Happy Tuesday! An overzealous editor scrubbed this delightful Chicago Bears content from yesterday’s newsletter, but we thought it was important enough to re-include it a day later. [Editor: The Bears win infrequently enough that we decided to let it slide.]

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

Days after the Russian Ministry of Defense announced a “strategic regrouping” of its military forces over the weekend in the face of a Ukrainian counteroffensive near Kharkiv, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov told reporters the invasion of Ukraine “will continue until all the goals that were originally set are achieved,” adding that Russian President Vladimir Putin is in “constant, round-the-clock communication” with his military commanders. The Russian retreat appeared to continue apace on Monday, as U.S. and other Western officials expressed surprise at how effective Ukraine’s push has been.

-

After a March 2022 ceasefire in the conflict was broken last month, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front announced Sunday it is willing to abide by an immediate ceasefire with the Ethiopian government and participate in a peace process under the auspices of the African Union, dropping various demands it had previously set as preconditions for any such talks. The Ethiopian government has yet to respond to the entreaty, but Western governments—including Germany and the United States—encouraged Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed to “seize” the opportunity for peace.

-

Secretary of State Antony Blinken admitted Monday it’s “unlikely” an agreement on a new Iran nuclear deal is reached in the near term, telling reporters Iran’s response to the European Union’s latest proposal tried to “introduce extraneous issues” into negotiations and was “clearly a step backward.”

-

The Justice Department indicated in a filing on Monday it would accept one of the Trump legal team’s proposed candidates—Judge Raymond Dearie—to serve as a special master tasked with reviewing the material retrieved from Mar-a-Lago last month for potentially privileged documents. Dearie, 78, was first appointed to the federal bench by President Ronald Reagan and has served as a district court judge for the Eastern District of New York for nearly 40 years. U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon must now decide whether to approve Dearie for the position, and, more contentiously, outline the scope of the special master’s work.

-

The New York Times reported Monday that, according to “people familiar,” the Justice Department’s January 6 inquiry has ramped up in recent days. Federal investigators have reportedly issued 40 subpoenas related to the investigation over the past week, and seized the phones of two advisers to former President Donald Trump. In addition to requests for information about Trump’s fake electors plan, some of the subpoenas reportedly focus on the activities of Trump’s post-White House “Save America” political action committee.

-

A working paper released Monday by the National Bureau of Economic Research suggests COVID-19 illnesses have reduced the U.S. workforce by about 500,000 people. Researchers from Stanford University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that employees who missed a week of work for COVID-19 were 7 percentage points less likely than employees who didn’t to still be in the labor force a year later, suggesting the long-term health effects of an infection are inhibiting some people’s return to work.

Remember that ‘Cancer Moonshot’?

