China and India have quarreled over their border for nearly six decades. But Monday was the deadliest day in their dispute since 1975. At least 20 Indian soldiers were killed when a skirmish broke out in the Galwan river valley in the remote Ladakh region of the Himalayas. Tensions had been mounting for weeks, with President Trump offering to mediate the dispute in late May. (Neither side took him up on the offer.)

The Indian government previously warned that the People’s Republic of China (PRC), ruled by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), has sent thousands of troops into the area since the beginning of the year. Naturally, the CCP accuses India of being the provocateur. Earlier Wednesday, China’s foreign ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian claimed that Indian troops first “provoked and attacked Chinese personnel.”

From this great distance, we cannot know for certain what transpired. It isn’t even clear how the Indian soldiers were killed, or how many casualties the Chinese suffered. Both sides contend that not a single shot was fired. This is in keeping with their decades-old agreement to avoid using arms. In what must have been a bizarre spectacle, their men supposedly resorted to fisticuffs and throwing rocks.

We do know that the CCP has been aggressively asserting its territorial claims throughout the coronavirus pandemic, taking advantage of a distracted world. And the CCP’s incursion into the Galwan river valley is entirely consistent with this pattern of behavior both at sea and on land. On April 3, a Chinese coast guard vessel sank a Vietnamese fishing boat near the Paracel Islands in the South China Sea. In May, the Chinese harassed Japanese vessels in the East China Sea. And late last month the CCP enacted a new national security law for Hong Kong, threatening to end the region’s longstanding autonomy. These moves occurred in conjunction with the CCP’s increasingly hostile stance toward Taiwan and America’s naval presence.

