I’m on vacation right now, and that means I really, really shouldn’t be writing a newsletter. But I sat down to read a book (I’m currently reading the excellent Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I by Alexander Watson) and felt an irresistible compulsion to write. It’s Tuesday! On Tuesday I write a newsletter!

Even worse, I have a topic that’s been on my mind for a long, long time. I’ve been thinking a lot about an old chart. And yes, I know what you’re thinking. Anyone who sits around on vacation thinking about an old chart really needs a vacation. But here we are.

I’ve been extremely interested in why so many Americans can look at each other and ask, with complete sincerity, “What happened to you?” As a lifelong Republican turned independent, I get that question quite a bit. I know that Trump Republicans get that same question from their Never Trump friends. “We used to be so aligned. What happened?”

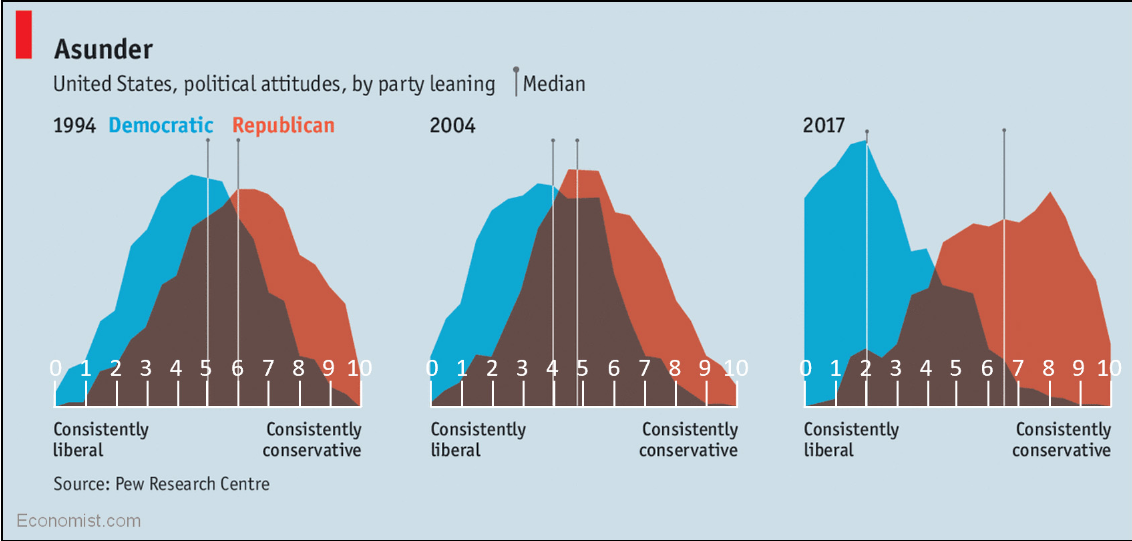

Now, here’s the chart. It’s semi-famous. It’s the foundation of progressive writer Kevin Drum’s argument that liberals are mainly responsible for the culture wars:

The chart is of course a bit out of date, but it still tracks real trends. We know the left has moved left, and for a time right moved right. I’d say the lines are more blurred on the right at the moment because it’s more polarized around a person—Donald Trump—than a series of policies, and locating Trump on a specific ideological spectrum can be difficult.

The chart is also one of the foundations for the argument I made in my book: America’s ideologically moderate middle is vanishing. We possess an “Exhausted Majority,” but that majority is more temperamentally moderate than ideologically moderate.

Indeed, as the group More in Common notes, “most members of the Exhausted Majority aren’t political centrists or moderates.” That’s one reason it’s so difficult to mobilize them as a political constituency. Even if they weren’t “exhausted” (and thus withdrawn from politics), what are the issues that will bring them en masse to the polls?

But I digress. The real reason I’m sharing the chart is to highlight a reality of human nature. More people form their convictions from their communities than form their communities from their convictions. We like to think of ourselves as freestanding critical thinkers who study issues, reach conclusions, and then join parties as a result.