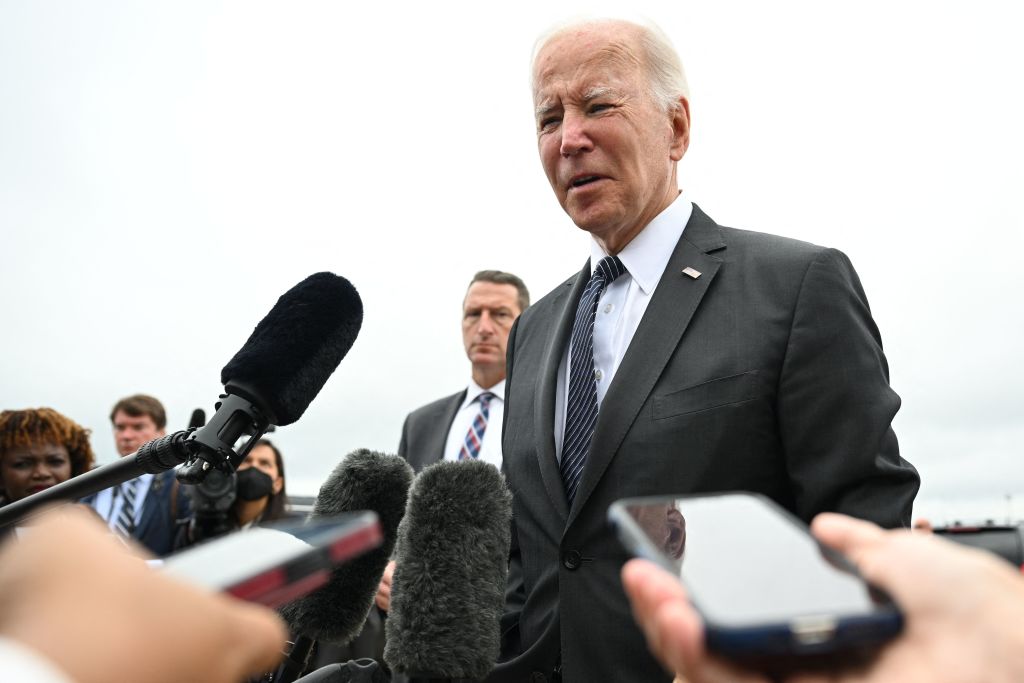

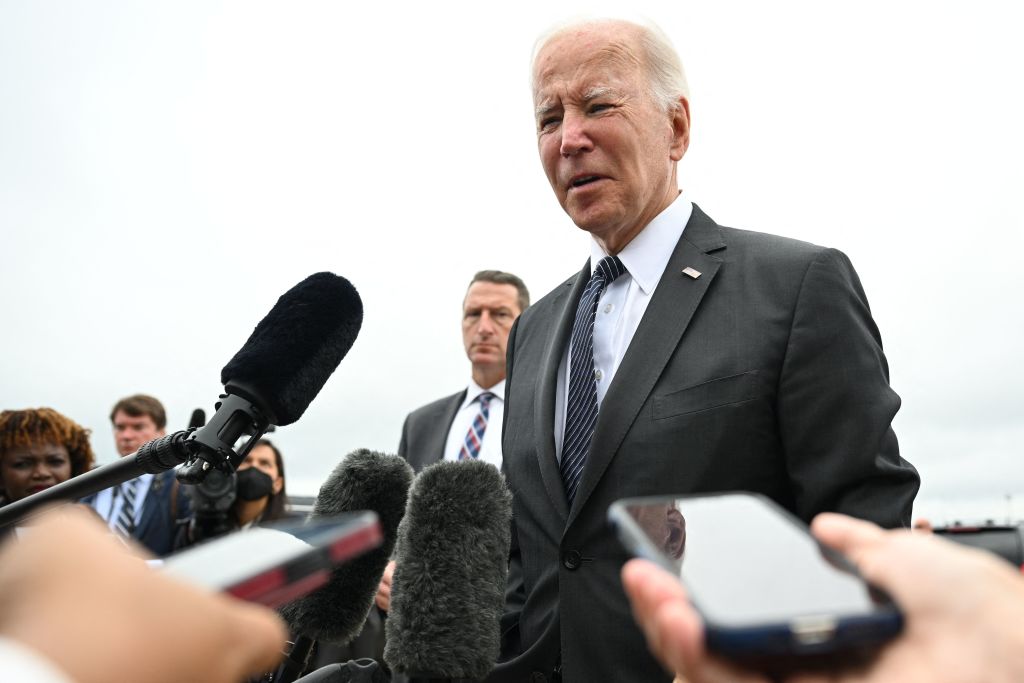

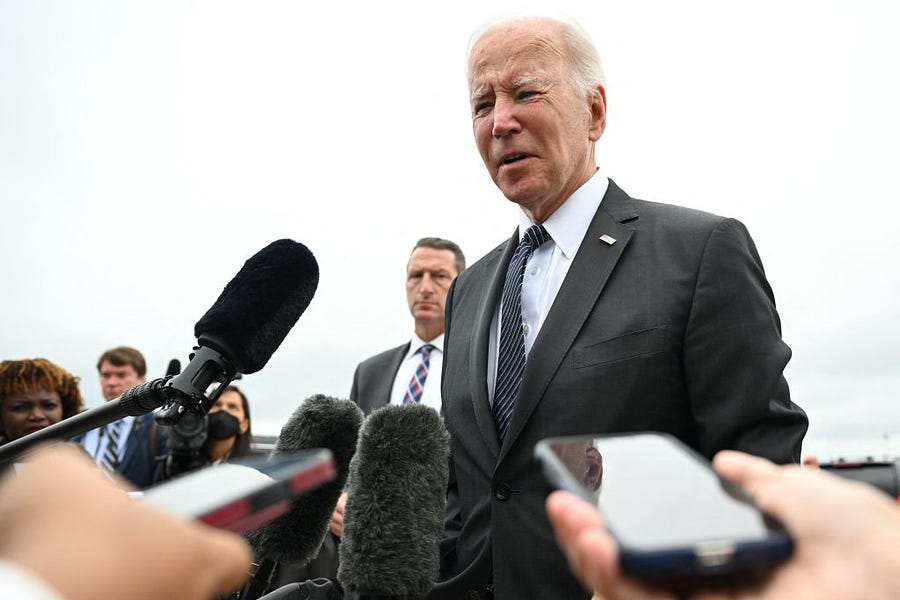

Sixty years ago, President John F. Kennedy took the podium at Rice University and vowed the United States would put a man on the moon before the decade was up. Yesterday, President Joe Biden took the podium at Kennedy’s presidential library in Boston to set a nationwide goal a little closer to home: reducing cancer deaths.

