Before I begin, I promise you that you’ll want to click on the YouTube video at the end. It’s an integral part of this newsletter, and you’ll see why. I promise you won’t be disappointed. Now, on to the main event …

How many of you—before posting your political, religious, or cultural thoughts on Facebook—take a deep breath and ask yourself, “Is it worth it?” Some of you may ask that question because you worry about an employer. Will there be issues in the workplace if people find out that you’re a pro-life conservative? That’s certainly a real phenomenon, especially if you work in parts of higher education or parts of Silicon Valley.

But I’d bet real money that even more of you who ask, “Is it worth it?” do so not because of job concerns but because of social concerns—specifically, social media concerns. You’re going to trigger a fight, the fight is going to get nasty, and you just don’t know if some of your friendships can absorb yet another online blow.

Or perhaps you’re fortunate, and your Facebook page has been an oasis thus far. But you’ve got eyes. You’ve seen your friends’ feeds degenerate into screaming matches. Your neighborhood Nextdoor page is full of arguments about masks or perhaps something as mundane as an ALL CAPS fight about teenagers speeding through residential streets. And so you post pictures of your kids or grandkids, take photos of sunsets, and vow to never, ever say the name “Trump” unless you know you’re in a safe social space.

I bring up this daily reality because the more we learn about America’s culture of free speech, the more we understand three interlocking facts:

1. A very small number of people face formal workplace reprisals for their speech (the “cancel culture” that gains so much attention, including from me);

2. A very large number of people engage freely online, on virtually every conceivable platform, and many of them do so with unrestrained fury and vitriol—on issues large and small;

3. An even larger number of Americans now explicitly admit to self-censoring—they do not feel as free to speak their minds as they used to.

The sources for the first two of my claims are experiential and obvious. Cancel culture is real, but in a nation of more than 300 million people, the number of individuals who are truly losing their jobs because of their speech is minuscule and mainly concentrated in elite sectors of the American information economy. Yes, there are some “regular folks” who get caught up in shame storms (for some terrible examples, read this story by my friend Yascha Mounk), but those who get “canceled” tend to be those with existing public platforms.

As for my second point, just open Twitter or Reddit or go to any political Facebook page and dive down into the replies, comments, and mentions. Thousands upon thousands upon thousands of Americans are busy interacting with each other in the least charitable, most hostile ways—subject only to the most haphazard and spotty content moderation.

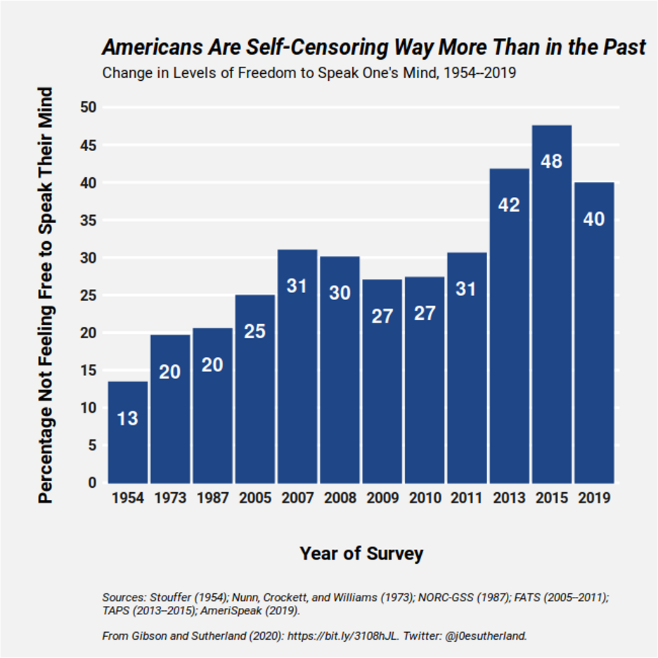

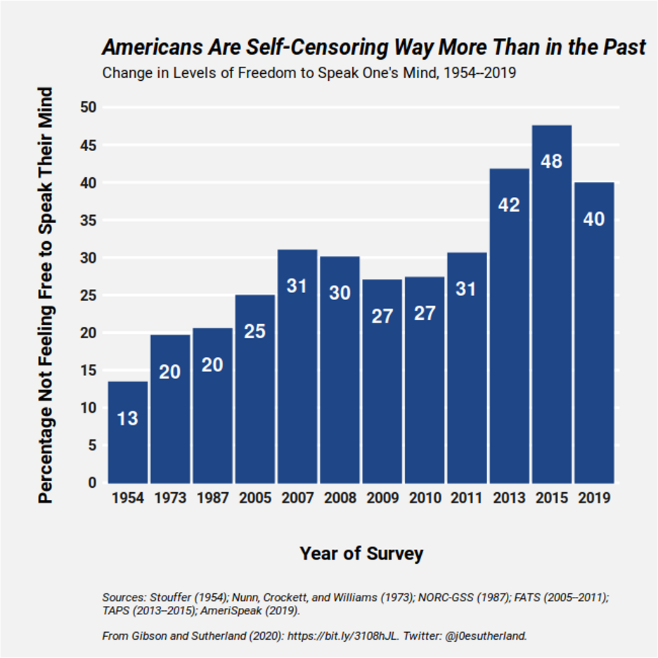

But what about my third point? Here we have some actual social science. Writing in Persuasion, Washington University professor James Gibson and analytics executive Joseph Sutherland summarized the results of their study showing that roughly 40 percent of Americans engaged in self-censorship. That number has risen steadily through the decades, peaking at almost 50 percent in 2015, and is now roughly triple what it was during the height of the McCarthy era:

But Gibson and Sutherland didn’t just disclose the fact of self-censorship. They also looked at the reasons why we refuse to speak, and the reasons are somewhat surprising. While there is a strong relationship between political polarization and self-censorship (in part because of the bitter anger over politics), there appears to be no relationship between the choice to remain silent and the level of “community intolerance.” And there is only a “modest” relationship between “perceived government constraints” and self-censorship.

