In the pantheon of modern political and social satire, Saturday Night Live’s Unfrozen Caveman Lawyer undoubtedly deserves a spot. For those unfamiliar with the recurring 1980s classic, a thawed-out Neanderthal named Keyrock—played by comedic genius Phil Hartman (RIP)—becomes a cynical lawyer (and later a politician) who uses his “simple caveman” origin story to manipulate onlookers and win cases or votes. Wikipedia summarizes the running gag well:

Keyrock would speak in a slick and smoothly self-assured manner—but with obviously feigned naiveté—to a jury or an audience about how things in the modern world supposedly “confuse and frighten” him. … He would then list several things that confounded him about modern life or the natural world, such as: “When I see a solar eclipse, like the one I went to last year in Hawaii, I think ‘Oh no! Is the moon eating the sun?’ I don’t know. Because I’m a caveman—that’s the way I think.” This pronouncement would seem ironic, coming from someone who had, for example, just ended a brisk cell phone conversation, or indeed attended law school. Keyrock would always finish a disquisition, however, by asserting in a burst of righteousness that nevertheless, “There is one thing I DO know …” That one thing would be that his client was either innocent, or was entitled to several million dollars or more in both compensatory and punitive damages for an injury. The jury or counsel is invariably swayed by Keyrock’s argument.

As Wikipedia adds, the skit is a clever take on how “simple folk wisdom” can be remarkably (frustratingly) persuasive for the general public, even when it’s clearly ridiculous and being employed by an obvious phony out for personal gain. Watch enough real world law or politics, and you’ll see Keyrock’s schtick everywhere—especially when it comes to economics.

We saw it again last week when former Fox News star Tucker Carlson expressed jaw-dropping, Keyrock-like amazement at the abundance on display at a Moscow grocery store—an episode, Carlson goes on to say, that “radicalized” him against the current U.S. economy. Watch for yourself:

Carlson’s Moscow adventures have attracted a litany of much deserved criticism and insightful commentary—including from The Dispatch’s own Kevin Williamson and Nick Catoggio, both of whom rightly note that the United States economy crushes Russia’s on various measures of national wealth (e.g., per capita gross domestic product). National Review’s Jim Geraghty provides other America-favorable comparisons on average salaries, public corruption, and life expectancy, while George Mason’s Ilya Somin points to all the people trying to leave Russia and come to America as clear signs of which economy is more attractive today. They are certainly not alone.

However, being the unofficial Ambassador of American Grocery Abundance, I feel obligated to weigh in here, too. And fortunately (I guess), there’s plenty left to say.

Let’s start with that supposedly incredible Russian grocery store technology. As National Review’s Dominic Pino first pointed out, the futuristic Russian amenities that so captivated Carlson—coin-operated shopping carts, in-store bakeries, cart escalators, etc.—have been available at American grocery stores, even discount ones, for decades. (See, for example, Aldi or Wegman’s or Lidl.) Many American stores lack these amazing sci-fi technologies (LOL) simply because they’re unnecessary—not because we’re suffering from some sort of “radicalizing” national decline or whatever. And, of course, U.S. supermarkets are constantly innovating with new items, amenities, and technologies like smart carts, dynamic pricing, scan-and-go, made-to-order meals (ordered online or at a kiosk), and artificial intelligence—a testament to intense competition in the low-margin U.S. industry.

