As you’ve surely seen by now (including here in Capitolism), President Joe Biden announced a slew of new tariffs last week on “strategic” Chinese imports as part of the federal government’s mandated review of the tariffs that then-President Donald Trump put in place in 2018 and 2019. As my Cato colleague Clark Packard and several others noted shortly after Biden’s announcement, the tariffs raise a host of practical, legal, political, and geopolitical issues that we’ll mostly ignore for today. Instead, we’re going to examine the tariffs’ economic implications and why the history of U.S. trade policy—both distant and recent—should give American consumers, workers, exporters, environmentalists, and even China hawks reasons to worry.

As is often the case, the tariffs’ real risks are less about what happens tomorrow and far more about the problems that could materialize in the future, including in the very “strategic” industries the president says he’s trying to nurture.

What Biden Did

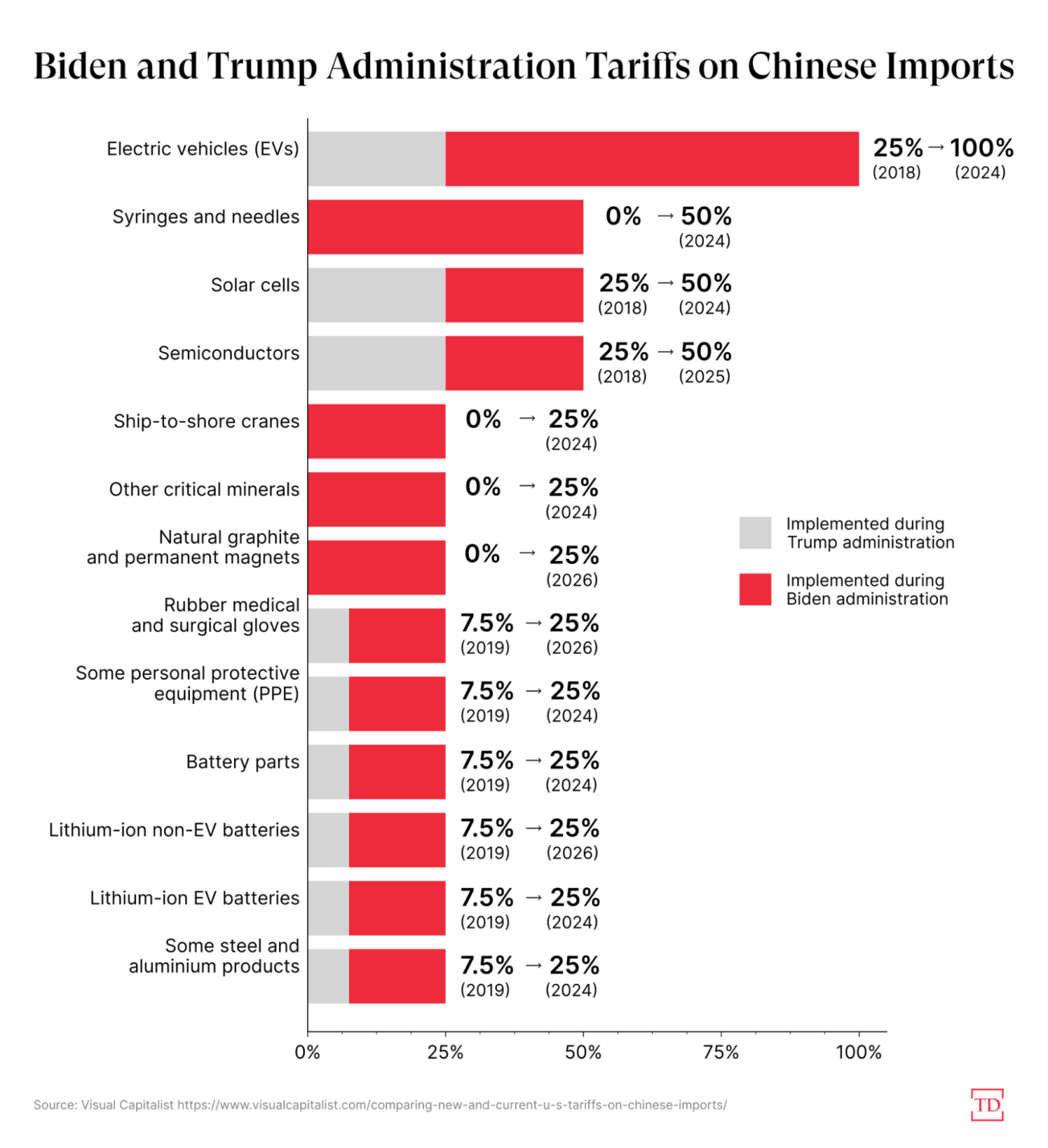

As shown in the chart below, Biden’s new tariffs will apply to semiconductors, ship-to-shore cranes and three other types of products—metals, “green” technologies (finished goods like solar panels and key inputs like “rare earth” minerals), and medical goods—and will be implemented between 2024 and 2026, depending on whether the White House believes U.S. importers need more time to wean themselves off of the goods at issue. According to the official Federal Register notice setting out the tariff details (timing, coverage, comment period, etc.), most of the new tariffs will take effect on August 1 of this year, with the delayed ones starting January 1, 2025 or 2026.

The immediate and practical effects of the tariff hikes should be relatively minor. Beyond those one- and two-year “grace periods” (which will surely encourage stockpiling), Chinese metals, EVs, and solar panels are already subject to tariffs and other trade restrictions that have effectively barred them from the U.S. market. For medical goods, the United States is unsurprisingly oversupplied after years of pandemic-related production and stockpiling; thus, while the high-priced domestic manufacturers who lobbied for the tariffs (natch) might celebrate, there’s little risk of a serious and immediate spike in U.S. PPE prices.

In the long term, however, two episodes of U.S. trade policy history give us plenty of reasons to be worried about the tariffs’ effects.

The Japan Auto Quotas of the 1980s

Let’s time travel back to the 1980s, the last time the United States embraced automotive protectionism to block a strategic rival leaning on industrial policy to make inexpensive, eco-friendly cars. Back then, the Reagan administration was worried that a flood of Japanese imports would destroy the American “Big 3” automakers and tens of thousands of United Autoworker (UAW) jobs in the industrial Midwest. So, Washington coerced the Japanese government in 1981 to implement strict quotas—“voluntary export restraints” (VERs)—on shipments of Hondas, Toyotas, and other popular brands to the United States. Sound familiar?