Interestingly, there is also no indication that those with more “extreme” political views tend to self-censor (hardly surprising considering the exuberant sharing of conspiracy theories online). So what drives censorship? According to Gibson and Sutherland, it’s quite close to home: “[M]icro-environment sentiments—such as worrying that expressing unpopular views will isolate and alienate people from their friends, family, and neighbors—seem to drive self-censorship.”

In other words, despite gallons of partisan ink spilled about what “they” will do to “us,” the real concerns that silence Americans aren’t about an undefined “they” but rather a quite-defined “Uncle Bob” or Jane, your friend from grad school. Of course Bob and Jane aren’t disconnected from national politics or American polarization (hence the study finding a connection between political polarization and self-censorship), but they’re the ones who make the polarization personal.

In fact, the more I look at the reality of American polarization, the more I’m convinced that the national stories are often little more than the fuel for millions of raging personal feuds, and those personal feuds often immiserate us and silence us more than any act of government or story of academic intolerance.

This emphasis on the personal is seen in other reports of America’s political culture, including one of the most important contemporary studies, More in Common’s “Hidden Tribes” survey.

For example, the study demonstrates a high degree of self-censorship on issues such as immigration, race, and LGBT issues and a high degree of concern about causing offense. As the authors note, “Across most segments [of the survey], Americans are highly conscious of the risk of offending other people, and many express anxiety about doing so.” Yet since most Americans don’t have public platforms, where are they experiencing that “risk of offending”?

And so we move where we’re comfortable, to communities of people who are just like us:

I can go miles and miles down this rabbit hole, so let’s go just a bit farther. The findings above remind me of one of the most important concepts for understanding our modern American plight. It explains why the flight to like-minded communities fosters extremism and division.

It’s called “the law of group polarization,” and it originates in a 1999 paper by Cass Sunstein. This “law” is a key aspect of my upcoming book (Plug! Divided We Fall is available for pre-order now), and it holds that, “In a striking empirical regularity, deliberation tends to move groups, and the individuals who compose them, toward a more extreme point in the direction indicated by their own predeliberation judgments.”

In plain English, this means that when like-minded people gather, their views tend to grow more extreme. Each and every “deliberating group”—a Bible study, a faculty, an internet comment board, a collection of Facebook friends—has a “predeliberation tendency.” They have a bias. And what happens with that bias? According to Sunstein, “Members of a deliberating group move toward a more extreme point in whatever direction is indicated by the members’ predeliberation tendency.”

Or, to put it another way, how many of us leave a good Bible study loving Jesus less? How many of us leave an environmentalism conference less concerned about the state of the planet and less motivated to take action to save the Earth?

Sunstein described interesting experiments demonstrating the value of dissent in diluting “group influence.” In certain settings, even the presence of “one compatriot” or “voice of sanity” could make a significant difference, yet the very dynamic of group influence could diminish the likelihood that the “voice of sanity” would emerge. The social costs were too high.

Now, let’s put this all together and tie it up in a bow, and try to describe our real plight:

1. While political polarization is contributing to self-censoring by creating bitter anger over politics, self-censorship isn’t due to a broader “culture of intolerance” but rather to social dynamics very close to home.

2. Instead, we’re self-censoring online, in our families, and in our workplaces for many of the same reasons why we self-censored in the middle-school cafeteria—peer pressure from the people we interact with in our daily lives.

3. As we self-censor, we’re feeding into the perception of unanimity and empowering group influence, thus making it harder for ourselves and others to speak.

Moreover, I’d submit this same dynamic applies not just to our own social circles but also to the famous examples of cancel culture that often make headlines—it’s just that the relevant middle school-cafeteria is the tiny peer group of Manhattan/Washington journalists, or “woke” young adult fiction writers, or the micro-community of the local faculty lounge.

Let me end with one last idea. To break this cycle, we can’t just ask lone individuals to stand up in any given group. How many of us can make a habit of standing alone? No, we have to join the “voice of sanity” as the “one compatriot.” Do not let dissenters twist in the wind—stand up for their dignity when you disagree. Stand up for their argument when you agree. Because we have met the enemies of free speech, and they’re not the distant “other,” but the people in our own social circles who impose a direct and immediate relational cost on those who speak their minds.

One last thing …

Please watch this video. I’m serious. It summarizes the entire newsletter. If you want a humorous visual representation of the incredible social power of the “one compatriot,” please watch this great short YouTube. It’s not the one crazy guy dancing alone at the festival who makes the movement. He can’t do anything without unlocking the awesome power of the “first follower.” Great stuff:

Photograph by Eric Baradat/AFP/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.