Hi,

A bunch of people have asked me what I thought about David French’s New York Times column—“To Save Conservatism from Itself, I Am Voting for Harris”—and the responses to it. I’m going to get there. But I think this is a good opportunity for me to air a larger grievance. (If you don’t want to read that, just scroll down to the “And Now, David” section.)

Here’s a weird confession from someone who has spent a very long time writing and thinking about politics and who loves arguments about politics: I hate arguments about voting. I don’t mean arguments about elections, voter behavior, or even the deep nerdery over the rules and restrictions that should guide how we vote. I mean fights about who I’m going to vote for, or even who you’re going to vote for.

There are few concepts more in need of a thorough demystifying than voting. We project upon it profound meaning and significance. To be clear, I’m not talking about democracy; I’m talking about the individual decision-making process of casting a vote.

A lot of people see voting as a window into your soul. I can’t tell you how many conversations I’ve had with people who think that if you don’t vote for Trump, you are endorsing everything the very worst Democrats want to do—or allegedly want to do. Likewise, there are just as many people who think that if you don’t vote for Harris you are complicit in everything Trump did or might do.

Obviously, there’s some substance to this sort of thinking. I just think there’s much less substance than a lot of people think, particularly very political people. When normal people vote for a politician, I don’t think they feel like they’re responsible for everything that politician does. If the politician fails to follow through, they say “Yeah, I’m not going to vote for that guy again, he turned out to be a real disappointment.”

I think of voting a bit like how I think about prices in a market. The price of a loaf of bread is contingent on a gazillion variables. The cost of all the ingredients, transportation and marketing, the price of competing goods, the weather, taxes, labor costs, and of course profit. Prices change because the variables that go into a price also change. The same goes for voting. Election Day—or the rolling period of weeks or months to account for early voting that ends with Election Day—is a kind of snapshot. Just as the price of bread at the moment you purchase it is the only price that matters, the decision you make when you pull the lever or fill out the ballot is the only “price” that matters in an election.

But once the election is over, your obligation to support that politician is largely over. Elections are the process by which we hire people for defined jobs for a defined period. How they do the job is what matters. How you voted isn’t an identity; it’s a decision you made at a specific moment. I don’t judge people for what they paid for a loaf of bread on a given day. Of course, I make a few more judgments—or at least inferences—about people by how they voted. But not a lot more.

You wouldn’t know it from watching MSNBC, but the people who voted for Trump in November 2020 aren’t responsible for the stuff Trump did in January 2021—because it hadn’t happened yet. The people who backed Trump’s actions after January 6 didn’t do so because they voted for Trump; they did so because they like Trump—which is why they voted for him. People get the causality wrong.

The idea that voting is a window into someone’s soul strikes me as almost a theological heresy and a failure of empathetic imagination. It assumes that the person who voted wrong—or right—sees the world the same way you do and that they invest the same moral, philosophical, and political significance in their vote that you do in yours.

This is not a new thing. I was told by countless people that not voting for Barack Obama or Hillary Clinton could only be explained by racism or sexism. All the other reasons I might oppose a Democrat counted for nothing. At times it was like they believed that I would be fine with single-payer health care (or any other policy position) if the candidate was a white dude.

This sort of thinking stems in part from what you might call “inverse projection”: I am voting for person X for Y reason, therefore if you’re not voting for X it must be because you have the opposite view on Y. The error with inverse projection lies in the fact that voters might not care about Y as much as you do. Or they might care about Z (or H, M, T, and V) more. Sorry for all the algebra. In plain language, I liked the idea of having a black or female president. I just wasn’t so enamored with such things that they trumped everything else I cared about.

The point is that people vote for a perhaps not infinite, but certainly uncountable, number of reasons. Some are not, strictly speaking, rational. And even the rational reasons are often boosted by subconscious tweaks. The fact that height—literally how tall you are—is a statistically significant political advantage is a testament to this. Nobody says, “I’m gonna vote for Smith because he’s taller than Jones.” And yet, all things being equal, Smith has an edge on Jones just because he can change a lightbulb without a stepladder. Even putting such things aside, some people consciously vote on a single issue—abortion, taxes, foreign policy, whatever—but most vote for a bundle of reasons.

