Campaign Quick Hit

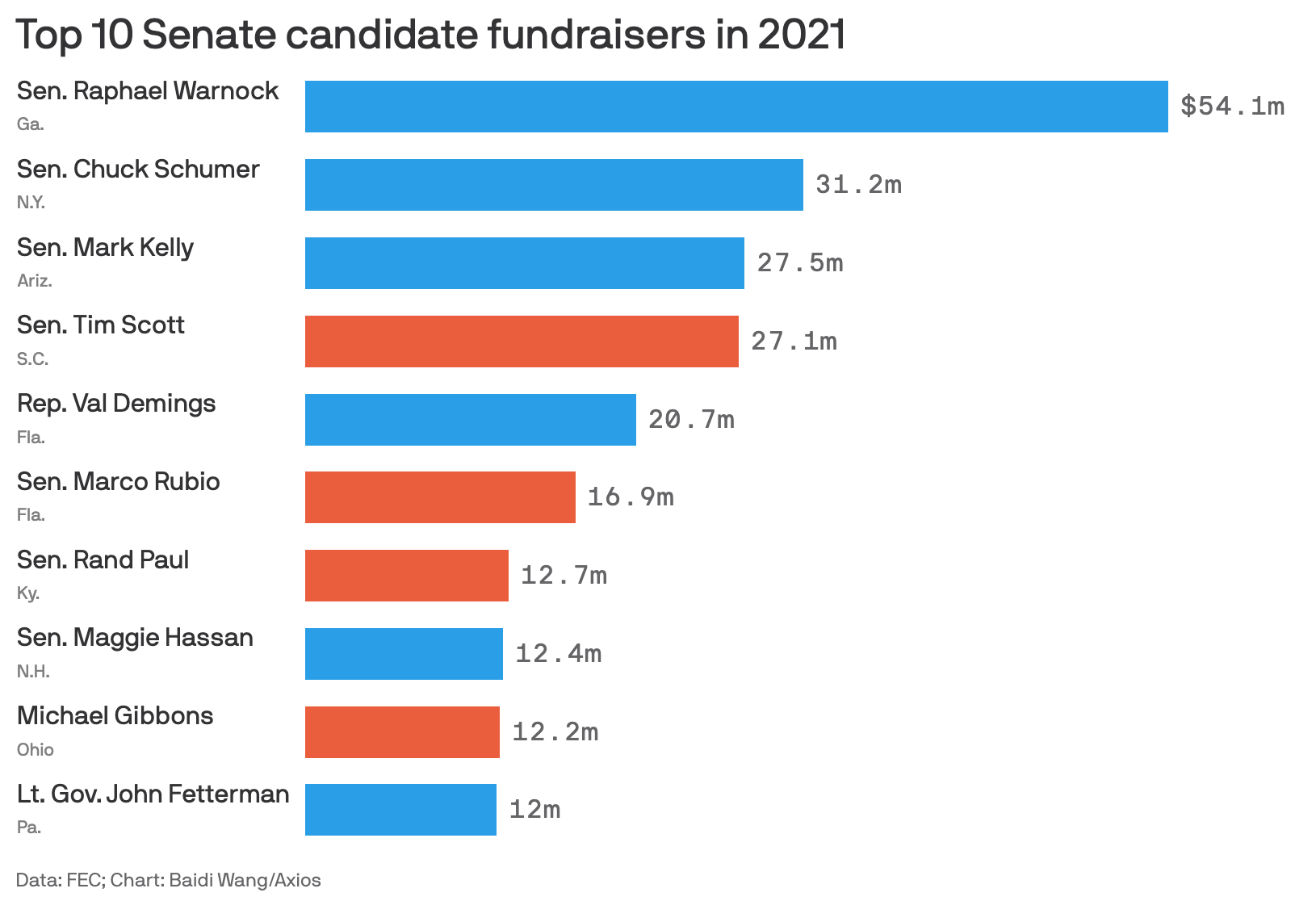

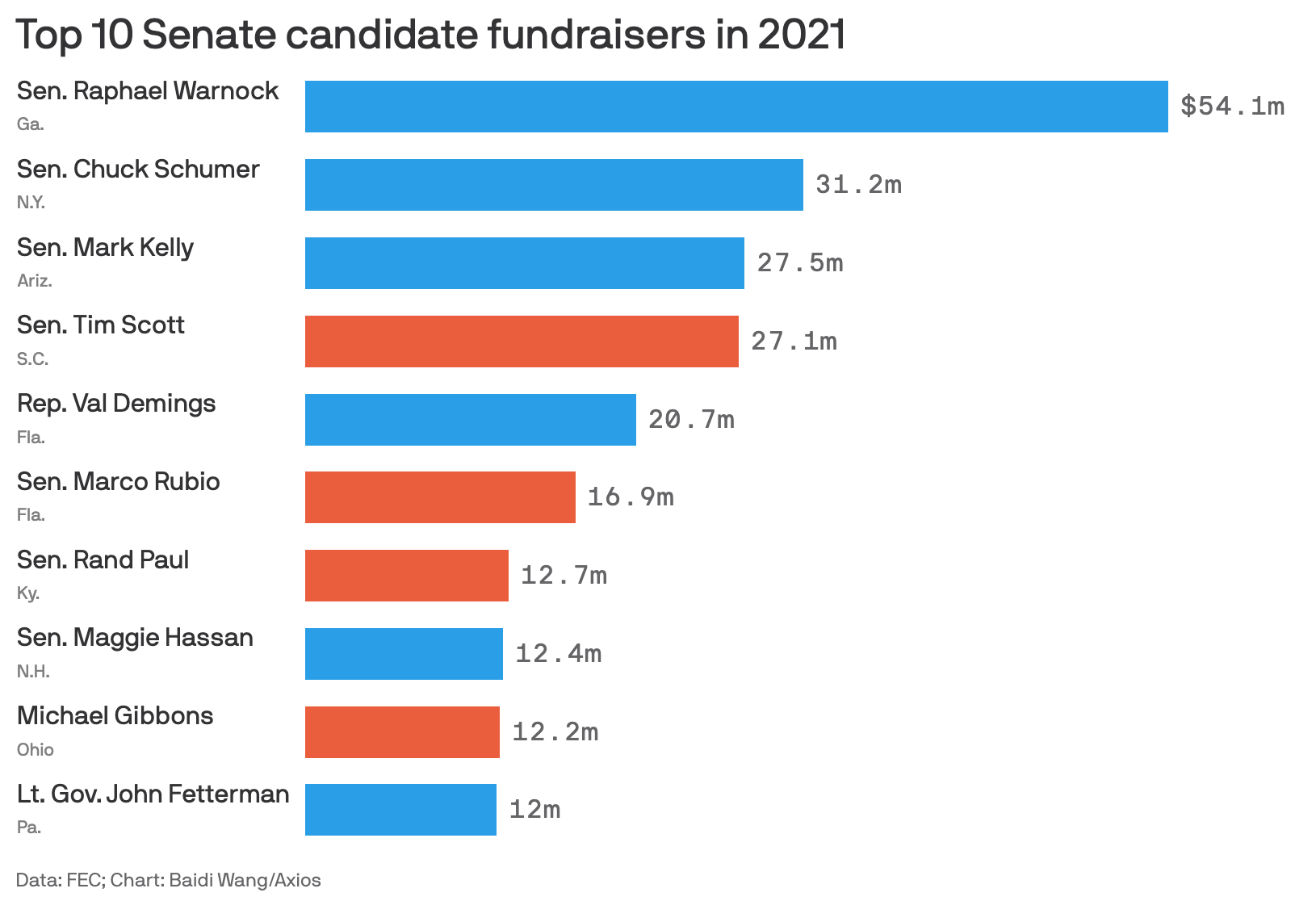

What Does Money Mean: I’m focusing most of this week’s newsletter finishing our deep dive into issue advocacy politics, but figured I should include these charts that have been making the rounds headed into 2022:

If you had shown me these numbers in 2002, I would tell you they are going to map onto who will go on to win their races with amazing precision. Back in the day, the candidate who raised the most money nearly always won. As it turns out, though, money is necessary but not sufficient. Once a campaign has enough money, the returns on election turnout diminish quickly for amounts over that.

