Good afternoon. During weeks like these, with the heat index hovering in triple-digit territory, we remember that our nation’s capital was built atop an actual swamp.

Senate Democrats Pass Sweeping Climate, Drug Pricing, Taxation Package

An unpopular first-term president whose party narrowly controls the Senate found that the fate of a large part of his legislative agenda rested in the hands of the senior senator from Arizona.

For close watchers of congressional politics, the procedural parallels between last week’s Senate drama and July 2017 were hard not to notice. But unlike Republicans’ ill-fated attempt at Obamacare repeal under former President Donald Trump—which was given the decisive thumbs-down by the late Sen. John McCain after two other Republican senators, Susan Collins of Maine and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, had also voted no—Democrats’ latest reconciliation package, dubbed the Inflation Reduction Act, is on its way to becoming law. The bill passed the upper chamber on a party-line vote Sunday afternoon following a last-minute amendment to its tax provisions at the behest of Arizona Sen. Kyrsten Sinema.

The House will return to Washington, D.C., on Friday to vote on the measure.

Whether and to what extent the bill will actually reduce inflation as the title claims is disputed, but the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimates it will reduce the budget deficit over a 10-year period. The bill will also enable Medicare to negotiate the prices of certain prescription drugs and make unprecedented investments in clean energy—accomplishing longtime Democratic priorities ahead of the midterms, when the party is expected to lose control of at least one chamber of Congress.

The budget reconciliation process Democrats used to circumvent the Senate’s 60-vote threshold for passing most bills allows senators to offer unlimited amendments to the bill, leading to a “vote-a-rama” that stretched from late Saturday night through Sunday afternoon. Most amendments—whether from Sen. Bernie Sanders on the left or Republicans on the right—were really fodder for campaign messaging rather than actual substantive edits to the bill text.

But Sinema threw a wrench in her party’s plans when she signaled support for Republican Sen. John Thune’s amendment exempting subsidiaries of billion-dollar private equity firms from a new 15 percent minimum corporate tax. Republicans raised concerns the tax could be used to target small businesses. To replace the lost revenue, Thune proposed extending a cap on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction—an unacceptable idea for Democrats from high-tax states like New York and New Jersey.

Ultimately, Sinema and six other Democratic senators joined Republicans to support Thune’s amendment, before uniting with the Democratic caucus minutes later to support an amendment from Sen. Mark Warner that overrode Thune’s amendment, replacing its funding mechanism with limits on pass-through business losses that can reduce overall taxable income.

Sinema also negotiated changes to the legislation to protect advanced manufacturing from sharing an undue burden of the new 15 percent minimum corporate tax. As we wrote to you last week, analyses of the first version of the deal found that the tax hikes would disproportionately impact manufacturers. Republicans slammed it, pointing to existing supply chain woes and arguing it would undermine recently passed legislation intended to encourage manufacturers to expand operations in the United States. Sinema’s changes addressed some of the GOP’s concerns.

“With this change, capital intensive corporations, like manufacturers, will be able to use accelerated depreciation when calculating their minimum tax liability,” said Kyle Pomerleau, a tax policy expert at the conservative American Enterprise Institute. “This reduces the likelihood they are subject to the minimum tax when making large investments.”

Sinema’s changes to the Manchin-Schumer framework also included a 1 percent excise tax on stock buybacks, a practice Democrats have been broadly critical of for years.

Perhaps the most controversial tax provision in the bill: an infusion of nearly $80 billion for the Internal Revenue Service to boost enforcement of the tax code, among other priorities. The nonpartisan Congressional Research Service has a helpful breakdown of those provisions here. The money will go toward hiring tens of thousands of new IRS agents, paying rent and expenses at IRS facilities, and technologies for the agency’s operations.

We will be covering the bill’s provisions in greater detail over the coming days—starting today with an overview of the two major changes it would make to American healthcare policy.

Changes to Medicare Target Prescription Drug Costs

The first change—the extension of Affordable Care Act subsidies—is relatively simple. The ACA as first passed included subsidies to help individuals with incomes below 400 percent of the federal poverty level purchase insurance. The American Rescue Plan Act passed by Democrats in March 2021 expanded those subsidies to more people and made them more generous. The Inflation Reduction Act extends those expansions through 2025.

James Capretta, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and Robert Orr, a policy analyst at the Niskanen Center, both told The Dispatch that even if Republicans hold the purse strings in 2025, they’ll be under considerable political pressure to keep the expanded subsidies, which disproportionately benefit people in the red states that have not expanded Medicaid under the ACA.

While the expanded subsidies represent a continuation of the status quo, the second major change—Medicare drug price negotiation—is more fundamental.

According to Democratic pollster David Shor, allowing Medicare to negotiate the prices of prescription drugs is one of Democrats’ most popular policy ideas. But what will it mean in practice?

The bill directs the secretary of Health and Human Services to establish a program to “negotiate and, if applicable, renegotiate maximum fair prices for … selected drugs” with the manufacturers of those drugs. It also introduces an inflation rebate that would require pharmaceutical companies to pay insurers back for price changes exceeding inflation.

“In truth, it’s really more like a price-setting system,” Capretta said. Prices are unlikely to exceed the “maximum fair price,” defined as a certain percentage of the non-federal average manufacturer price (AMP). If a company doesn’t comply with the price negotiation for a particular drug, the sales of that drug would face a hefty excise tax, starting at 65 percent and rising to 95 percent after six months.