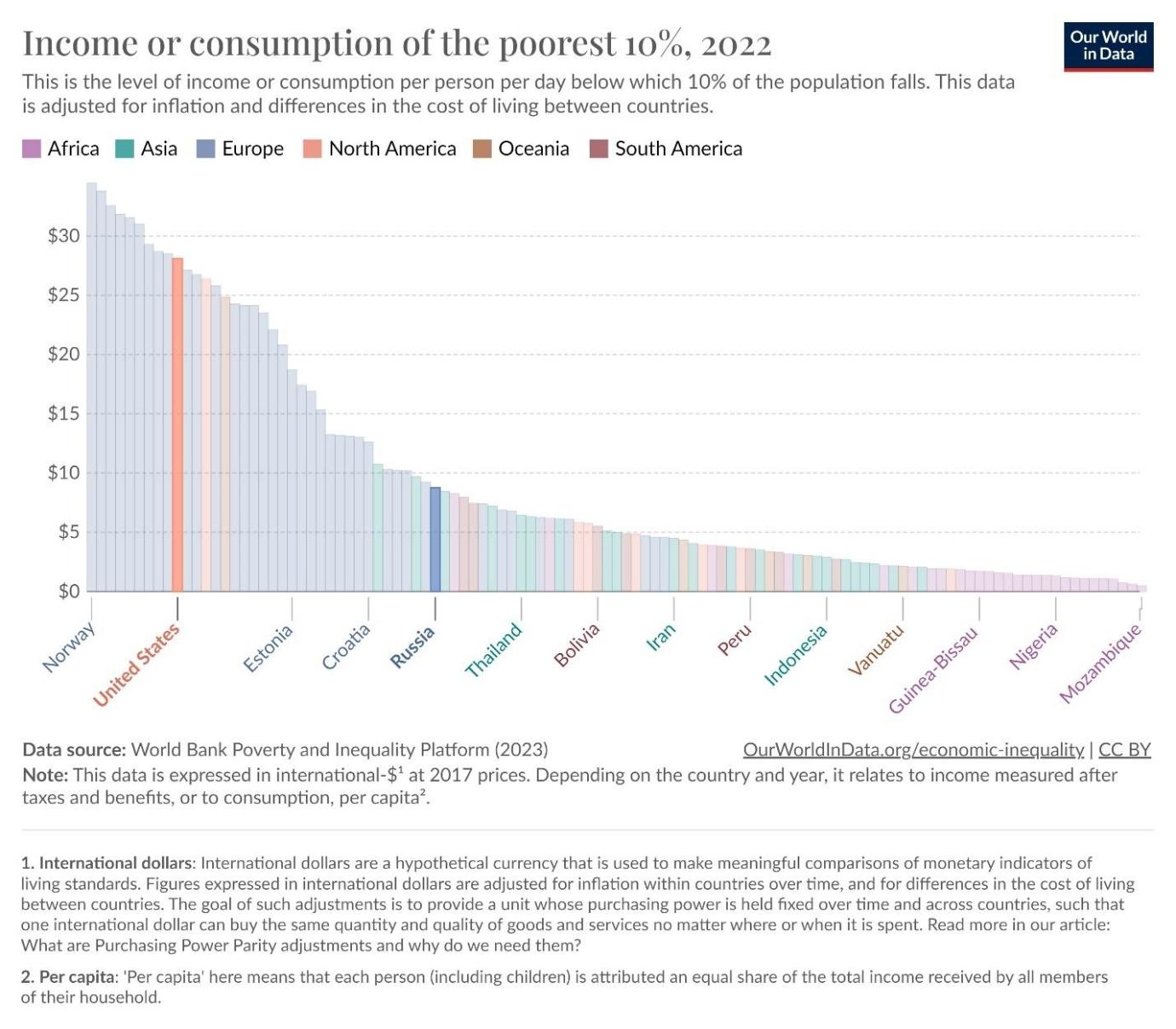

Carlson’s economics are similarly mistaken. First, he seemingly fails to understand that the surprisingly low price for his groceries—about $100 when he and his crew expected $400—is a tribute to American, not Russian, wealth. According to the latest data from the World Bank, for example, the median American worker would need to work about a day and a half to afford $100 worth of groceries, while it’d take the median Russian almost a week. A similar gap applies to the poor: The daily income or consumption of the poorest 10 percent of Americans in 2022 was more than three times that of their Russian counterparts, after adjusting for inflation and cost of living—a wealth differential that’s actually widened (from around 2.5 times) over the last decade:

This doesn’t mean, of course, that America’s poorest have it easy today. But it does mean that what might seem “cheap” to most Americans would be totally out of reach for most Russians.

