My grandmother was a treasure. Outside of my parents, Ruth French (“Nana” to us) was the single most influential person in my life. She was a history teacher from rural Mississippi. She was widowed in middle age (I never met my grandfather; he died in a tractor accident when my Dad was still in college), but from the first moments I remember, she exuded an indomitable, exuberant spirit. I loved her. I loved being with her—through every stage of life.

As a young kid, I couldn’t wait to get to Nana’s house. I was always sad to leave. From the moment I learned to read, she immersed me in history. We toured the battlefields of the South together, and she got me a souvenir cannon at each one. From Yorktown to New Orleans to Shiloh and Vicksburg and Appomattox we traced the history of American conflicts.

As a teenager, I’d spend long lazy afternoons in Mississippi, silently reading next to her. She read and quoted poetry. I read her library of biographies and ate the ice cream sandwiches she always kept stocked for each visit. And then, one day, when that love of reading and learning that she implanted deep within me paid off with a surprise admission to Harvard Law School, the very first person I raced to the phone to call was my grandmother.

I’ll never forget my law school graduation. Her eyes were shining as she took in the pageantry and history of Harvard. That evening, one of my classmates had rented a boat in Boston Harbor and invited friends and family to join him for an evening of food, drinks, and dancing. In fact, the picture above is of her, taken that very night.

Nana, normally an extremely social person, kept to herself and sat quietly in a chair in the back of the boat and gazed at the Boston skyline. Concerned, I sat down next to her and asked if she was okay. She was advanced in years, and I thought she might be tired. Instead, she turned to me and smiled. “Shoot me now,” she said, “while I’m happy.”

When I met Nancy, I knew she was the one, so I took her to meet Nana immediately. I even asked Nancy to marry while walking through Nana’s neighborhood. I didn’t have a ring. I asked her impulsively, while we were sitting down next to a drainage pipe (not the most ideal setting). Nancy said yes.

Nana died three years later after complications from heart surgery—just before we could tell her that we were naming our firstborn daughter after her. She was 81.

Why do I tell my grandmother’s story? Because the coronavirus crisis is exposing the vulnerability of our nation’s senior citizens, and it’s our duty to care for and protect those who have given us so much. It’s time to remind ourselves of their incalculable value.

Our grandmothers and grandfathers (and for some of us, our fathers and mothers) are physically vulnerable to the virus itself, they’re vulnerable to fear and fraud, and they’re vulnerable to callous disregard. While we all know senior citizens who seem sharper and healthier than men and women decades their junior (my retired math professor father rises early and works every day on our family farm—rain or shine), we also know friends and family who are in a state of decline. Their health is failing. Their minds aren’t quite as clear.

And we love them desperately. We value every moment with them. The prophet Isaiah said of the Lord’s servant that “a bruised reed he will not break, and a faintly burning wick he will not quench; he will faithfully bring forth justice.” The meaning is clear—in imitation of Christ, we are to nurture and protect those who are weak.

As a practical matter, during a pandemic this is easier said than done. Yesterday my friend Ben Shapiro tweeted something poignant and true:

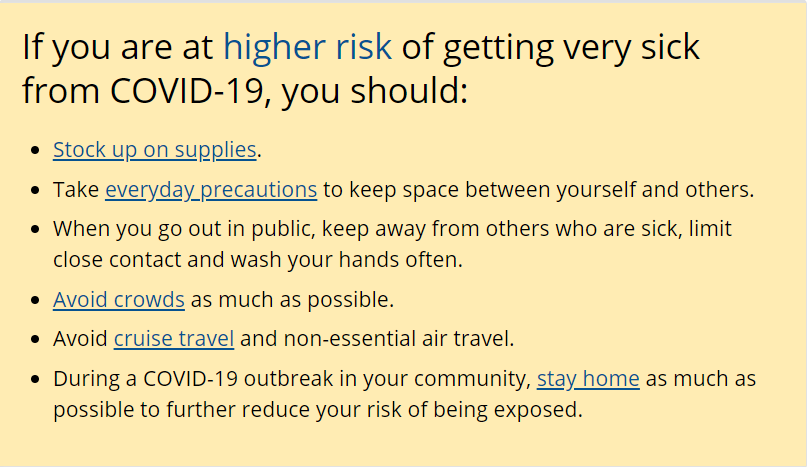

If we have been out in the community, then pulling our parents and grandparents physically closer to us can expose them to greater harm. If we are in part responsible for the care of older and sicker Americans, then we need to adjust our own behavior. If we’re present with older parents and friends, then their risk tolerance should be our risk tolerance. Know, understand, and apply the CDC guidance for older adults and those with serious chronic medical conditions. If your local government has imposed even stricter precautions, apply the local guidance.

