With President Donald Trump’s latest tariffs emerging any minute now, I’ll save my review of their problems for another time. (Spoiler: You can bet your life savings that they’re not actually “reciprocal tariffs.”) Today we’ll instead dig into one of the administration’s most common defenses for these and other new import taxes—that they’ll supercharge domestic manufacturing investment. On the surface, the Trump team and other tariff defenders would appear to have a point: As they’re so fond of noting, multinational corporations have announced more than $1 trillion in new U.S. investments since Trump took office—announcements most often accompanied by a big press conference with Trump or another government official tying the spending directly to U.S. tariff policy. Thus, so the theory goes, the tariffs are doing exactly as Trump promised—bringing manufacturing “back” to America—and will be a net winner for the U.S. economy in the long term, even if there are some, ahem, short-term bumps along the way.

Dig a little deeper, however, and the “investment boom” thesis is riddled with problems (beyond the fact that the U.S. is already a global manufacturing powerhouse, I mean)—ones that show Trump’s tariffs to likely reduce, not increase, U.S. business investment in the coming years, especially as compared to a reasonable, freer market alternative.

How Much New Investment Are We Really Getting?

The most obvious problem is that, much like we saw during the “Bidenomics” era, it’s uncertain how much new manufacturing investment the tariffs are truly inducing. As detailed in an excellent Wall Street Journal analysis from late February, several companies have included in their big announcements “previously planned spending or developments already under way.” Most notably, Apple’s much-ballyhooed promise to spend $500 billion on factories, artificial intelligence initiatives, and more was only “slightly ahead of the company’s recent four-year pace, and the spending pledge is roughly on track with its recent investments.” Only a sliver of the promised spending, moreover, was devoted to manufacturing operations that might be affected by tariffs (and even that promise is unclear). Another $500 billion promise from OpenAI, Oracle, and Softbank “includes projects the firms initiated during the Biden administration.” Elsewhere, we see that Eli Lilly’s $27 billion is only a smidge above the $23 billion it spent here since 2020 and includes a facility in North Carolina that just recently opened. (Contra what you might hear, pharma companies have been investing in the United States like crazy in the last few years.)

As the Journal notes, these kinds of promises are hardly new. Big corporations, including Apple, routinely cozy up to a new presidential administration by giving it early “wins,” and they did it a lot during the first Trump term, too:

Much of the investment and hiring announced after Trump’s first presidential victory amounted to expansion that was already in the works, a Journal analysis found at the time. Among the not-so-new announcements: ramped-up production at Hyundai plants, warehouse hiring by Amazon.com, moving General Motors axle production to the U.S. from Mexico, and expanding a fighter-jet factory in Fort Worth, Texas.

Another reason to question these promises is that they’re just promises—and often vague ones at that. When chipmaking giant TSMC pledged an additional $100 billion in March, for example, it “did not give a timeframe for any of its new investments,” nor did it detail the type of chips the promised U.S. facilities might someday produce. With TSMC’s third Arizona facility only coming online at the end of this decade (the company hasn’t even broken ground yet), Trump could be long gone by the time these latest investments get started. Hyundai’s $21 billion investment, meanwhile, contains only one part—a $5.8 billion steel plant in Louisiana—that is new and specific, with the rest being more ambiguous pledges to expand existing capacity (which it was already expanding) or to partner with U.S. firms on other initiatives. Still other announcements include classic wiggle room, like conditioning spending on future market conditions or omitting that they might be accompanied by offsetting corporate downsizing, thus casting doubt on their ultimate net effects.

Maybe most of this investment does get deployed eventually, but—as the Journal notes (and as Capitolism has detailed)—history again gives us reason to doubt it. Back in 2018, Trump attended the Wisconsin groundbreaking for Foxconn’s $10 billion, 13,000-job project producing LCD displays, but the company “later scaled back its plans, cutting investment to just under $700 million and promising Wisconsin about 1,450 jobs.” Around the same time, Walmart and GM also promised big investments and jobs but ended up deviating little from their preexisting trends because they cut elsewhere in the United States.

These issues certainly don’t mean that all of the promised spending is just empty or repackaged nonsense, but they do give us big reasons to doubt the topline numbers that the Trump administration and its online fans keep circulating.

