Welcome back to Techne! This week I have been watching Flour Power from Twin Cities PBS. I fully recommend this documentary on wheat farming in the Midwest, the flour milling industry, and the expansion of the industry.

Notes and Quotes

- The Senate passed the ADVANCE Act last Tuesday, aiming to accelerate nuclear energy deployment by reducing regulatory costs, offering incentives, and expediting licensing for advanced technologies, among other things.

- Apple announced it will indefinitely delay the rollout of its new AI features in the EU, citing privacy and security conflicts with the EU’s Digital Markets Act. The move will keep these technologies from being used by consumers in all 27 EU member states.

- Check out this fascinating X thread on the 10 great papers to expand your econ frameworks.

- The Canadian scientist Vaclav Smil recently explained what the energy transition away from fossil fuels would mean in practical terms. We would have to replace more than 4 terawatts of capacity in coal-and-gas-fired stations; substitute nearly 1.5 billion gasoline and diesel engines; convert all agricultural and crop processing machinery; replace more than half a billion natural gas furnaces; and find new ways to power nearly 120,000 merchant fleet vessels and nearly 25,000 active jetliners.

- A new report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies reveals that Chinese EV makers received at least $231 billion in aid over the past 15 years, primarily through tax exemptions. This comes as the EU has announced tariffs ranging from 17.4 percent to 38.1 percent on EVs imported from China.

- My AEI colleague Lynne Kiesling recently published a helpful Substack post addressing the challenges of data center electricity consumption. Joseph Polidoro’s piece on the site from back in March is also helpful.

- The IRS reported that up to 90 percent of the 1 million backlogged Employee Retention Credit claims show signs of potential fraud. The Employee Retention Credit is a refundable tax credit against certain employment taxes.

- In a recent piece for The Atlantic, Derek Thompson helpfully explores the teen mental health crisis, noting its prevalence with English-speaking countries: “Smartphones are a global phenomenon. But apparently the rise in youth anxiety is not. In some of the largest and most trusted surveys, it appears to be largely occurring in the United States, Great Britain, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.”

- A bill in the California Legislature proposes to mandate one employee for every two self-checkout stands in grocery and drugstores, potentially undermining the efficiency of self-checkout technology and disrupting consumer preferences.

- New York Gov. Kathy Hochul has signed the SAFE For Kids Act, which requires social media companies to limit addictive feeds for users younger than 18.

- A cyber incident affecting 15,000 car dealerships caused critical systems to go down for multiple days, severely disrupting operations.

The Haphazard Road to Rural Broadband

I recently got a message asking me what I thought about this Washington Times article by Susan Ferrechio on the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) program. As part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act signed in November 2021, Congress set aside $42.45 billion to fund BEAD, whose goal was to help close the broadband gap.

But Ferrechio’s article summarized what has been slowly bubbling up: that the rollout of the program has been mired in administrative wranglings. As she wrote,

Residents in rural America are eager to access high-speed internet under a $42.5 billion federal modernization program, but not a single home or business has been connected to new broadband networks nearly three years after President Biden signed the funding into law, and no project will break ground until sometime next year.

Lawmakers and internet companies blame the slow rollout on burdensome requirements for obtaining the funds, including climate change mandates, preferences for hiring union workers and the requirement that eligible companies prioritize the employment of “justice-impacted” people with criminal records to install broadband equipment.

The Commerce Department, which is distributing the funds under the Broadband Equity Access and Deployment (BEAD) program, is also attempting to regulate consumer rates, lawmakers say. This puts them at odds with internet providers and congressional Republicans, who say the law prohibits such regulation.

The article covers a lot, and while much of its criticism is warranted, there is a much bigger context here that needs to be explained.

