I’m going to start with a story I shared yesterday in our new Good Faith podcast. When I served in Iraq my primary job function was something called “operational law.” Think of it as the law of war concretely applied to rules of engagement decisions (“can we bomb this target?”) and detainee operations. My secondary function was military justice, assisting the command in maintaining military discipline.

But I had a third function as well, legal assistance. I was the only lawyer in a combat arms unit of almost 1,000 men in an isolated base miles from any external support. So I put out the word—I’ve got an open door. Come to me if you’ve got questions about anything even tangentially related to law, especially if it involves your family.

This is where you learn that the costs of a deployment extend beyond the fear, the stress, the wounds, and the grief of losing brothers. I can’t forget their stories.

There was the soldier who returned home on mid-tour leave and was greeted in the airport by his wife, his son … and his wife’s new boyfriend.

There was the cavalry scout who ran into my office frantically worried that his girlfriend’s estranged husband was about to hurt or kill the soldier and his girlfriend’s newborn son (yes, the situation was that sad and complicated).

There was the soldier who wondered if he could get a long-distance divorce when he learned his wife started stripping and wondered if he’d lose custody of his child when he returned home.

Time and again I was exposed not just to shattered families, but to the consequences that extend when grandparents aren’t together, and neither are aunts and uncles. An extended family can absorb a divorce or two. It can extend its arms and take care of a single mom. But what happens if the entire family tree is fractured, up and down the line?

I thought of these guys—of these families—earlier this week when the American Enterprise Institute’s Survey Center on American Life released new information indicating that America’s class divide is also a loneliness divide. It’s a friendship divide. It’s a fellowship divide. It’s a religious divide.

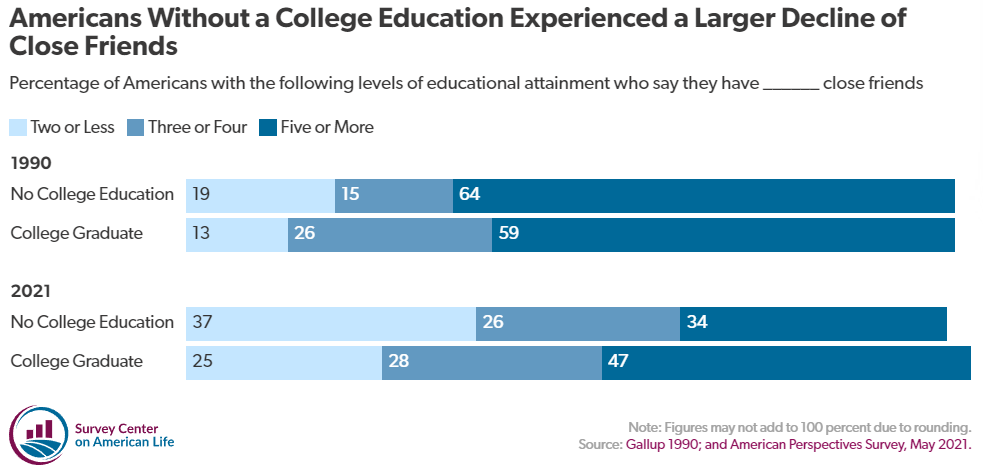

To boil down the findings to their essence, America’s less-educated, working-class citizens have fewer friends, engage with their communities less, have less-stable families, and participate in religious life less than their college-educated peers. Look at these numbers—first, here are the diminishing friendships:

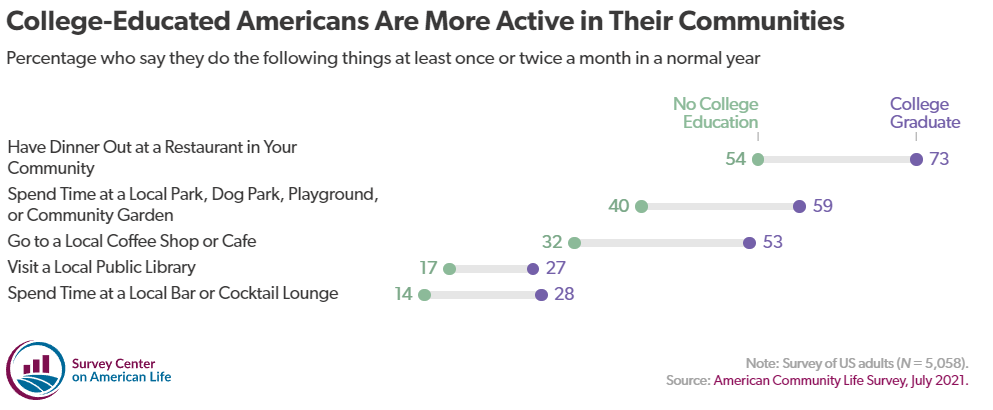

Next, here’s the difference civic and community engagement:

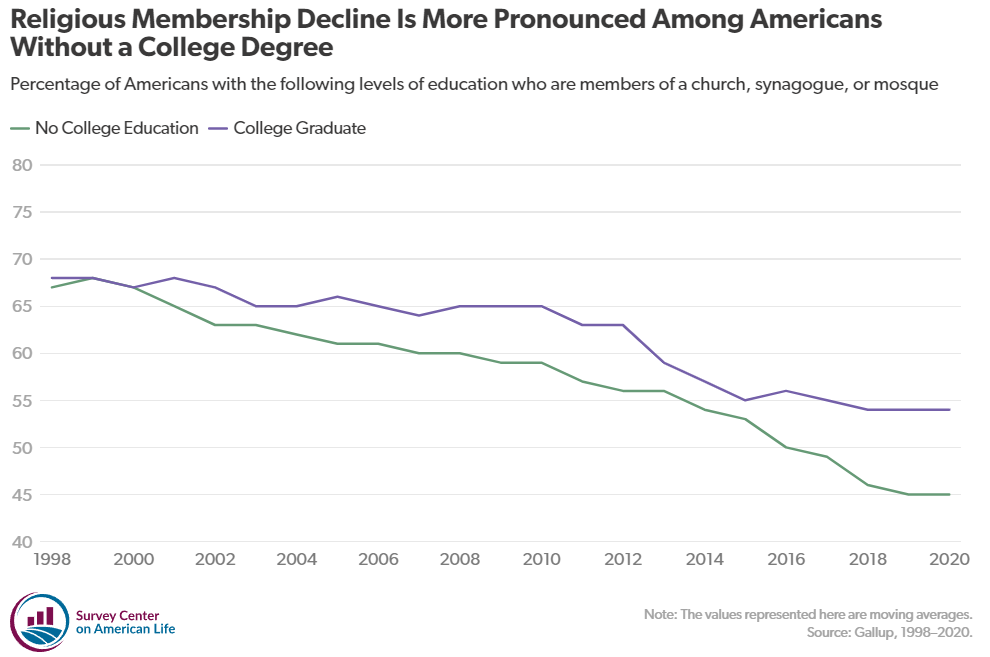

And, finally, here’s the difference in religious participation:

And if you want to see an even more heartbreaking graphic, let me share one I’ve shared before. Look at the breathtaking disparity in opioid deaths between men and women, between the college-educated and those without a degree, and between married and single:

At the risk of talking myself right out of a job (I am a pundit, after all) might I suggest that our nation’s increasing political zeal is fundamentally misplaced? Could I suggest that as religious and civic engagement declines, too many Americans are replacing religion with politics, and the false god of politics does not present the answer for what ails our hurting nation?

Don’t mistake me, I’m not arguing at all that politics does not matter. Justice matters a great deal, and a nation can and must do what it can to (at the very least) ensure that its institutions aren’t obstacles to human flourishing and to creatively seek ways to increase opportunity for all its citizens.

But when we speak of our own energy and our own efforts, here’s a basic truth. We can have a large amount of influence over a small number of people and a small amount of influence over a large number of people. The question that can and should challenge so many of us—especially those most engaged in politics—is whether our efforts are calibrated to our impact.

In a democracy, an informed and engaged citizenry is an important measure of national health, but—at the same time—the concrete consequences of our political engagement (much less the emotional or intellectual energy we expend on pondering that engagement) can’t be measured on an electron microscope compared to the consequences of our presence in our neighbors’ lives.

And yet, despite the obvious reality that our political engagement is less relevant to the real world than our personal interventions, all too many of us increasingly obsess over politics. There’s a very human reason for this—compared to virtue in real life, virtue in politics is easy. Compared to love in real life, love in politics is also easy.

By Facebooking about the right policies or Tweeting about the right candidates, we can, for example, serve the homeless from a distance. We can exalt the virtues of the working class without actually knowing the working class. Even our donation dollars—as valuable as they are—can permit us to keep human pain at arm’s length.

Charts and numbers, like the charts and numbers above, can help us understand the scale of a problem. They help us understand that sometimes the things we observe and experience don’t reflect a larger reality, but sometimes they do. And when we see loneliness and hopelessness around us, we’re seeing a malady that afflicts millions.

What is to be done? My friend and podcast co-host Curtis Chang talks about hope as “locating oneself within a larger story, specifically a story that has a past that fills us with longing, a future that pays off on that longing, and then a present that engages our energies.” To be hopeful, he says, is to “inhabit this story, especially with others who share this story.”

Think of that definition in the classic context of nuclear and extended families. There is a longing for love—the love of a spouse, the love for children. There are present energies expended to first find, then nurture and sustain relationships. And then there’s the future vision—of children fully grown, loving their own spouses and having their own children.

To return to the military context at the start of this essay, I’m convinced that one of the prime reasons for veteran suicides and veteran despair is that when a soldier leaves the service, he or she is often ripped out of the military’s own unique narrative—a past, present, and future that provides its members with a unique sense of purpose and, yes, of hope.

I’ll never forget what one of my friends told me shortly after we got home. “I’m not even 30,” he said, “And I think I’ve already done the most significant things I’ll ever do in my life.”

Think of the loss of that past, present, future narrative when a family fractures, or when a friendship ends, or when a factory closes. Longings are unfulfilled. Present energies feel wasted. Future hopes fade.