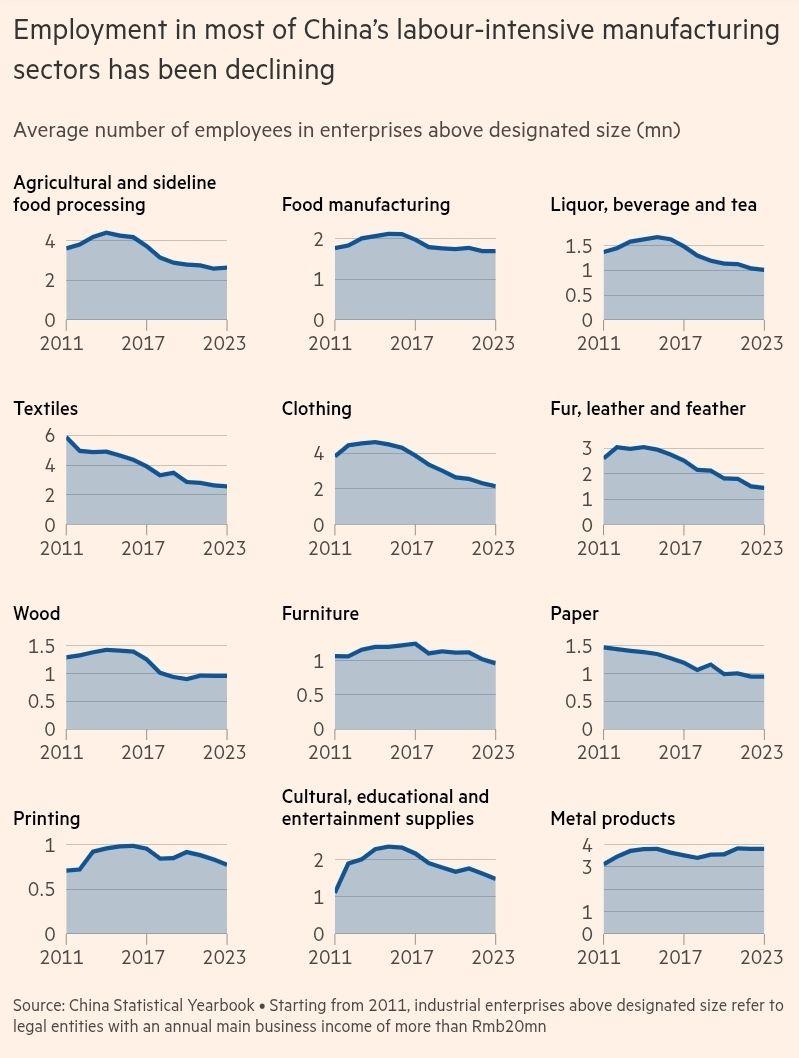

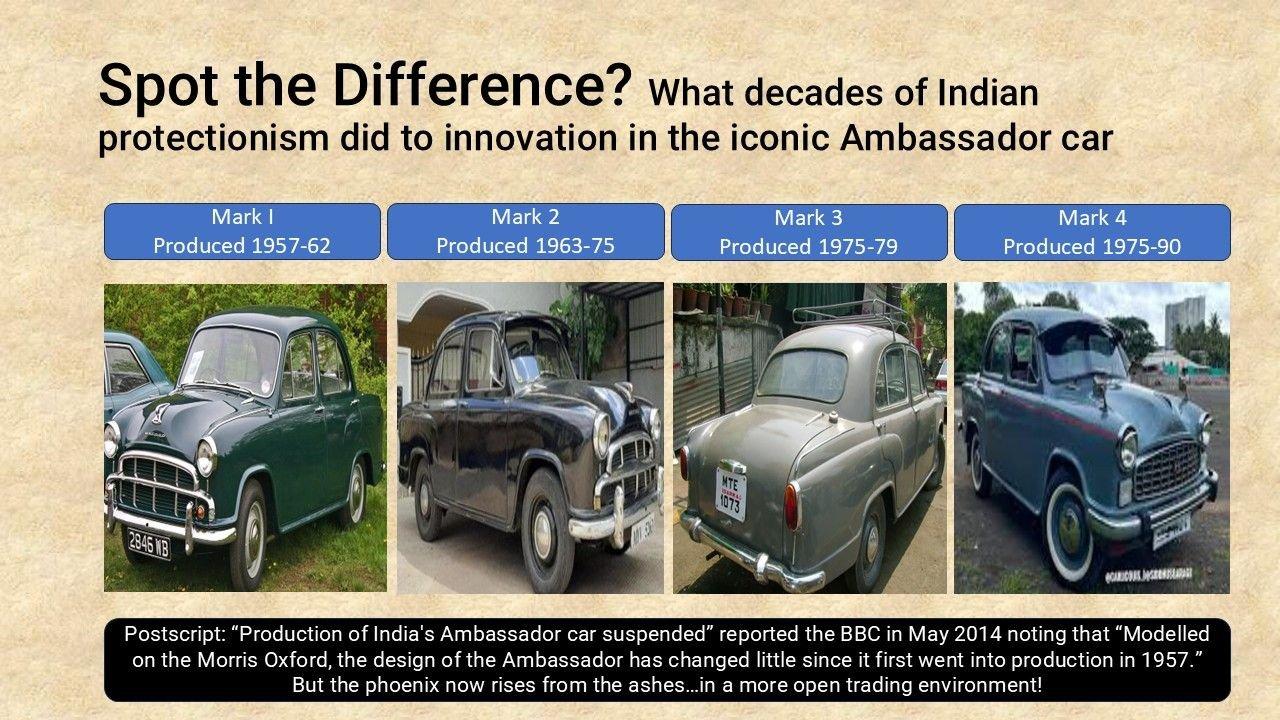

Yet even the investments that do end up getting deployed could face challenges. As I documented in a 2017 paper, for example, U.S. history is littered with examples of tariff-protected companies—makers of flatware, carpets, sheet glass, watches, etc.—shrinking, going bankrupt, or demanding even more government support to stay afloat. Capitolism has detailed other examples—in steel, aluminum, automotive, and solar—of this very same problem. And as Colin Grabow and I explained in 2023 with respect to the sad, shriveling state of protected American shipbuilding, these failures are precisely what you’d expect from protectionist policies that give domestic manufactures “a captive U.S. market and thus [discourage] scale, efficiency, innovation, and specialization.” It’s textbook stuff.

Seeing Tariffs’ Unseen Drag on Investment

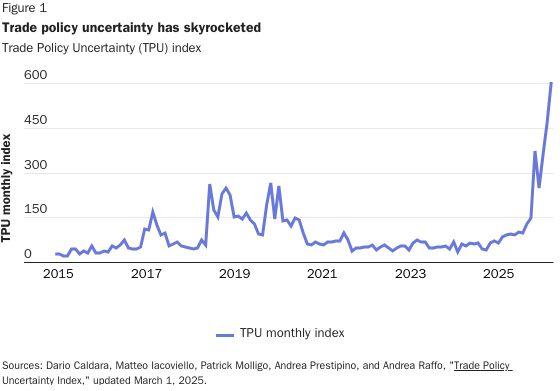

The second big problem is that the same policies ostensibly encouraging new U.S. investment are also discouraging it in several ways. As we’ve discussed, for example, trade policy uncertainty during the first Trump administration caused many investors to pause or scuttle their plans, thus reducing aggregate U.S. business investment by tens of billions of dollars in 2018 alone. This time around, the same uncertainty readings are already triple their 2018-19 levels, while Bloomberg’s version is similarly elevated.

News articles and industry surveys show that this uncertainty is causing major investor heartburn, and that the situation won’t magically improve when tariffs are imposed. In the automotive industry, for example, Bloomberg reported last week that many major carmakers with overseas operations—foreign and domestic alike—are unsure about whether to make the multiyear, multibillion dollar commitment needed to bring that production onshore or retool their U.S. facilities because they have no certainty as to how long the tariffs will be in place: “because Trump is pursuing the tariffication initiative via executive orders, not legislation, he’s leaving these measures open to change once he’s gone in a few years.” Combine that unfixable problem with the administration’s ever-changing tariff plans and the possibility of a legal challenge—a risk, Georgetown’s Jennifer Hillman details, heightened by Trump’s broad and novel use of “emergency powers”—and it’s all but certain that all those seen corporate investment promises are being matched by a significant amount of unseen investments never being made.

