Campaign Quick Hits

Voting Laws Don’t Matter Much: Well-respected Emory political science professor Alan I. Abramowitz has published yet another study that found that the types of voting restrictions pursued by GOP states–requiring voter ID and limiting drop boxes and early voting—“had only minor effects on turnout and no effect at all on the Democratic margin in the presidential election.” Instead, he found that “both voter turnout and voting decisions in 2020 were driven by the strong preferences held by the large majority of voters … increased use of absentee voting had only a small impact on turnout and no effect at all on the Democratic margin in the 2020 presidential election.”

In other words, Republicans are wasting their time if they think these laws are politically advantageous but also Democrats have no factual basis for believing these laws are “Jim Crow 2.0” or result in widespread “voter suppression.”

Quote of the Week: “The groups where Vance has improved are those we don’t want him doing better with: Trump disapprovers and moderate/liberals,” Tony Fabrizio in a 98-page polling report created for a super PAC that supports Republican Senate candidate J.D. Vance’s campaign in Ohio.

Love it or hate it, this is the playbook on how to win a GOP primary in 2022. This report will get read by every GOP primary candidate running in 2022—or thinking about it for 2024 because the polling reflects the effects of a $2 million ad campaign supporting rival Josh Mandel that showed “Vance describing himself as a ‘Never Trump guy’ and calling Trump an ‘idiot,’ ‘noxious” and ‘offensive.’”

I think the outcome of the Ohio Senate race will make or break a lot of 2024 campaigns. If Vance wins the primary, it will be seen as a model for how to tie a candidate to Trump without the full embrace. If Mandel wins the primary and wins the general election, I think several potential 2024 presidential candidates quietly shutter their fledgling campaign operations. If Mandel wins the primary and loses the general election, it will almost certainly mean that Republicans lost the Senate because of Trump (again). And it will send shock waves throughout the Republican establishment as a surefire indication that Trump has no shot at winning in a general election—no matter how badly Biden or the economy does.

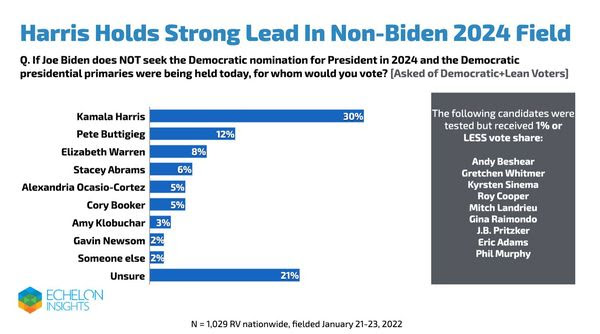

Speaking of Primaries: Check out this fun graphic from our friends over at Echelon. Let me be clear: This is in no way an indication of who the frontrunners would be if Biden doesn’t run. But like its GOP equivalent, it tells you who has name ID among Dem voters and who is getting the most attention from left-leaning news outlets. Given those inputs, I’m surprised Eric Adams didn’t get into that coveted 2 percent slot. And I’m even more surprised that Gavin Newsom did.

Stuck in the Middle Without You

“Without moderates, this place will be almost unworkable,” says GOP Rep. John Katko of New York. And yet that’s exactly what seems to be happening. Audrey Fahlberg and Harvest Prude have the latest in a full-length piece on the website:

Per data compiled by the Brookings Institute, the number of House members who carried districts won by a presidential candidate from the other party—known as “crossover districts”—averaged well over 100 members for the 40-year period beginning in 1956. That number has shrunk every presidential election cycle since 1984, when 190 members—or 43.7 percent of the House’s 435 members—were elected in crossover districts. In 2020, that number fell to 16—just 4 percent of the entire lower chamber, per FiveThirtyEight’s Geoffrey Skelley.

Democrats have experienced the trend more over the past two decades. “As recently as 2008, there were almost 50 Democrats who won the districts that John McCain carried for president,” said Sabato’s Crystal Ball election analyst Kyle Kondik, down from 86 in 2000. “In this most recent election, there were only seven [crossover Democrats]. Redistricting will sort of shuffle those numbers a little bit, but you’re just seeing a decline really on both sides of members being able to hold these districts that aren’t otherwise favorable to their party.”

Increased polarization among voters from both parties has also exerted downward pressure on moderates to either abandon their bipartisan instincts or leave Congress entirely rather than risk tough reelection battles come midterm season.

You can read the rest here.

McCain-Feingold Ruined America: Mailbag Edition

I read all the thoughts and feelings in the comments section of this newsletter every week. (Thanks, btw!) And while I try to take questions into account for the following week, I’ve never done a true mailbag edition.

But one of you sent in four questions on my thesis that the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2001, better known as McCain-Feingold, is directly responsible for the dismal state of our current politics—the extremism, the norm-breaking, the death of Congress as a legislative body, etc etc.* Here’s the gist of my magnum opus:

1. The ban on “soft money” weakened the national parties.

2. The low limits on individual federal donations disincentivized major donor programs and incentivized the money to come from elsewhere.

The contribution limit was indexed to inflation—but not the inflation of campaign expenditures. My first campaign was in 2002 and the limit was $2,000. But the range for contributions from individuals in the top 50 House races in 2002 was $1 million to $3 million. In 2020, it was $5 million to $28 million. So while the donation limit is 1.5 times higher, the amount of money you need to raise to stay competitive is six to nine times more. What is a candidate to do?

Campaigns on both sides have gutted their “major donor programs” and beefed up their online and digital fundraising. The cost per dollar raised is substantially higher, but it doesn’t take any of the candidate’s time—a campaign’s most valuable resource—and the candidate doesn’t have to dial for dollars for eight hours a day, a task that very few candidates are willing to do without grumbling, procrastinating, or other tactics used by teenagers to get out of geometry proofs.