Anyway, we now have dozens of economic studies and reports detailing the import restrictions’ costs and benefits, and little of it bodes well for today.

Most obviously, the quotas increased U.S. car prices—not just of Japanese cars, but American and European ones, too—by thousands of dollars each, resulting in annual economic losses of as much as $6 billion (around $17.7 billion in 2024 dollars). This burden persisted throughout the 1980s and was disproportionately borne by Americans with lower incomes.

Indeed, even though Reagan wisely disavowed the quotas in early 1985, the Japanese kept them around for another decade—a testament to the durability of protectionist policies once they’re in place.

And this was just the VERs’ seen economic costs. As economist Don Boudreaux explains, there were significant unseen economic harms that are difficult—if not impossible—to quantify: “Because the VERs caused Americans to pay higher prices for automobiles… which goods and services were, as a result, denied to American consumers? And which industries in America shrank, and which jobs in America were destroyed or not created, by whatever artificial diversion was effected by the VERs of resources into increased auto manufacturing in America?”

Maybe these economic costs would’ve been justified if the VERs had supercharged the U.S. auto industry and boosted UAW rolls, but they didn’t. For starters, the quotas funneled most of the additional dollars U.S. consumers were forced to spend on cars not to the Big 3 or the UAW or even the U.S. Treasury (as tariffs can), but to foreign automakers. One study estimates that 80 percent of the consumer cost from higher Japanese car prices was transferred to Japanese carmakers (via what economists call “quota rents,” i.e., the extra profits exporters earned by selling now-more-expensive goods in the protected market). Established European automakers—and upstart Korean ones—also benefited from higher U.S. prices and more limited Japanese competition.

The quotas’ design—based on the number, not the value, of Japanese cars shipped—encouraged Japanese automakers to spend their quota rent cash on quality enhancements, marketing, and larger, more expensive models that further boosted their profits and competed more directly with the Big 3. (Japanese brands originally competed in a low-priced segment that the Big 3 mostly ignored, but Acura, Lexus, and Infiniti all got their start during the VER period.) Finally, the quotas encouraged and allowed Japanese automakers to operate in the United States as “legal” cartel, collectively deciding quota amounts and U.S. market share. (Someone alert Lina Khan!)

