Happy Thursday! It’s National Banana Day. Happy National Banana Day to all who celebrate.

(Fun fact: One of your Morning Dispatchers has eaten the same exact thing for breakfast—two-ingredient banana pancakes—every day for the better part of four years.)

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

President Joe Biden formally announced on Wednesday his administration’s plans to remove all U.S. troops from Afghanistan by September 11, 2021.

-

Members of the Centers for Disease Control’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices opted not to vote yesterday on the future of Johnson & Johnson’s COVID-19 vaccine, arguing more data are needed to determine the extent of a rare blood clotting side effect.

-

In a reversal of a Trump-era policy, the Biden administration’s Department of Health and Human Services on Wednesday proposed new rules that would permit abortion clinics to access federal family-planning funds for contraception and other health services for low-income Americans.

-

GOP Rep. Kevin Brady of Texas—the former House Ways & Means Committee chairman who led the push for Trump’s 2017 tax cuts—announced Wednesday he will not seek a 14th term in 2022.

-

Although preliminary CDC data from a few weeks ago showed a 5.6 percent decline in suicides over the past year, additional preliminary data released yesterday showed a stark increase in deaths attributed to drug overdoses: 87,000 in the 12 months leading up to October 2020, a nearly 29 percent increase over the same time period a year earlier.

-

The Department of Justice on Wednesday closed its investigation into the death of Ashli Babbitt, the Trump supporter killed by a U.S. Capitol Police officer in the Capitol on January 6, and announced it will not be pursuing criminal charges against the officer.

-

Kim Potter, the former Brooklyn Center police officer who fatally shot Daunte Wright last weekend, was charged with second-degree manslaughter on Wednesday, and released on bond.

-

Bernie Madoff, the mastermind behind one of the largest ponzi schemes in Wall Street history, died Wednesday at age 82, a decade into his 150-year prison sentence.