This is where the church itself, because it is a family, and because it is a fundamental part not just of a story of hope, but the story of hope, is indispensable and irreplaceable. And the Advent season makes that story all quite real. There is a concrete connection with a deep past, a child whose birth was foretold from the beginning who provides the vision of a world repaired, of hurts healed.

There is a present purpose that engages our energies—the effort to know and (as much as our fallen natures permit) imitate the character and nature of that child made into a man.

The future hope blazes brightly, and it’s not “just” a hope of eternity—an indeterminate future point when creation is made new—but the assurance that we are being presently transformed, from the inside out, not for the “good life” of ease and comfort but for a life of Godly purpose, even though that life can be hard indeed.

And, finally, one of the great gifts of a functioning church is that you do in fact share the story with others. You do not walk alone.

With that hope as a contrast, politics rightly seems small and weak, even though it does contain its own causes and narratives. The thrill of political combat or the hope of an inspiring campaign can provide a sense of purpose, but it’s a thin gruel compared to the holistic impact of a loving family, of deep friendships, and of a healthy church.

Given that contrast, It’s senseless to end a friendship or fracture a family because your opinion about matters you don’t control conflicts with my opinion about matters I don’t control. And to use those differences as pretexts to engage in the kind of interpersonal conduct that really matters—to insult, to threaten, to inflict emotional wounds, to isolate, to deceive, to separate? It staggers the imagination that so many of us have chosen that path.

Again, I’m not saying politics don’t matter. I’m not saying anyone should forsake the public square. But when your neighbors are hurting, understand that so very many are suffering from wounds that politics cannot heal, that even your most fierce convictions shouldn’t stand in the way of grace, and that a lifetime of posting and tweeting is of little consequence compared to the concrete action of reaching out to those who feel so very alone.

A new friend …

My wife inspired this essay. She walks all this talk. And if you doubt it, I’d invite you to read a piece she wrote for the Washington Examiner magazine. It’s about a woman named Kathy, and, well, Kathy didn’t like me very much. She took me to task online. All the time. Here’s how Nancy starts the story:

When [David] posted about the Second Amendment, she accused him of supporting laws that would kill people. When he posted about sexual mores, she mocked his “archaic” beliefs. When he posted about class warfare, she posted, “This is a truly awesome pity party.” When he wrote about faith, she said he “pushed God on suffering human beings.” When he wrote about false sex abuse claims, she accused him of promoting “rape apologists.” When he posted against antisemitism, she said he needed to leave that “to people who actually know what it is.” When he expressed pro-life views, she posted about her multiple abortions.

I don’t want to spoil the ending, but it’s marvelous, and Kathy is now a friend. She’s also a Dispatch member (hi Kathy!) If you read anything else this Sunday, please read Nancy’s piece. You’ll be glad you did.

A surprise encounter …

I got up early yesterday morning and drove to Mayfield Kentucky (my wife’s childhood hometown) with two of my closest friends to join a Samaritan’s Purse cleanup team. When we arrived in the tornado-damaged town, I was shocked by what I saw. As terrible as the images of the disaster were online, the real-life view is much worse. The damage was simply staggering, and nothing was more poignant than this scene, a makeshift memorial outside the shattered remains of the Graves County Courthouse:

But hope lives amid the ruins. The Samaritan’s Purse volunteer team was outstanding. Our cleanup team leaders dedicate weeks at a time traveling to disaster sites, organizing makeshift cleanup crews, and ministering to families reeling from unimaginable loss.

I met volunteers from North Dakota, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Missouri, Ohio, Illinois, Tennessee, and Kentucky. Most had decided to help the very moment they saw the wreckage on television. They dropped everything to drive and fly to a town in deep distress. Some had been there for days and planned to stay for days more.

It was a cold, rainy day, but the whole team worked hour after hour without a single request for a break. At roughly 1 p.m., the team leader asked us to stop for a bit and wait for a “special guest.” Well, who should arrive but Mike and Karen Pence. I’d never met the former vice president before, and I must say that I never expected to meet him soaking wet and covered in mud.

I hung back and watched him talk to the victims and volunteers. He was gracious and kind, and folks were genuinely moved by his presence. He took time to talk to each person and spent the most time with the victims of the storm. He helped out for a few minutes and then drove off to visit a different site. For the folks present, it was a very meaningful surprise.

Please pray for Graves County. It has suffered terrible loss. As we pray, we should also thank God for the ministries and volunteers who are even now swarming all over Mayfield, working day and night for people they’ve never met.

This nation contains some remarkable people. I heard some of their stories today, and they give me hope.

One more thing …

I hesitate to give readers too many assignments, but this week’s Good Faith podcast dives into loneliness and hope, but it also dives into a bit of an online dispute about my essay last week. Is it wrong to talk about “white Evangelicals” as a group? Is that unfair? Am I exacerbating our divides and contributing to a tribalism problem I’m trying to help solve?

Also, for the new year we’re going to start introducing conversations with guests. Who would you like to hear from? Let me know in the comments below. And if you haven’t listened to the pod yet, please give it a try.

One last thing …

This isn’t exactly a Christmas song, but it is new this fall, and I love it. It’s about return, recommitment, and renewal. Enjoy:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.