But love and care require more than caution. We must check in by text and phone when visits are unwise. We must make sure they have food and necessary medicine. We must provide supplies when it’s not safe for them to leave the house. They should never feel abandoned.

But we must do even more. We must defend those we love from fraud and fear. And by fraud I don’t merely mean the standard array of scammers and hucksters who typically prey on our nation’s seniors. I mean defending them from terrible counsel from the very people so many millions of seniors trust.

I’ve written at length about the inexcusable avalanche of misinformation that for weeks cascaded out of the Oval Office and conservative media. I won’t repeat all of the false comparisons of COVID-19 to the flu or the common cold, all the president’s false declarations that the virus was already diminishing or thoroughly under control, or the claims that hyping the virus was yet another media conspiracy to undermine the president. But that misinformation was delivered to an audience that was disproportionately older and disproportionately likely to disbelieve contrary information.

The president’s declaration of emergency and the joint public/private show of force at Friday’s White House press conference should at least start to dispel the belief held by all too many seniors that there was nothing to worry about, that they shouldn’t change their plans. After all, the person and the information sources they trust the most had told them this entire crisis was overblown. The result is stories like this:

But dispelling complacency should not lapse into fearmongering. Taking precautions can work. We know they can work because we’ve seen them work in other nations. Prevention is not panic.

And yet even after the president’s Wednesday address that announced draconian measures to combat the virus, terrible takes still abound. Watch Jerry Falwell Jr.—one of the president’s leading faith advisers and the president of one of America’s largest Christian universities—peddle fraud and fear on Fox:

First, he accused people of “overreacting.” Then, he alarmingly (and ridiculously) speculates that the virus is a North Korean bioweapon. It’s an astonishing display, and it’s evidence of the extent to which partisanship can corrupt a believer’s mind.

The obligation to our seniors is sacred. The Fifth Commandment declares, “Honor thy father and thy mother; that thy days may be long upon the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee.” This statement is no mere admonition to be kind to your parents. As the Westminster Larger Catechism declares, “By father and mother, in the fifth commandment, are meant, not only natural parents, but all superiors in age and gifts; and especially such as, by God’s ordinance, are over us in place of authority, whether in family, church, or commonwealth.”

In fact, the Catechism says that honoring those superior in age also means the “defense and maintenance of their persons and authority.” Protecting your parents, your grandparents, and your vulnerable neighbor is your moral duty. In a time of deadly trouble, I’m reminded of God’s ancient admonition to the people of Israel—“I call heaven and earth to witness against you today, that I have set before you life and death, blessing and curse. Therefore choose life, that you and your offspring may live.”

People of faith should not presume that we face a new challenge. There is ancient wisdom that can guide us as we reject fear (“for God gave us a spirit not of fear but of power and love and self-control”) and also reject recklessness or negligence. Stupidity in the name of fearlessness is still stupidity. The words below, from Martin Luther, have rocketed around the Christian corners of the Internet. They were wise when written—in the face of a far deadlier plague—and they are wise now:

I shall ask God mercifully to protect us. Then I shall fumigate, help purify the air, administer medicine, and take it. I shall avoid places and persons where my presence is not needed in order not to become contaminated and thus perchance infect and pollute others, and so cause their death as a result of my negligence. If God should wish to take me, he will surely find me and I have done what he has expected of me and so I am not responsible for either my own death or the death of others. If my neighbor needs me, however, I shall not avoid place or person, but will go freely.

It’s a simple, yet powerful, declaration. Do not be afraid. Do not be reckless. Serve others but do not endanger others, and as we do, we must remember that the Lord’s servant protects the bruised reed, and there are many millions of bruised reeds in our midst.

One last thing …

A number of readers enjoyed me sharing a traditional hymn last week. Given that I just quoted Luther, I thought I’d share his ancient hymn of Christian comfort, “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God,” performed by HeartSong at Cedarville University. I loved it. I hope it blesses and comforts you today:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.