I’ll never forget the first time I was personally exposed to the power of the New York Times to drive the national news. It was March 2005, and I was president of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE). In February we’d written a letter to Le Moyne College, a small Catholic school in New York, warning them that they’d breached their promises of academic freedom by summarily expelling a student for advocating corporal punishment in schools (cancel culture isn’t new, by the way).

Back at the beginning of the battle against university censorship, it was often hard to get national media outlets to pay the slightest bit of attention to free speech on campus. Local media would cover stories, but in the absence of national coverage we’d often labor to convince the public that campus intolerance was a real problem. Then the New York Times came calling, and on March 10, 2005, Patrick Healy wrote a long story about the Le Moyne case.

I remember walking into our conference room, putting the newspaper on the table, and telling our team, “Get ready for the phones to explode.” Sure enough, within the hour we had fielded calls from multiple networks. The lesson was clear: If the Times says something is a story, then it’s a story.

And I’ll never forget the first time I was personally exposed to the power of Fox News to put a cause (and a person) on the conservative map. By 2006 I had moved on from FIRE to start the Center for Academic Freedom at the Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF). A young pro-life activist named Lila Rose had entered Planned Parenthood clinics in California posing as a pregnant, underage teenager and had recorded employees who appeared willing to conceal what looked like statutory rape.

When she went public with the tapes, Planned Parenthood claimed she had violated California criminal law when she recorded the conversations. She reached out to ADF for help. It turns out that Bill O’Reilly—then the king of primetime cable news—was interested in her case. Really, he only wanted to talk to Lila, but she needed her lawyer present, so I drove to a Nashville studio, sat down in the chair, and promptly botched my appearance.

I was terrible. I wasn’t ready for O’Reilly to be somewhat hostile and dismissive, so I stumbled over my words and barely made sense. I couldn’t wait to get out of the chair. As I’ve written before, however, for a time that short appearance was my best career development since graduating from law school. I could add a vital bullet point to my bio: “David French has appeared on Fox News.”

Since that time, the Times and Fox have only grown more powerful. With the demise of local news, national outlets have increased their influence. The New York Times has become a “digital behemoth.” In March, the Times’s own Ben Smith put the paper’s influence in perspective:

The gulf between The Times and the rest of the industry is vast and keeps growing: The company now has more digital subscribers than The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post and the 250 local Gannett papers combined, according to the most recent data. And The Times employs 1,700 journalists — a huge number in an industry where total employment nationally has fallen to somewhere between 20,000 and 38,000.

More:

The Times so dominates the news business that it has absorbed many of the people who once threatened it: The former top editors of Gawker, Recode, and Quartz are all at The Times, as are many of the reporters who first made Politico a must-read in Washington.

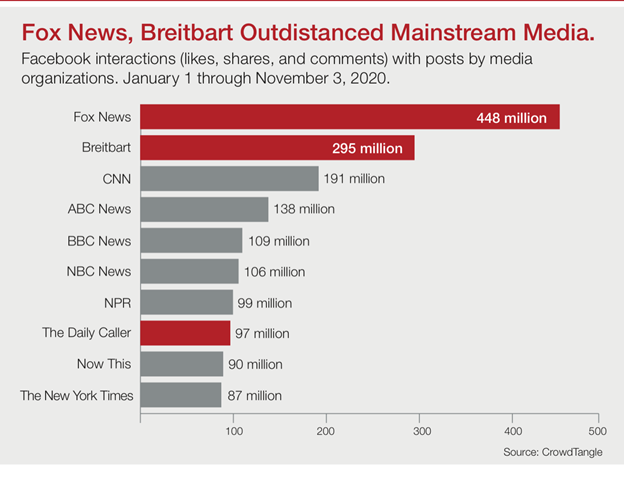

And what of Fox? It’s not just the 800-pound gorilla of conservative media, it may well be the most powerful news channel in the world. While its ratings struggled early this month, it has spent 20 years on the top of the cable news charts. It’s a profit-making machine, raking in more than $570 million in pretax profits in the last quarter alone. Its web traffic rivals the New York Times, and its social media presence (especially on Facebook) dwarfs its competitors:

Their dominant market positions grant Fox and the Times disproportionate influence over public opinion and a disproportionate influence over the rest of the industry. Thus it’s vitally important for the body politic that these institutions are healthy. Sadly, they are not.

