At the risk of feeling old, earlier today I went to one of those websites that will tell you what percentage of Americans are older and younger than you. I’m 52, and that means more than two-thirds of my fellow citizens are younger. Why does that matter? Well, they can’t relate to the glories of seeing the original Star Wars trilogy in the theaters. They’ve only seen documentaries about the Larry Bird/Magic Johnson rivalry. Oh, and they have absolutely no idea what it’s like to worry about a world war.

I grew up in the Cold War, when bookstores stocked their shelves with books analyzing the balance of military power between NATO and the Warsaw Pact (I owned several), debates about ICBMs and strategic bombers could monopolize public attention, and there were multiple war scares that kept Americans up at night with real fears about catastrophic conflict.

Then, three things happened in rapid succession that dramatically changed the world. In 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, and the Warsaw Pact unraveled. In February 1991, the U.S. and its allies decisively defeated Iraq in the first Gulf War. And that December, the Soviet Union fell. Taken together, these events not only left the world with one global superpower (a “hyperpower” according to some), they established the absolute dominance of American arms.

Since that time America has faced economic shocks, it’s endured a devastating terror attack that led to two long counterinsurgency conflicts, and it’s faced a pandemic. But the world has been mercifully spared even the possibility of the kinds of great power conflicts that could spiral into world war. After all, who would be foolish enough to challenge the United States?

It’s against this backdrop that we can see the triviality of many of our current political arguments as a kind of luxury, a byproduct of peace and global stability. Did we really just spend an entire news cycle arguing about Dr. Seuss? How important, really, is the location of Major League Baseball’s All-Star Game? We certainly do clash over important issues, but the bulk of our energy and anger is consumed in culture war clashes that previous generations would rightly consider inconsequential.

I raise this because I’m increasingly concerned that the old world is coming back. I’m increasingly concerned that the Long Peace might come to an end, and we might all be shocked when it does. We shouldn’t be.

Two things are happening at once that should wake us up to the possibility that the world might change again, as dramatically as it did in 1989 and 1991—but with far more catastrophic consequences. First, American military hegemony is in doubt. Yes, we still have the world’s strongest military, but our qualitative advantage is decreasing, and we face the possibility of actually losing a war.

Second, our enemies are increasingly aware that they’re closing the gap and are now, today, engaged in dangerous and provocative actions overseas. We might find ourselves quickly facing the most serious foreign policy crises in a generation, in Ukraine, Taiwan, or both.

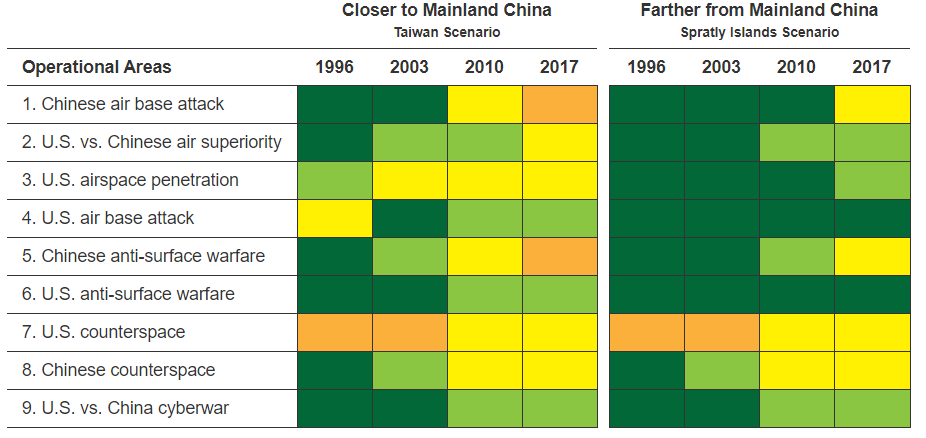

Let’s first deal with the closing military gap. Here’s a graphical representation of the shrinking American advantage over China, taken from the RAND Corporation. The short way of understanding it is that dark green is good. It represents American military advantage. Orange and yellow are bad:

And that picture hasn’t necessarily improved since 2017. War games look increasingly grim:

In simulated combat in which China attempts to invade Taiwan, the results are sobering and the United States often loses, said David Ochmanek, a former senior Defense Department official who helps run war games for the Pentagon at the RAND Corp. think tank.

More:

In tabletop exercises with America as the “blue team” facing off against a “red team” resembling China, Taiwan’s air force is wiped out within minutes, U.S. air bases across the Pacific come under attack, and American warships and aircraft are held at bay by the long reach of China’s vast missile arsenal, he said.

“Even when the blue teams in our simulations and war games intervened in a determined way, they don’t always succeed in defeating the invasion,” Ochmanek said.