There’s also little evidence that the VERs put the U.S. auto industry onto a path of global competitiveness and financial sustainability. We now know that the Big 3 spent their protectionist windfall profits like protected industries so often do—unwisely. “Rather than investing more of their short run profits to quickly catch up with the Japanese,” Joshua Yount wrote in a 1993 paper, “auto executives purchased financial, aircraft, and computer companies, wrote books, headed monument restoration commissions, and gave themselves hefty bonuses for earning profits from a restrictive trade agreement.” The Washington Post provided a specific example in 1985: “General Motors Corp.’s well‐advertised Saturn project (a mere 200,000-car potential) will cost only $450 million, whereas GM spent five times that sum—$2.5 billion—to acquire Electronic Data Systems Corp., among other nonauto investments.” (Saturn is, of course, out of business today.)

To the extent that Detroit automakers did improve quality during the 1980s, they still badly lagged the Japanese throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. In fact, the quality gap between them and U.S. automakers actually widened by 1990 because the Japanese were also innovating in the 1980s, aided by all that quota rent cash. As a result, the Big 3 continued to experience falling sales and market share, layoffs, plant closures, and delayed investments while the quotas were in place.

There’s a reasonable argument to be made that the VERs did encourage Japanese automakers to invest more in the United States (though economists debate how much of that investment was really owed to the quotas). However, most of the new Japanese auto plants in the United States were non-union facilities located in “right to work” states—and thus came at the direct expense of the UAW workers and Rust Belt communities that the VERs were intended to bolster. As the Philly Fed explained in 1990:

The majority of the transplants are located in the rural Midwest and the mid‐South, distant from the traditional stronghold of U.S. auto manufacturing. As a result, the dislocations at the local level resulting from layoffs and shutdowns at the older plants have not been eased by the transplants. A complete assessment of the impact of U.S. auto industry restructuring must take these costs into account.

As I noted a couple years ago, the move away from Detroit and a unionized American automotive manufacturing workforce has accelerated since the early 1990s. (And the latest failed unionization vote at Mercedes in Alabama indicates that this trend ain’t gonna change any time soon, either.)

The Cascading Solar Panel Protectionism of Today

“But Scott,” I can already hear you saying, “that was decades ago and not even tariffs. This is about China and national security and climate change!!” Well, fortunately for you, a modern example can answer your (very sincere and informed) concerns: the United States’ decade-plus attempt to subsidize and protect its way to a healthy domestic solar panel industry. Alas, it’s another cautionary tale.

As part of America’s last grand industrial policy experiment, the 2009 American Recovery and Investment Act, the U.S. government doled out billions in subsidies to domestic solar manufacturers. Almost immediately after the funds started flowing, problems started emerging, with China once again being blamed for U.S. companies’ financial difficulties. So, shortly after the highly publicized failure of industrial policy poster child Solyndra, the United States in 2011 launched antidumping and countervailing duty (AD/CVD) investigations of solar panels and cells from China. That case ultimately resulted in import taxes of more than 30 percent in 2012, subsequently reducing targeted products but increasing imports of other types of solar products from China and Taiwan. So, the still-struggling U.S. industry filed another, broader AD/CVD case in 2013 and again won final duties (ranging from about 10 percent to more than 200 percent) against those imports in early 2015.

Alas, these tariffs also didn’t result in a substantial, long-term increase in U.S. solar manufacturing and employment, despite higher solar panel prices here and billions in state and federal subsidies. As one recent Bloomberg report recalls, “most of the factories built as part of that [Obama-era] manufacturing push have long since shuttered.”