It is impressive that Sen. Raphael Warnock is the top fundraiser in the Senate, but it tells me next to nothing in the modern era about how he will do against Herschel Walker in November. Ditto Mark Kelly in Arizona. And even if we assume that money can serve as a stand-in for voter enthusiasm, the proliferation of online, small-dollar fundraising means that we’d need to take a much closer look at in-state vs. out-of-state dollars coming into these campaigns.

The biggest takeaway for me is who is on this list who shouldn’t be. Sen. Tim Scott isn’t in any danger of losing in South Carolina, and yet there he is. This will make him one of, if not the, most coveted speaker and fundraiser for other GOP candidates in 2022. It also sets up Scott nicely for his own presidential run in 2024—and makes him the runaway favorite for the VP slot if Trump runs.

And then there’s Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Marjorie Taylor Greene. These are candidates who have mastered turning media attention and criticism into fundraising dollars. They may be backbenchers without any real legislative power, but their fundraising abilities give them sway within their parties because, as I’ve noted before, candidates rely on renting each other’s email lists, which means having a big, productive list can mean more power in 2022 than being a committee chairman in a legislative body that doesn’t legislate anyway.

Another thing to note about these data is that these are only the candidate PACs and not leadership PACs or super PACs, which for folks like House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer means that you’re only seeing a narrow sliver of the full story.

What’s the difference and why does it matter? We’ll save that for next week and it will answer the question: If he knows he’s running, why hasn’t Donald Trump declared his candidacy for 2024?

The Chicken and the Egg: Part 2

Before we dive into my Q&A with Josh Balk, vice president at the Humane Society, about his successful work on the cage-free ballot initiatives, there’s one anecdote that summed up for me why Josh has been so successful where so many other issue advocacy groups have failed.

In 2008, California was going to vote on a ballot proposition to ban same-sex marriage. As many of you will remember, Prop 8 attracted a ton of media attention as well as money from across the political spectrum. But there was another measure on the ballot that fall. Proposition 2 asked voters to codify minimum space requirements for veal calves, breeding pigs, and egg-laying hens. At one point, the gay marriage advocates who were opposed to Prop 8 offered to combine forces with Josh and his team to bundle Prop 2 with Prop 8. It would have guaranteed access to more money, more boots on the ground, and more attention from the mainstream media.

Josh said no even though, at the staff level, the two teams were no doubt ideologically aligned. He understood that staff alignment wasn’t the same as voter alignment. And it’s not obvious that a voter who supports a ban on gay marriage wouldn’t also want more humane treatment for farm animals. So Josh turned down the help. Prop 8 passed—banning gay marriage—with 7 million votes. And Prop 2 passed too … with 8.2 million votes.

Josh’s instinct was right that there were voters on both sides of the gay marriage issue who could be persuaded to help animals. If he had joined forces with the anti-Prop 8 team, it would have made his ballot measure a proxy in the bigger, partisan culture war question. Instead, Prop 2 stayed about animals and voters were able to vote for the issue and not for their tribe.

The best operatives are the ones who are able to see outside of their own experience, partisan cheerleading, and Twitter feed—and put themselves in the shoes of the voters they need to persuade. It’s hard, and it’s rare.

In 1854, Abraham Lincoln gave a speech in Peoria, Illinois—to persuade his audience of the moral case against slavery—that stuck in my head as I was talking to Josh:

Before proceeding, let me say I think I have no prejudice against the Southern people. They are just what we would be in their situation. If slavery did not now exist amongst them, they would not introduce it. If it did now exist amongst us, we should not instantly give it up.