To put it very bluntly: You can vote wrong without being a bad person. You can vote right without being a good person. Voting right or wrong does not make you good or bad. Bad people can vote right and good people can vote wrong.

What do I mean by right and wrong, good and bad? Well, that’s the point, isn’t it? Those questions are way upstream of voting behavior. The millions of people who voted for Obama and then voted for Trump didn’t become good or bad because of who they voted for. And the millions of people who voted for Trump and then voted for Biden didn’t change either. Or maybe they did change because their circumstances or interests changed. Or maybe they stayed the same but their estimation of Trump or Biden changed based on how they actually governed. And, for most of them, good and bad don’t even enter the calculation.

Manufacturing an electorate.

What is true for individuals is even more true of the amorphous, inchoate, lava lamp globule we call “the electorate.”

Technically, the electorate is the total share of the population that is eligible to vote. But in political arguments and analysis, we often use the term differently. We use electorate to describe not the people who were eligible to vote, but the people who actually voted. It was routinely said that Barack Obama won in 2008 and 2012 because he “changed the electorate.” Technically he did no such thing; he changed the composition of people who showed up to vote, boosting the share of black and young voters. This is the way I’m using “electorate” here—not the total number of eligible voters, but simply the people who voted.

Every election has a different electorate, and it starts to dissipate the moment the election is over. If the electorate (again the population of people who voted) of 2012 had looked like the electorate of 2004, Romney would have won. This is what political campaigns do: assemble coalitions of voters who temporarily form a majority. The members of those coalitions vote for different reasons based on different priorities and interests—some extremely rational, some quite irrational, and most somewhere in between. All the votes count the same, but you can’t conclude that all of the voters who voted alike voted alike for the same reasons.

Campaigns aren’t the only things that construct coalitions and shape electorates: Government does that too. This is one of the many brilliant points in Yuval Levin’s American Covenant. Yuval writes:

This is an underappreciated fact about every democracy: the structure of the institutions of government creates the contours of the electorate. We tend to think of an election as something like a census of views—an occasion to measure an external reality called public opinion so that we can use the result to determine who should hold political power. We imagine that the public is always divided in a certain way and that elections merely let us see exactly how. But public opinion has to be formed before it can be measured, and it is formed not only on the basis of people’s innate preferences but also in response to the shape of the political system and its work. People don’t just walk around with a strong opinion about who their state’s next governor should be. They form that opinion in response to the question put to them at election time and the choice of answers presented to them. If the question were put differently and the range of options looked different, the same people could well make very different choices. And the questions put to voters are functions of the institutions that need to be populated and of the methods of election that apply to each—or, in other words, they are functions of the structure of the Constitution.

But America isn’t any democracy. Our form of government is distinct. “In most other democracies,” Yuval writes, “winning an election means controlling the agenda for a time. But in the American system, winning an election only grants you the ability to compete for such control with other actors in the system, some of whom have been elected by overlapping but not identical electorates, and all of whom can make their own claims to legitimate authority.”

American presidents aren’t prime ministers who can order everyone in government to do their bidding. A senator is not beholden to the same electorate as a president. Indeed, only a third of senators are on the same ballot as any presidential candidate. But even when they are on the same ballot, and even when they are members of the same party, senatorial candidates get votes the presidential candidate didn’t get, and vice versa. Governors, meanwhile, have an even more distinct electorate, because the issues at play in Kansas are different than those in California. You might vote Republican for senator or president, but Democratic for governor, because on the issues in your home state things like foreign policy matters very little, while local sales taxes or policing matters much more.

One of the many reasons this is important is that when we vote for a presidential candidate, they do not have a mandate to do everything they campaigned on. America doesn’t do mandates. Our system hires people to work with other people we hired to run the government. To the extent mandates exist—I truly don’t think they do—they coexist with equally legitimate mandates going the other way. Republican congressional candidates campaign to stop Democrats, and vice versa all the time. A Democratic president who says to a Republican senator, “I have a mandate to do X” should not be offended when the Republican senator responds, “Yeah, and I have a mandate to stop you from doing X.”