And even many protectionists agree.

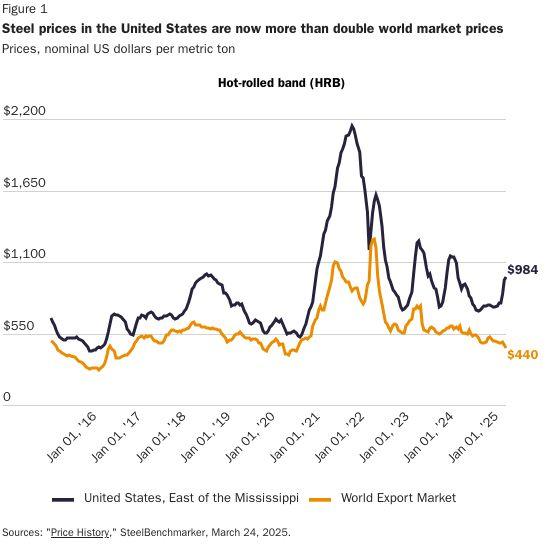

Another drag on investment will be the higher production costs that many U.S. manufacturers will face because tariffs have raised the prices of critical manufacturing inputs (whether made abroad or here). As we’ve discussed, for example, U.S. steel tariffs have pushed domestic prices to levels far above those enjoyed by manufacturers abroad:

Tariffs and tariff threats have now done the same for aluminum and copper (Comex is the U.S. price; LME is the world price):

And broader surveys of U.S. manufacturers find them expecting even higher input costs in the coming weeks.