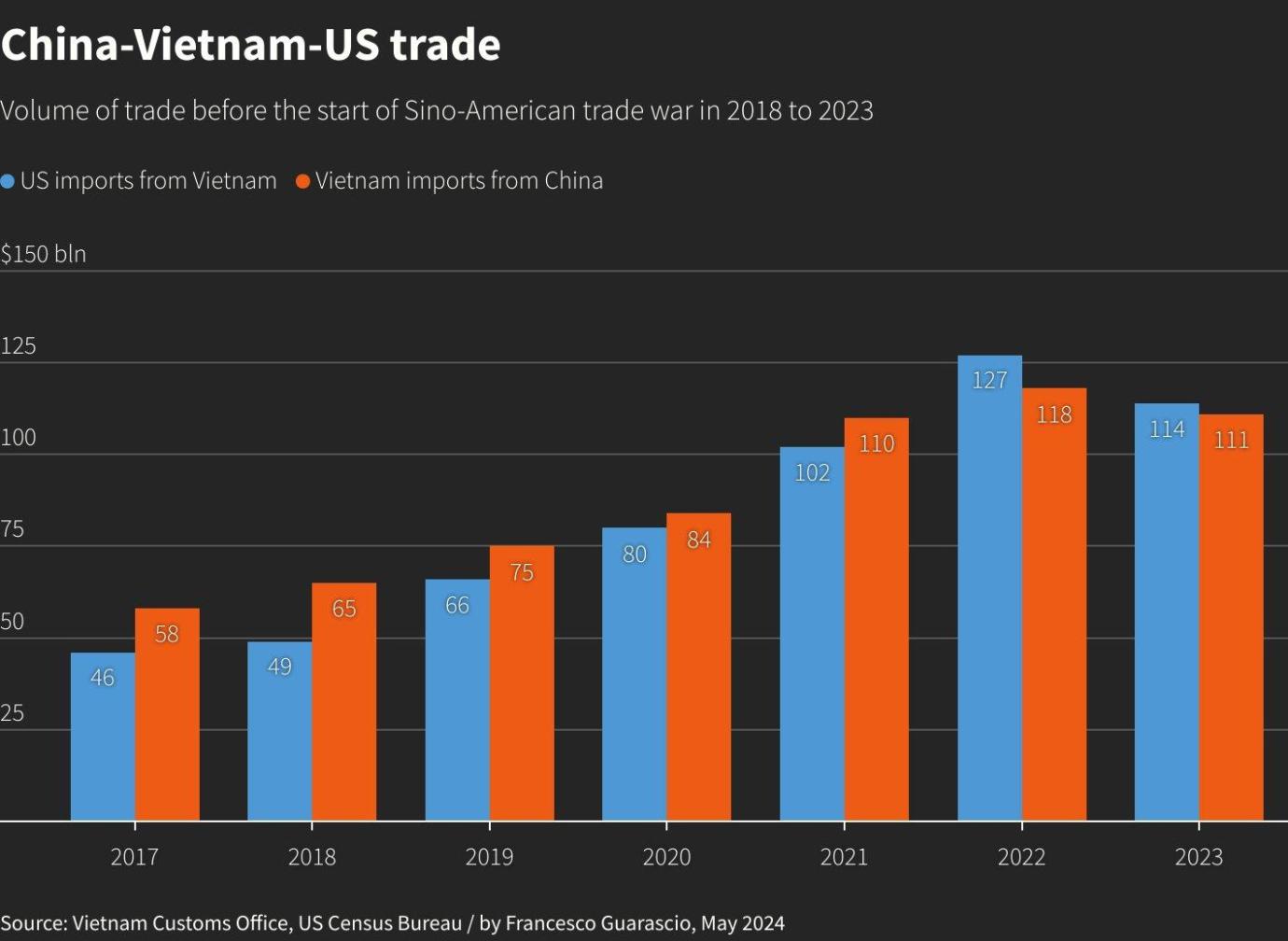

Instead, global solar manufacturing investment again shifted in the wake of the U.S. import restrictions, but this time to Southeast Asia, not the United States. So, U.S. solar producers pursued two new actions to block these imports, too:

- In 2017, they filed a new “safeguard” petition against all solar cells and modules, regardless of source. They won again, and President Trump imposed global tariff rate quotas in February 2018, with rates varying on the year and quantity imported. Those safeguards were supposed to expire in 2022, but President Biden extended the measures for four more years—through February 6, 2026.

- In 2022, they filed an “anti-circumvention” investigation against imports from Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam, alleging that these panels, which accounted for more than 75 percent of total US solar panel imports that year, contained Chinese inputs that were just being assembled in the Southeast Asian countries and thus should be subject to the 2012 China duties. The Commerce Department agreed, but Biden in September 2022 suspended new duties of up to 200 percent for two years to give solar panel installers time to adjust (and his subsidies time to work).

In 2018 and 2019, Trump imposed an additional 25 percent tariff on Chinese solar products as part of his broader “Section 301” tariffs on about $300 billion in annual imports. To top it all off, the U.S. government has initiated several other trade actions against Chinese solar imports suspected of containing polysilicon—a key solar input—made by forced labor from China’s Xinjiang region. (Never mind, of course, that it was the original 2012 duties on Chinese imports that helped kill off the United States’ burgeoning polysilicon industry.)

