Good morning. Congress is out, and I’m on the prowl for good story ideas. Send thoughts/tips/interesting bills my way! I’m at haley@thedispatch.com.

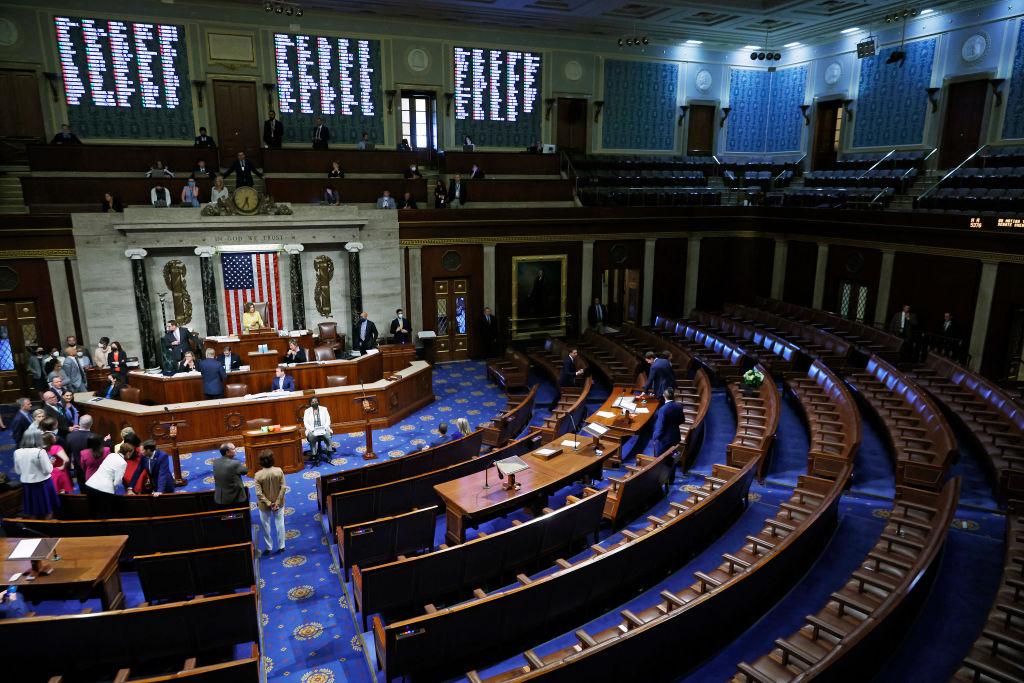

Proxy Voting Persists

Traditionally, the annual August recess is an opportunity for members of Congress to spend some quality time away from the Capitol and in their districts.

But in the era of proxy voting, August recess isn’t tied to the calendar. For some lawmakers, it’s a state of mind.

Using emergency procedures created in response to the coronavirus pandemic, some representatives have scarcely visited the Capitol this year. Of these, a few have legitimate health problems, but others are running for different offices, plan to retire at the end of the 117th Congress, or simply don’t want to travel a long way to be at the Capitol in person.

We’ve previously reported on a few high-profile cases, including members who were relying on proxy voting to hold campaign events in their home states. You may remember our April story about Democratic Rep. Charlie Crist’s use of proxy voting—since then, he has largely remained on the campaign trail in Florida, where he is running for governor.

The Dispatch’s updated review of data from the House Clerk’s Office found that Crist has voted in person only twelve days this year. That’s out of 69 days the House was in and holding roll call votes so far in 2022. Crist voted in person four days in March, seven days in May, and one day in July. He has cast the rest of his votes remotely. (Crist’s office did not respond to The Dispatch’s request for comment.)

Lawmakers pursuing other offices are typically more absent from the Capitol in election years, but proxy voting has enabled members to focus on their campaigns at home and still weigh in on legislation.

That wasn’t what the system was created for. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi established proxy voting at the outset of the coronavirus pandemic to prevent the spread of the virus.

Members still submit form letters today claiming the pandemic as the reason they cannot travel or perform their duties in person (regardless of the real reasons behind their absences). As the November midterm elections approach, many House members from both parties are blatantly using proxy voting out of convenience.

