Welcome back! As I mentioned last week, we are spending the next few newsletters giving you the first look at the possible field of the 2024 Republican presidential primary.

Last week, we covered four Senators: Hawley, Cruz, Cotton, and Scott. A few of you (a full stampede, actually) complained that several senators were left off the list. What about Florida Senator Rick Scott, who seems to keep popping up in Iowa? Florida’s other senator Marco Rubio, “The Republican Savior”? Nebraska senator and Trump skeptic Ben Sasse?

Here’s what I have to say to that: Sure, any of those guys could run too. I think the idea of Florida having all three top electeds—the governor (see below) and both senators—running is insane, making it all the more likely to happen. The 15-plus candidate batch we are covering isn’t comprehensive, but it is the list of candidates I’m most interested in watching and whose candidacies could change the trajectory of the race as a whole. Plus, I reserve the right to revisit our candidate list repeatedly over the next … 29 months.

Next week, we’ll take on former Trump officials like Mike Pompeo and Nikki Haley, and later we’ll get to the moderates such as Larry Hogan and Chris Christie—plus our celebrity bracket with Tucker Carlson and Dave Portnoy. But this week, we’ve got …

The Governors

Ron DeSantis: The Frontrunner

42 years old, Governor of Florida

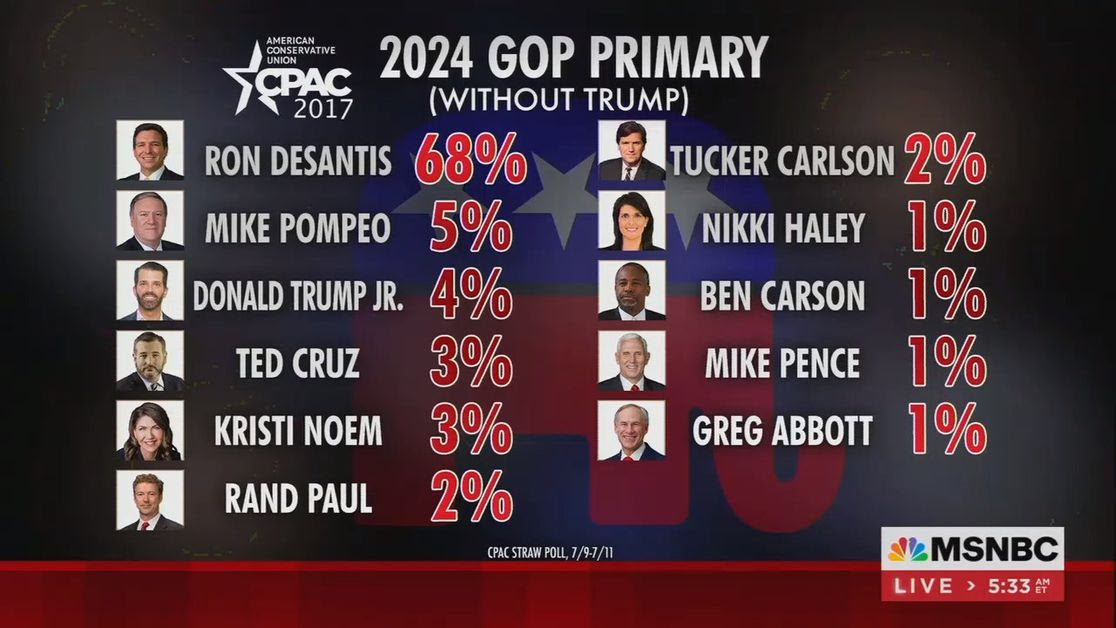

Here’s the central piece of current 2024 conventional wisdom in four words: If not Trump, DeSantis. Despite plenty of Republicans eyeing the top prize, the inside track is currently occupied by the former Florida congressman and current Florida governor, who has steadily built a reputation on the right as the sort of “Donald Trump, without the baggage” leader right-wing pundits and politicos have spent the last few years proclaiming will be the next evolution in GOP politics. Last week, the Conservative Political Action Conference in Dallas asked its attendees who their pick would be for president in 2024 were Trump not to run again. DeSantis collected 68 percent of the vote; nobody else got higher than five percent.

In the modern Republican party, a successful leader is one who can move effortlessly from the flash of culture-war pyrotechnics to the grind of actual government work, and DeSantis has shown himself to be a force on both fronts. In 2018, he knocked off the Republican establishment’s primary pick for governor on the strength of a brand he built defending President Trump from Russia-related allegations on Fox News. Even as governor, he’s never shied away from confrontations with the media—particularly after he became a liberal villain for his relatively laissez-faire handling of COVID-19.

But the spotlight resulting from DeSantis’s appetite for controversy has revealed him to be a canny political operator, too. In recent months, DeSantis has won Republican plaudits for his stewardship of a number of new laws and executive orders designed to please a culture-war-happy base: a ban on vaccine passports here, a ban on biological males in girls’ sports at public schools there, a rule preventing public schools from teaching critical race theory shortly after. Last month, the governor issued a blanket pardon for any Floridians who had violated anti-pandemic measures.