“This cancer moonshot is one of the reasons why I ran for president,” Biden said. “Cancer … doesn’t care if you’re a Republican or a Democrat. Beating cancer is something we can do together.”

He isn’t the first president to take aim at cancer—Richard Nixon declared a “war” on the disease in 1971—but the issue has particular intensity for Biden, whose son Beau died of a brain tumor in 2015. The following year, then-President Barack Obama put Biden in charge of a “Cancer Moonshot” that aimed to accelerate research into cancer vaccines, tumor genetic analysis, and other prevention and treatment methods.

Biden’s formal relaunch of that moonshot effort in February was quickly buried by headlines about the war in Ukraine. But the disease is, of course, an evergreen issue; cancer still trails only heart disease as America’s leading cause of death. The American Cancer Society estimates that 1.9 million Americans will be diagnosed with cancer in 2022. Nearly 610,000 will die of it.

Biden’s carefully phrased speech highlighted the difference between Kennedy’s clear-cut goal and the current president’s more nebulous aim: Biden promised the effort would eradicate cancer “as we know it” and cure cancers, plural—meaning individual types—rather than promising to eliminate cancer as a category of disease. That’s still a tall order, but more realistic as far as research goals go—we’re unlikely anytime soon to have the “cancer is over” equivalent of Neil Armstrong leaving footprints in the moon dust.

Still, Biden is setting his sights high: The revamped cancer initiative aims to reduce age-adjusted cancer deaths by 50 percent over the next quarter century and “improve the experience” of cancer patients and their families.

The cancer effort also doesn’t have freshly built rockets to show off—but the White House on Monday did tout the steps taken so far on research, prevention, and increasing uptake of existing tools. First, the National Cancer Institute has launched a national trial to research blood test cancer screening. If proven effective, blood tests could replace more invasive screenings like colonoscopies, potentially improving screening rates and thus catching more cases early. The study will start with a four-year pilot of 24,000 enrollees.

And the administration wants to boost existing cancer screening uptake, too: Lung cancer still leads cancer deaths in the U.S., but only about 5 percent of eligible patients are being screened. NCI has also set aside $23 million to practice telehealth and study whether it can improve cancer treatment and opened an early-career grant program for cancer researchers.

Meanwhile, the Department of Defense has begun a study to understand how exposure to toxic burn pits during service affects cancer in military members—Congress in August passed a law expanding medical care for exposed veterans. And later that month, the White House released a new policy requiring all federally funded research to be immediately free and accessible upon publication along with its underlying data—a move not limited to cancer work, but which the administration hopes will make it easier for scientists to build upon each other’s research.

On Monday, Biden also announced his choice to head up the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H), established in March with a $1 billion appropriation from Congress. It’s modeled after the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency—a bureaucracy-light Pentagon program dedicated to high-risk, high-reward research and responsible for breakthroughs like Global Positioning Satellite systems and the foundations of the Internet. ARPA-H is intended to fill the gap between the NIH’s focus on basic science and the private sector’s profit-focused attention to immediate practical application. It was bundled under the NIH, which has made some uneasy that it will suffer from that organization’s glacial pace and track record of funding safe-bet research.

Biden’s pick to head the agency, Dr. Renee Wegrzyn, may relieve some of that anxiety—the biomedical scientist formerly worked at DARPA. She’ll also decide how much ARPA-H’s early efforts will focus on cancer—its mandate covers projects “from the molecular to the societal” and research on detecting and treating a range of diseases like Alzheimers and diabetes.

Wegrzyn’s appointment also helps counteract another criticism—that the administration’s science efforts lacked key leaders. Top science adviser Eric Lander resigned days after the February moonshot announcement after admitting he had bullied subordinates, while the job of National Cancer Institute head lingered unfilled for months. The Washington Post cited “cancer advocates and experts” complaining the moonshot effort had been slowed by thin staffing and resources.

