Immediately following the big pause announced on April 9, Bessent and other Trump administration officials were quick to promise a conga line of bilateral trade deals that would be signed before the taxes kicked in again in early July. White House trade adviser Peter Navarro even went so far as to promise that he, Bessent, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, and Trade Representative Jamieson Greer would defy the globalist skeptics and “run 90 deals in 90 days.”

The skeptics, alas, have several pesky facts in their corner.

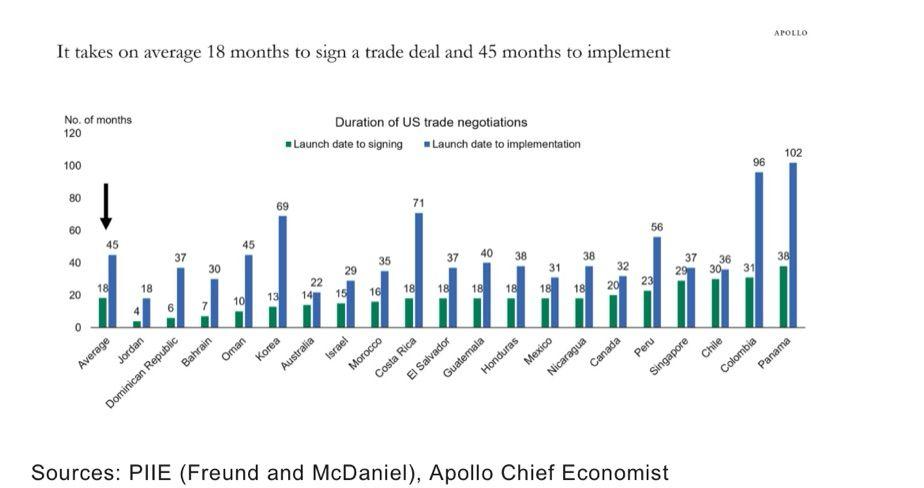

First, there’s the simple matter of the time and resources needed to complete a substantive trade agreement. As former U.S. trade negotiator Wendy Cutler recently explained, “[t]ypically, U.S. officials spend at least six months—twice the length of time of the current pause—just to develop their negotiating positions in consultation with Congress and stakeholders” (business, labor, etc.). Once concrete trade objectives are established, she adds, the “actual negotiations usually span several years” as U.S. and foreign government negotiators make offers and counteroffers in a series of in-person talks, run draft terms by their bosses and private stakeholders at home, and slowly close out individual chapters once those terms are agreed. After a U.S. trade agreement is finalized and signed, moreover, it needs to be approved by Congress (which has constitutional authority over trade policy) and, per previous versions of the “Trade Promotion Authority” law formalizing the process for negotiating and approving trade agreements, subject to an economic analysis by the U.S. International Trade Commission. These can also be lengthy processes involving multiple hurdles and potential delays.

For these reasons, it can take years to sign and implement a single U.S. trade agreement, which at that point will have been negotiated and scrutinized by dozens of federal government officials and analysts across numerous government departments, not to mention various outside business, labor, economics, and civil society groups. Even the fastest U.S. free trade agreement (FTA)—with tiny Jordan—took longer to sign than the 90 days Trump’s team now has. Given that USTR’s staff is only a couple hundred people total, and that Trump insists on negotiating bilaterally (one-on-one), doing dozens of these trade deals before July would be nothing short of impossible.

Ignoring past process and doing stuff on “Trump time” won’t make these obstacles magically go away. As Reuters notes, for example, “Even the smallest of Trump’s first-term trade deals, revising the automotive and steel provisions of the U.S.-South Korea Free Trade Agreement, took over eight months while the comprehensive U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement on trade took more than two years.” It’s thus unsurprising to hear that the administration is reportedly looking to publish only vague “term sheets” outlining core commitments and eventual deliverables instead of final, signed agreements, and that it’s prioritizing deals with certain Asian countries—Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Cambodia, South Korea, etc.—to “isolate China” and push Beijing to back down from the current trade hostilities and negotiate its own deal with the United States.

Even this slimmed down approach, however, will face real challenges because there are other hurdles to concluding deals quickly that have little to do with resources or trade policy. In developed countries, for example, most tariffs have been eliminated—hence, why average tariffs are low in the EU and elsewhere—and the remaining ones are highly political (and thus hard for politicians to remove). In developing countries, meanwhile, tariffs are higher but—along with similar trade politics as in developed countries—are needed for revenue. Because these countries typically lack the resources for nontariff barriers like subsidies and regulatory restrictions, moreover, powerful domestic industries—farmers, manufacturers, workers, etc.—will fight like crazy to keep tariffs in place.