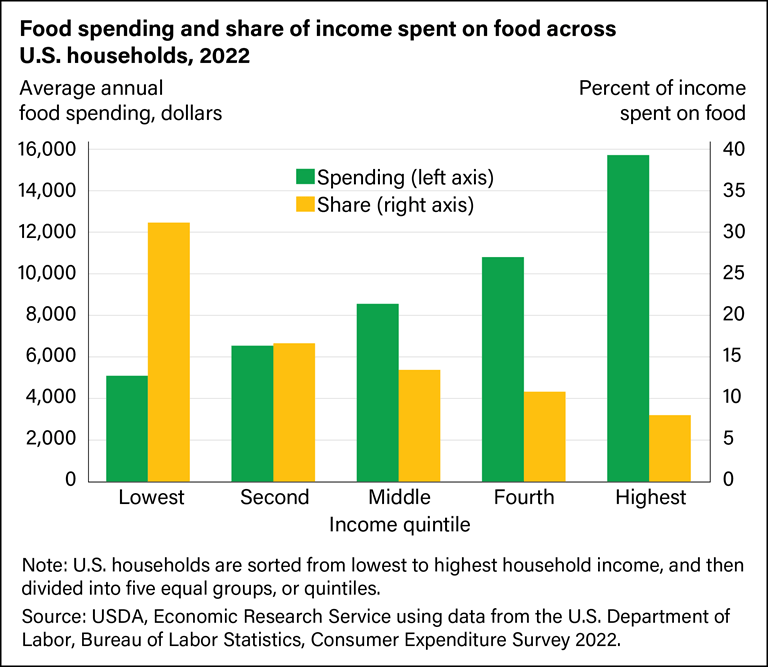

Indeed, thanks to high U.S. incomes and widely available supply (hooray globalization!), food is still incredibly cheap in America—especially when compared to Russia. According to the USDA, about 28.9 percent of an average Russian consumer’s total expenditures in 2022 was spent on groceries alone. In the United States, by contrast, the share was a mere 6.7 percent—the lowest of any country and only a smidge higher than it was before the pandemic.

The USDA adds that only the poorest Americans spend on all food categories (groceries and restaurants) what average Russians spend on just groceries*:

To the extent these figures changed in 2023, it’s probably to Russia’s detriment, given recent food inflation there. (Food prices in the United States increased about 5 percent last year—high by our standards but not, as we’ll discuss next, by Russian ones.)

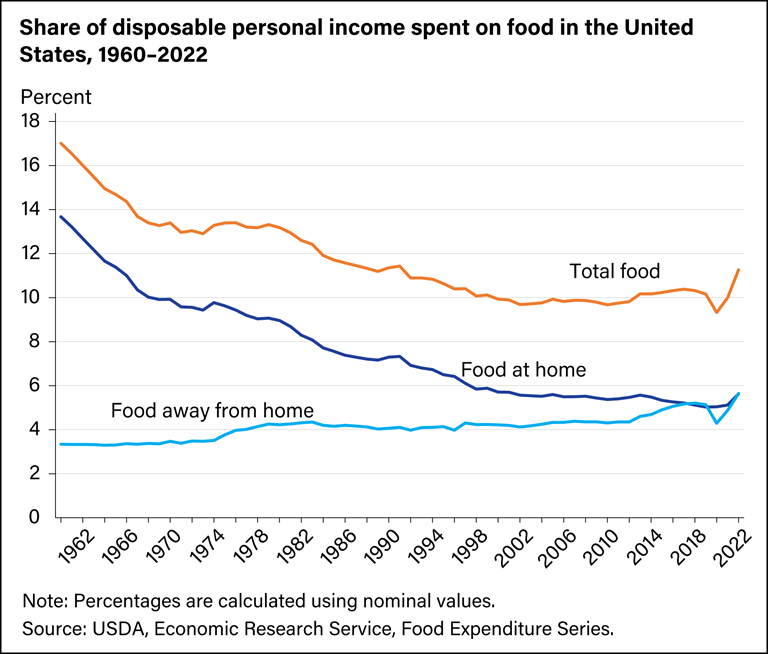

The increasing affordability of food in the United States is—thanks to innovation and trade—a long-term historical trend worth celebrating. Yet, even in the early 1960s, Americans’ grocery bills were nowhere near where Russians’ bills are today:

None of this means, of course, that U.S. policy can’t be improved to boost American grocery abundance even more (food protectionism is an obvious place to start). But it does mean that, by both historical and global standards, American grocery shoppers have it pretty darn good.

Finally, Carlson fails to understand how exchange rates make things in Russia seem even cheaper to Americans than they really are. Here’s Pino again:

Americans will frequently be impressed by how far their money goes in foreign countries. It’s expensive to travel abroad, but once you actually get there, a lot of stuff seems really cheap. That’s because American tourists benefit from a strong dollar, and they have high incomes by global standards. It doesn’t really tell you much about the quality of life for people who live in the foreign country.

That’s especially true the past few years. In 2022, the dollar was trading at 20-year highs relative to other currencies. It’s down slightly from that today, but it is still very strong.