Strengths: He’s leading every poll of GOP primary voters, benefited from a failed 60 Minutes hit piece that was debunked by Democrats in his state, and was relentlessly attacked for opening Florida’s economy too early during the pandemic—only to have remarkably similar outcomes in both death and infection rates as California.

Weaknesses: Everyone who knows him will tell you that he is going to have problems with the retail politics required in Iowa and New Hampshire (read: he’s a jerk), he has to win reelection in 2022, Trump thinks DeSantis owes him and his ego will require a lot of care and feeding (read: groveling) between now and 2024 if DeSantis wants to prevent Trump from trashing him, and frontrunner status comes with a target on your back.

2024 Tea Leaves: The frontrunner tends to run … but feel free to ask President Scott Walker or President Tim Pawlenty how it can turn out.

Greg Abbott: The Other Governor

63 years old, Governor of Texas

Abbott has been a lawyer, trial judge, Texas Supreme Court justice, and Texas attorney general. He has used a wheelchair since the age of 26, when an oak tree fell on him while he was jogging, leaving him paralyzed from the waist down. In 2018, he was re-elected Governor with 42 percent of the Hispanic vote—seven points higher than Ted Cruz that same year.

He knows illegal immigration can be a winning issue for him. He recently announced “his plan for Texas to build its own border wall, starting with the hiring process for a program manager and providing $250 million in state funds as a ‘down payment.’” This came after he asked other states to send help, prompting Georgia, South Carolina, Oklahoma, Arkansas, North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa and Florida to answer the call. And he deployed the Texas National Guard and state troopers to “arrest immigrants and charge them for state laws such as trespassing, illegal entry, smuggling and human trafficking.”

Abbott called a special session for the legislature this summer to take up bills on election reform, critical race theory, and tech censorship—topics which have the makings for a tidy stump speech. And now that Democrats have chosen to flee the state in a couple private jets to D.C., Abbott is teed up for some national attention with some easily caricatured villains.

Strengths: Texas is a big state with some of the biggest GOP donors and all different stripes of Republican primary voters, he’s shown an ability to attract headlines that appeal to GOP base voters, and he faces a clownish gubernatorial primary challenge from former state party chair Allen West, which has the chance to make him look stronger.

Weaknesses: He’s been overshadowed by DeSantis so far, has no political experience in a purple state and very low name ID, is not a compelling speaker, and is known for trying to hang back to read political winds before wading into controversial issues.

2024 Tea Leaves: Rumor has it that Abbott’s team has already begun reaching out to Iowa operatives. Trump’s former rapid response director moved to Texas ostensibly to help with Abbott’s re-election in 2022.

Kristi Noem: The Smarter, Stronger Sarah Palin

49 years old, Governor of South Dakota

It’s hard to summarize Noem’s position in the 2024 field better than Jonathan Martin did in the New York Times: “If Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida is widely seen as the brash heir apparent to Mr. Trump, and senators like Josh Hawley and Tom Cotton are attempting to put a more ideological frame on Trumpism, Ms. Noem is trying to cement her place as the only female Trump ally echoing the former president’s trigger-the-left approach among the upper tiers of potential 2024 candidates.”

Since her election in 2018, Noem has worked tirelessly to raise her profile and tie herself to Trump. She went so far as to present him with a 4-foot replica of her state’s claim-to-fame, Mt Rushmore, with Trump himself featured next to Lincoln and Roosevelt. This fueled speculation that she was hoping to replace Mike Pence on the ticket in 2020—a rumor that was taken so seriously that she flew to Washington to privately assure Pence that she had no vice presidential ambitions.

For now, Noem is touting her reputation as one of America’s most hands-off governors during the pandemic—pushing against mask mandates, economic shutdowns, and the like from day one until the present. As she put it at CPAC, South Dakota under her leadership was the “only state in America that never ordered a single business or church to close.” These policies came with a cost—South Dakota has been third-worst in the country in COVID cases per capita and tenth-worst in COVID deaths per capita during the pandemic.

Strengths: She made a big splash at CPAC, with the Independent calling her “the smartest and most dangerous force in the country” and CNN labeling her “the female incarnation of the 45th President,” she speaks GOP base about as well as anyone in the field, and she’s shown she can get attention from media on the left and the right.

Weaknesses: Very few people outside of grassroots activists know who she is, she’s running a small state in terms of population and a very rural one, which will make it hard to argue that any of her policies or successes as governor can translate nationally, and Republicans love to root for a Sarah Palin type but we haven’t seen any evidence that they want to vote for one.

2024 Tea Leaves: She’ll be in Iowa later this month. Corey Lewandowski, the President’s former campaign manager, is advising her. It’s a done deal.