Furthermore, many alleged nontariff barriers Trump is targeting aren’t actually trade barriers at all or, in the case of domestic tax and regulatory policy, are considered sovereign domestic (not trade) policies or cultural priorities not up for negotiation—at least not quickly. Other “cheating” is, like “dumping” and intellectual property theft, overblown (at best) and already disciplined by U.S. law. And, of course, the U.S. government does a lot of this stuff too (see, e.g., our trillions in subsidies)—often more so than other governments. Throw in the simple fact that basic politics makes it hard for democratically elected foreign leaders to be seen as caving to a guy like Donald Trump, and it’s not gonna be an easy slog.

Next, there’s the small matter of what the United States actually wants in these deals. Foreign diplomats tell Cutler, for example, that they lack clarity about the White House’s priorities—a necessity for focusing negotiators’ efforts during highly accelerated talks. Others report similar concerns from both the European and Japanese teams as to the U.S. demands and objectives. Is it tariff cuts, nixing nontariff barriers, reducing trade deficits, guaranteeing purchases of U.S. goods, countering China, or something else? And is the U.S. side willing to give on anything, including its own trade barriers, reducing “reciprocal” tariffs below the 10 percent universal rate, or new exclusions like the one Trump quietly announced for consumer electronics?

Even Trump backers are asking these questions; nobody seems to know the answer, and in the meantime the clock is ticking.

This problem may stem from the fact that, even inside the White House, there appear to be conflicting objectives. Politico reports, for example, that Trump’s advisers and allies are torn between striking major deals that would lower U.S. tariffs for key trading partners and keeping those tariffs in place to juice government revenue and protect domestic manufacturers. The Wall Street Journal adds that there’s a growing rift between protectionist Trump-whisperer Navarro and the more moderate Bessent/Lutnick duo, the latter of whom convinced Trump to implement “the pause” and start up these deals when the former had momentarily stepped away from the Oval Office. (Laugh or cry—your pick.)

Finally, there are the incentives acting strongly against cutting a big, beautiful trade deal with a U.S. president that has repeatedly ignored past intergovernmental agreements—including ones Trump himself signed. His fentanyl tariffs ignored his own USMCA with Canada and Mexico; his updated steel and aluminum tariffs blew up past deals with those two countries, as well as Argentina, Australia, Brazil, the EU, Japan, South Korea, Ukraine, and the U.K.; and his reciprocal tariffs ignore U.S. commitments under the World Trade Organization agreements and—except for USMCA—all past U.S. trade agreements, including the mini-deals Trump negotiated with Japan and Korea last time around. Cutler notes similar frustrations: “In my recent conversations, foreign trade negotiators have expressed exasperation about making major announcements of U.S. investments or purchases without receiving any credit for these actions in the tariff rates assigned to their countries.” Thus, she expects negotiators to drive a hard bargain and hold out until “everything is agreed”—something that appears to now be happening with top trade deal target Japan.

Even when things are agreed, however, it’s difficult to believe that negotiators will be willing to give the U.S. their best and final offer: Why would you spend a massive amount of political capital today to sign a trade deal that Trump might just rip up tomorrow?

And this assumes, of course, that Trump even wants to make serious trade deals, as opposed to just an excuse for keeping his beloved tariffs in place if/when talks fail.

Traditional ‘Reciprocity’ Has Worked

All this being said, I nevertheless expect some deals to get done in the coming weeks—probably even a few with decent wins for the Trump administration (and all, of course, announced with great fanfare as to the brilliance of Trump’s approach). The incentives—for Trump the dealmaker, his negotiating team, certain foreign governments dependent on the U.S. market or security umbrella, and various businesses—are just too strong for it all to blow up. (I think.)

Before we go popping Champagne, however, it’s important to ask not just what we got but what else the United States could have done to achieve these wins and much more. And here’s where things get really depressing, because what Trump abandoned to generate his big wins will likely have been far better than what he’s now putting in place.