Neither actually has a mandate for anything, other than to do the job as best they can and then be held accountable to voters the next time they run. Mandates are spin, period.

But we talk about mandates as if they’re a political science-y term for the volksgemeinschaft reflecting the soul of the nation the way we talk about votes as a window on the soul of the voters.

It’s all BS.

We hire people to do a job. That’s hard enough when the job candidates are qualified. It gets so much messier when they’re not.

And now, David.

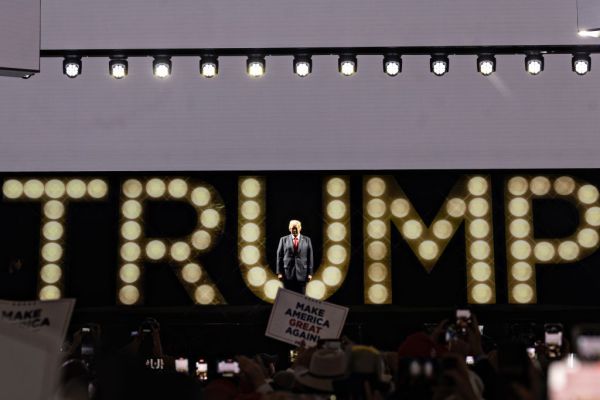

Not surprisingly, I agree with virtually everything David writes about Donald Trump and much else. Including, not surprisingly given the above, this:

I hate the idea that we should condition friendship or respect based on the way in which a person votes. Time and again we make false assumptions about a person’s character based on his or her political positions. There are truly bad actors in American politics, but we cannot write off millions of our fellow citizens who vote their consciences based on their own knowledge and political understanding.

It’s worth noting that everyone who is mad at David for saying he’s going to vote for Kamala Harris isn’t actually mad at him for how he’s going to vote. They’re mad at him for saying he’s going to vote for Harris. That’s a kind of double sacrilege for some people.

For starters, David’s vote matters only marginally less than my own. I live in Washington, D.C., where Biden won 92 percent of the vote. David lives in Tennessee where Trump won, twice, with roughly 61 percent of the vote. So as a matter of demystified, cold, boring, psychological reality, David’s vote is meaningless.

What bothers people is that he’s endorsing Harris over Trump. And this is where I disagree with him. I still love the guy and think he’s one of the most decent and intellectually honest people I know. I just think he’s wrong. Not bad, just wrong.

Indeed, I think he’s doubly, or even triply, wrong: He’s wrong about voting for Harris, he’s wrong for endorsing Harris, and he’s wrong about writing a column pegged to his vote rather than his endorsement.

Let’s start with the vote. To the extent we think of voting as an extension of our values or aspirations or any of that high-minded stuff, if you live in a state where your vote has virtually no chance of making a difference, I think it’s better to send a different kind of signal than the one David is sending. I think sending a message about the kind of candidate you would enthusiastically vote for is preferable to sending a mixed and muddy signal about who you’re voting against.

Democrats and pundits will not read David’s vote as anything other than an endorsement of Harris’ full suite of positions, as stupid as I think that interpretation is. Writing in Mitt Romney, Jack Danforth, Ronald Reagan, Mitch Daniels, Nikki Haley, Ben Sasse, Jack Smith, or even leaving the presidential line blank would send a better—and clearer—message. Why? Because all Harris votes look alike; all non-Trump votes don’t.