And The Winner Is …

No, the CPAC straw poll isn’t scientific. But it does tell us what an influential group of GOP grassroots activists are thinking. And the message is clear:

Operative View: Early States Matter

I got in touch with Dave Kochel, who advised Jeb Bush in 2016, to ask him what potential 2024 candidates should be doing right now.

Focus everything on ’22. Congress is within reach, and if you’re not trying to flip it, you’re not able to claim that you were doing everything possible to stop the Biden/Harris agenda.

Tactically, early states still matter (I’m sitting in Iowa as I write this lol) because you have to have a place to hold the show for the cameras. Lots of good races here to road test a midterm message around pushing back on the left.

No overt organizing yet, there’s time for that later and Trump’s looming presence over the potential field suggests it’s better to keep your head down while he decides what he’s doing.

Spend on digital now, build a file, all under the mission of ’22 and flipping Congress.

That’s about it.

Oh, and get on Fox. Still gotta be famous with the base.

We talk a lot about grassroots donors and heavy hitters in this newsletter, but what about the corporations that spend millions on elections each year? Chris has some thoughts:

Toyota’s Blind Spot Shows Way Forward on Campaign Finance

With the rise of celebrity candidates, social media lowering barriers to entry, weak parties, and small-dollar online donations, one would think that we had finally moved beyond the old discussions around campaign finance reform. Alas, we have not. The For the People Act backed by almost every Senate Democrat includes provisions for publicly financed elections, and similar efforts are underway on the state level.

Most of these programs work from the assumption that big-money donors are corrupting the political process. While it’s certainly true that cash-starved politicians can become beholden to mega-donors, it seems like more of our problems these days relate to the corrupting influence of small-dollar, rage-click online donations. Plus, if recent decades have taught us anything, it is that special interest and corporate money will always find a way into the system. In fact, well-intentioned but bad bills like McCain-Feingold often end up distorting the market for contributions and reducing transparency. What does work, though, is accountability. And a recent episode illustrates how.

Citizens for Ethics and Responsibility in Washington, a left-leaning watchdog group, came out with a report a few weeks ago on corporate political action committees that contributed to the 147 congressional Republicans who voted on January 6 to try to block President Biden from taking office.

The watchdog group padded its numbers by including the House and Senate GOP campaign arms in the list of corporate donations made since the deadly pro-Trump mob stormed the Capitol in support of members trying to subvert the election results. The National Republican Campaign Committee and the National Republican Senatorial Committee also back the Republicans who didn’t try to steal the election. Eighty-eight percent of the nearly million dollars in contributions were to the committees, not the individual members who backed Trump’s bid to remain in power. But if the group’s position is that the Republican Party is itself seditious, that’s their call.

However they sliced it, though, one story came through clearly: Toyota’s PACs had given far and away the most money to individuals—$57 thousand—and donated to the largest number of individual members—38—than the committees of any other corporation. The real surprise, though, came when Toyota USA bucked the immediate pressure it faced for the dubious donations. The automaker told Axios it would be wrong to “judge members of Congress solely based on their votes on the electoral certification.” The donations had been reviewed, Toyota said, to exclude “members who, through their statements and actions, undermine the legitimacy of our elections and institutions.” But they still gave money to this guy? Gotcha.

It might seem strange that a Japanese automaker would be so monosugoku MAGA, unless you understand Toyota USA as a predominantly Southern enterprise. Its headquarters are in the Dallas suburbs, and with the exception of some operations in Michigan and California, its plants are all in red states. Toyota was an early adopter of moving production for the American market to the U.S. and focused on the South and Appalachia where they found several favorable things: right-to-work laws and a generally weak union presence, lower wages, and politicians eager to offer fat incentives to land manufacturing jobs. And that’s still going on today. Toyota was telling the truth: the PAC donations weren’t about supporting the riot or stealing the election. They were about getting porky goodies for a company that relies a lot on government assistance.

That ended last week, when the company put out a statement saying that there wouldn’t be any more contributions for members of Trump’s wrecking crew. This was not surprising. It’s bad business to be associated with radicals like Biggs, and we can be sure that the crazy-cakes behavior from him and other recipients of Toyota PAC money will continue as the 2022 cycle heats up. The pressure worked, and Toyota threw its government benefactors right under the wheels of its RAV4.

Many states, including the Grand Canyon State, offer versions of publicly funded elections like the one Democrats are seeking nationally. But would lawmakers like Biggs be more or less accountable if they got their campaign cash from taxpayers or from Toyota? Publicly funded campaigns aren’t just an incumbent-retention device but also another way to insulate lawmakers from accountability. If you pair public funding of campaigns with an allowance for small-dollar donations, you get strong incentives for loony behavior and fewer ways to punish bad actors.

As Toyota’s reversal shows, transparency allows for accountability, and accountability is what we’re really looking for. If groups like Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington do their job and we in the press do ours, we won’t stop the corrupting influence of money or keep donors from backing shady politicians entirely. But as long as there’s a real chance for consequences, they’ll at least have to think twice about it.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.