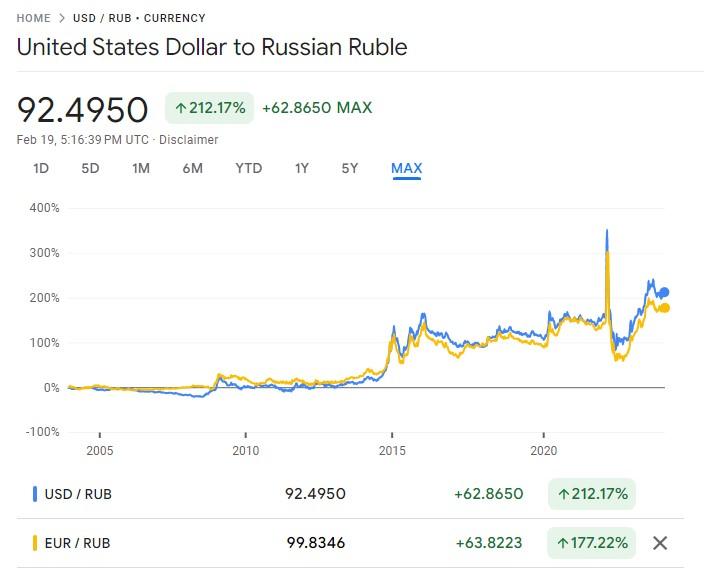

As Pino notes, the U.S. dollar indeed remains strong globally, but it’s particularly strong in Russia, where the ruble has been on a decadelong slide accelerated by the Ukraine invasion and related sanctions. Ten years ago, for example, $1 got you about 35 rubles; today, it gets you more than 90. The trend is similar, though recently less severe, for the euro—indicating that the ruble’s weakness is more about Russia’s bad economy than the dollar’s strength:

As the Wall Street Journal explained last summer, a weak ruble isn’t all bad for the Russian government—it can boost certain exports (e.g., oil) and has helped fuel the Russian war machine—but it’s undeniably terrible for Russian consumers:

Russia’s economy by most measures has been diminished by Western sanctions, but has held up better than expected thanks to a gusher of oil revenue and heavy government spending on war-related production. … But a weakening currency, which increases the cost of imports and drives up inflation, is a significant worry for Moscow. The Kremlin has to deal with the rising costs of the war while shielding the population from its consequences.

The Russian population is indeed feeling those consequences: Inflation in Russia has been brutal in recent years, especially for food:

Russia’s Central Bank has raised its key lending rate four times this year to try to get inflation under control and stabilise the ruble’s exchange rate, as the economy weathers the effects of Moscow’s war in Ukraine and retaliatory sanctions by the West. The last time it raised the rate — to 15%, doubled that from the beginning of the year — the bank said it was concerned about prices that were increasing at an annualised pace of about 12%. The bank now forecasts inflation for the full year, as well as next year, to be about 7.5%.

Although that rate is high, it may be an understatement.

“If we talk in percentage terms, then, probably, (prices) increased by 25%. This is meat, staple products — dairy produce, fruits, vegetables, sausages. My husband can’t live without sausage! Sometimes I’m just amazed at price spikes,” said Roxana Gheltkova, a shopper in a Moscow supermarket. Asked if her income as a pensioner was enough to keep food on the table, customer Lilya Tsarkova said: “No, of course not. I get help from my children.” Without their assistance, “I don’t know how to pay rent and food,” the 70-year-old said.

Figures from the state statistical service Rosstat released on 1 November show a huge spike in prices for some foods compared with 2022 — 74% for cabbage, 72% for oranges and 47% for cucumbers.

In short, the ruble’s weakness may have made Carlson’s grocery bill seem cheap, but that’s definitely not something that actual Russian grocery shoppers are celebrating. (Funny how he didn’t—ya’ know—interview any of them, eh?)