-

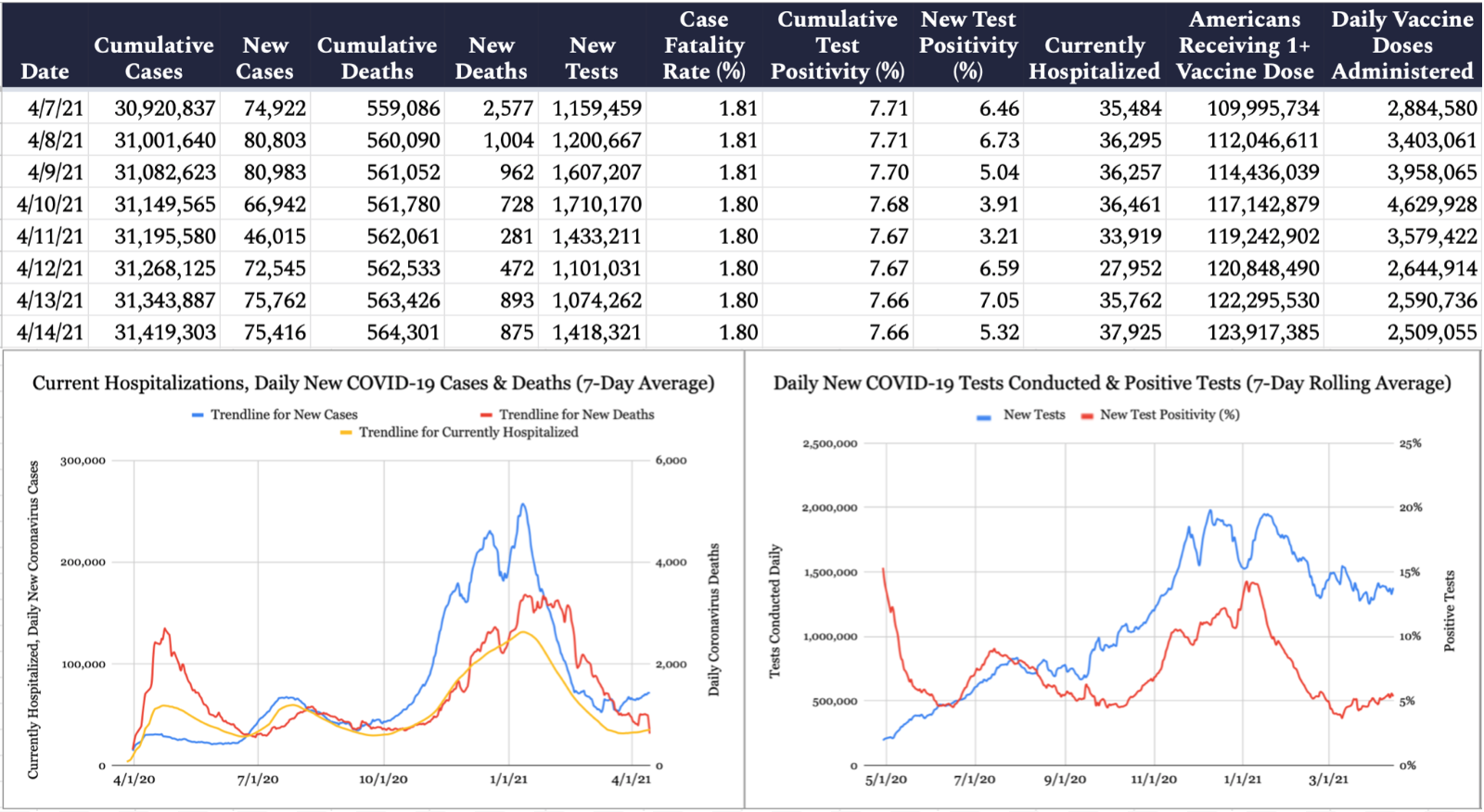

The United States confirmed 75,416 new cases of COVID-19 yesterday per the Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard, with 5.3 percent of the 1,418,321 tests reported coming back positive. An additional 875 deaths were attributed to the virus on Wednesday, bringing the pandemic’s American death toll to 564,301. According to the Centers for Disease Control, 37,925 Americans are currently hospitalized with COVID-19. Meanwhile, 2,509,055 COVID-19 vaccine doses were administered yesterday, with 123,917,385 Americans having now received at least one dose.

The End of the Afghanistan War

President Biden made it official yesterday: The United States’ longest war will soon be coming to an end.

“We cannot continue the cycle of extending or expanding our military presence in Afghanistan, hoping to create ideal conditions for the withdrawal, and expecting a different result,” Biden said, announcing the Pentagon will begin withdrawing the 3,500 or so U.S. troops remaining in the region on May 1. “I’m now the fourth United States President to preside over American troop presence in Afghanistan: two Republicans, two Democrats. I will not pass this responsibility on to a fifth.” He noted that he called former President Bush earlier this week to inform him of his decision.

Bringing the troops home from the conflict—launched in October 2001, costing more than 2,400 American lives and $2 trillion—was, at least rhetorically, a priority of both the 44th and 45th presidents. In May 2012, Obama pledged that the “Afghans will be fully responsible for the security of their country” by the end of 2014—a promise Biden himself reiterated in the vice presidential debate that fall. Trump ran on ending the United States’ “forever wars” in 2016, and his Secretary of State Mike Pompeo negotiated a deal with the Taliban and Afghan government in February 2020 that would have withdrawn U.S. forces by May 1 of this year had Trump been reelected.

In each instance, top military officials have pushed back, arguing Afghanistan’s government was not yet ready to stand on its own. Retired Army Gen. Jack Keane summarized the arguments well when he was asked yesterday what he predicts will happen once American forces are gone later this year. “That government is going to be undermined and so will the [Afghan National Security Forces],” he told Fox News. “A civil war will break out and [there is] a very real possibility of the Taliban taking over. … And certainly it is fertile opportunity for Al Qaeda to re-establish their safe haven once again.”

A senior administration official told reporters Tuesday that the withdrawal plan is not conditions-based, because Biden determined that a conditions-based approach “is a recipe for staying in Afghanistan forever.”