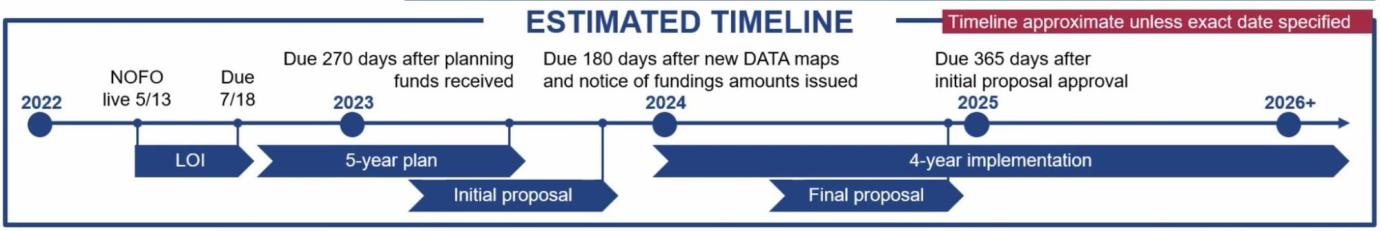

Back in the first half of 2022, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA)—the agency within the Department of Commerce administering BEAD—began reaching out to organizations to tell them about the program and what it could offer. Most of its presentations, like this one given to the Illinois Association of County Board Members, included an estimated timeline which put the implementation phase in 2026 and beyond.

The NTIA always assumed BEAD would take six years to implement. That in itself should be a scandal (six years to produce a Covid investment!).

The deeper story, however, is that a 2017 white paper essentially determined the shape of BEAD. In a way, the story is indicative of the haphazard way in which laws get adopted and then amended through the administrative process.

Broadband buildout and BEAD.

The remote nature of rural America makes it difficult for traditional internet service providers (ISPs) to reach certain communities. For simplicity’s sake, we can think of broadband deployment as mapping onto the two common financial expenditures: cap-ex and op-ex. A network must first be built and only then can service start. So the expenses on the front end are capital expenditures (cap-ex). Networks in the operation stage will need to maintain their networks through operational expenditures (op-ex). Thus, for a broadband system to be economically viable, subscriber revenues have to cover both costs.

What is unique about broadband service is that cap-ex and op-ex can vary greatly depending on a bunch of factors (such as the network technology, the infrastructure already in the area, the terrain, the footprint of the network, and the regulatory regime, among others). Costs shape service, and costs can balloon quickly. When Google Fiber was deployed in Kansas City back in 2013, it cost roughly $1,000 to get each home connected. In contrast, a project to modernize a rural Wisconsin telephone system with enhanced broadband in 2017 cost nearly $8,000 per household. The hardest-to-reach homes can often cost upward of $100,000 to connect. On top of this, these regions often cannot support internet service even if the initial costs are completely defrayed because subscriber revenues don’t cover operation costs.

BEAD was meant to solve this problem once and for all by funding projects (again, to the tune of $42.45 billion), but it was executed in exactly the opposite way it should have been.

Congress set aside a big pot of money, based on an estimate that was generated in 2014 for a 2017 white paper. Then it tasked the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to produce updated maps where the service was lacking and assigned the NTIA the role of program administrator. In other words, Congress allocated funds to close the broadband gap, even though the size and extent of that gap was a mystery.

While there are a lot of great people working at NTIA, I was never a big fan of this division of labor. Because NTIA is under the Department of Commerce, it was sure to produce a program with all of the problems that Ferrechio laid out in her Washington Times piece. Instead, Congress could have put the FCC in charge of BEAD, which would have partially insulated the program since the FCC is an independent agency outside of the executive branch. The FCC also has a long history of administering broadband deployment projects through the Universal Service Administrative Company, which would have served them well in oversight of BEAD. Still, it is likely that the FCC would also push “buy American” provisions, labor reporting requirements, and a preference for fiber.

Putting BEAD under the FCC would have also meant a different funding structure. The way that BEAD runs now, state governments as well as the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, American Samoa, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands are considered “Eligible Entities” and may apply for funding. While I can understand the argument for states running the show, this process could have been flattened with monies going directly to projects, including to the ones proposed by Eligible Entities, instead of having Eligible Entities driving the show. It would be a better version of the Community Connect Grant Program or the Rural Utility Service, both of which were at the Department of Agriculture. But BEAD is very much the product of Covid, the political process, and that 2017 whitepaper.

