Happy Tuesday! The Major League Baseball season is officially set to start on time (pitchers and catchers report to spring training in about two weeks!), so it’s a Happy Tuesday indeed.

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

The Defense Department on Monday announced a $230 million deal with Ellume, an Australian company whose at-home rapid COVID-19 test the Food and Drug Administration granted an emergency use authorization in December. Ellume will initially provide 8.5 million tests to the federal government, and be able to manufacture 19 million per month once U.S. manufacturing is at full capacity.

-

President Biden on Monday night reimposed a 10 percent tariff on aluminum imports from the United Arab Emirates that President Trump rescinded just days before he left office last month. “In my view,” Biden wrote, “the available evidence indicates that imports from the UAE may still displace domestic production, and thereby threaten to impair our national security.”

-

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell waded into the intra-GOP squabbles last night, declaring Rep. Liz Cheney “an important leader in our party and in our nation” and decrying Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene’s embrace of “loony lies and conspiracy theories” as a “cancer for the Republican Party.”

-

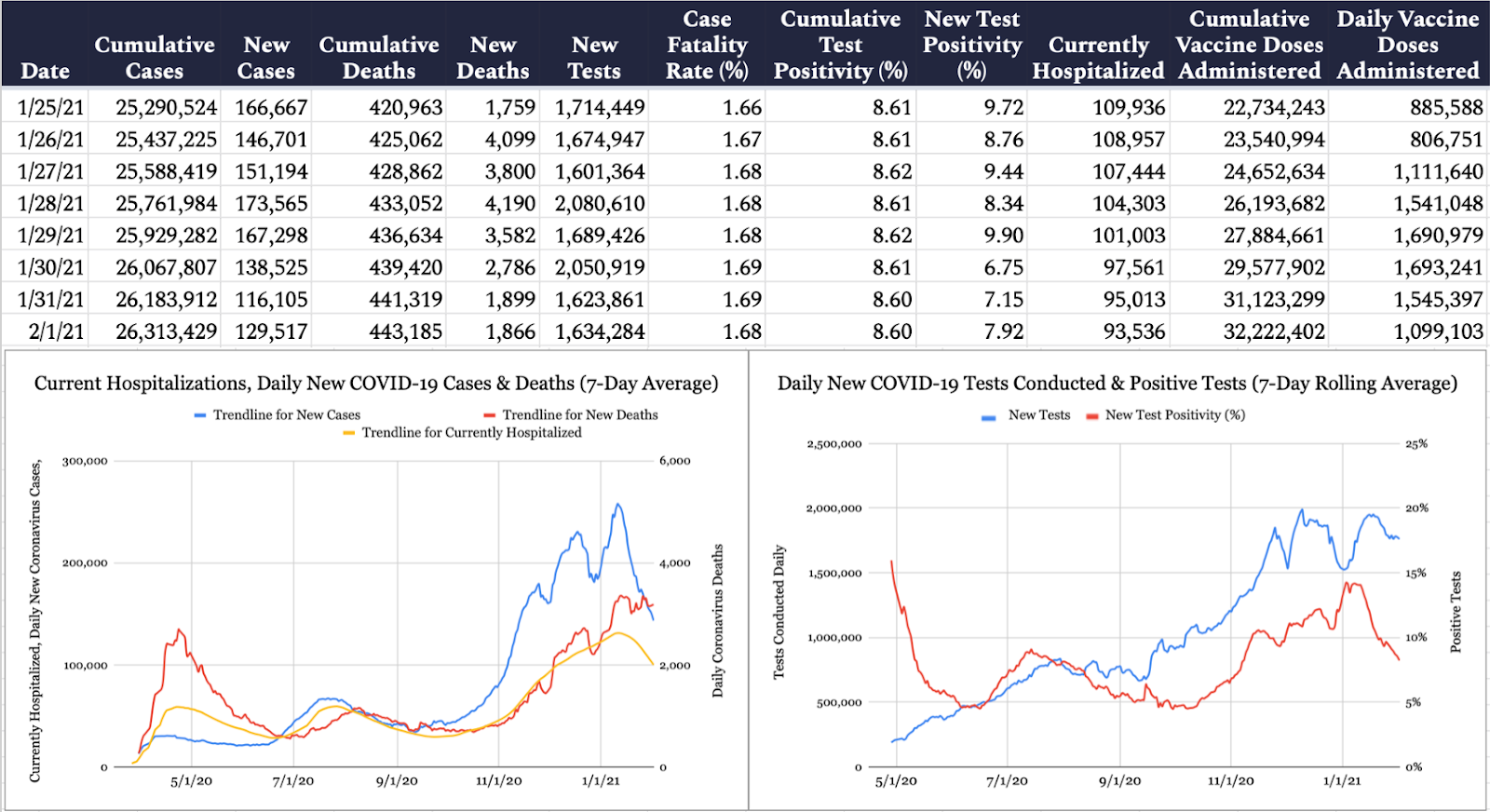

The United States confirmed 129,517 new cases of COVID-19 yesterday per the Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard, with 7.9 percent of the 1,634,284 tests reported coming back positive. An additional 1,866 deaths were attributed to the virus on Monday, bringing the pandemic’s American death toll to 443,185. According to the COVID Tracking Project, 93,536 Americans are currently hospitalized with COVID-19. According to the Centers for Disease Control, 1,099,103 COVID-19 vaccine doses were administered yesterday, bringing the nationwide total to 32,222,402.