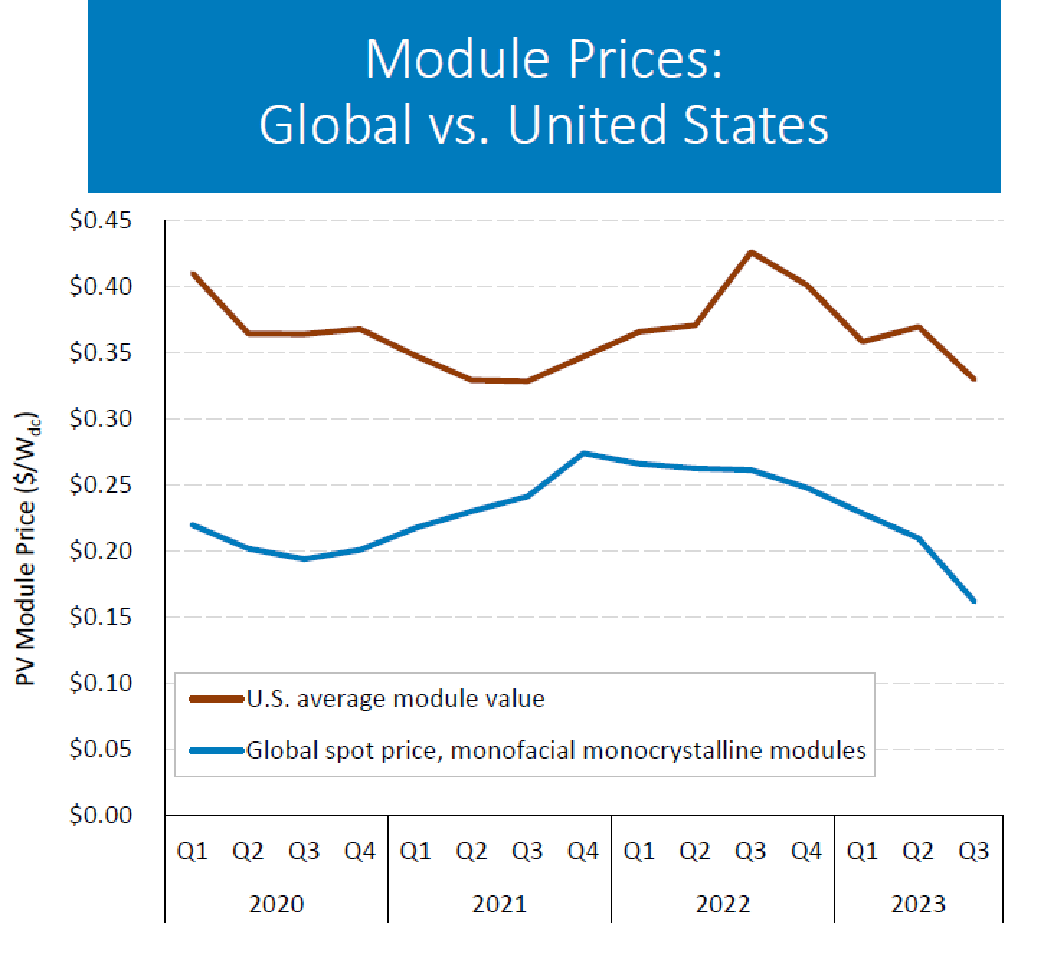

One can reasonably defend the merits of at least some of these trade actions (especially the forced labor restrictions), but two things aren’t up for debate. First, thanks to highly mobile investment capital, non-trade headwinds facing U.S. manufacturing, and good ol’ trade diversion, what started out as “China tariffs” have morphed into much bigger and broader protectionism, with all the attendant harms you’d expect. Most obviously, solar panel prices in the United States are well above those for the rest of the world—a substantial “premium” that Biden’s own Energy Department says is owed to U.S. tariffs and other trade “frictions”:

Installation is similarly more expensive. As the Wall Street Journal documented in 2022, “American homeowners … pay $2.65 per watt on average to install a residential solar system today,” while “the equivalent fully installed residential solar costs are $1.50 in Europe, $1.25 in Australia and $1 in India—because these places practice, and get the benefits of, free-market capitalism in their solar markets.” Unsurprisingly, these higher prices have undermined several U.S. solar installation companies and cost tens of thousands of American jobs in the industry.