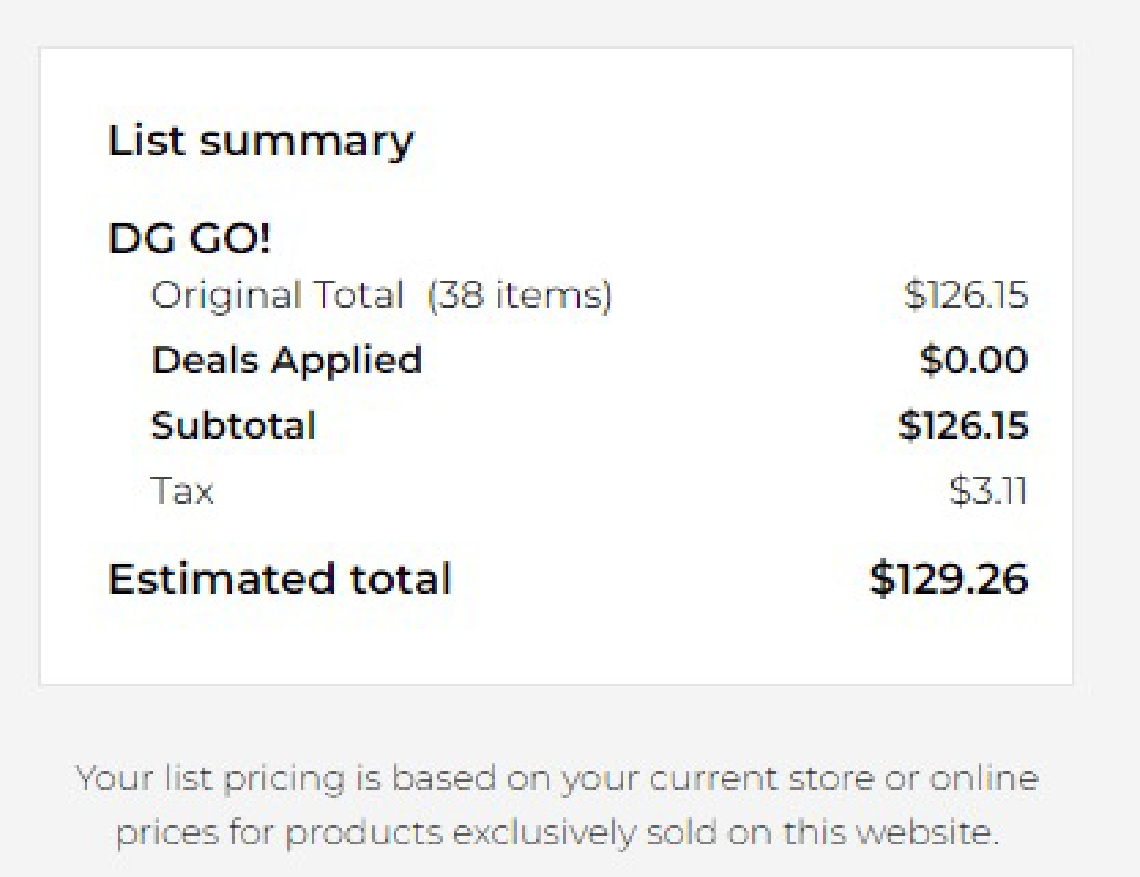

All these World Bank, USDA, and currency data are surely useful, but probably the easiest way to see America’s continued grocery abundance—even after years of inflation—is to just go shopping. I did just this over the weekend by heading to the website of a nearby store and creating my own shopping list based on the Carlson video above. My list is admittedly an imperfect comparison—I couldn’t find everything (like a giant gourd?) in Carlson’s shopping cart and can’t be positive I saw everything—but I tried my best (judge for yourself). I even added extra things to replace what I couldn’t find and just in case I missed a few things in the video.

All told, I bagged 38 items covering what a small family might need for several days of meals at home: flour, sugar, cereal, milk, eggs, butter, bread, pasta/sauce, frozen pizza, olive oil, vegetables, fruit, chicken, beef, ham, chips, cookies, coffee, wine, etc. I then blindly totaled it all up and discovered that the grand total was— drum roll—just about $20 more than what Carlson spent in Russia:

Maybe this comparison is a little off. As noted, I couldn’t find certain things—bagged apples and fresh bread, for example—at the store I chose and may have missed a few things. On the other hand, I very likely could have purchased these same items for even less at, say, the Food Lion near my house, where a quick indicative search showed that many foods on my and Carlson’s lists (beef, chicken, cereal, and eggs) were actually cheaper, while the overall selection was much wider. I also didn’t clip any coupons or search for any special deals (and I didn’t try to buy in bulk at a place like Costco).

But I chose this store for a reason: It’s one of the very dollar stores that Carlson himself has denigrated as a supposed symbol of American economic decline. Yet, even at one of these supposedly terrible places—and even after several years of food inflation in the United States—groceries here are pretty inexpensive by Carlson’s own (absurd) standards. No fancy income or currency adjustments needed. Increase the total bill by 50 percent more, in fact, and you’d still be far below the $400 that Carlson and crew said they expected in Russia.

It all speaks volumes, not only about the “radicalizing” grocery shopping experience but about the “radicalized” grocery shopper himself.

Summing It All Up

Carlson misunderstands Western grocery store technology; misunderstands Americans’ comparative food abundance (in historical and global terms); misunderstands exchange rates; and misunderstands what groceries actually cost out here in Real America, even at the places he hates. His unfrozen caveman-like amazement and commentary are modern American populism—heavy on “elite” condemnation, comically light on substance, and dripping with ulterior motives—at its finest.

At least when it came to Keyrock, we were all in on the joke.

*Editor’s note: This piece was updated to clarify that only the lowest-income Americans spend, as a percentage of their income, as much on groceries and restaurant food as the average Russian spends on just groceries.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.