Appetizer

Today is a BIG day in our politics. History making. And not necessarily in a good way. Nope, I’m not talking about that. In fact, I decided that if you wanted to read about that, you have plenty of other options. If you want my thoughts on that, you can read them here. But this newsletter ain’t doing it.

So where were we? Oh yes! The Wisconsin Supreme Court election that is being held today. By last count, the race has sucked in more than $45 million, which isn’t just more than any other Supreme Court race in our country’s history—it’s three times more. The ads are ubiquitous as they are vicious. And the two candidates in this “nonpartisan” primary—liberal Janet Protasiewicz and conservative Daniel Kelly—aren’t covering themselves in judicial glory.

Any potential judge isn’t supposed to prejudge the outcome of any case that could appear before them, but as Reid Epstein at the New York Times reported back in February:

Judge Protasiewicz has pioneered what may be a new style of judicial campaigning. She has openly proclaimed her views on abortion rights (she’s for them) and the state’s legislative maps (she’s against them).

Ditto the other guy.

Justice Kelly said only legislators could overturn the state’s 1849 abortion ban, enacted decades before women were allowed to vote. He said that complaints about the maps amounted to a “political problem” and that they were legally sound.

And I don’t like it.

Last week, I talked about why I actually do like electing prosecutors and district attorneys. Political accountability is kind of what this whole experiment in self government is about. And in the vast majority of cases, political accountability with all its drawbacks is better than the drawbacks of the alternative. But there are exceptions.

In our federal system, the Department of Justice is shielded from direct political accountability, but the attorney general reports to the president, who is as accountable as they come. But that’s not true for Article III. The Founders intentionally shielded federal judges from all political accountability. They’ve got life tenure and you can’t touch their salaries. The only way to remove a federal judge is to convict them in an impeachment trial.

As a result, we’ve got some mediocre federal judges out there. A few bad ones, too. I’ll also note that the process of getting confirmed as a federal judge has become much more partisan in the last 40 years. I think it’s gotten even more partisan in the last 10 years since Democrats ended the judicial filibuster for lower court nominees and Republicans ended it for Supreme Court nominees. I’m not a fan of any of it. But even so, it ain’t nothing compared to this nonsense.

Outcomes matter in legislative and executive races. Did my legislator vote for the law I wanted? Did the executive enforce the law in a way that addressed the problem we were trying to solve? Did crime go down on his watch? Did taxes go up? All of those are fine issues for campaigns and rely on political accountability.

But now let’s do it with a judge. Let’s say the judge has a case where Bob has been convicted of sexually assaulting a minor. To ensure that they could get a conviction against Bob, the police didn’t bother to get a warrant for Bob’s house where they found child pornography, and the prosecutor didn’t turn over evidence to Bob’s lawyer that the police actually found two sets of DNA at the crime scene. Bob maintains his innocence and the case relied on these pieces of evidence, but it’s very possible—even probable—that Bob did it.

Is a judge that is about to run for state Supreme Court going to give Bob the benefit of his constitutional rights even if it means his opponents will run an ad that the judge is soft on child predators? Under my hypothetical, Bob should have his conviction thrown out on appeal. Is our candidate judge going to run the risk that Bob commits another crime after he’s been released?

Let me change the hypo. Bob is now tried and convicted for sexually assaulting a minor, but the minor was 15 years old, Bob was 19, and they got married while the case was pending. Will the judge who is running for reelection think that he can show leniency to Bob during sentencing even though his opponents aren’t going to bother to mention the details of the case in their attack ads?

Outcomes don’t matter nearly as much as process when it comes to the law. But political accountability isn’t built for process. Judging is meant to be as countermajoritarian as it comes. We let 10 guilty men go free to ensure an innocent man doesn’t wind up in jail. The rule of law is designed to stand up to the passions of the mob. But “I let 10 rapists go free” doesn’t make for a very popular campaign slogan.

Speaking of process, it may also be worth noting that the primary in this race went the way that so many others have gone of late: Democratic groups spent $2.2 million running ads against the conservative candidate who was viewed as the most electable to give the eventual liberal candidate a better chance in the general election all while saying that the conservative candidate that won the primary is an election denier who is dangerous to democracy. Le sigh.

Here’s the bottom line: The outcome of this race tonight matters a great deal to the political future of Wisconsin. My point is that it actually shouldn’t.

Main Course

This bit of census journalism from Philip Bump at the Washington Post is worth a few minutes to marinate on:

Rural America is dying faster than it is producing new children. Census Bureau data released Thursday shows that, between 2021 and 2022, nearly 645,000 residents of rural counties died while only 494,000 were born.