“I believed that our presence in Afghanistan should be focused on the reason we went in the first place: to ensure Afghanistan would not be used as a base from which to attack our homeland again. We did that, we accomplished that objective,” Biden said yesterday. “Our reasons for remaining in Afghanistan are becoming increasingly unclear.”

“When will it be the right moment to leave? One more year, two more years, ten more years?” he continued. “‘Not now’—that’s how we got here.”

Thomas Joscelyn—senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and The Dispatch’s resident Middle East expert—understands Biden’s reasoning, even if he doesn’t ultimately agree with the decision to withdraw. “You’re basically going to end up at the same decision point every three, six, 10 months,” he said, noting the Taliban has done “absolutely nothing” to live up their counter-terrorism assurances in the agreement with the Trump administration. “There’s never going to be a clear point to leave, really. I think [Biden] has a point there on that. If you want to get out, and you don’t want Americans there forevermore, then that kind of makes sense.”

“I think basically they used the Trump administration agreement with the Taliban as an offramp for what he wanted to do,” he continued. “If you stay, you say, ‘I’m not going to get out this year, or within a few months of that deadline, I’m not going to pull the plug,’ then you are there indefinitely.”

Still, the move comes with real downside risk, and the no-strings-attached withdrawal—symbolically by September 11, no less—is already being spun by the Taliban and al-Qaeda as an unequivocal win.

Republican national security hawks were predictably apoplectic. Sen. Lindsey Graham called Biden’s move “dumber than dirt,” adding that he essentially “canceled an insurance policy against another 9/11.” Rep. Liz Cheney argued it “will provide an opportunity for terrorists to be able to establish safe havens again.”

“While many fatigued Americans characterize U.S. engagement in Afghanistan as a ‘forever war,’ the reality is that America’s presence in Afghanistan is no longer the same combat mission that began after the September 11, 2001 terror attacks,” Rep. Adam Kinzinger—who himself has served in Afghanistan and Iraq—wrote. “It has evolved into a mutually beneficial partnership, where each side serves as an insurance policy on security for each other.”

It wasn’t just Republicans ringing alarm bells. Democratic Sen. Jeanne Shaheen of New Hampshire expressed her disappointment, saying “the U.S. has sacrificed too much to bring stability to Afghanistan to leave without verifiable assurances of a secure future.” Washington Post columnist David Ignatius described it as a “gutsy move” because “the price of being wrong is enormous.”

“Sometimes cutting the knot and removing U.S. troops opens the way for peace; more often, in recent years, it has been a prelude to greater bloodshed,” he wrote. “The downside is easy to imagine: a spiral of violence in which provincial capitals fall, one by one, leading to a deadly battle for Kabul—a fight in which the people who believed most in the United States’ intervention will be at greatest risk, and pleading for help. Closing our eyes and ears to that catastrophic situation—turning away from the desperate appeals, especially from the women of Afghanistan, who fear new oppression—will require cold hearts and strong stomachs.”

Afghan President Ashraf Ghani tweeted yesterday that Afghanistan “respects the U.S. decision and we will work with our U.S. partners to ensure a smooth transition.”

“Afghanistan’s proud security and defense forces are fully capable of defending its people and country, which they have been doing all along, and for which the Afghan nation will forever remain grateful,” he said.

Joscelyn is more skeptical. “The question is not ‘are parts of Afghanistan going to fall’ or ‘is the entirety of Afghanistan going to fall,’” he said. “It’s really ‘how quickly are parts of Afghanistan going to fall,’ because parts of it are going to fall pretty fast.”

For more on this topic, keep your eyes out for Joscelyn’s Vital Interests newsletter later this afternoon.

Johnson & Johnson Still in Limbo

When the FDA and CDC released emergency guidance on Tuesday recommending an immediate pause in Johnson & Johnson’s COVID vaccine due to concerns about extremely rare blood clots—which we covered at length in yesterday’s TMD—they said the pause would go into effect until the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) had had a chance to analyze and assess the newly discovered risks. ACIP met for hours yesterday afternoon, but ultimately decided to delay a vote on how to respond to the news, citing a need to accumulate more evidence over the next week or two.