Why is this relevant? As our Morning Dispatch crew covered today, China is engaged in escalating dangerous provocations near Taiwan, dispatching ever-larger numbers of fighters and nuclear-capable bombers to Taiwanese airspace. In a smart and ominous editorial, my former colleagues at National Review warned that a “Chinese attack on Taiwan is getting closer.” No, they don’t argue that war is imminent, but as the military gap closes, the determination to take Taiwan persists:

Underlying the Chinese push for a military edge is a relentless national determination. “Reunifying” the island with the mainland has long been understood to be a core interest of the party-state and a matter of regime survival. Xi Jinping is believed by U.S. officials to view reunification as key to cementing his rule.

The alarms aren’t just coming from conservatives. Last week an Associated Press report noted that the American military believes “China is probably accelerating its timetable for capturing control of Taiwan.”

At the exact same time that China is increasing its provocations near Taiwan, Russia is engaged in a massive buildup of forces outside Ukraine. In fact, the size of the buildup (approximately 80,000 troops) matches a war scenario recently imagined by RAND. In a move reminiscent of the Cold War, President Biden has proposed a summit with Russia to reduce tensions.

How strong is Russia? So near its own borders, the answer is clear: very strong. One of my first French Press newsletters took a close look at Russian military capabilities and came to a sobering conclusion: NATO’s combined European forces could not defeat Russian forces close to its borders, and any reversal of Russian gains would require massive reinforcement from the American mainland. Russia can execute a “smash-and-grab” operation and dare the West to stop it.

I interviewed RAND scholar Brian Nichiporuk, and while he focused on an attack on the Baltics, much of the same reasoning applies to Ukraine:

Yes, Russia has emphasized a formidable defense, but the “capabilities Russia has pursued [also] gives them substantial offensive capability against states along Russia’s borders. Put another way, Russia is entirely capable of what Nichiporuk called “smash and grab” operation in the Baltic states. It could seize, say, Estonia, immediately incorporate it into Russia’s extremely capable defense umbrella, and then present the western alliance with a “fait accompli” that unless undone could very well break NATO.

None of this is news for anyone who’s paid attention. To deter Russia, NATO has modestly reinforced Estonia, but not at a level sufficient to truly protect the nation—a deployment that large would almost certainly provoke an extreme Russian reaction. But what was interesting to me was Nichiporuk’s concern that if Russia seized one or more Baltic states, that NATO had insufficient force in Europe to reverse Russian aggression. In other words, absent large-scale American reinforcement from home (into what would be a brutal battle space), Russia could fend off NATO.

This is what is meant by the “fait accompli.” Russia is formidable enough to make American politicians (and likely the American public) ask themselves whether intervention is worth the considerable casualties and the potential dreadful setbacks.

To be clear, unlike an attack on a NATO member state like Estonia, neither an invasion of Ukraine nor an attack on Taiwan requires an American military response. No defense treaty compels an American defense. In fact, I’d be surprised if the U.S. fought for Ukraine. But history teaches us that large-scale combat has unpredictable consequences. It’s fair to say that when Austria-Hungary invaded Serbia in 1914, few Americans imagined that they were less than three years away from a national mobilization and trench warfare in France.

Taiwan is a different story. While we’re not bound to defend Taiwan, we’ve long planned to come to its aid, and an attack on Taiwan would almost certainly draw American forces into battle. That’s why a Taiwan conflict seems less likely in the short run than serious conflict in Ukraine. But “less likely” is a long, long way from impossible, and smart observers are sounding alarms about the possibility of a potential double emergency:

I hope I’m being alarmist. It’s infinitely preferable to engage in Twitter wars over Dr. Seuss and diversity training than it is to be shocked at the news that an American carrier is in flames off the coast of Taiwan. But it’s a simple fact that America is turning inward while our geopolitical rivals have closed the military gap and remain laser-focused on their own national interests.

Our commitment to our international alliances wanes. Our military dominance diminishes. Our nation divides. We are still very strong, but we are no longer invincible. And that means we’re entering a period of risk of Great Power conflict arguably unlike any we’ve experienced in more than a generation.

The title of this essay asks if we’re living in a 9/10 moment—that period of calm before the unexpected, shattering 9/11 storm. We can hope not, but for the first time in a long time, we simply can’t be sure.

One more thing …

Ok, that was a lot to think about. Let’s lighten the mood a bit. Yesterday Sarah and I brought David Lat from Original Jurisdiction on our podcast to talk about Justice Breyer, court packing, and religious liberty. It was a great conversation, and David was a delightful guest. Enjoy:

One last thing …

Americans have largely forgotten the fears that preceded the first Gulf War. Most of us had absolutely no idea that the fight would be so lopsided, that our forces were so proficient, and that our weapons were vastly superior to the Soviet weaponry Iraq deployed. This short Operations Room documentary details arguably the most significant battle of the conflict. I served with men who served at 73 Easting, the “last great tank battle of the 20th century.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.