When I asked Josh about working with the industry responsible for the current caging practices, he said, “They didn’t invent the caging of chickens, but rather they continued the practice since it became the norm in the egg industry to do so since the 1960s. If I was born into the egg industry and carried on the production practices that my father taught me, perhaps I would’ve done that too.” Sound familiar? It is this empathy for one’s opponents that I’m convinced allows the great operatives to beat their opponents—and yet it is exactly the opposite of what we see in most political debates today.

So here’s more of my conversation with Josh:

Sarah: The cage free egg movement isn’t viewed as a particularly partisan issue like climate change or gun ownership. But it could have been. Teaming up with a political party can bring a lot of attention and salience to an issue. It can mean access to donors, members of Congress, White House staff. Of course, it can also lead to culture war-driven gridlock as people dig in with their tribe. When you first sat down to plot your strategy, how did you think about those tradeoffs and which route did you take?

Josh: I’ve always believed that whether someone is a Republican, Democrat, or independent, if you want to help animals have a better life, you’re on the team. Preventing cruelty to animals goes even beyond a non-partisan issue; it’s a human issue. I think of a dad who loved his dog, considered her a member of his family, spoiled her rotten, and at the end of her life, he cried with his kids when they had to say goodbye. There’s no way to know which political party the dad identifies with. And that’s the point. Why start having a litmus test on political beliefs when helping animals should welcome everybody?

Here’s how we did it. If we used the strategy of past decades, we perhaps would’ve tried over and over again to pass legislation through state legislatures. Our cage-free legislation would be assigned to the agricultural committee. No matter the state, typically this would be a committee whose members were financially backed by the very industrial operations we were looking to reform, and thus it was virtually impossible to get anything passed. So our bills wouldn’t even have a chance to be considered by the entire state legislature since they’d be stopped in committee. Rather than going down this tired and ineffective path where only a few politicians could block immensely popular support for animals, we instead went directly to the people by waging ballot measure campaigns.

Once that decision was made, the question we faced was what we should specifically ask for in the measures. It’s always a balance between trying in one fell swoop to eliminate all suffering farm animals face inside industrial facilities, while simultaneously not being too far-reaching to lose mainstream support. We came to the decision that if we focus on getting farm animals out of cages, it would be so common sense that we’d get vast support. And of course, this wouldn’t ensure utopian conditions but at least freeing egg-laying chickens (as well as mother pigs and baby veal calves) from cages, it would decrease a massive amount of intense suffering for an extraordinary number of animals.

We knew when waging our ballot campaigns, we needed a simple message that would resonate with the average voter. Whether in debates, TV commercials, editorial board meetings, or speeches, the message was consistent and strong: All animals deserve humane treatment and it’s cruel and inhumane to confine a chicken in a cage so small she can’t even spread her wings. No matter what silliness the opposition could throw our way, we never wavered in our core message.

This formula allowed us to wage ballot campaigns in red states, blue states, and purple states, with the outcomes being nearly identical; landslide votes in favor of freeing chickens and other farm animals from a lifetime of cage confinement.

Since the ballot campaigns were so high-profile and won overwhelmingly, state legislatures and the egg industry itself came to the conclusion that it’s better for them if they negotiate with us. These discussions led to agreements where we’d give the industry a bit more time to shift to cage-free if they’d endorse cage-free legislation. It was through these agreements that even in state legislatures where political animosity often flairs hottest, we’ve passed cage-free laws in supermajority Democratic states like Massachusetts, supermajority Republican states like Utah, a Republican statehouse with a Democratic governor in Michigan, and a wide variety in between.

Sarah: Part of your success is that the big egg producers want to work with you now after years of being on opposite sides of this issue. But that means compromising as well—longer timeframes for when all eggs will be cage-free and the definition of cage-free. It’s easy to say, “don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.” But how do you know where that line was between good and perfect? How do you trust their side when you know they aren’t morally with you? Was it hard to convince your own side that you were now in the “good” territory when I assume at least some people thought perfect was within reach if you just kept pushing a little longer?

