One of the most frustrating aspects of the online debate about coronavirus is the ongoing idea that we confront some kind of stark binary—that we can have a lower number of deaths and a dreadful recession or our government can tolerate a higher level of risk and “open up” the American economy, thereby avoiding most of the economic pain. In reality, our national challenge is almost fiendishly complex. Human behavior, urban/rural economic disparities, international trade, and federalism all combine to mean there is no either/or, but rather a series of both/ands that ultimately require that we keep the virus under control.

Interestingly enough, this either/or conversation is taking place—especially in conservative Twitter and on conservative media—just as coronavirus deaths are spiking to almost 2,000 per day in the United States, with the state of New York now facing more confirmed cases and deaths on a per capita basis than the worst-hit European nations of France and Spain.

In spite of this sobering death toll, the immediate impetus behind the new call to “open up” America (a call that in some quarters is quite militant) is the continued downward revision in estimated COVID-19 deaths (assuming social distancing) in the influential Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) model combined with the undeniably dreadful unemployment numbers—numbers that represent a heartbreaking burden on American families.

But even as we cheer the downward projections in total deaths and lament increasing American unemployment, the question still remains: Is it even possible to restore the economy before the virus is brought under control? Let’s walk through some key factors.

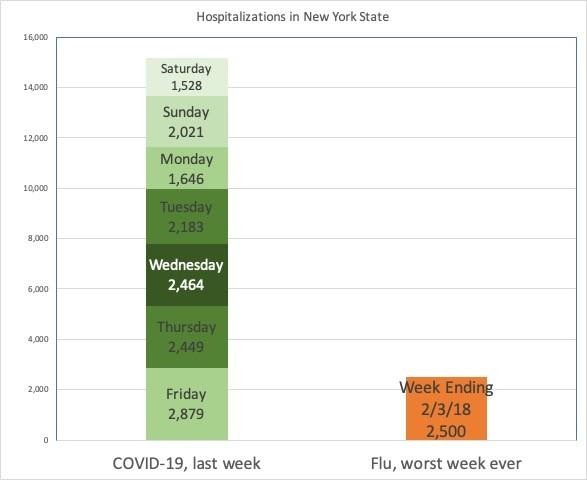

First, evidence continues to accumulate that coronavirus is extraordinarily dangerous. It is no flu. Over at the Washington Examiner, Timothy Carney has been doing yeoman’s work looking at the best available hard numbers (not models) regarding the severity of COVID-19. Take a look at this chart, comparing coronavirus hospitalizations with flu hospitalizations in New York:

Next, as Carney notes, in normal conditions, 145 New York City residents die per day. In the first five days of April, 200 people died per day from COVID-19 alone. Moreover, while one can argue about the “true” cause of death when COVID-19 afflicts a vulnerable person, increased overall mortality creates its own compelling argument. Or, as the headline of one of Carney’s pieces succinctly puts it, “Cause of death is a tricky concept. A lot more people dying isn’t.”

And while our testing regime is still inadequate and certainly undercounting COVID-19 cases (and also potentially undercounting deaths), it is worth noting that as we’ve increased testing, the death rate from COVID-19 has increased, not decreased. As of the time of writing, it stands at 3.55 percent of confirmed American cases—roughly 35 times greater than the death rate for the flu. That number should go down (and I expect it to go down). But so far it hasn’t.

Second, regardless of the state of the law, perception of danger influences human behavior. One of the most interesting aspects of Jonah’s fascinating Remnant podcast interview with Lyman Stone was his description of why places like Hong Kong, Taiwan, and South Korea reacted so effectively (at least so far) to COVID-19 even though they took different approaches. I don’t want to oversimplify his point, but accurate information about the threat of a virus—combined with their bitter experience with SARS—empowered their effective response. Both governments and people reacted rapidly and effectively to a perceived threat.

Why does this matter for our economy? Simply put, you could end the state-imposed lockdowns tomorrow, and tens of millions of Americans who now accurately perceive the danger of the virus—especially in America’s dense urban areas—simply will not resume normal economic activity. And I’d submit that those least likely to resume normal economic activity will be the kinds of high-income, high-information individuals who have disproportionate economic power. If people are dying and falling ill at high rates, Americans will be cautious, no matter what a governor or mayor says about the danger.

To make this concrete, Bill de Blasio’s earlier careless bravado has not been vindicated. San Francisco Mayor London Breed’s caution has:

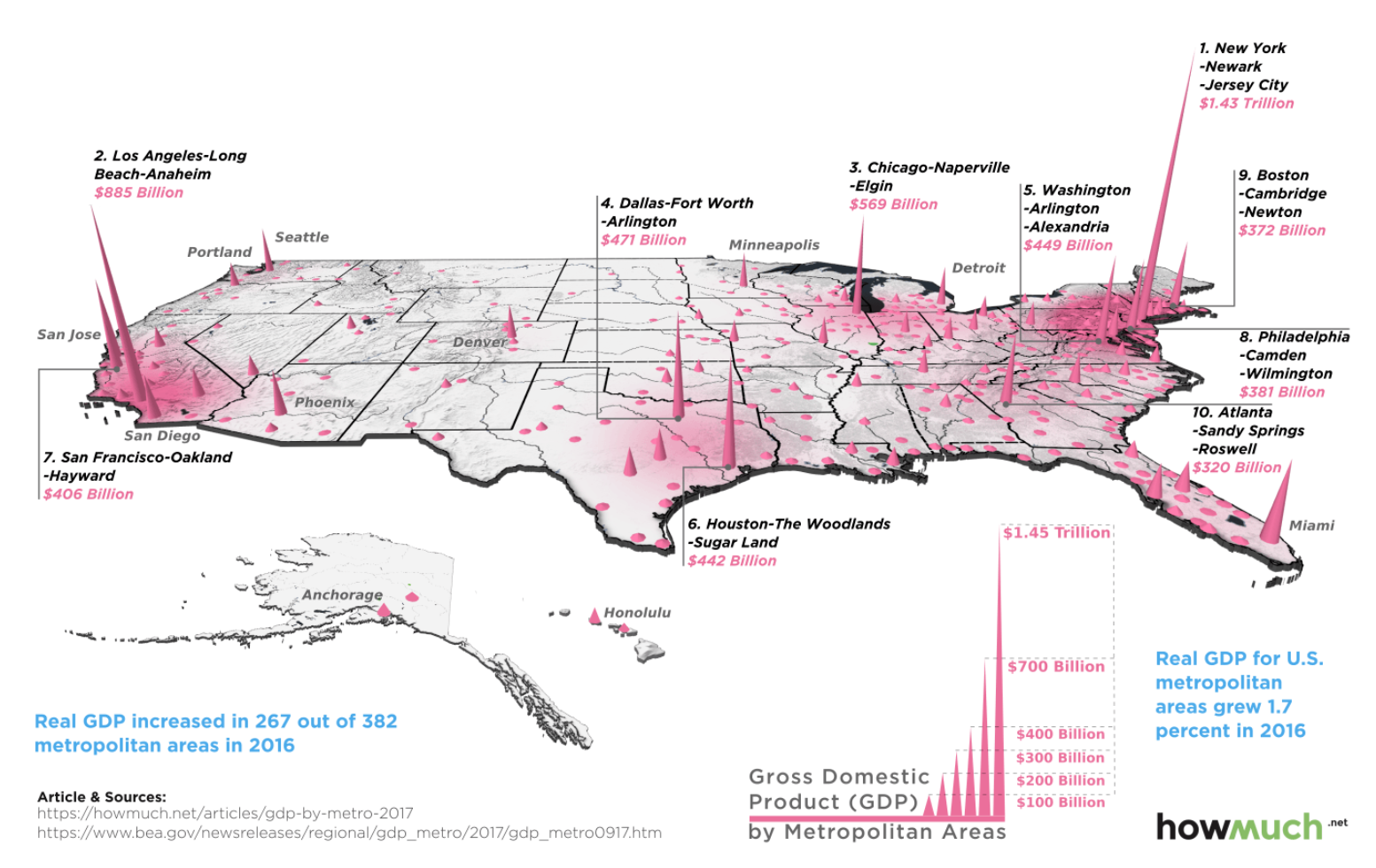

Third, the American economy can’t be healthy unless its cities are healthy. New York City is a terrifying cautionary tale. Does anyone think that city is prepared to “open up”? Does any rational mayor of a dense American city want to risk New York’s fate? And if you think the American economy can snap back to health without its urban centers back online, think again. The map below, which measures American economic might by metropolitan area, is telling:

America’s cities represent the core of the American economic engine. Bitter domestic and international experience teaches us that densely packed cities (while not the only vulnerable communities) are among the most vulnerable to the spread of the virus. Church services, funerals, and tourist travel can certainly cause flare-ups even in rural locations, but no one should doubt the ability of the virus to spread with deadly speed in our most economically vital communities.

Fourth, the American economy can’t be healthy when our trading partners are on their knees. The United States is the largest exporter and importer of goods in the world. International trade supports an estimated 39 million American jobs. Oh, and the vast majority of the top 20 economies in the world are facing their own coronavirus challenges, including lockdowns and—in some instances—waves of coronavirus deaths at per capita rates that would shock the American conscience.

For example, the Spanish death toll is akin to 90,000 Americans dying in a single month. The Italian death toll is similar. If we suffered the same rate of death as France, then 60,000 Americans would have died in four weeks. The United Kingdom has suffered the equivalent of 35,000 Americans dying in three weeks. These nations have large economies. They are important American trading partners. They’re on their knees as well.

Finally, it’s worth saying this again and again—there is no single government official who has the power to “open up” America. I’ve explained this at length before, but Donald Trump could decide tomorrow that the time has come to bring the economy back, and he could not unilaterally order any single governor or mayor to end a shelter-in-place order. The federal government does not presently possess that authority over the states. Mayors and governors have primary authority over public health in their jurisdictions.

That means that mayors and governors will likely open up at different rates, based on local conditions, and the larger the city, the more wary they will be of replicating the New York disaster.

Why go through all this? It’s simple. Even though models have been revised downward, “not as terrible as we feared” is not the same thing as saying, “not terrible.” And because the disease is dreadful—and because it is obviously taking a high toll in those jurisdictions where it has truly spread—every talking head or tweeter who is claiming that we can somehow bring back the economy before we get a better hold on the virus itself is spreading misinformation. People will not behave the same, our cities will not snap back to life, our trading partners won’t revive themselves, and our governors and mayors won’t risk becoming Bill de Blasio, the sequel.

One last thing …

I’m still fully down the sports YouTube rabbit hole, and I was recently reminded of the second great battle of good and evil in the 1980s. The first, of course, was NATO vs. the Warsaw Pact, and that ended with the triumph of good when the Berlin Wall fell. The second epic conflict was between the Lakers and the Celtics, and if you wonder which side was good, all you need to do is watch this old clip of perhaps the greatest and most egregious atrocity in modern sports history.

Readers, in the comments tell me—on a scale of 1 to 10, how villainous were the Celtics: 9, 9.5, or 10?

Photograph of a mural in Los Angeles by Apu Gomes/AFP/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.