Biden Faces His First Legislative Test: Bipartisanship, or Go It Alone?

Your Morning Dispatchers were all set to tackle the bipartisan coronavirus relief package meeting at the White House yesterday when Haley let us know she was already on it for her Uphill newsletter (which you should subscribe to if you haven’t already):

A group of 10 Republican senators met with President Joe Biden last night to pitch their coronavirus relief proposal. The senators are calling for a $618 billion aid package in response to Biden’s nearly $2 trillion plan.

“It was a very good exchange of views,” Maine Sen. Susan Collins told reporters afterward. “I wouldn’t say we came together on a package tonight. No one expected that in a two-hour meeting, but what we agreed to do is to follow up and talk further at the staff level and amongst ourselves and with the president and vice president on how we can continue to work together on this very important issue.”

The GOP framework allocates billions for vaccine distribution, testing expansion, and schools. It would send a round of $1,000 checks to Americans under certain income thresholds. The checks would phase out earlier than Biden’s plan, capped at an income of $50,000 for singles and $100,000 for joint filers. Families would receive an additional $500 per dependent, including both children and adult dependents.

The Republican plan would also extend the $300 per week federal unemployment benefits, currently set to expire in March, until July. Biden has called to expand the unemployment benefits to $400 per week and extend them through September.

The GOP proposal is miles apart from Biden’s. The president has expressed a willingness to work on a bipartisan basis, but top administration officials say they want to pass something big. Democrats in Congress want to move swiftly on Biden’s plan and intend to kickstart a special budget process this week that requires fewer votes to pass legislation in the Senate than is typically necessary. That process, known as reconciliation, will enable them to pass the aid package under a simple majority in the Senate, without support from Republicans.

You can read more about reconciliation in last Friday’s Uphill. It’s the kind of thing congressional leaders do if they are preparing to move ahead on a partisan basis. Republicans used reconciliation for their failed effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act. They also used it to advance their 2017 tax bill.

“While there were areas of agreement, the president also reiterated his view that Congress must respond boldly and urgently, and noted many areas which the Republican senators’ proposal does not address,” said White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki.

She added that Biden reiterated during the discussion “that he will not slow down work on this urgent crisis response, and will not settle for a package that fails to meet the moment.”

Democrats are not going to accept a deal from Republicans roughly a third of the size of Biden’s proposal. They want to pass a sweeping package with many of their priorities, including money for state and local governments and a $15 per hour federal minimum wage.

“I think the Republican offer is sincere, but Biden and Republicans have VERY different ideas for how we address this crisis and voters very deliberately chose Biden’s agenda,” said Sen. Chris Murphy, a Connecticut Democrat. “Some compromise is always warranted, but we have an obligation to see the voters’ intent through.”

For more details about the discussion—and additional machinations of House Democrats and Republicans—check out the full issue of Uphill.

Myanmar’s Military Coup

In the early hours of Monday morning, the Burmese military carried out a coup to overthrow Myanmar’s fragile but promising new civilian government headed by 75-year-old Aung San Suu Kyi. In a series of home raids, the armed forces arrested Suu Kyi, President Win Myint, and other democratically-elected leaders belonging to the majority National League for Democracy (NLD) party.

For the Burmese, the military takeover was like a bad case of déjà vu: From 1962 to 2011, the country existed under the control of the armed forces. During the final 22 years of that occupation, the military junta ruled with an iron fist. Suu Kyi—who was put under house arrest between 1989 and 2010 for her political activism—led the charge to introduce democratic reforms before becoming the de facto leader of the Southeast Asian country in 2016.

The military’s intentions first became clear when the army-owned Myawaddy TV station announced Monday that power had been passed to the country’s commander-in-chef, Min Aung Hlaing, ostensibly for one year. Myanmar was set to begin a new session of parliament following an election in which the NLD won 396 of 476 available parliamentary seats. But the military-backed party alleged voter fraud—without evidence, according to the country’s election commission—and the country was set on the path to what eventually occurred this week.

Taking the power out of the hands of the people and into its own, the armed forces declared that several key positions within the government had been replaced by approved personnel. As of yesterday, 24 ministers and deputies were stripped of their titles. Vice President Myint Swe—a former general with ties to Than Shwe, the notorious junta leader—took over as acting president.

In a letter shared to her Facebook page, Suu Kyi denounced the coup as illegitimate and encouraged her supporters to resist. “I urge people not to accept this, to respond and wholeheartedly to protest against the coup by the military,” she wrote.