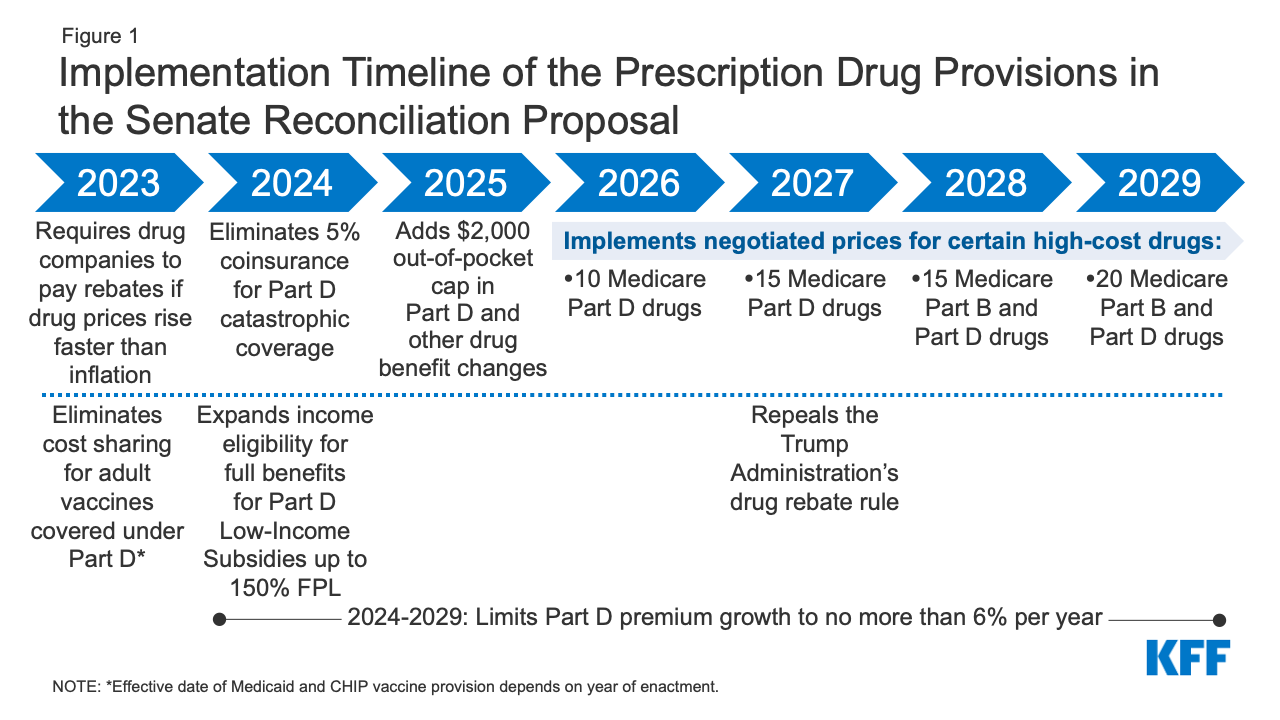

The price-setting program will start out small, limited to the most expensive drugs. Just 10 drugs from Medicare Part D, which covers retail prescription drugs, would be subject to negotiated prices in 2026. By 2029, a total of 20 drugs from Part D and Part B—which covers drugs administered in clinical settings—would be part of the program, as shown in the Kaiser Family Foundation graphic below:

“The price the government pays will go down, and the price you get charged [as a Medicare beneficiary] will go down, too.”

The legislation also caps annual Medicare Part D out-of-pocket costs at $2,000 per year.

“The beneficiaries are going to like it,” Capretta said.

Capretta’s AEI colleagues Scott Gottlieb and Benedic Ippolito predicted last week that “policymakers will seek to expand this authority once created. This would not only reflect political goals of some lawmakers, but the fact that expansions to more drugs (or earlier in their lifecycles) can serve as a ‘pay-for’ to offset future legislative spending.”

There are still some open questions about how the program will be implemented.

“It’s quite a different way of negotiating prices than what we see internationally,” Orr said. Most other developed countries use a “formulary” system: The government researches the potential benefits of a drug and decides what price it is willing to pay. Then, if its offer is rebuffed by the pharmaceutical company in question, the government simply doesn’t pay for the drug.

In some ways, the proposed American approach is simpler, since it relies on the market rather than on government expertise to decide how drugs should be priced. But it doesn’t send quite as strong a signal to the pharmaceutical industry to focus on the highest-value drugs—leaving open the opportunity for companies to “make a ton of money” on a drug “that’s ineffective but is in a disease category where people are very hungry for some sort of cure,” Orr said. (The controversial Alzheimer’s drug Aduhelm comes to mind.)

The drug pricing part of the Inflation Reduction Act would bring with it a set of other tradeoffs, Gottlieb and Ippolito noted in their article. For example, the bill could reduce incentives for the entry of generic drugs into the market, “entrench problematic rebating practices,” and hamper certain forms of research and innovation.

“These tradeoffs are important to weigh against the benefits that stem from lower costs,” they wrote.

Sunday’s votes showed that Senate Democrats are unanimous in their judgment: Measurably lower costs are worth the risk of these more ambiguous potential downsides.

“There is a reason why Big Pharma is fighting this so hard,” Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden told reporters late Saturday night. “They know once you put negotiation into law—embedded into law—there will be no turning back.”

“This is a seismic shift between government and this lobby,” Wyden said.

On the Floor

The Senate is out. The House will return Friday to debate and vote on the Senate-passed climate and drug pricing legislation.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.