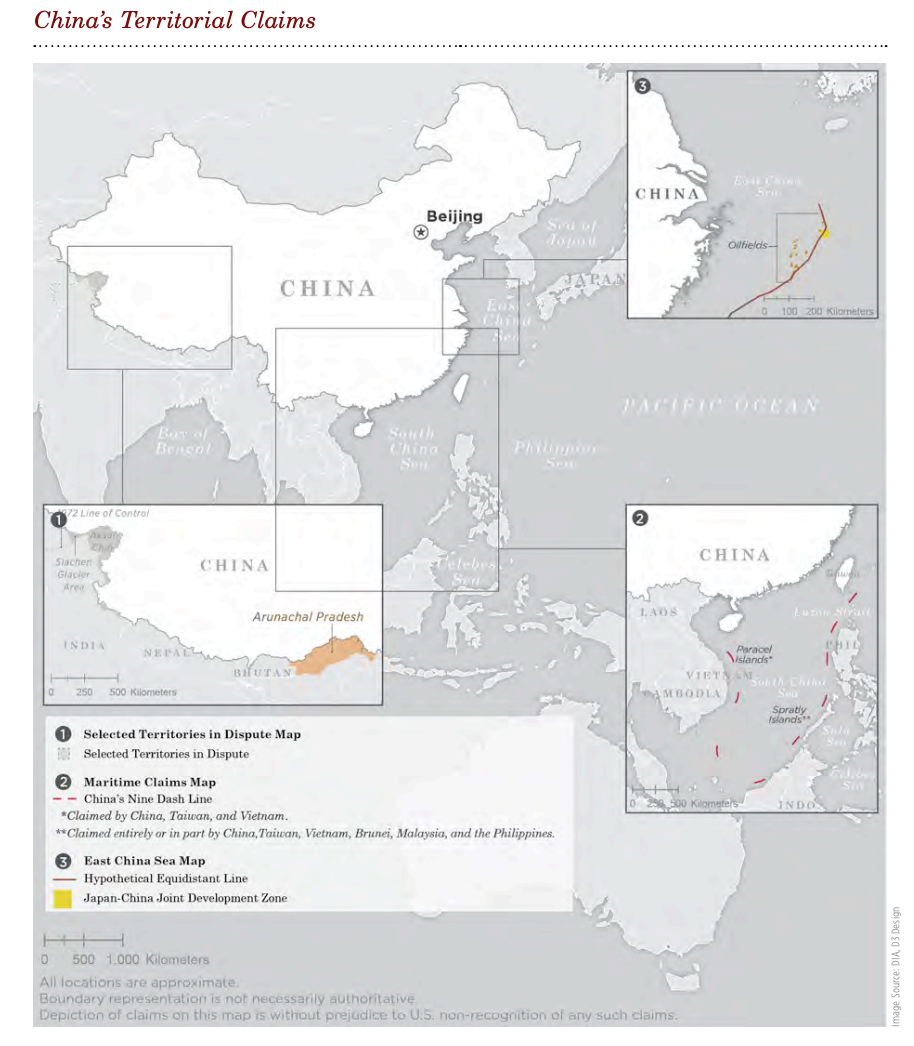

In this context, it is entirely unsurprising to see the CCP asserting its longstanding claims in the disputed Ladakh region. The site of the clash is depicted on maps produced by the New York Times and BBC News. In addition, a map created by the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) is reproduced below. That map depicts the border dispute between China and India alongside the CCP’s other territorial and maritime claims.

Although both countries say they are working to resolve the matter diplomatically, it is likely that we will hear about this unresolved matter again. And while the death toll in the most recent clash is alarming, it isn’t altogether surprising. The issue has been boiling for years.

China and India dispute multiple locations along their border.

China and India share more than 2,100 miles of border and multiple locations along it are contested. The dispute has roots in the end of British colonialism, the 1947 partition of India, and the various conflicts that followed in the 20th century.

In 1962, China and India fought a war when the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) of China launched an invasion. The fighting took place in Ladakh, the same general area where the clashes occurred this week. The war was also fought in a region now known as Arunachal Pradesh, which lies considerably to the west. That short-lived conflict resulted in a Chinese victory and a ceasefire, but the competing claims were never entirely settled. India continued to rule over Arunachal Pradesh, but the Chinese government maintains it is rightfully part of Tibet, which the area borders. After 1962, the Chinese controlled Aksai Chin, an area connected to Ladakh that straddles the regions of Xinjiang and Tibet. Beijing accuses “separatists” in both regions of attempting to break away from the motherland. Aksai Chin connects Xinjiang and Tibet, making it strategically valuable to the CCP. Pakistan technically ceded control of Aksai Chin to China in 1964, but India doesn’t recognize that move and hasn’t given up on its own claim.

You can see the two main areas at the heart of the dispute on the map below. The map was included in the DIA’s 2019 report on China’s military power. That report is one of several produced by the DIA on foreign militaries each year. The cut-out toward the bottom left depicts the extensive border between India and China, which is interrupted by Nepal and the tiny landlocked kingdom of Bhutan. The Galwan river valley, the site of the fighting this week, is in the small area of Ladakh that is shaded dark gray, while Arunachal Pradesh is a great distance away, to the east of Bhutan.

As a result of the 1962 war, the two countries established a de facto Line of Actual Control (LAC), which was intended to demarcate the border between the two countries. The LAC has been problematic. It cuts across uneven terrain covering a large land expanse filled with waterways and other natural impediments. Further complicating matters is the fact that Pakistan disputes India’s territorial claims in Kashmir. A separate line of control demarcates those two countries’ forces.

Until this week, India and China rarely resorted to violence along the LAC. In 1975, four Indian soldiers on patrol were killed in a Chinese ambush. This appears to be the last time that Indian casualties were incurred during the border flare-ups. That incident occurred in Arunachal Pradesh (previously known as the Northeast Frontier Agency), which is not where the fighting occurred this week.

Despite the somewhat amorphous nature of the LAC, China and India made it a formal part of an accord in 1993. That agreement was dedicated to maintaining “Peace and Tranquility along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas” and it established protocols for mitigating the threat of violence resulting from disputes over the LAC. “In case personnel of one side cross the line of actual control, upon being cautioned by the other side, they shall immediately pull back to their own side of the line of actual control,” the agreement reads. The two countries have adhered to that clause in the past, but obviously not this week. They fleshed out subsequent agreements dealing with the LAC in 1996, 2005, 2012 and 2013. The 2013 accord called for cooperation to combat illicit smuggling networks and other criminal activity, while also stating the two sides would work together to mitigate the effects of natural disasters. That agreement allowed for joint military exercises, while forbidding each side from harassing the other in areas where the LAC boundary is murky.