The administration also hasn’t asked for a flood of new funding to underwrite ARHPA-H and the cancer initiative, leading some to express concerns they could cannibalize funding from existing agencies like the National Institutes of Health. “There will be no medical breakthroughs or revolutionary discoveries without sustained investments in basic scientific research,” American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology public affairs director Sarina Neote wrote in May. “We urge policymakers to prioritize, not plunder, funding for NIH.”

Evidently undeterred by criticism, Biden leaned on Kennedy’s example to inspire buy-in for the cancer initiative. “President Kennedy set a goal to win the space race against Russia, and advanced science and technology for all of humanity,” Biden said. “I believe we can usher in the same ‘unwillingness to postpone’—the same national purpose that will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills to end cancer as we know it, and even cure cancers once and for all.”

Worth Your Time

-

In the post-Roe era, Ramesh Ponnuru argues, the pro-life movement should remember the approach that got them to to where they are today: incrementalism. “Passionate pro-lifers, in their impatience at what they recognize to be a grave injustice, are forgetting the need for patient persuasion of the public,” he writes for Bloomberg. “Some pro-lifers have made a point of claiming that abortion is never medically necessary. That’s because they don’t consider ending an ectopic pregnancy, for example, as a ‘direct abortion’—an intentional taking of human life. That’s needlessly confusing, and pro-lifers should simply say they’re for an exception in such cases. They should also broaden their agenda to include measures to aid parents of small children—such as the proposals of various Republican senators to expand the child tax credit and to finance paid leave. Promoting a culture of life includes fostering the economic conditions that help it thrive.”

-

Are public opinion researchers making the same mistakes this cycle that led to key polling errors in 2016 and 2020? Possibly. “Wisconsin is a good example,” elections analyst Nate Cohn notes in the New York Times. “On paper, the Republican senator Ron Johnson ought to be favored to win re-election. The FiveThirtyEight fundamentals index, for instance, makes him a two-point favorite. Instead, the polls have exceeded the wildest expectations of Democrats. The state’s gold-standard Marquette Law School survey even showed the Democrat Mandela Barnes leading Mr. Johnson by seven percentage points. But in this case, good for Wisconsin Democrats might be too good to be true. The state was ground zero for survey error in 2020, when pre-election polls proved to be too good to be true for Mr. Biden. In the end, the polls overestimated Mr. Biden by about eight percentage points. Eerily enough, Mr. Barnes is faring better than expected by a similar margin. The Wisconsin data is just one example of a broader pattern across the battlegrounds: The more the polls overestimated Mr. Biden last time, the better Democrats seem to be doing relative to expectations. And conversely, Democrats are posting less impressive numbers in some of the states where the polls were fairly accurate two years ago, like Georgia.”

-

Publicly, Joe Biden and Barack Obama are the best of friends. But their relationship is far more complicated than first meets the eye, Gabriel Debenedetti reports in his forthcoming book, from which Politico published an excerpt on Monday. “Obama had thought his old VP seemed tired ever since they’d first caught up after leaving office, and the prospect of him going through a draining campaign seemed unthinkably painful,” Debenedetti writes. “His concern was reputational, too. Obama figured that if Biden’s campaign failed, the former VP’s legacy and ultimately his memory would be painted by that embarrassment—as would Obama’s. Wouldn’t he want to go out on top, with the public’s final memory of him more ‘Medal of Freedom’ than ‘1 percent in Iowa’? The problem, as Obama saw it, was that he couldn’t say anything like this to Biden himself. … He was left sitting in his office quietly, wondering if maybe some other candidate would catch enough fire before Biden even launched to dissuade him from trying. So when they finally started talking about it outright, Obama’s message was crafted to be caring, not calculating, even if his hope to convince Biden was obvious to the ex-VP.”

Presented Without Comment

Also Presented Without Comment

Also Also Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

-

It’s Tuesday, which means Dispatch Live is back! Tune in at 8 p.m. ET/5 p.m. PT for a conversation between Jonah, Klon, and Adam about the latest developments in the Russia-Ukraine war. Is the Ukrainian counteroffensive the real deal? How will Russia respond? If you have any questions you want them to address, be sure to drop them in the comments here!

-

On the site today, Andrew has a report from Georgia about Republican candidate Herschel Walker’s Senate campaign reset after a gaffe-filled summer, which seems to be giving him a polling boost in his contest against Sen. Raphael Warnock.

Let Us Know

Succession, Ted Lasso, The White Lotus, and Squid Game cleaned up at the Emmy Awards last night. Do you watch any of the shows that were nominated? And can you believe that Rhea Seehorn was snubbed again for her portrayal of Kim Wexler on Better Call Saul?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.