But despite a series of reforms spearheaded by Suu Kyi, the military never fully lost its grip over the country. A clause in the 2008 constitution lays out a legal mechanism by which the military can seize power in the event of an emergency—in this case, “voter fraud”—ultimately undermining the authority of a civilian government.

“In 2015, Burma’s democratic elections brought Aung San Suu Kyi’s pro-democracy party to office—but not truly to power,” GOP Leader Mitch McConnell said in a statement Monday. “The military has continued to maintain its corrupt, corrosive hold on the economy, thwart constitutional and political reform, and perpetuate terrible conflicts with ethnic minorities that remain an obstacle to peace and democracy.”

President Biden condemned the military coup yesterday, making clear that his administration would reevaluate its sanction policy toward Myanmar. “The international community should come together in one voice to press the Burmese military to immediately relinquish the power they have seized, release the activists and officials they have detained, lift all telecommunications restrictions, and refrain from violence against civilians,” Biden said. “The United States removed sanctions on Burma over the past decade based on progress toward democracy. The reversal of that progress will necessitate an immediate review of our sanction laws and authorities, followed by appropriate action.”

“At a time when Asia—particularly Southeast Asia—has been seeing a general democratic backslide, Myanmar’s fragile democratic transition was giving a lot of people hope,” Gregory B. Poling, a senior fellow for Southeast Asia and director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at CSIS, told The Dispatch.

“From a policy perspective, Myanmar sits at the core of a lot of intersections of U.S. policy in the Indo-Pacific,” Poling added. Geographically, Myanmar is wedged between India and China, a region that has seen quite a bit of territorial conflict in recent years.

The coup “is likely to be a long term problem for U.S. policy, not just in Myanmar but throughout the Indo-Pacific,” he said. “This touches on everything the administration is going to want to do in Asia, because Myanmar occupies such a symbolically and literally important place in all these regional institutions.” The country is a party to the ten-member Association of South-East Asian Nations.

“The attack on our own democracy on January 6th creates an even greater challenge for us to be carrying the banner of democracy and freedom and human rights around the world because, for sure, people in other countries are saying to us, ‘Well, why don’t you look at yourselves first?’” Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in an interview yesterday. “The difference, though, between us and so many other countries is that when we are challenged, including when we challenge ourselves, we’re doing it in full daylight, with full transparency. We’re grappling with our problems in front of the entire world.”

Worth Your Time

-

As COVID-19 clinical trial data trickle out, we’ve been bombarded by various statistics regarding the efficacy of vaccines: Pfizer is 95 percent effective, Johnson & Johnson is 72 percent effective, and so on. But is that the right way to be thinking about their usefulness? “All five vaccines with public results have eliminated COVID-19 deaths,” David Leonhardt of the New York Times wrote in his newsletter yesterday. “In the official language of research science, a vaccine is typically considered effective only if it prevents people from coming down with any degree of illness. With a disease that’s always or usually horrible, like ebola or rabies, that definition is also the most meaningful one. But it’s not the most meaningful definition for most coronavirus infections.”

-

In the months and years to come, the Biden administration will be faced with the task of how to deal with the mess left by President Trump’s trade war against China. By all accounts, Dion Rabouin writes in Axios, the war was a failure. “The trade war was billed as a plan to bring China to its knees by choking off the all-important American market with 25% tariffs on many imports that would rein in the U.S. trade deficit, boost American exports and slow China’s rise as a global superpower,” he notes. Instead, the conflict failed to reduce the U.S. trade deficit while costing the U.S. a king’s ransom in lost economic growth and hundreds of thousands of jobs.

-

Over the past year, a huge chunk of the country has gotten used to remote work in some form. And the phenomenon might stick around, even as the pandemic recedes. “The impediment to widespread remote work in 2019 and before wasn’t technological. It was social,” Derek Thompson writes in a piece for The Atlantic. “The most important outcome of the pandemic wasn’t that it taught you how to use Zoom, but rather that it forced everybody else to use Zoom,” economist David Autor told Thompson. “‘We all leapfrogged over the coordination problem at the exact same time.”

Presented Without Comment

Also Presented Without Comment

Also Also Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

-

On Monday’s episode of Advisory Opinions, Sarah and David break down the intra-party kerfuffles roiling both the Democrats and the GOP. Did Vice President Harris’ encroaching on Sen. Manchin’s turf do lasting damage to the Biden administration’s ability to work with the Senate? Then, the pair put their lawyer skills to the test making what they see as the best possible defense of President Trump in the impeachment trial set to kick off this month.

Let Us Know

Today’s Morning Dispatch provides an example of how American journalists cover democratic backsliding in a foreign country. What would it look like if we used the same reporting style to describe the events that took place here from November to January?

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Haley Byrd Wilt (@byrdinator), Audrey Fahlberg (@FahlOutBerg), Charlotte Lawson (@charlotteUVA), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.