More often than not, the two countries have adhered to the 2013 accord. But there have been noteworthy exceptions.

In September 2016, for instance, more than 40 Chinese troops temporarily set up camp within Indian-controlled Arunachal Pradesh. Indian forces noticed the incursion, which stretched nearly 30 miles onto the Indian side, and demanded the Chinese leave. The situation was diffused only after the two sides held a flag-officer meeting on the Chinese side of the border. Other meetings would follow. And the two countries conducted joint counterterrorism exercises and military exercises, including in the border region of Ladakh, in the months that followed.

But that wasn’t the end of the story. Chinese forces have been probing multiple areas along the border with India, including in disputed territory administered by Bhutan. In June 2017, India intervened to block a Chinese construction crew that was attempting to extend a road through the Doka La Pass, a tri-border area sandwiched near the Himalayan border. The two sides locked horns, without resorting to violence, in a 70-day standoff. They agreed to withdraw forces from the area, but they’ve been surveilling each other ever since. In December 2017, an Indian drone crashed near the standoff site, with the Chinese accusing India of violating its territorial sovereignty.

That incident was the most significant flashpoint until this year, when the Chinese decided to press their claims in Ladakh once again.

China is increasingly aggressive toward its neighbors.

The clash between Chinese and Indian forces in the Galwan river valley will only exacerbate concerns regarding the CCP’s intentions. China has long sought to extend its borders, but as noted above, its recent actions across multiple theaters are especially alarming. The DIA’s director, Lt. Gen. Robert P. Ashley Jr., warned about this dynamic in the introduction to his agency’s 2019 report on China’s military power. China has “fought border skirmishes with the Soviet Union, India, and a unified Vietnam” in the past, Ashley noted. “In all three cases, military action was an integral part of Chinese diplomatic negotiations.” The CCP has been willing to use diplomacy to settle these claims on multiple occasions, but “remains in contention with Japan, the Philippines, Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam over maritime borders, which may in part explain motivation for the PLA Navy’s impressive growth and the new emphasis on maritime law enforcement capabilities.”

Fueling America’s concerns about the CCP’s desire for territorial aggrandizement is its ever-expanding defense budget. The DIA’s reports show that China’s official military budget for 2016 and 2017 totaled approximately $300 billion. This was greater than the combined total spent by India, Japan, the Republic of Korea, and Taiwan. Those four countries spent about $272 billion on their militaries during those same two years. A similar comparison wasn’t included in the DIA’s report for 2019, but this imbalance of power almost certainly remains in effect today. China’s official military budget increased from $156.9 billion in 2017 to $170.4 billion in 2018 (the most recent years documented in the DIA’s annual assessments), according to the DIA’s 2019 report.

And these ballpark figures likely undercount China’s military spending. These are just the official figures provided by Beijing, which doesn’t exactly have a stellar record of transparency. The CCP pursues a “military-civil fusion strategy,” which blurs the line between direct military spending and expenditures on civilian endeavors. And the CCP has enjoyed what the DIA describes as a “latecomer advantage,” meaning China “has not had to invest in costly R&D of new technologies to the same degree as the United States.” Instead, the CCP “has routinely adopted the best and most effective platforms found in foreign militaries through direct purchase, retrofits, or theft of intellectual property.” This means China gets more for less.

For all of these reasons, China’s official military budget is a lowball figure. Even so, Beijing’s official figures indicate a stunning growth in total military expenditures over time—a “threefold increase since 2002,” according to the DIA.

And as recent events show, the CCP is spending at least some of that money so that it can intimidate and threaten its neighbors.

Photograph by Faisal Khan/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.