Then there’s the endorsement. I don’t really do endorsements, for several reasons. First, because all the fallacies people ascribe to voting are applied even more intensely to endorsements. If Harris issues some heinous executive order, you can be sure David’s inbox will overflow with “this is what you wanted!” nonsense. Second, and more importantly, endorsements trigger an instinctual desire to defend them after the fact. I do not think for a moment that David will feel compelled to defend every bad decision a President Harris would make. But at some level, endorsements make it marginally harder to condemn them. Last, as I’ve written many times, I increasingly think that too many pundits see their role as being players in partisan contests. I don’t have the space to expand much on this, except to say I think it’s complicated. I think institutional endorsements are defensible, but they tend to reinforce the perception that journalistic outlets are part of the partisan industrial complex. Endorsements, both institutional and individual, create a kind of psychological headwind against calling out your side.

Finally, there’s the framing of the endorsement around David’s vote. I think it’s a needless distraction. Dan McLaughlin, another friend I admire, forcefully objected to David’s column. I agree with many of his points, but I think he minimizes the argument that a second Trump presidency would be more damaging to conservatism and the country than a Harris presidency. He reasonably believes that Harris wants to do many un-conservative and bad things. That said, I think conservatism and a chastened GOP would be healthier in opposition to a Harris presidency than in support of a Trump presidency. I certainly could be wrong about that. But, as Dan would surely admit, just because Harris got elected would not mean she could get everything she wanted out of Congress.

I bring up Dan’s objections to illustrate how the discussion of voting needlessly complicates things:

A vote reflects two kinds of choices: a selection between alternatives in who will govern us, and a statement (in the case of a columnist or a leader, a public statement) of what we endorse. There are often tensions between the two, and we all have our own views of how to resolve those tensions and what lines we won’t cross.

I largely agree with that. But again, Dan’s objection is with the endorsement aspect of this—and David’s explanation of it—more than the voting itself. The discussion of voting just muddies the discussion.

After all, Dan agrees with David about Donald Trump. Indeed, Dan also rejected the binary choice in 2016 and 2020. It’s not clear whether he will write in a third choice again this year. (He says he “planned” to do so when the choice was between Trump and Biden, but tantalizingly leaves us hanging about what he’ll do now that the choices are Trump and Harris. I don’t care much about how he votes, but I think he makes the same mistake David did by introducing the topic).

I think Dan’s criticisms fall prey to many of the same problems he ascribes to David. He accuses David of caving, hypocritically or at least without sufficient explanation, to the binary-choice distortion field. I think Dan’s got a point, but his point depends in part on the same thinking. Yes, Harris is terrible going by her record of past positions—and presumably some of her current ones, whatever they may be. Dan isn’t quite suggesting that David now supports Harris’ indefensible positions; he’s miffed that David is unforgivably silent about them. That’s a perfectly fine criticism of a column, but it’s not that powerful a condemnation of a vote. Again, we’re talking about a disagreement between two people who have never voted for Trump.

David’s voting against Trump, and I have no objection to that whatsoever. Dan is certainly voting against Harris, and I have no objection to that either. But beyond that, the argument feels like a contest in whataboutism. They both stink, but in different ways and for different reasons. People want to feel good about their vote because we invest too much in voting as an aspirational expression. But from the vantage point of the conservatism all three of us come from, I think wanting to feel good about your vote is a fantasy.

I think David’s error—hardly fatal in my opinion—was succumbing to both the voter’s desire to feel good about their vote and the columnist’s desire to make a positive case for his position. David’s a remarkably joyful guy, so I have no desire to gainsay his sincere private feelings. But I think trying to do both publicly, as a conservative, is like trying to cross a chasm in two jumps. It’s a bit like his love of Aquaman movies: It’s one thing to express your love, it’s another thing entirely to write out an argument justifying it on rational grounds.

None of this would be necessary if David had simply said, “I think Harris is pretty terrible for a slew of reasons, but a Harris presidency would be the lesser of two evils for the following reasons.” You may disagree with that, and that’s fine. But in my opinion, it would be a better description of reality from a conservative perspective and, I think, a better description of David’s position.

When it comes to national politics, for Reaganite conservatives like Dan, David, and yours truly, it’s all a moveable feast where crap sandwiches are the main dish. No amount of garnish or fancy preparation will change the nature of the meal. And we should have a little grace for those who employ different strategies for how to power through the banquet.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.