New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day together constitute a very strange holiday: Mardi Gras, Lent, and Easter all crammed into one stretch of about 12 hours, from around 8 p.m. on December 31 to around 8 a.m. on January 1, depending on how hard you like to party, with the Lenten part extending as long as your resolutions do.

Whereas Thanksgiving is a Christian holiday disguised as a secular one, New Year’s remains true to its pagan roots—alongside Halloween, which has turned into something of a heathen cultural juggernaut, it is our most obviously pagan festival. We owe the date itself to Julius Caesar’s calendar reforms, which moved the date of the new year from the Ides of March to January 1 and the patron of the celebration from the war god Mars to the two-faced Janus, the much more ancient personification of beginnings and endings. Knowing the calendar adds a little richness to the story of Caesar’s assassination on the Ides of March, the most political day of the Roman year, the day on which new consuls began their terms, with the Romans counting their years from one consulship to the next in roughly the same way later Europeans counted their years from the coronations of their kings. Assassinating Caesar on the Ides of March was profoundly conservative in its symbolism: Caesar’s tyranny was of a piece with his contempt for Roman mores and tradition.

(Mores? O, mores! As Cicero observed about another would-be tyrant in the lines immediately following that famous exclamation: “The senate knows very well what is going on, and the consul sees, too, yet that man continues to live among us. He even comes to the senate and participates in public affairs, marking each one of us with his eyes for future retaliation. But we men of fortitude seem to believe that we do enough for the republic if we just avoid his attacks and escape his fury.” Nothing to see here, reader!)

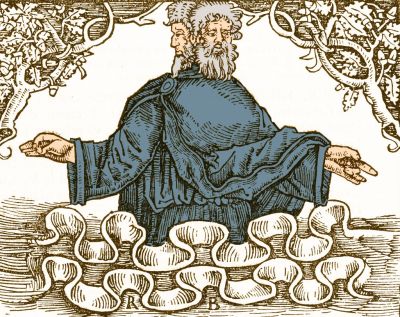

Janus, who lends his name to the first month, is not one of those fancy Greek gods repurposed by the Romans. Janus is an old local, probably borrowed by the Romans from the Etruscans, an adaptation of their two-faced god, Culsans. And while there is much about the classical Greco-Roman world that is very strange to us—Zeus and Athena and all those characters—that which lies on the far side of it in history is positively alien: the old weirdness.

Janus is not the only two-faced entity from the era: You can also see Castor and Pollux depicted in a similar way, distinguishable from Janus by their lack of beards. Castor and Pollux are twins (but only half-brothers, and there is your invitation to read about “heteropaternal superfecundation”), and it is easy to see how twins and Janus would come to be linked. There is something uncanny about twins (or triplets!), just as there is something ambiguous about doorways, which were Janus’ special domain: He was depicted above them or beside them, and his name is derived from the same root word. (“Claude ianuam” is how you tell someone “close the door” in Latin.) Beginnings that are also endings, doorways, points of departure, liminal spaces: These have always been magical locations. It is not for nothing that Robert Johnson goes down to the crossroads to sell his soul. You might meet Old Nick down at the crossroads, but you might very well meet Janus, or his distant relation Hecate (three-bodied where Janus is two-faced), or Hermes (known by the epithet “doorkeeper”), or Odin (who is the Germanic answer to Hermes), or another ancient deity who was honored at such places.

New Year’s is the crossroads on the calendar. Which way will you go?

That is the point of making resolutions at the moment of transition: You can resolve to stop drinking or get in shape or stop spending so much money on any day of the year you like—and the churches are always open for those who feel the need for a special place to make a vow—but there is a very old and generally unspoken belief that resolving to take a new course in life has a special meaning when it happens at New Year’s or on a birthday or on some other similar occasion. I once worked for a newspaper publisher who kept a full-time astrologer on staff, not to write horoscopes but to advise the boss on business matters, with the result being that we could only launch major projects on dates with certain numbers in them. (I think these were 5, 14, and 23, but I may be mistaken.) Most cultures have a magical idea of auspicious times or occasions for certain undertakings, and it apparently is going to take more than two millennia of Christianity to snuff out such superstition—indeed, as with so much else in the Christian conquest of the pagan world, the old ways were simply incorporated into the new faith, with kings and conquerors beginning ambitious projects on Pentecost or on the feast day of the national saint. (More twins? Henry V was happy to fight his most famous battle on the feast days of Sts. Crispin and Crispinian, twins and martyrs. The day proved less auspicious for the English centuries later at the Battle of Balaclava and those two great sartorial innovators, Baron Raglan and Lord Cardigan.) We seem to need something to structure our thinking when it comes to these matters, and, once the structures have been in place long enough, they become magical totems, religious observances, or civic holidays.