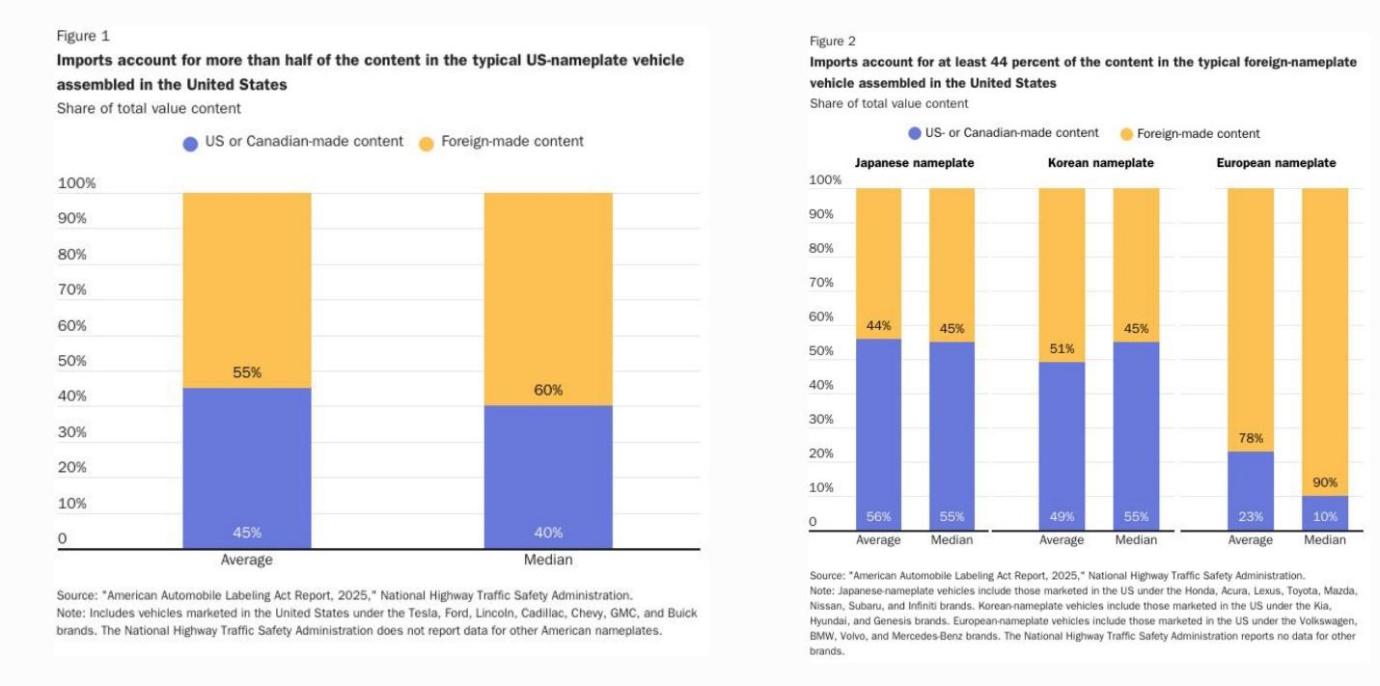

The automotive industry again provides a cautionary example of how this might all play out. Carmakers here will face elevated metals costs and, as I documented in a recent blog post, more expensive parts too. In fact, around half (or more) of a “made in America” vehicle is today sourced from abroad—content that Trump’s new automotive tariffs will eventually cover.

Tariffs might pull some automotive production onshore, but—timing, expense, and uncertainty aside—they could also do the opposite, pushing companies to places with freer access to cheaper inputs and, yes, cheaper labor too. Indeed, a recent survey of U.S. auto parts manufacturers found that roughly one third of them “said they would move production outside of the U.S. if 25 percent tariffs on Canada and Mexico stay in place for six months.” Surely, other U.S. manufacturers are in the same boat.

Finally, there’s the risk that investment shrinks even in protected companies that don’t need imports, if their prices here get so high as to cause downstream U.S. manufacturers, who can’t eat or pass on the additional costs, to cut their orders. This kind of “demand destruction” happened in steel last time around, and, once again, there’s already some evidence of history repeating as surging materials prices and declining production cause new manufacturing orders to collapse:

Relatedly, tariff champion Cleveland-Cliffs just announced that it temporarily idled several facilities and laid off more than 1,200 American workers because of waning demand by one of their key buyers, U.S. automakers. Oops.