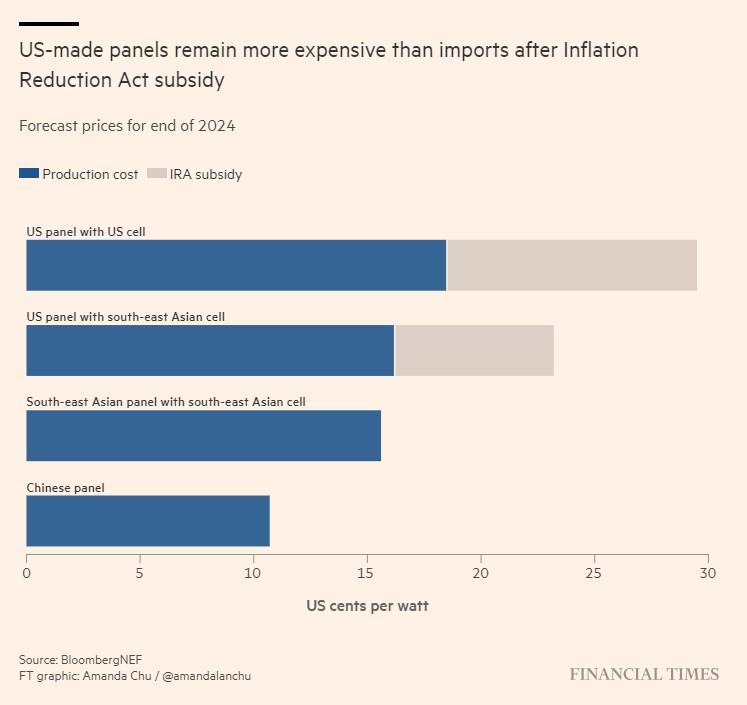

Second, we are still waiting on all this protectionism and industrial policy to produce a stable and vibrant domestic solar manufacturing industry. Indeed, even after all the tariffs and billions more in Inflation Reduction Act subsidies, U.S. solar manufacturers are still struggling because of—you guessed it—imports. In particular, the Financial Times reported in March that new U.S. manufacturing projects are getting canceled or delayed because of a surge of Southeast Asian imports that, emphasis mine, “remain far cheaper than US-made counterparts even accounting for tariffs and IRA subsidies.”

Last week, the Commerce Department initiated another AD/CVD case against the same four Southeast Asian countries targeted in 2022, no longer focusing on China and company-specific “circumvention” but instead seeking country-wide duties of at least 70 percent on all imports from those places. Biden’s announcement last week also included a slew of other solar protectionism, including the termination of a “loophole” in the global safeguard measures (which U.S. courts have already ruled isn’t a loophole) allowing imports of “bifacial” (double-sided) solar panels that, the FT reports, are “often used in large solar projects, one of the fastest-growing forms of clean energy in the country.”

In Washington today, the lesson of the last decade-plus of U.S. solar protectionist failure is that we just need even more protectionism.

Lessons Abound, as Usual

As Capitolism readers surely know by now, the Japanese automotive quotas and solar panel tariffs are not isolated examples of the problems that arise when Washington turns to import restrictions to achieve industrial policy dreams. The history of U.S. trade policy is littered with examples of “targeted and temporary” protectionism blossoming into broader and longer-term government support for companies that actually become less globally competitive and thus turn back to Washington when the tariffs, subsidies, and mandates are about to run out.