Josh: When negotiating with the industry to find common ground on legislation, what they’ve understandably asked for is a clear cage-free standard to follow—since they’ll be spending millions of dollars to convert to certain cage-free systems—and a phase-in process so they have the time necessary to convert. Over the past several years this collaborative approach has led to cage-free laws being passed in California, Oregon, Washington, Michigan, Colorado, Nevada, Utah, and Massachusetts.

It’s never easy to truly know the counterfactual of what would’ve happened if we refused to engage in talks with the industry and kept waging adversarial campaigns. And I understand if some feel like giving an industry several years to convert to cage-free is too long of a timeframe. I have to look at the results though.

Just from 2008 when we waged our first ballot campaign for chickens, through today, the egg industry has shifted from about 3 percent cage-free to now 34 percent cage-free. (According to the USDA, we’ll be at more than 70 percent cage-free in just a few years.) In terms of number of animals affected, there have been about 340 million chickens who lived cage-free during that time who otherwise would’ve been caged if it wasn’t for these advancements. It may be the greatest amount of farm animal suffering ever reduced in our country’s history.

For the chickens, this strategy is winning. What a strange confluence of events that it’s from us and the egg producers working together—rather than against each other—that’s changing the industry forever.

Sarah: I also think it’s interesting to compare this to similar efforts that didn’t work or that hit a high-water mark and fizzled out. Why do you think the cage-free movement has succeeded where, for example, the foie gras bans didn’t? The number of people in the country who have ever or will ever eat foie gras is infinitesimal. Shouldn’t that have been a much easier lift?

Josh: I think one of the reasons why the caging of chickens really took off as an issue is because—unlike a high-end table treat like foie gras—eggs are such a common breakfast item. Because of this, it made it easier to get more attention and to galvanize the public to support campaigns to create better conditions for the animals producing the very food they’re eating.

I remember after announcing a cage-free egg policy with a major fast food chain, I asked the executive who led the internal deliberations why they came to the conclusion to stop using eggs from caged chickens. She told me her company could “never successfully defend keeping animals in cages to our customers.”

It’s this sentiment that’s allowed us to wage—and win—corporate campaigns on the caged chicken issue. We’ve successfully got everyone from McDonald’s to IHOP to Burger King to Kroger to hundreds of other food companies to commit to switch to exclusively using cage-free eggs. Since these companies purchase so many eggs, there’s an immense incentive for producers to transition to cage-free.

As the egg producers are making this shift, they’ve come to the conclusion that cage-free laws are actually beneficial for their economic sustainability. These legislative actions—codifying the corporate commitments into law by mirroring their phase-in date to reach 100 percent cage-free—create the certainty and confidence they need to make large-scale investments to cage-free production.

Having corporate campaigns align precisely with our legislative campaigns—and having each being so successful—has been a core reason for our success.

Sarah: There are plenty of studies out there that will tell you that Brown v. Board of Education did very little to end school segregation. The polling numbers on abortion have changed remarkably little in the 50 years since Roe but gay marriage is now widely accepted. And what I think we can take from that is that laws don’t drive political change in a pluralistic society. So what does drive that change, in your opinion?

Josh: I think the difference with these examples and what’s happening with the movement to provide farm animals better lives is this: We’ve never asked the public to change their mind. It’s inherent in most of us that we simply don’t want to see animals suffer. No matter what generation we were born into or demographic background, we have that natural sympathy in us since we were young.

Unlike many human issues and societal disputes, there was never really a debate whether farm animals should be confined in cages. The caging of chickens (and pigs) didn’t start because it was a popular idea in the public, but rather sectors in agribusiness that became more industrial following World War II.

What drove the successful change in the egg industry is that vehicles were developed to allow ordinary Americans to express the voice they already had for better treatment of animals. We allowed them to learn the realities of how the animals were being treated and gave them the power to make changes through voting in ballot measures, contacting their legislators, and calling corporate headquarters’ complaint lines.

This is why I feel so confident we’re going to keep building a more humane future. When given a chance to choose kindness over cruelty, most of us—no matter our age, race, religion, or even political party—would come to the same conclusion.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.