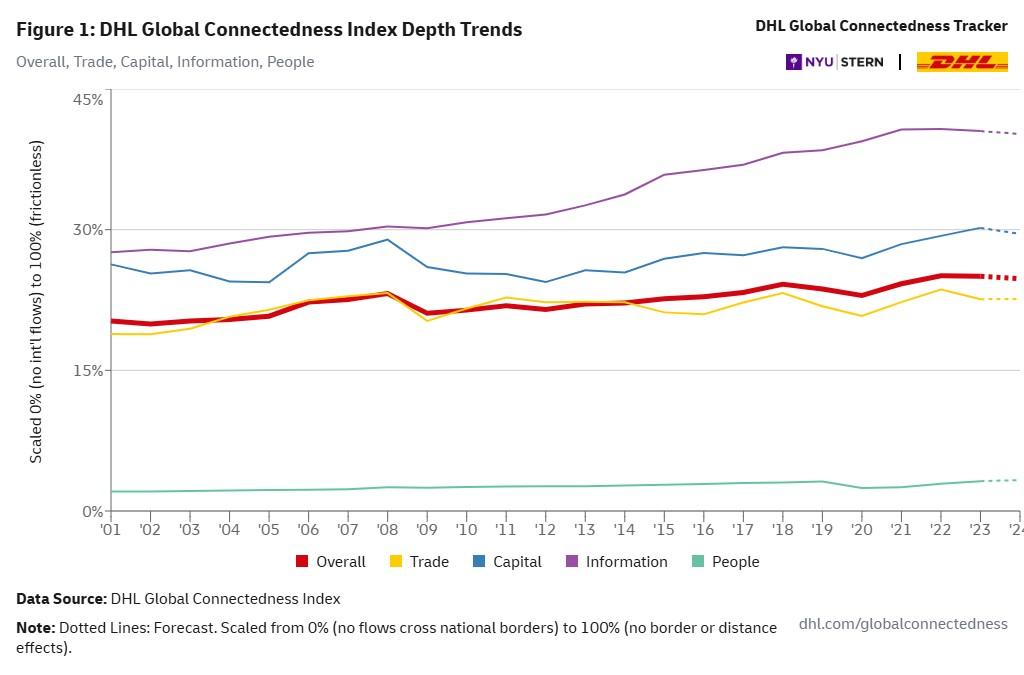

Other tariff-related headwinds will also likely materialize for U.S. investment. Trump’s tariffs are projected to lower corporate earnings and economic growth (in typical fashion), in turn causing institutional investors to look elsewhere for better returns—something that’s also already begun. MIT’s Robert Pozen reminds us, moreover, that any future reduction in the trade deficit will necessarily be accompanied by an equivalent reduction in foreign investment (see last month’s trade balance primer for more). And foreign retaliation and U.S. dollar appreciation—other typical responses to tariffs—will make U.S. exports less attractive in overseas markets and thus make the United States a less attractive export platform.