Only 3 percent of voters are ever going to give to a candidate (and that number gets lower the lower down the ballot you go). So how do you reach them? And how do you motivate them? Outrage.

So here goes our Q&A:

1. BCRA passed in 2002, but this phenomenon seemed to only become an observable problem 14 years later in the 2016 elections. To me, this timeline trends more closely with the rise of social media and increased sophistication in digitally informed databases of online users that can be precisely targeted with narrowly-crafted messages in a way that wasn’t possible before everyone lived most of their waking lives online. How much blame would you attribute to technology advances? Seems to me like BCRA isn’t the culprit for these shifting incentives, Facebook is.

Great question. Reliance on small dollar/online donations isn’t possible without the technological advances—and our reader is clever to point out that it is both social media and tracking technology that allow this to happen. But my point is that reliance on small dollar/online donations also isn’t likely without the incentives that BCRA put in place.

And we can test this theory because plenty of states don’t have BCRA-esque limits for their governor’s races. Pennsylvania, Texas, and Virginia don’t have limits on how much an individual can contribute in a state race. So in Texas, Greg Abbott’s no-limits gubernatorial campaign got 159,000 contributions and the average was just more than $119. Ted Cruz’s Senate campaign—regulated by the federal limits on donations—still got 120,000 contributions but the average there was only $37.

Clearly, then, the federal limits themselves—and not just the technology—are driving the fundraising strategy toward online donors.

2. Your premise also assumes that candidates have little incentive to cater to uber-wealthy donors because their fundraising potential is capped at just a few thousand dollars each. But then you don’t really explain the impact of independent expenditure PACs and 501(c)4 groups.

True! Federal candidates can and do still court big donors in the hopes that they’ll give $10 million to a super PAC to support their candidacy. The candidate doesn’t control that money—the super PAC can’t ask the campaign whether it makes more sense to run an ad on immigration or crime next week. There are other—legal—ways that the campaign can tip off the super PAC, as I’ve discussed previously. But even a misspent $10 million supporting your candidacy is better than no $10 million. So then does BCRA even matter?

Yes, for two reasons. First, the campaign still needs some source of funding. The super PAC can’t do it all, and so if the campaign needs to raise money, we’re back to my original point, which is that the online donor tail is wagging the candidate dog. And even more so, that the online donors are in fact dictating not just who wins—but who is even willing to run in the first place.

Second, the super PAC dollars are less effective because of all those anti-coordination rules. So the way I think about it is that a super PAC dollar is worth about 20 to30 percent of a “hard dollar.” (Hard dollars are the industry term for money raised under the federal limits.) I don’t know a candidate alive who wouldn’t gladly get rid of super PACs in exchange for no limits and immediate disclosure rules. Citizens United, which I think was legally correct but politically detrimental, could be renamed the Political Consultant Full Employment Act of 2010.

3. Even if you’re right, what would be your alternative? Remove all campaign donation limits? Are the incentives any better when just an elite, insulated, unanswerable, wealthy few are driving electoral (and thereby policy) outcomes? Is having Peter Thiel determine the next senator from Ohio that much better than having tens of thousands of radicalized, manipulable Republican “base” donors throwing in $100 each?

Fair question. I’d go to the Virginia/Pennsylvania/Texas model of no limits, full disclosure. Clearly, those governor’s races aren’t paragons of virtue harkening back to our softer, gentler days. But, then again, I actually think the Virginia governor’s race we just had was actually less radical than the 2020 presidential race in every respect. So I don’t know. But this ain’t working.

4. As a corollary to the previous question, isn’t voter perceptions about their elected officials being beholden to wealthy, well-connected elites (and largely ignoring the concerns of their rank-and-file constituents) kinda what got us Trump (and the overall rise in populism within both political parties) in the first place? If we’re really trying to restore trust in institutions, wouldn’t the remedy be more campaign finance regulation to compel disclosure of (c)4 donors and complete, documented, verified transparency on elected officials’ sources of income, donor identities, assets/investments/holdings, tax returns, and accountability that links every dollar spent in a campaign to the specific name of the person who paid for that expenditure (and should be accountable for what it says)? Why is less popular accountability in campaign finance a better alternative to more transparency in campaign finance if the underlying problem is a lack of institutional trust?

Why are all you readers so smart? Ugh. Yes, clearly these are all good points and like so many things, I think I’m right … but I don’t know I’m right. I think money in politics is like water and it will always find a way. Tighter regulations, then, won’t help—it’ll just force the water toward a different, less predictable crack with its own unknown and unintended consequences. Whereas, I know what no limits, full disclosure looks like because we do it in 11 states right now.

And I don’t agree that this is “what got us Trump.” I agree it’s what Trump voters say got us Trump. But the rise of populism is happening internationally. To me that signals that this is more about the 2008 financial crisis than anything specific to our domestic political moment. Plus, “running against elites” is a tale as old as time—or at least Andrew Jackson.

That being said, if we got rid of limits, I agree we’d want full and immediate transparency far beyond what we have now. No secondary distributions above $10,000 in which the campaign pays the law firm $1,000,000 and the law firm then pays 50 different political consulting businesses to do various shady things. And a rule that a campaign has 24 hours to post every new donor. Regulate the disbursements and the disclosure, not the contributions.

*Correction, February 8, 2022: Because of an editing error, a phrase was omitted from the original version of this piece. It should have read, “the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2001, better known as McCain-Feingold, is directly responsible for the dismal state of our current politics …”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.