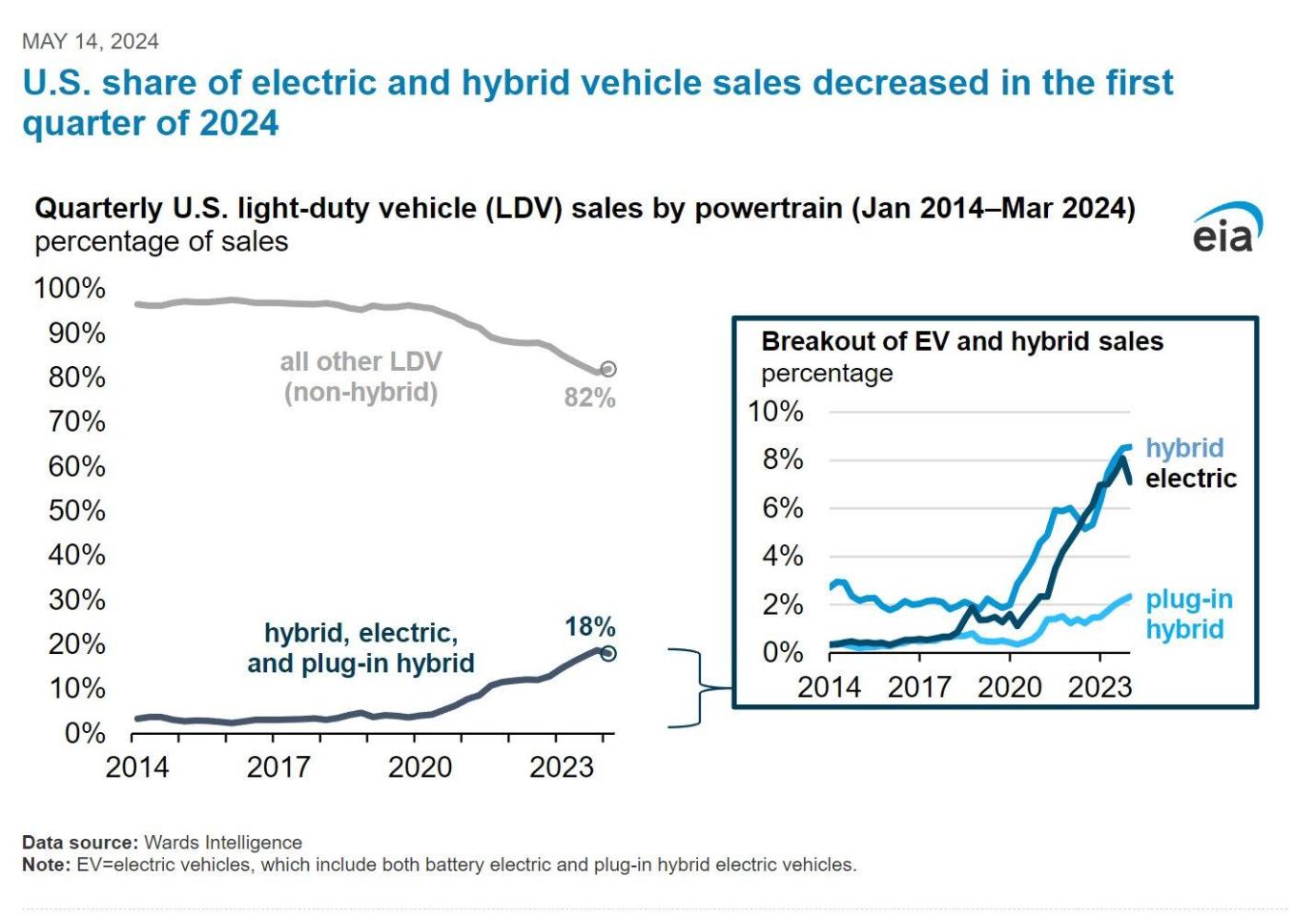

So, what does this mean for the new Biden tariffs? First, as Packard explained for EVs, we should obviously expect adverse price effects, even if not right away:

Chinese EV imports today raise some different issues than did Japanese cars in the 1980s, but the consumer harms of US protectionism will likely be similar. Today, by many accounts, China is producing some pretty good quality EVs at prices well below those for most EVs in the US market (even with generous IRA subsidies). Effectively banning Chinese EVs will thus give remaining automakers in the United States room to keep EV prices higher than they’d otherwise be, to American consumers’ detriment. And, unlike the case of Japan in the 1980s, it’s all but certain that Chinese automakers will be barred from investing in the United States to jump this new tariff wall.

Other experts agree that we shouldn’t expect a Japan-line increase in new Chinese investment in the United States in response to Biden’s new tariff wall; if correct, it’ll exacerbate the tariffs’ economic harms.

Higher prices, as the Journal’s Stephen Wilmot noted a few days ago, might be a particular issue for EV batteries and minerals, given their importance for lower-priced, American-made EVs and China’s role in the battery supply chain. He estimates that the battery tariffs could add about $1,000 in extra costs for the standard-range Tesla Model 3, potentially discouraging Tesla production in the United States and encouraging it in China (where the company can serve foreign markets … like Canada). Ford’s made-in-Mexico Mustang Mach-E might also feel the pinch, depending on whether the tariffs eventually apply to finished EVs that are imported into the United States with key Chinese parts.