Let’s start with the Times. For month after month, the media world has been transfixed by Times drama. Editorial page editor James Bennet was forced out after he granted op-ed space to Sen. Tom Cotton to argue that Trump should deploy troops to maintain peace in American streets. My friend Bari Weiss publicly resigned, citing intolerable harassment from far-left colleagues. The paper made stealth edits to its vaunted, Pulitzer-winning 1619 Project to remove its most contentious claims.

(In fact, the 1619 project demonstrates the Times’s power and the consequences of its mistakes. The 1619 project influences the curriculum in schools across the land.)

Days ago, the paper fired one of its leading public health reporters, Donald McNeil Jr., after high school students on a Times-sponsored trip complained that he quoted the N-word in a discussion about race. (To be clear, he didn’t intend to use the word as a slur. He allegedly used the word in a discussion about the word.) Later reporting indicated that he’d clashed with students on other issues as well, including the prevalence of race discrimination in modern America.

I could go on—including to the evidence that the paper maintains a rather obvious set of double standards. For example, star left-wing employees seem to have more freedom to stumble. Nikole Hannah-Jones, architect of the 1619 project, “doxed” a reporter at the Washington Free Beacon by sharing his phone number on Twitter with no serious consequence.

To its credit, the Times still allows its journalists to cover its shortcomings, and its own Ben Smith said this about the recent controversies:

I think it’s a sign that The Times’s unique position in American news may not be tenable. This intense attention, combined with a thriving digital subscription business that makes the company more beholden to the views of left-leaning subscribers, may yet push it into a narrower and more left-wing political lane as a kind of American version of The Guardian — the opposite of its stated, broader strategy.

Bari Weiss also stated the problem succinctly. The New York Times is rapidly becoming print MSNBC:

No one throws stones at the Times with more glee than smash-mouth commentators on Fox News. But they live in a glass house. No, that understates things. They live in a glass cathedral.

Any roundup of “fake news” scandals in the Trump years has to reserve serious space for Fox News. Remember the absolutely dreadful Seth Rich scandal, where both the news and opinion side of the network dedicated time to the malicious falsehood that a murdered DNC staffer was the “real” source of the DNC email leaks? Did you spend much time on the channel during the post-election period, where its falsehoods have earned it a multibillion dollar defamation suit from Smartmatic?

And if we want to speak about toxic workplace environments and cancel culture, Fox is the place to do it. Its #MeToo scandals are now the stuff of film and legend. And while Fox’s loss of Chris Stirewalt is The Dispatch’s gain, its recent purge of the man who became the face of its contentious (and correct) election night call of Arizona for Biden, combined with its promotion of conspiracy theorist (and defamation-suit defendant) Maria Bartiromo to a prime-time tryout had more than a few echoes of the Times’s notorious double standards.

Indeed, Fox is a double tragedy. In concept, it represents the best way to combat institutional media bias—build a competing institution. In practice, parts of its programming have become downright clownish. For example, Tucker Carlson’s attempts to defend QAnon believers and Marjorie Taylor Greene by labeling attacks on QAnon as attacks on “conscience” and attempts to strip committee assignments from Greene as an attack on “free inquiry” were embarrassing to watch.

I know that both the Times and Fox still have a legion of good journalists on the payroll. Some of my favorite people in media work in both places. Heck, our Dispatch co-founders Steve Hayes and Jonah Goldberg are both Fox News contributors. I just recorded an appearance on The Argument, one of my favorite Times podcasts. I’ve appeared on Fox. I’ve written for the Times.

But it’s that exact combination of immense power and continuing virtue that make it imperative that external critics fight for the reform of both institutions. I believe in creating new institutions to preserve liberal traditions. That’s one reason why I joined The Dispatch. That’s why I’m proud to serve on the Board of Advisors of Yascha Mounk’s Persuasion. But it’s also vital to preserve (if we can) the institutions we have.

The New York Times can choose not to be a partisan paper. Fox can choose not to be Newsmax. If we have any hope at all for the civic education of the American people or for an informed understanding of politics, we should do what we can to make sure that our most powerful media organizations make better choices.

The Times and Fox cannot mistake institutional wealth for institutional health, and their sickness can’t be contained to their own newsrooms. The virus of their dysfunction spreads to American politics and American culture. There are some institutions that are too important to fail.

One last thing …

Readers, I’m getting more ambitious. You’ve long heard me talk about Elon Musk’s mission to Mars, but why stop there? Is it even feasible to think about interstellar travel? (Can you tell I’ve still got The Expanse on my mind?) Here’s a cool PBS YouTube about five ways to travel to the stars. Ever heard of a pion rocket? Me neither, but can we please invent one before I get too old to fly?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.