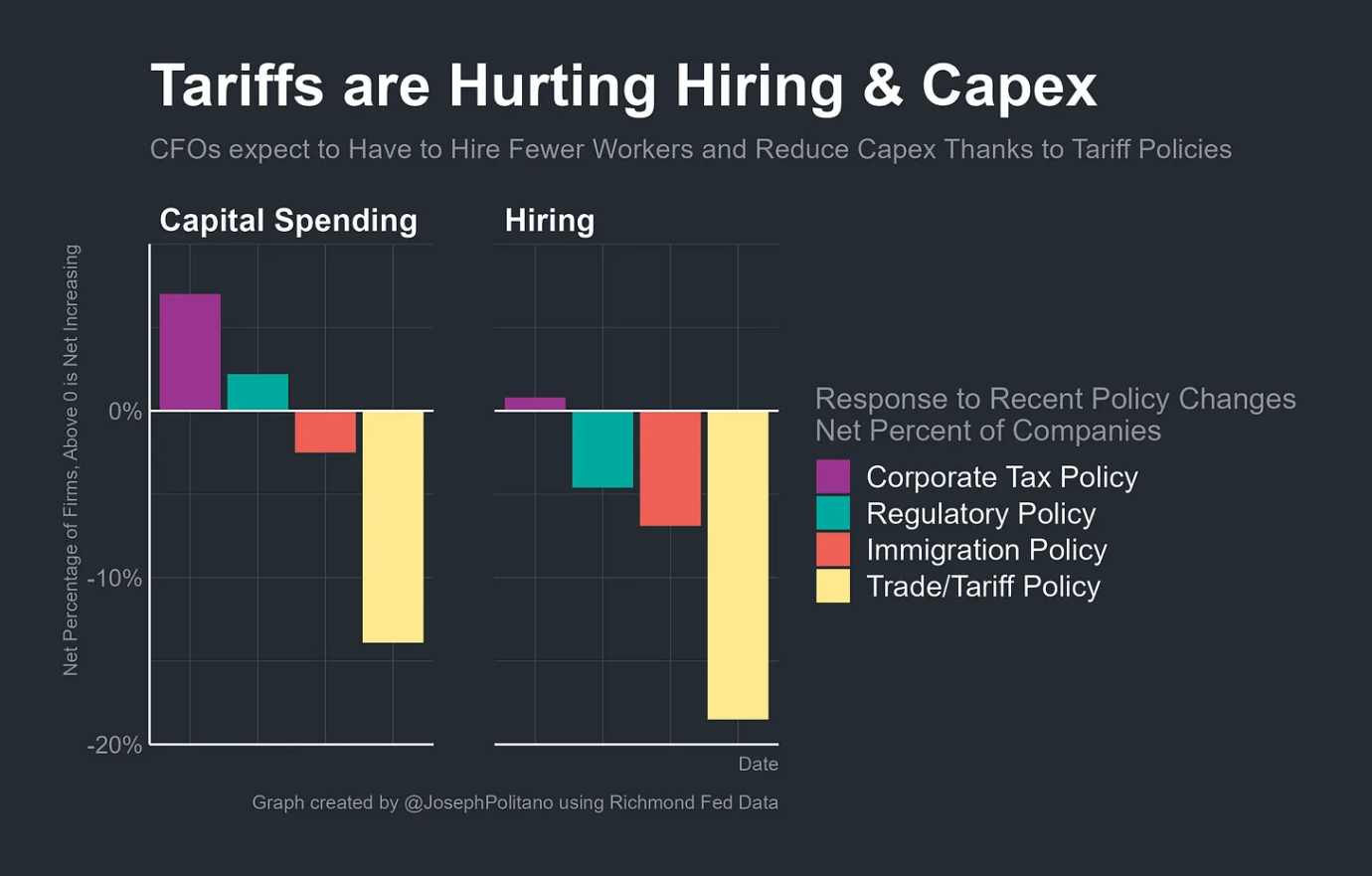

Thus, for example, the Yale Budget Lab recently projected that Trump’s auto tariffs would actually lead to a net reduction in domestic automotive investment once retaliation is considered, and Bloomberg’s Brooke Sullivan reports that several U.S.-based manufacturers have already decided to move their export-oriented production offshore to places with lower costs and less geopolitical risk. Those moves, she adds, “[raise] an interesting question about the future attractiveness of the US as a source of exports” and indicate that tariffs might “force manufacturers to isolate the US market” instead of doubling down here. The latest energy report from the Dallas Federal Reserve finds similar things, with several domestic oil and gas companies curtailing investments and at least one of them considering whether to “potentially move manufacturing out of the U.S. to support their work in Canada and other international markets.” And the Richmond Fed’s latest survey of U.S. corporate financial officers found them “saying changes in tariffs have caused them to cut their hiring and investment plans”:

In short, Trump’s tariffs might indeed cause some investors to relocate or expand their production here, but they’ll also likely cause many others to do just the opposite.

As Compared to What?

Finally, we must always ask how any real, tariff-induced increase in domestic investment measures up against an alternative policy approach. In other words, would investment here be even higher without all the tariffs and with better policies in place?

Again, we have good reason to believe that would be the case. Those 1980s automotive quotas, for example, arguably accelerated Japanese investment in the U.S. automotive sector. As I documented a couple years ago, however, this protectionism was extremely costly for consumers (around $17 billion/year in higher car prices alone), and foreign direct investment in motor vehicle and equipment manufacturing actually grew faster after the quotas disappeared than when they were in place. That’s because “there were plenty of market-based reasons to make cars here in the 1990s, regardless of U.S. protectionism,” and because NAFTA and the World Trade Organization agreements were “crucial for attracting more foreign investment and boosting overall industry competitiveness.” Economists thus generally believe that the quotas weren’t worth the high cost, and that the post-quota policy environment in the United States was actually better for the industry’s long-term health and competitiveness.

