If you know anything about American Evangelical higher education, the shocking thing about the board of trustees’ decision to place Liberty University president Jerry Falwell on an “indefinite” leave of absence isn’t that it happened, but that it took so long. And no, I’m not naïve. I know full well that Evangelical educational institutions have often suffered from low-integrity leadership in the past. But the general rule has been clear—misdeeds must be done in secret for the leader to survive. He must conceal his sin. The instant his wrongdoing becomes open and notorious, the leader must leave.

Jerry Falwell, however, was blazing a new trail. He was living his sin out loud, careening from controversy to controversy even as his students and faculty lived under the traditional, strict moral rules of Christian education. In response, Falwell didn’t bother pretending to be a spiritual leader. Instead, his argument was the higher education equivalent of “scoreboard!” His success excused his sin.

Make no mistake. Those are impressive stats, the envy of countless Christian college presidents. But these presidents—including men I know—without fail believe their highest calling isn’t raising money or building an athletic program, but rather demonstrating (as best they can) Christlike servant leadership for students, faculty, and staff and preserving the spiritual integrity of their institutions from the top-down.

They understand that in God’s economy, faithfulness trumps endowment.

But for too long, in Liberty’s economy, that priority was in doubt. To be clear, thousands of members of the Liberty community were living faithful lives. But the person at the pinnacle of the university found himself lurching from scandal to scandal.

It’s easy to get inoculated against outrageous public conduct in the age of Trump, but even by the new standards, Falwell’s public conduct was simply extraordinary for a Christian leader.

He was placed on leave after he briefly posted a picture with a woman he said was his wife’s assistant. Their pants were unzipped, and he appeared to be holding an alcoholic beverage (though he denied it). He then conducted a truly bizarre short interview apologizing and promising to be a “good boy.” He slurred his words. He sounded drunk. You can see the picture (and hear the interview) below:

But this is the tip of the iceberg of outrage and sometimes outright weirdness from Falwell. I could spend the rest of the newsletter detailing his various scandals, but I can recommend this comprehensive report from Brandon Ambrosino at Politico, detailing Liberty’s culture of fear and Falwell’s pattern of self-dealing, and two short summaries–one from Ruth Graham at Slate, and the other from former Liberty student Calum Best at The Bulwark. And then there is the lingering, incredibly strange controversy surrounding Falwell, Trump’s former lawyer Michael Cohen, a pool boy, and alleged racy photographs of Falwell’s wife:

Mr. Falwell — who is not a minister and spent years as a lawyer and real estate developer — said his endorsement was based on Mr. Trump’s business experience and leadership qualities. A person close to Mr. Falwell said he made his decision after “consultation with other individuals whose opinions he respects.” But a far more complicated narrative is emerging about the behind-the-scenes maneuvering in the months before that important endorsement.

That backstory, in true Trump-tabloid fashion, features the friendship between Mr. Falwell, his wife and a former pool attendant at the Fontainebleau hotel in Miami Beach; the family’s investment in a gay-friendly youth hostel; purported sexually revealing photographs involving the Falwells; and an attempted hush-money arrangement engineered by the president’s former fixer, Michael Cohen.

I’ve spent my entire life in American fundamentalism and evangelicalism. I attended an Evangelical college (and loved it), and I’ve worked for Evangelical institutions. There is one thing you’ll always find—a tension between the incredible aspirational ideals of Christian behavior and the messy sinfulness of all men, including Christians. We aspire to holiness, yet we can never come close to perfection

In high-functioning Christian organizations, the institution attempts to resolve that tension by defaulting toward seeking to uphold the aspirations—and the higher the position and the greater the responsibility, the more the aspiration controls. There are higher expectations for presidents than members of the faculty, and members of the faculty live with greater expectations than students.

This pattern has biblical roots. Elders—those who govern the church—must possess greater minimum qualifications than deacons, those who are more apt to manage the logistics of the church. Indeed, this pattern is so deeply ingrained that low-functioning Christian organizations will often go to great lengths to maintain the trappings or appearance of executive integrity. They know the instant the con is truly exposed, the leader falls.

For several years, however, Liberty flipped this script. The president lived life with greater freedom than his students or his faculty. The message sent was distinctly unbiblical—that some Christian leaders can discard integrity provided their other qualifications, from family name to fund-raising prowess, provided sufficient additional benefit.

In this way, Falwell functioned as an uncanny Evangelical mini-me to President Trump and served as a symbol of the extent to which the spirit of Trumpism could leak into important Evangelical institutions. Like Trump, Falwell inherited a portion of his father’s empire. Like Trump, Falwell was a roguish departure from the more-dignified norms set by their predecessors. Like Trump, Falwell’s scandals and outrages multiplied right alongside a measurable record of accomplishment.

In fact, for a time it seemed that—like Trump—Falwell prospered not in spite of his outrageous conduct, but because he disregarded norms. As with many of Trump’s most prominent Evangelical defenders, his gleeful defense of the president—and his own imitations of Trump’s combative style—gained him more power and more prominence. Compromise often carried with it an immediate benefit. Take this anecdote, from a Ringer profile of Falwell’s attempts to transform Liberty into a football powerhouse:

“I’ll tell you a funny story,” Jerry Falwell Jr. says.