“To be very frank, I do not want to vote on this issue today,” said committee member Dr. Beth Bell, the former director of the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, during the call, which was streamed online. “I do not want to vote not to recommend the vaccine; I think that is not really something I necessarily believe. But I do not feel that we have—it’s not surprising, we’ve been looking at this issue for two days or less—I just don’t feel that we have enough information to make an evidence-based decision.”

What information does the ACIP think is lacking? Not the actual connection between the vaccine and the rare side effect—as we discussed yesterday, that seems well substantiated. But the committee members argued that more cases than the six known ones might be lurking undiscovered in already collected vaccine safety data—cases in older people, for instance, that might initially have been misidentified as stroke. A continued pause would give them time to discern, in the words of one conference attendee, whether this was “a needle in the haystack or the tip of an iceberg.”

Throughout the meeting, scientists continued to stress that the pause was being taken out of an abundance of caution—or as a luxury, even, given that the United States has widespread access to two other extremely effective vaccines not implicated by serious possible side effects, no matter how rare.

“We are very fortunate because we have multiple other alternatives in the U.S. to help stop this pandemic,” said committee member Dr. Helen Keipp Talbot, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt. “I think that puts us in a little bit of a different position, and we can be much more cautious and thoughtful and use the old motto of ‘first do no harm.’”

Some non-ACIP physicians participating in the call were less enthusiastic about prolonging the pause, however. “I must express concern about the direction that I fear the committee may be going,” said Dr. Nirav Shah, an epidemiologist who serves as the director of Maine’s CDC. “We are in a situation where not making a decision is tantamount to making a decision. And the extension of the pause will invariably result in the fact that the most vulnerable individuals in the United States, who were prime candidates for the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, will remain vulnerable.”

Dr. Amanda Cohn, ACIP’s executive secretary, offered assurances that the committee took such concerns seriously and was committed to a quick resolution. “I completely agree that we definitely don’t want it to feel like an indefinite pause. … If there is no motion or desire to vote on a recommendation today, that would result in us going back to work as quickly as possible and coming back with an additional emergency meeting in a week, 10 days, two weeks at most.”

Unemployment Boost Taking a Toll

It’s wild to think it’s been more than a year since we first wrote to you about the expanded federal unemployment insurance implemented by the CARES Act. At the time, a handful of Republicans were concerned about the impact the provision would have on the labor market.

“Unless this bill is fixed, there is a strong incentive for employees to be laid off instead of going to work,” GOP Sens. Tim Scott, Ben Sasse, and Lindsey Graham wrote at the time. “This isn’t an abstract, philosophical point—it’s an immediate, real-world problem.”

Early in the pandemic, the approach may have made some sense. Not only were tens of millions of people suddenly out of work through no fault of their own, we also wanted people to stay home to slow the spread of the virus—so the federal government effectively paid people to do just that. But with vaccinations on the rise and restrictions being lifted across the country, the weekly boost—since reduced from $600 to $300—has the potential to dramatically hinder our economic recovery.

In a piece for the site today, Steve talked to a dozen small business owners across the country—as well as a few economists—about the impact of the law on the labor market.

How is this manifesting in communities around the country?

“I’ve been in business for 33 years—10 years here, 33 years in Maumee—this is the absolute worst it’s ever been,” says Bill Anderson, co-owner of Dale’s Diner in Waterville, Ohio, which is going out of business. It’s primarily back-of-the-house employees he needs—dishwashers, managers, cooks. “Usually, we’ll put ads in in different locations to get people and we’ll get anywhere from six to 12 applications in the first week or whatever and we’ll get to take our pick—we’ll get to pick the best of that bunch. …Within the last couple of months, we don’t even get a call—we don’t get anything.”