I mentioned Halloween above as a pagan holiday on the rise. It is not difficult to understand its popularity: If the baby boomers and Generation X both followed the predictable path of turning toward social conservatism (in practice if not necessarily in politics) after aging out of the Dionysian ecstasies, the hard-used millennials and their heirs turned to hysterical moral puritanism and ruthlessly enforced conformity without ever really doing the fun stuff first, producing a generation of people who are afraid of everything: strangers, shop clerks, sex, telephone calls, being apart from their parents, etc. Putting on a mask and ingesting intoxicants, particularly around the time of autumn fertility rites, is an ancient means of encouraging the propagation of the species. But, in spite of the COVID-era uptick in alcohol consumption, booze seems to have been going out of fashion for the smart set for years now—but not on Halloween. Young people are less inclined than their elders to binge drink on New Year’s Eve, which is, in my view, a good thing: New Year’s Eve is the most tedious kind of self-conscious bacchanalia, and there is nothing sadder than the sight of hundreds or thousands of people desperately trying to convince themselves that they are having a good time.

There is a reason Janus has two faces. New Year’s is a reminder that the ecstatic experience and the drive toward self-improvement and social reform often go hand-in-hand: As Harold Bloom notes in The American Religion, that famous revival meeting at Cane Ridge, Kentucky, in 1801, part of the Second Great Awakening, was a little bit of a hootenanny:

The drunk, sexually aroused communicants at Cane Ridge, like their drugged and aroused Woodstockian descendants a century and a half later, participated in a kind of orgiastic individualism, in which all the holy rolling was the outward mark of an inward grace that traumatically put away frontier loneliness and instead put on the doctrine of experience that exalted such loneliness into being-alone-with-Jesus.

By the time of Woodstock, Americans were back to a more frank form of youth worship, and so those communicants only needed to be alone with themselves—the thing that now terrifies young people most. The United States is a religion factory—Mormonism, Methodism, Christian Science, Pentecostalism, Seventh-Day Adventism, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and many others, all born from the same soil and many born within a few years and a few miles of one another—but Bloom would argue that what we’ve really done is continue reinventing the same religion with the same object of worship: ourselves.

But, you know, nothing new under the sun and all that.

Janus has the advantage of being able to look at these things from more than one point of view. “Two-faced” is another way of saying “duplicitous” or “hypocritical,” but an extra set of eyes is sometimes just the thing that is needed to take in the whole scene. Let him who has eyes—or lots of them—see. The other two-faced icon looking over our shoulders is from the theater (which is only what remains of the oldest temples), the paired masks of tragedy and comedy. To look at the facts of the human case—the tragic, comic facts of the case—from more than one angle does not make one godlike: It makes one more human and, maybe, more inclined to cut one’s fellow scoundrels some slack. As New Year’s resolutions go, that isn’t the worst one.

Of course, change is possible, both for individuals (my own life today is radically different from what it was only a few years ago, though this has relatively little to do with any resolve of which I can boast) and for peoples. As a matter of geometry, one crossroads is very much like another, and whether any particular turn is the right one or the wrong one may be impossible to know until one has gone some ways down the road. (With apologies to Bugs Bunny, any turn at Albuquerque will do—just stand on the gas and get out of there.) As old gods go, Janus was a good fit for the Romans, but not for us Americans—we don’t know what to do with a two-faced god, having, as we do, a profound national disinclination for looking backward. We are an ahistorical people who think this all just fell out of the sky, blessed and cursed to wake up every morning in a new world where every day is New Year’s Day.

Somewhere, Janus is no doubt laughing with both mouths.