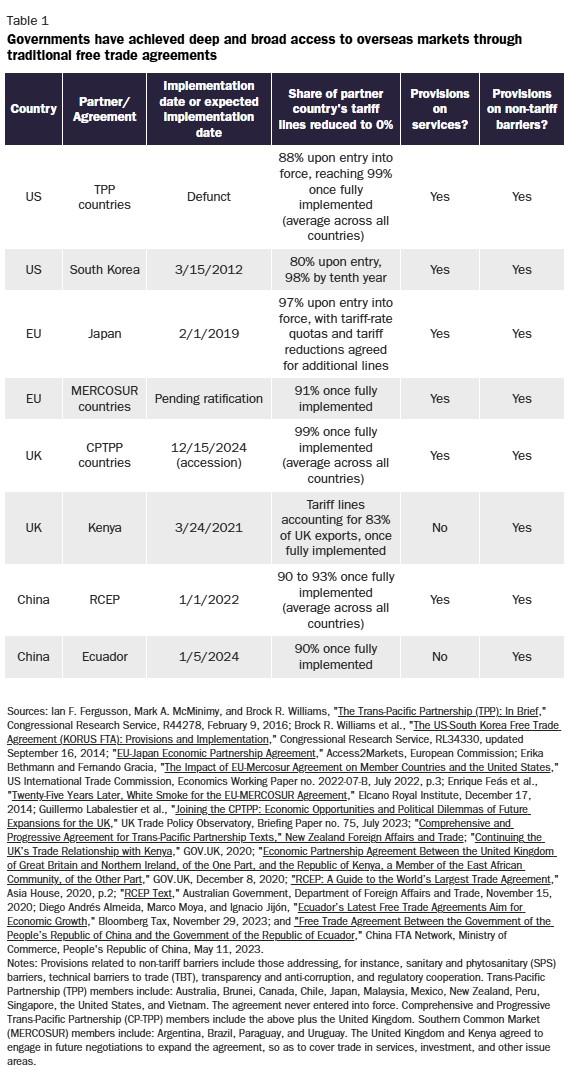

That discarded model—centered on a different kind of “reciprocity” and a different kind of trade agreement—was often slow and imperfect but still rather successful in achieving what Trump says he’s trying to achieve in the current negotiations: eliminating foreign barriers to U.S. goods and services, and increasing U.S. exports. Under the old approach, a government would agree to lower most of its trade barriers in exchange for another government doing the same, with both seeking an overall balance of concessions—not a line-by-line mirror image—to allow for different carveouts that reflect each nation’s political sensitivities. Following extensive negotiations involving multiple domestic stakeholders (business, labor, legislatures, etc.), the governments lock in their new market access terms via a comprehensive “free trade agreement.” The United States today has 14 of these bilateral and regional deals with 20 different countries, and each eliminates not only the vast majority of partner countries’ tariffs (typically more than 98 percent) but also many nontariff barriers to U.S. goods, services, and investment. They also provide a forum for governments to peacefully resolve disputes about how the agreements are being implemented.

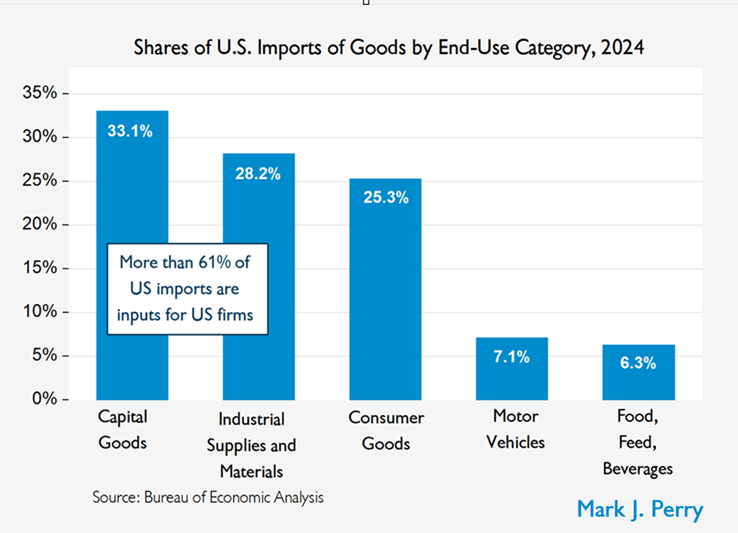

Free traders like me have long groused about FTAs’ details, especially as compared to idealistic alternatives like unilateral liberalization, but the agreements have generally worked to boost trade and the U.S. economy. As a result of these deals, for example, U.S. exports to FTA partner countries have increased faster than U.S. exports to the rest of the world, and by 2023, 47 percent of U.S. goods exports went to places that committed in a trade agreement to accept American goods and services duty-free. Domestic companies and consumers, meanwhile, benefited from improved access to imports from these same places, thus supporting American jobs and living standards. And both U.S. and foreign investors gained from the certainty that—unlike the shambolic executive actions Trump has enacted—is provided by a permanent trade agreement hardwired into domestic law.