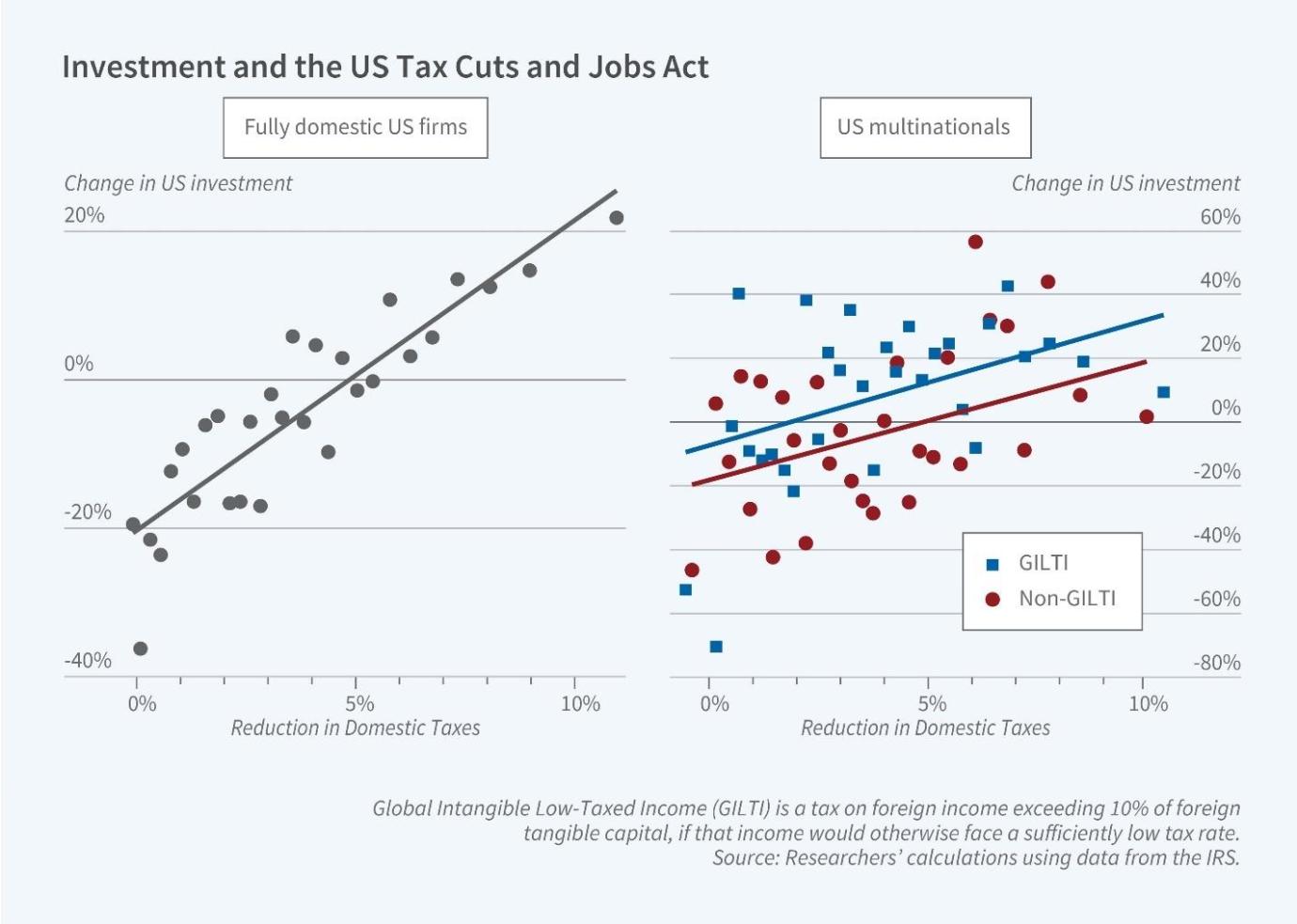

Similar issues apply today. In recent months, U.S.-based industrial companies have been spending hundreds of millions of dollars (real spending, not promises) for market-based reasons—namely, the AI boom’s insatiable appetite for data centers and electrical equipment—and “in spite of tariffs, not because of them.” We also should compare the growth and investment effects of proposed tariffs with those of a free market alternative, such as lowering the corporate tax rate or allowing businesses to immediately deduct their investments (aka “full expensing”). Similar policies were implemented in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, and careful research shows that they broadly increased U.S. investment in the years that followed. (And unlike tariffs, these tax reforms also increased economic growth.)

As my Cato Institute colleague Adam Michel just wrote, there are several pro-growth tax reforms on the table today that would achieve similar investment effects and avoid tariffs’ costs, and repealing just two Biden-era tax credits could cover the cost (with some left over). That’s a far smarter approach to encouraging investment than strong-arming corporate executives into making splashy-but-tenuous promises at a press conference.

Summing It All Up

So, some of the Trump administration’s big tariff investment announcements are old/repackaged news; others may never happen; and the ones that do happen still might struggle to stay afloat without endless government support. At the same time, past research and new reports indicate that Trump’s tariffs will likely depress business investment elsewhere in the U.S. economy by fueling unavoidable policy uncertainty, raising production costs, reducing corporate earnings and economic growth, and burdening exports. And it’s all but certain that other polices, including ones Trump himself once supported, could achieve better investment gains than tariffs and at a lower cost. Combine these realities with the fact that much of the announced investments were designed to get Trump to back off the tariffs, and there’s little reason to cheer the supposed “investment boom” tariff fans are now cheering.

Unless, of course, you just really like splashy press conferences.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.