The Andersons—and the dozen small and medium business owners we spoke to for this report—say generous unemployment is the primary problem. A line cook at Dale’s Diner starts at $11 per hour, up $2 per hour over what it was before the pandemic, according to Bill Anderson. That’s $440 per week or $1,760 per month—roughly $21,000 per year, not including overtime and bonuses.

But pandemic-driven unemployment often pays more—sometimes far more. In Ohio, according to data from the Ohio Department of Jobs and Family Services, the state provided weekly unemployment benefits that averaged nearly $340. Add to that the unemployment supplements from the federal government—which have ranged between $300 and $600 per week, depending on which COVID relief law funded them—and you have some workers paid between $640 and $940 per week to stay home, between $33,000 and almost $50,000 on an annualized basis.

The Andersons have had to ask more of their current staff. More hours, more flexibility, more patience. But they lived in such fear of an employee quitting that they were reluctant to ask them even to do routine jobs. “You tiptoe around,” says Liz. “You say: ‘Can you clean this … please?’ You’re very cautious.” They preemptively offered financial rewards to some of their key employees, including a $1,500 loyalty bonus to their kitchen manager. It didn’t work. “The last straw,” says Liz, “our kitchen manager just walked. When she walked, I said—‘We just can’t do this anymore.’ Our life was really being negatively affected by this.”

Worth Your Time

-

Last February, the New York Times compiled a series of photographs from the war in Afghanistan, America’s longest. Given yesterday’s news, it’s worth taking another look and reflecting on the two-decade long history of the conflict in the region. And also in the Times, Afghanistan war veteran Timothy Kudo reflects on his experience now that American involvement in the conflict is coming to an end. “For a long time, my faith that the war might be won quieted moments of doubt,” he writes. “What of the Afghan people, who will remain at war long after we leave?”

-

In a piece for The Atlantic, Manhattan Institute President Reihan Salam focuses on the campaign donation matching provision in Democrats’ H.R. 1 bill, which he argues is “likely to boost ideologically extreme candidates who devote their time and energy to cultivating a national donor base.” Instead, he writes, Congress should abandon this proposal outright or limit the matching to funds from in-district donors only. Also: Instead of focusing on independent redistricting commissions, Salam argues in favor of expanding the size of the House.

Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

-

In Wednesday’s G-File (🔒) Jonah explains why the New Right—the nationalist populist folks—are starting to look a lot like the Old Left. “With the exception of Pat Buchanan, in my lifetime, virtually no prominent conservative championed anything like industrial policy, corporatism, or ‘economic planning,’” he writes. But Hillbilly Elegy author J.D. Vance, for example, has argued that the government ought to slap more taxes on corporate giants for bowing to progressive demands on voting rights activism, but cut taxes on companies that pay their workers “good wages.” Per Jonah, ideas like Vance’s are nothing more than “old liberal thinking gussied up as bold new conservatism.”

-

Some folks on the New Right are critiquing foreign direct investment (FDI) in the U.S. economy, so Scott Lincicome decided to dedicate an entire Capitolism newsletter (🔒) to the subject. FDI “produces real economic benefits above and beyond those that would have been generated in its absence—regardless of whether it entails breaking ground on a new facility or acquiring one that already exists, and totally leaving aside what U.S. sellers do with the foreign capital they’ve just received,” he writes.

-

Will the FDA’s decision to pause the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine this week fuel vaccine hesitancy? Sarah, David, Jonah, and Chris Stirewalt discuss on the latest episode of the Dispatch Podcast. Plus: Ross Douthat’s latest piece on what Bidenism owes to Trumpism, the GOP’s push for First Amendment retribution against woke corporations, and what Democratic pollsters have learned from their poor electoral forecasting leading up to the 2020 election.

Let Us Know

Is it time to bring our last few thousand troops home from Afghanistan? Or is retaining a small force in the country in perpetuity worth the security benefits?

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Haley Byrd Wilt (@byrdinator), Audrey Fahlberg (@FahlOutBerg), Charlotte Lawson (@charlotteUVA), Ryan Brown (@RyanP_Brown), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.