In Other News …

“Sore muscles are the new hangover,” says the advertisement for … something … in my local gym. But, taking into the account the possibility that some of you will have shorter attention spans this morning, I’ll try to keep the rest brief.

Economics for English Majors

Boy, am I annoyed with NPR. I’m often annoyed with NPR, of course, which does things like publish breathless reports about the new criminal prevalence of “exploding bullets” that do not actually exist. (I’ve been on them to retract that fake report for years. No progress.) In fact, I used to be on NPR pretty often, but NPR does not tolerate criticism very well—I am sure that many other conservatives who have been in the token-conservative slot on various left-leaning outlets have had the same experience.

But beyond the normal annoying NPR stuff, this report on generic pharmaceuticals was just astoundingly dumb and irritating. A great problem with the U.S. pharmaceutical industry, according to NPR pharmaceutical correspondent Sydney Lupkin, is that generic drugs do not cost enough. Really—that’s the claim: We are suffering from a market failure that has produced generic drugs that are too cheap. If you think I am oversimplifying the report, please check it out for yourself. The idea is that low prices keep firms from investing in facilities to produce generic drugs and leave patients vulnerable to unexpected interruptions in supply when the sole producer of a drug goes out of business.

About that, a few thoughts:

- Lupkin confuses low consumer prices with low profit margins. Some things are relatively cheap for buyers and, at the same time, wildly profitable for sellers. A fountain soda that costs $1.99 at a convenience store is pretty cheap to buy, but it is a whole lot cheaper to make—just a few cents by some estimates—and is, therefore, very profitable to sell. At the same time, some things are very expensive to buy while producing very little profit for providers. The U.S. government spends damn near $2 trillion a year on Medicare and Medicaid, but two-thirds of hospitals lose money on serving those patients. Some luxury-goods retailers sell very expensive pieces at a relatively low margin while making up the money on high-margin/lower-price items such as designer sunglasses or T-shirts. Food at McDonald’s doesn’t cost very much—but McDonald’s makes a whole lot of money selling it. Price isn’t profit.

- Beyond that, Lupkin never bothers to ask the most obvious question: If there is only one provider of a particular drug in the marketplace—if there is, in effect, a monopoly—then why is profitability so low? Are we really expected to believe that the great problem with the prescription-drug market is that soulless pharmaceutical corporations do not know how to properly exploit a monopoly? Typically, it is competition rather than the lack of it that drives prices down. If, as Lupkin claims, the market is not competitive, then what is stopping monopoly or near-monopoly providers from raising prices?

- When a generics manufacturer goes out of business, another firm may enter the market. “But getting the factory up and running again is tricky because the water, air and mechanical systems had been shut down for so long,” Lupkin writes. Is that really what’s keeping new players out of the generics market—figuring out how to switch the A/C back on? Might there be other hurdles? For example, federal regulations seeking to enforce “maximum fair prices” on certain pharmaceuticals? Or 30 years’ worth of public policy ideas designed to interfere with normal market pricing for pharmaceuticals?

Maddening stuff. And it’s not the work of some unlettered intern—it’s the g------d pharmaceuticals correspondent.

Words About Words

If you know a little about words, then you can figure out words and phrases you don’t know, e.g., the abovementioned “heteropaternal superfecundation,” which is what you get on those very rare occasions when a woman (pardon me: an ovulating person) produces two eggs in a single menstrual cycle and each egg is fertilized by a different man (pardon me: ejaculating person), producing fraternal twins with different fathers. Presumably, this is called “heteropaternal superfecundation” because there wasn’t a Latin word for gangbang.

(The Greeks probably had a whole extensive vocabulary for that, like the apocryphal tale of the Inuit having 400 words for snow.)

This is not to be confused with a dicavitary pregnancy resulting from uterus didelphys, in which a woman who has two uteruses becomes pregnant in both of them at the same time.

Elsewhere

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can see my New York Post columns here.

Please subscribe to The Dispatch if you haven’t.

In Closing

Please spare a thought for the ongoing crime against humanity that is the Russian war against Ukraine—and for the contemptible American legislators who are doing Vladimir Putin’s bidding while pretending to be engaged in fiscal restraint, of all implausible things.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.