It’s about his school, Liberty University, and about its football team, the Flames, and about his friend, the most powerful man in the world. “My wife and I attend a lot of Friday-night dinners with recruits,” says Falwell, the president of Liberty, the conservative Southern Baptist university that ascended in 2018 from FCS to FBS football and will play in its first-ever bowl game this Saturday. We’re talking last August, a few days before Liberty’s first FBS game.

“We’re sitting around a table like this one,” Falwell continues, gesturing to our table in a conference room high above Liberty’s Lynchburg, Virginia, campus. “It’s me and my wife, and it’s the recruit’s father and his son, who’s a running back.”

He leans forward. He has a gray beard, blue eyes, and a charmed bluster. He smiles. The story is just getting good. “And then my phone rings,” he says. “It’s an unknown number. And I answered it.” His eyes brighten.

“It was the president.”

The president of the United States was calling Falwell to congratulate him on a CNN appearance. That’s access. That’s a measure of success.

But isn’t this the same with virtually every temptation and moral failure? There is an immediate reward to sin. The drug addict gets his high. The adulterer has the sex he wants. The con man makes his money. The abuser achieves domination over his victim.

It is thus strange to watch political Christians exulting in the short-term fruits of their manifold moral compromises. Yes, we know that sin has its benefits. Otherwise there would be no temptation.

Yet there is no avoiding the ultimate consequences. As with Trump, there are signs that character is, in fact, destiny. No, Falwell isn’t facing anything like the academic equivalent of the death toll, economic ruin, and social upheaval that’s now occurring on Trump’s watch, but beneath Liberty’s gleaming exterior, there are signs of trouble.

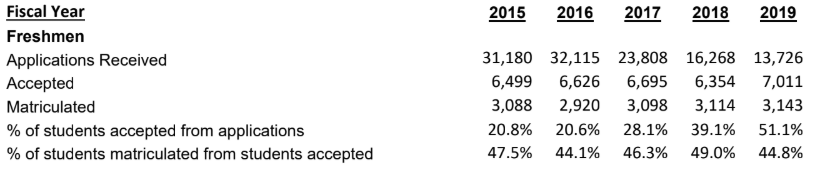

In fact, if you’re an academic, you’ll recognize the significance of numbers like these. Here is the shocking decline in Liberty’s freshman applications:

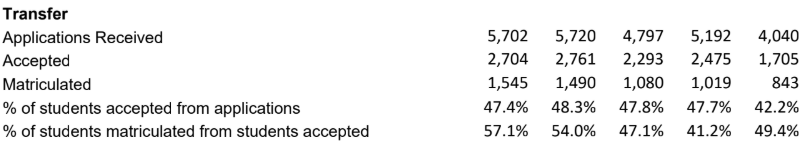

Transfer applications declined significantly as well:

Liberty’s vaunted online program declined by almost 10 percent between 2014 and 2018 before surging back in 2019. And the campus was rocked by the recent departure of high-profile black athletes, setting back Falwell’s dream to become the Notre Dame of Evangelical sports.

Yes, Liberty is still wealthy—wealthy enough to spend millions of dollars sponsoring one of its students in NASCAR—but Liberty is relearning an old lesson. Money is not the only (or main) metric of academic success. It’s certainly not the main metric of Christian academic success.

But here’s the good news. The university’s Christian conscience is awakening. Many of its students and professors have recoiled in shame and horror at the conduct of their president and grieve for the reputation of their institution. Last week even Falwell’s friends on his previously loyal board have said, “Enough.”

Enough for now, at least. We don’t know the length of Falwell’s “indefinite” leave. And we don’t know if Falwell’s own Christian conscience will awaken. We can pray that it will. But I know enough about Liberty to know that there is a deep well of faith at that school. And now there is an opportunity for a new beginning.

It is part of the majestic grace of Jesus Christ that those new beginnings can be glorious. They can eclipse the pain and shame of the past. Beauty can come from ashes. One of the most reassuring and mysterious verses in the Bible is Romans 8:28: “We know that all things work together for the good of those who love God, who are called according to his purpose.” Liberty University is chock full of thousands of men and women who love God and are called to serve him. Goodness awaits.

One last thing …

In the last few weeks, hundreds of thousands of readers have come to this Sunday newsletter for the first time, and many of them probably wondered why I’ve attached a YouTube at the end of each one. I love Christian music—especially praise music—and I do it to add a dash of encouragement after writing about often tough and painful subjects.

I’m ending with this song for three reasons. First, it’s a song of true gospel deliverance. Second, I love Brooke Ligertwood’s voice. And third, the tens of thousands of young arms raised in worship at the Passion conference serve as a sign of hope and promise. There is a generation of young Christians—at Liberty and elsewhere—who love God and need good shepherds. It’s my generation’s sacred obligation not to fail in that most vital task.

Photograph by Alex Wong/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.