In the waning days of the Obama administration, the chief of the FCC’s Office of Strategic Planning and Policy Analysis, Paul de Sa, calculated that it would take $40 billion to close the broadband infrastructure gap. It was that number that anchored negotiations when BEAD was being discussed in Congress. According to de Sa, that number was rooted in the assumption that “approximately 14% of the ~160m U.S. residential and small-and-medium business locations lack access to capable fiber-to-the-premise (FTTP) and/or cable service.” Moreover, that whitepaper assumed that, “the primary goal of federal actions with respect to digital infrastructure should be to increase and accelerate profitable, incremental, private-sector investment to achieve at least 98% nationwide deployment of future-proofed, fixed broadband networks.”

The last 2 percent of households have always been the most stubborn because subscriber revenues won’t be sufficient to pay for yearly operational costs. In the world of finance, these projects will be cash flow negative on an operational basis, meaning they lose money in their operation. In other words, de Sa had made the strong case that a federal program should be targeted to offset those locations that could be viable if the initial costs were defrayed. But the program was never meant to sustain broadband services that weren’t at least cash flow positive.

Implementing BEAD.

As expected, BEAD was reinterpreted as it passed through the NTIA funding process.

The law originally intended for the selection criteria to be technologically neutral, meaning that as long as the service reached certain technical capabilities then a service area would be considered served. But the NTIA’s official funding announcement, the Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO), is structured as to give preference to fiber-based broadband services over other technologies.

Michelle P. Connolly, who served two separate terms as chief economist for the FCC, explains the problem:

This selection criteria gives fiber priority above all other technologies despite the fact that for many rural areas this is not the ideal technology to guarantee access to all households and businesses. There are other technologies such as fixed wireless and low earth orbiting (LEO) satellites currently capable of providing high speed, low latency service. These can likely be deployed more quickly and with lower cost, especially in rural areas with difficult geographic terrain.

She continues, offering a better alternative:

In evaluating project proposals, states should instead target the performance of a broadband service, not its technology type. To improve comparability between proposals, states should predefine both geographic areas for subgrantees to bid upon, as well as, speed, latency, reliability, and build out requirements. But any technology able to meet those requirements should be considered on an equal footing and chosen based on both cost and speed of deployment.

But this isn’t all that happened with the NOFO. The NOFO also applied “buy American” provisions, detailed reporting requirements when a non-unionized workforce is used, gave preference to “justice-impacted” people, and called on every state to offer rules of their own. Doug Dawson, a longtime expert in broadband deployment and author of The POTs and PANs blog, calls this regulating by grant, since “State Broadband Offices are creating grant rules that go far beyond adhering to NTIA guidelines. They are insisting on grant rules which are intended to achieve social policies.” But there is so much more, which has been documented by the Senate Commerce Committee, the Government Accounting Office, Randy May of the Free State Foundation, and Eric Fruits and Kristian Stout of the International Center for Law and Economics, among others.

To put it simply enough, the entire stack is riddled with issues. The program’s goals are poorly defined. BEAD’s structure is likely not suitable for the problem. Power is distributed among agencies. And then there are the NOFO’s implementation problems that Ferrechio detailed in her piece.

However, all of this should be expected because it is the package you get with modern federal administration. I mean, it is not like the NTIA has ever been bashful about how long this would all take. But that timeline was always way too long.

Until we chat again,

🚀 Will

AI Roundup

- A large-scale survey experiment reveals that, while large language models (LLMs) can generate persuasive political messages, their effectiveness plateaus beyond a certain model size. The study suggests that further increasing model size is unlikely to significantly enhance the persuasiveness of static LLM-generated messages.

- A machine learning model successfully identified Parkinson’s disease in 79 percent of cases up to seven years before clinical onset.

- A draft paper explores “algorithm aversion”—the idea that people prefer human judgment over algorithmic decision-making, despite evidence that algorithms often outperform humans in accuracy—while also taking a look at its counterpart, “algorithm appreciation.”

- Sens. Todd Young and Brian Schatz introduced bipartisan legislation aimed at educating the public about AI’s risks and benefits. The bill tasks the Commerce Department with launching a campaign that includes guidelines for identifying AI-generated deepfakes based on recommendations from Sen. Chuck Schumer’s AI working group.

- OpenAI gives the government early access to new AI models while simultaneously advocating for increased regulation of AI systems.

- Researchers at UC Santa Cruz found a way to eliminate matrix multiplication, the most computationally intensive aspect of running large language models. They were able to run a billion-parameter language model using only 13 watts of power (about what it takes to power a light bulb).

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.