These trade agreements are often oversold by critics and supporters alike, but rigorous studies have repeatedly shown that agreements like NAFTA and the U.S.-South Korea FTA have generated small but significant improvements in the U.S. economy, boosting gross domestic product, manufacturing output, inflation-adjusted wages, and total employment for both college-educated workers and those with only a high school degree. And, of course, the gains were achieved without new and costly tariffs and trade wars—one reason, as we discussed in January, why other governments aren’t abandoning them, including ones with which the Trump administration is now negotiating. As of today, there are hundreds of these FTAs in place around the world; it’s only the United States that has decided to ditch the model entirely.

Ah, What Could Have Been

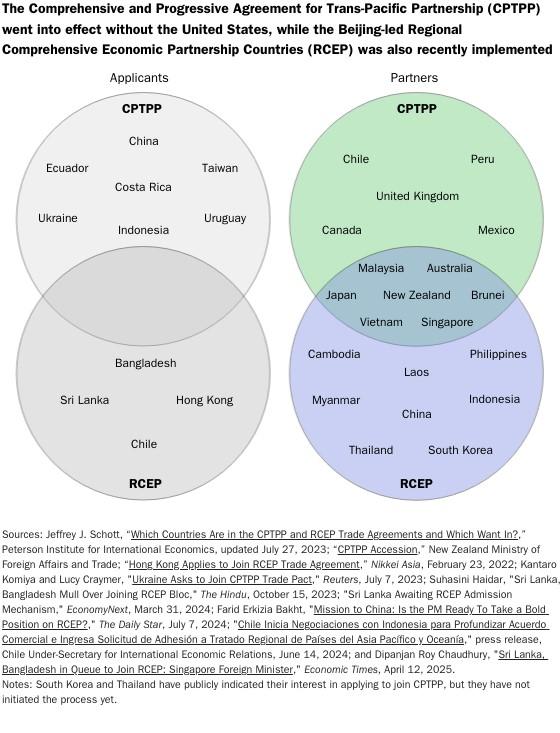

Indeed, the sad irony of our current tariff mess is that several of the most prominent targets of Trump’s tariffs and potential future trade deals—Japan (facing a 24 percent reciprocal tariff), Vietnam (46 percent), Malaysia (24 percent), Taiwan (32 percent), Indonesia (32 percent), the U.K. (10 percent), and more—are currently members of or applicants to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). That deal, you may recall, used to be known as the Trans-Pacific Partnership before Trump abandoned it on his first day in office in 2017 after a year of railing against it on the campaign trail. (Click the link to read my previous deep dive into the agreement.) The TPP was specifically intended to boost U.S. ties with AsiaPac nations in China’s economic and geopolitical orbit by reducing the bulk of member countries’ barriers to other TPP parties’ exports and investment. Thus, as my Cato Institute colleague Colin Grabow just depressingly documented, if Trump had simply stayed in the TPP, almost all tariffs on U.S. exports to Japan, Malaysia, Vietnam, the U.K. and other member countries would today be at or rapidly approaching zero. Other barriers to American goods, services, digital trade, and investment would have been eliminated too, and American companies and consumers would be enjoying better access to TPP members’ stuff, too.

Other FTAs, Grabow shows, have achieved similar (though admittedly often less ambitious) levels of new market access for their participants—including ones involving Europe and China, two of Trump’s other big trade targets:

The TPP/CPTPP also has other procedural benefits on which we’re now missing out. As a regional deal with many members, it saves negotiators’ time and energy by settling on a core set of terms that don’t need to be negotiated on a country-by-country basis, letting them focus on key bilateral irritants. Because the agreement balances concessions among all parties, compliance is more likely and enforcement is far easier than one-sided agreements like Trump’s now-imploded “Phase One” deal with China. The TPP/CPTPP also includes a mechanism for member countries to admit new parties to the agreement after the acceding government commits to opening its market, implementing the deal’s core provisions, and addressing current CPTPP members’ specific trade concerns. That’s precisely how the U.K. became a new CPTPP member last December, and it’s a process that the U.S. could have leveraged to access new markets abroad and eliminate specific barriers to U.S. exports and investment—just what Trump’s “reciprocal” tariffs are supposed to be doing right now.

These processes could have come in handy today, given Trump’s desire to enact deals quickly and how many Asian countries, as well as other top Trump targets like Cambodia (49 percent), are members of the China-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which has achieved significant—though not as good as CPTPP—liberalization and interconnectivity among its member countries:

Today, instead, we get none of these benefits and face not only severe economic turmoil at home and abroad (see links at bottom) but a ticking-time-bomb setup that—as even Trump backers acknowledge—might actually be undermining U.S. negotiating leverage because “panicked” markets are practically demanding some quick trade deal wins. Meanwhile, China is busy cozying up to many of the Asian countries with which it already has a trade deal and several others more firmly in the United States’ orbit. (Or, at least, they were.) Lest you think only China is doing such things, please note that liberal democracies are looking to work around the U.S. too—perhaps even with the CPTPP at the center:

As I wrote in 2022, Trump’s abandonment of the TPP—and Joe Biden’s refusal to take it back up in 2021—were colossal policy mistakes. They’re even more colossal in retrospect today.