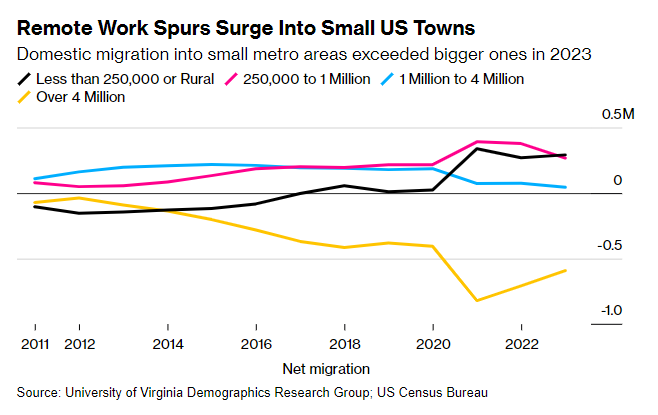

And that raises the second concern: that these tariffs are just an opening salvo in the United States’ efforts to “strategically decouple” supply chains from China. Indeed, Biden administration officials are already planning to use future United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) negotiations to target made-in-Mexico steel and EVs that come from Chinese-owned factories or that contain China-origin inputs. The Commerce Department is now also investigating “connected vehicles” that automakers worry will result in new restrictions this fall that extend beyond Chinese-made EVs to any vehicle with Chinese parts. (Korean automakers have been advised to diversify their supply chains and hire a good lobbyist. Sigh.)

Chinese EVs, investment, and intermediate goods are also flowing into other countries—such as Korea, Canada, Brazil, Vietnam, and Hungary (alert the national conservatives!)—meaning more U.S. trade pressures are likely on the horizon, either from imports connected to Chinese companies or ones displaced by Chinese goods in the home market and exported to the United States’ “safety valve” economy. If so, the United States will become even more isolated than it already is.

This doesn’t even begin to explore what happens if other, non-China countries also start making low-priced, high-quality EVs and exporting them to the United States. As we’ve discussed, many imported EVs are already barred from getting U.S. consumer subsidies, despite some—like these two Korean models—getting rave reviews. If imports continue to perform well here at the expense of unionized U.S. production, will tariffs be next there too?

We’ve now entered an era in which the question isn’t whether U.S. EV prices will be higher than global EV prices, but instead how much higher they’ll be.

Regardless, we’ve now entered an era in which the question isn’t whether U.S. EV prices will be higher than global EV prices, but instead how much higher they’ll be. That’s a real problem for a domestic industry hemorrhaging cash and struggling to gain traction—in part because of high prices.

Finally, history gives us little reason to expect all these tariffs to produce new and thriving domestic industries in the years ahead. As the Washington Post recently noted, “If American companies … fail to use the latest tariff protection to catch up in zero-emission vehicles, the market that is their chief source of profits ultimately could be at risk.” But, as even industrial policy fans have recently acknowledged, that risk is the most likely outcome, and I’ve yet to hear a single coherent, well-backed reason why Detroit automakers and other industries insulated from foreign competition (and probably earning less abroad, thanks to retaliation) will someday emerge from an era of U.S. tariff protection as large, productive, and innovative global champions. (And this assumes, of course, that the tariffs actually will end someday—“temporary” U.S. pickup truck tariffs have been in place since 1964!)

Just yelling “national security” doesn’t cut it.

Summing It All Up

Although the immediate effects of the Biden administration tariffs will probably be muted, history reveals a plethora of troubling, longer-term risks. Prices will likely be higher, discouraging consumption of the very environmental goods the government is trying to promote and harming downstream American manufacturers that need access to low-cost inputs. (Indeed, even Biden’s own trade representative—by proposing to exclude dozens of Chinese industrial machines from last week’s tariffs—acknowledged that imports, even from China (gasp!), can help the U.S. industrial base.) Import protection will probably spread, meaning prices will move even higher still and the potential for geopolitical blowback—from China and other nations—will grow. Barring a major change in incentives and departure from precedent, the protected U.S. companies and workers at issue probably won’t come out the other side of this healthier and more productive and probably will instead turn to lobbying for even more government support. (They’ve already started, by the way.) If that ends up being the case, it won’t be because of libertarian obstructionism or brilliant Chinese industrial policy (which, even in EVs, has real problems). It’ll be par for the protectionist course in America, and, perhaps most depressingly, it’ll leave plenty of other, better U.S. policy options for dealing with China left untouched along the way.

But hey, maybe this all works out in the end, and maybe—contra the history and the widely held view of non-partisan experts here and abroad that Biden’s moves were driven by politics and will again fare poorly—domestic EV, solar, and other “strategic” industries getting protection become globally dominant enterprises. If they do, President Biden’s gamble will have paid off, and the industries Biden targeted last week won’t join steel, sugar, shipbuilding, and other protectionist darlings on the pile of American also-rans. Even then, however, it’d still be a big gamble—one that succeeded despite, not because of, U.S. protectionism.

Chart of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.