Most recently, about a third of the House voted remotely on Democrats’ sweeping $700 billion reconciliation package. When the House convened to vote on the climate change response and drug pricing bill earlier this month, 158 members used proxy voting instead of showing up in person.

August recess had already begun when leaders brought the bill forward, and members were at home in their districts. Some openly acknowledged the real reason they voted remotely: They just didn’t want to rearrange their schedules.

“I have to cancel 15 events for one vote?” Nebraska GOP Rep. Don Bacon, who voted by proxy on the bill, told Axios. “I’m just in a mode where you can’t just move the schedule around.”

The same week, Pelosi announced she would be extending the ability to vote remotely through late September.

The coming months could represent a last hurrah for the practice, which Republican leaders have pledged to scrap if they retake the chamber this year. They argue that physically being at the Capitol is key to collaborating on legislation. Members who work remotely are also precluded from attending sensitive briefings from administration officials on a range of important issues.

Many lawmakers have had valid reasons for voting by proxy over the past two years beyond the immediate concerns of the coronavirus pandemic—sick family members, terminal illnesses, surgeries, and taking care of new babies, for example. But members have also used the system for some frivolous reasons without consequences from the start, like attending space launches and going to political fundraisers.

The flaws in proxy voting have become more clear this year, as effective vaccines are widely available and as American institutions have largely returned to in-person work.

“At the start, it was the least bad option available to the House in terms of how to deal with needing to offer members and staff protections from COVID,” said Molly Reynolds, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “It still, I think, has a role to play in that. Members continue to contract COVID.”

But at the same time, she said, “We have seen members use it for reasons that are really not at all what it was originally intended to do.”

Reynolds told The Dispatch she is concerned that if proxy voting continues to be an option without much oversight or guardrails, it could hurt the institution and undermine legislative work that is best done in person.

“If we sort of keep it as a little bit of a free-for-all, which is where it is now, I do think we also start to create the possibility that members might use proxy voting as part of an overall image that says, ‘I don’t have to go to Washington. I don’t want to be a creature of the swamp. I can do my job without having to go and be around all those icky lobbyists,’ and that sort of thing,” Reynolds said.

“I don’t think we’ve seen this quite yet, but it is a concern that I have had as we navigate this procedure, that I could imagine happening if it stuck around in an unfettered way in the future.”

The Climate Provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act

Last week, my colleague Price wrote to you about the health care and tax aspects of the Democratic reconciliation bill. On the site today, he has a follow-up piece examining some of the bill’s climate components—and where they could fall short.

“The legislation will spend $369 billion over the next decade on a portfolio of energy and climate issues, primarily in the form of new and expanded tax credits for both manufacturers and consumers—the largest federal climate investment ever,” Price writes.

He looks into one of the more controversial parts of the climate plan: limiting electric vehicle tax credits to purchases of vehicles with a certain amount of battery components and minerals sourced from North America. It’s intended to encourage auto manufacturers to move their supply chains to the United States, or at least nearby, instead of relying on Chinese suppliers that can hold a significant risk of being involved in forced labor. From Price’s story:

At the insistence of Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin, the full value of the credit is limited to EVs with a certain percentage of battery components and critical minerals made and sourced in North America. Decreasing reliance on Chinese supply chains is a laudable goal. But it means fewer EV purchases will qualify for the credit. According to the Alliance for Automotive Innovation, 70 percent of EVs are now ineligible for the credit due to the bill’s passage, “and none would qualify for the full credit when additional sourcing requirements go into effect” next year. Congressional Budget Office estimates suggest that “a total of just 237,000 EVs will qualify” in the first five years of the credit. For comparison, General Motors “expects to sell 400,000 EVs by the end of 2023,” according to Reuters.

“The timeline is perhaps overly aggressive in terms of balancing supply chain concerns against the concerns of, we just need to get more EVs out on the road,” said Kristin Eberhard, director of climate policy at the Niskanen Center.

Read the whole piece here.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.