Summing It All Up

Despite practical, policy, and political hurdles that make quickly negotiating dozens of bilateral trade agreements all but impossible, we should expect something to get inked between now and July—maybe even something soon. But getting a “deal” is the easiest part of the trade game; what matters far more is what, exactly, we’re getting; whether countries actually follow through on their commitments; and how it all compares to a realistically available alternative. In this case, it’s highly likely that whatever trade deals we get won’t be worth the economic pain we’re now facing and will pale in comparison to the slow, imperfect approach embodied in deals like the TPP—ones that Trump and other “post-neoliberal” types in the U.S. have mindlessly abandoned, and that promise to keep putting the United States—and American companies, workers, and consumers—at a serious, long-term trade disadvantage.

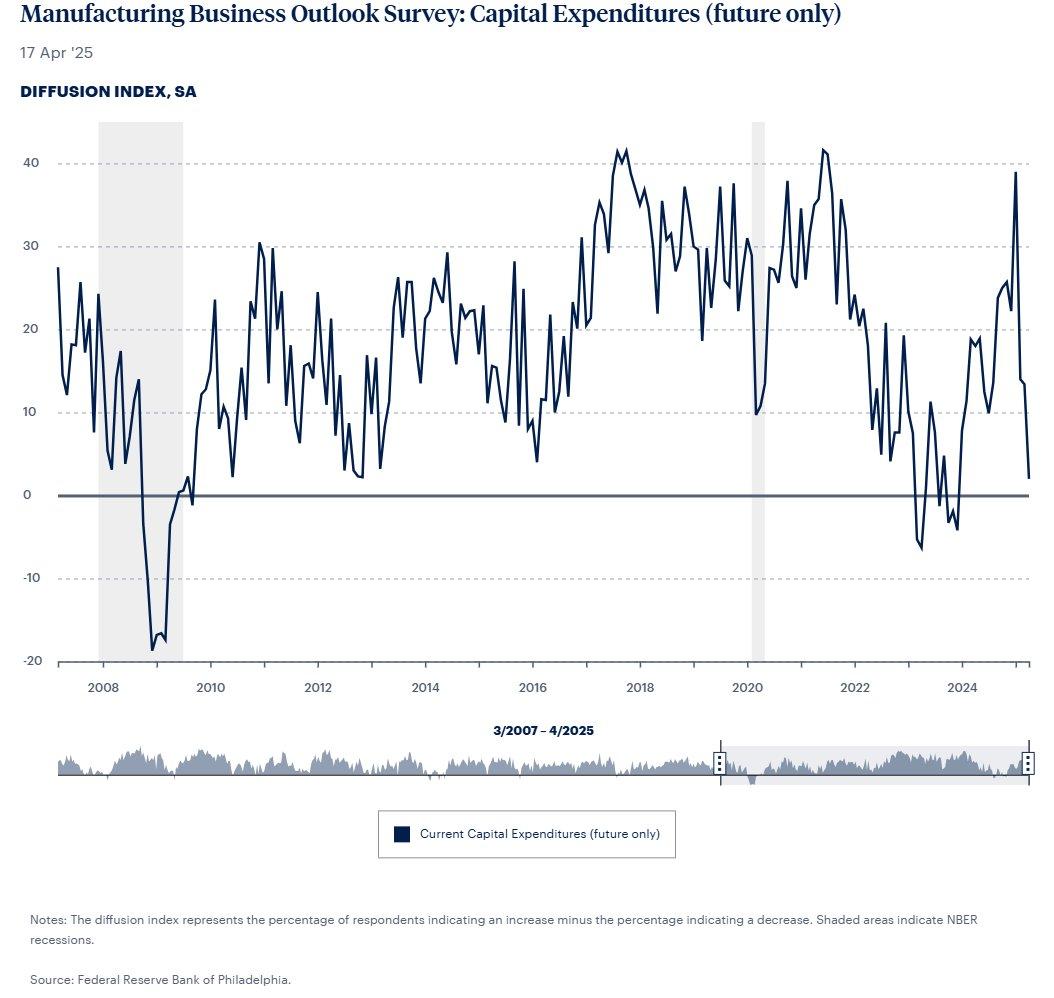

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.