The good news is that the population in those counties grew anyway — thanks to more than 163,000 new residents, almost certainly from more-populous parts of the country.

Or, put slightly differently: Red America is growing because blue America is shrinking.

All by itself, both of those facts (declining birth rates and blue → red migration) will have fascinating cultural effects in the long term. But the political effects may be greater in the short term because of all the things we don’t yet know.

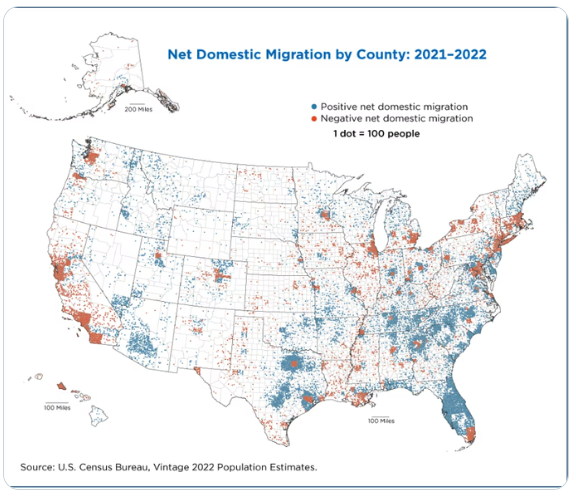

This visual representation may help highlight the issue:

First of all, imagine reapportionment after the next census. In 2020, Texas, Colorado, Florida, Montana, North Carolina, and Oregon all gained a seat in the House (Texas gained two) while California, New York, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia all lost a seat. Or to put it another way, redder states (Texas, Florida, Montana, North Carolina, minus Ohio and West Virginia) picked up three seats and bluer states (California, New York, Illinois, Michigan, Pennsylvania, minus Oregon and Colorado) lost three seats. That’s already a pretty clear trend, but if this continues, the House of Representatives will be even more skewed toward Republican states based only on population after 2030.

Of course, this gets interesting because the Electoral College is based on these numbers (two Senate seats for each state, plus the state’s number of House seats). In the past, Democrats disfavored things like the Electoral College and Senate representation because it was anti-majoritarian. Why should Wyoming have three votes for president when the entire state has the population of Baltimore? But as the population shifts toward red states, the politics behind that argument may shift as well.

But this brings us to the second issue. Nobody knows how these transplants are going to vote. They moved for a reason. But if San Francisco-types move to Austin, are they going to keep voting like they’re in San Francisco? I find this fascinating because I’ve always considered myself an economic conservative and a social liberal (technically, a civil libertarian but tomAto/tomAHto). I always assumed the vast majority of Americans were EC/SLs but that some of us prioritized one side of the other and it was just that darn two-party system that prevented us from finding one another. Boy, was I wrong.

This doesn’t perfectly capture my politics, but it’s pretty clear I’m in the minority all the same.

So let’s go back to our San Francisco → Austin friend. One could easily imagine that this person moved for better job opportunities, so that perhaps they appreciate a no state income tax paradise like Texas but it won’t change any of their views on, say, trans issues. That’s my economically conservative/socially liberal buddy, but like I said, there’s just not a lot of evidence there are many of those people out there. Perhaps instead he moved for his job and never gave it much thought as to why the job existed in Texas and not California. He thinks it’s bizarre that Texas doesn’t have an income tax and that everyone is running around with guns and cowboy boots. He’ll keep voting like a Californian and the Beto O’Rourkes in Texas get a boost next time around. Or perhaps the opposite happens and our friend has the zeal of the convert, marries a Texan, and learns everything he can about our “come and take it” history. He was one of those outcast Republicans in California who has finally found his people in Texas.

Regardless, this isn’t just politics at play. It’s also a post-COVID shift as more people are able to work remotely. Not only do those people move away from high density cities, but other jobs are affected as they stop commuting and working from a downtown office—dry cleaners, coffee shops, car repair. Now those people start thinking about building different lives too.

The point is this: The whole “more deaths than births” in these parts of the country means that people aren’t being raised into a specific regional or political culture. They’re moving to it. And like any other migration we’ve seen in American history, transplants are part assimilation and part transformation. It’s why pastrami is better in New York City and brats are better in Wisconsin.

It’s also why migration can turn red states purple.

Dessert

My 2.5-year-old son is in the phase of asking us to define words for him. It’s harder than you think. Yesterday, I was asked to define “independent” and “question.” He literally said “what is a question?” To which I said, “You just asked one!” And then I got a blank stare …

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.