We’re not. Last February, in a piece about conspiracy theories, I talked about Jonathan Haidt’s theory of persuasion he calls the “elephant and the rider.” Here’s how I described it:

The rider “represents your conscious verbal reasoning—the stuff you’re aware of, the stuff that uses logic.” The elephant is “everything else, the automatic processes, the 99 percent of what’s going on in your mind that you’re not aware of.”

Haidt argues that most of us spend our time trying to persuade other people’s “riders.” As he says, we forward them articles with the “seven reasons why you’re wrong,” but the real way to persuade is to “speak to the elephant first.” The elephant, after all, is “much stronger than the rider.” If the elephant digs in its heels, the rider can’t make it go anywhere, but when the elephant moves, the rider will follow along effortlessly.

The red and blue segments of the charts above represent the red and blue elephants, on the move. Those migrations are not the result of millions upon millions of Americans engaging in individualized assessments of the issues and coming to diametrically opposed systems of belief. They’re results of internal arguments, yes, but also of social and cultural forces that impact us in deep and primal ways.

Take, for example, the combination of the Big Sort and the Law of Group Polarization. The Big Sort, the term coined by Bill Bishop in his 2008 book, refers to the increasing tendency of Americans to cluster in like-minded places. The Law of Group Polarization posits that when like-minded individuals gather, they tend to become more extreme. Put those two things together, and you have two groups radicalizing without realizing it, then standing—mouths agape—at their radicalizing opposition and wondering, “What happened to them?”

The answer is clear: The same thing that’s happening to you.

This, incidentally, is one reason we should approach our own politics with an immense amount of humility. I’m not sure we can even begin to know how many of our firm convictions are truly the product of carefully-informed moral reasoning versus the collective will, experience, and relationships of our closest communities.

When we understand this dynamic, we can completely understand, for example, how the small-government constitutional conservatives of the Tea Party (or the House Freedom Caucus) ultimately jumped on the Trump Train. Let’s suppose that you were a 7 or 8 on the chart above before Trump. You were a Republican, yes, but you were also relatively radical. That was your community—millions strong.

Fast forward a few years. If your identity and community were formed around those twin identities—radical and Republican—where do you go? Stand pat, and you’re still a Republican, yes, but you’re suddenly a moderate Republican. A radical Republican will ask, “When did you become establishment?”

But chances are you’re not even asked that question because you’ve moved with your community. The same analysis applies to Democrats as well.

There are always exceptions to these big moves, but it’s not necessarily because those exceptions are the true free-thinkers. If you’re a Never Trump Republican or an anti-woke Democrat, you can’t sneer at others and say, “Look at the sheeple.” Instead, we’re also shaped by our communities and tribes, even if those tribes can feel quite small.

I’m still mad at Jonah for taking the word remnant for his podcast. It’s perfect for describing loss (a remnant obviously used to be part of a much larger whole), hope (biblically, the remnant is the seed of renewal), and community (a band of brothers and sisters). I wonder … how many of us would still be on our present path if we hadn’t found this fellowship? Some of us, certainly. But all of us?

I don’t share any of this to argue we’re nothing more than political pack animals. We’re still responsible for our choices. Instead, it’s to highlight that one of the most important choices we can make in life is choosing which pack we ultimately belong to—and who ultimately has access to our hearts.

Here’s a name every American should remember: George Henry Thomas, the Rock of Chickamauga. Statues of him should cover the South. He should be a symbol of southern heroism and martial valor. He’s a Virginian who made a different choice than Stonewall Jackson or Robert E. Lee. He chose to serve the Union cause, even if it meant being deemed a traitor by members of his own family and even if it meant some of his Union colleagues didn’t fully trust him.

Why did he make such a dramatically different choice? I don’t want to minimize his own personal integrity, but Confederates also blamed his northern-born wife. At the core of his life, in the small tribe of his own family, there was another voice who had a claim on his heart.

Okay, that’s enough for now. While I was typing on Deck Four of the Disney Wonder, sailing through choppy seas on the way to Juneau, Alaska, a dance party broke out. Confetti is falling on my head, “Waka Waka” is blaring from the speakers, and I’ll take that as my cue to leave. Rumor has it a pod of killer whales has been spotted off to port, and as much as I love writing newsletters, that’s a sight I want to see.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.