You get a lot of advice when you have a baby—more advice than you probably are in the market for, in fact—and it’s usually the same stuff over and over again, the sort of thing people say because they feel that they are supposed to say something but don’t have anything to say, so it is the familiar litany: Diapers! Sleep deprivation! Start saving for college! Etc.

As they say: The worst vice is advice.

What they don’t tell you about is how long that first night is going to be—not because you’re tired, but because you are terrified. Newborn babies are tiny and fragile and entirely helpless, of course, but they also are mysterious. Some babies thrive from the beginning, some have inexplicable troubles—and nobody really knows why. Terrible things happen with babies sometimes. When I was in college, one of my undergraduate friends was diagnosed with lung cancer, and the first thing people wanted to know was whether she smoked, which she didn’t, or if her parents smoked, which they didn’t—people wanted to know what she had done to deserve lung cancer. When children are sick or injured or unhappy, mothers and fathers (but mostly mothers) get the same thing: What did you do wrong? They get it from their friends and families, and they get it from themselves.

“A sword shall pierce thy own soul, also.”

Our little boy was born in Dallas, a city particularly blessed with rich medical resources. We didn’t need much of that, though we were constantly worried, of course—one of the consequences of our medical professionals’ remarkable new abilities in scanning and imaging is that tiny (literally tiny) things that could indicate a problem but don’t actually indicate a problem end up on your radar (something close to literal radar in some cases) when a generation ago they would have come and gone without anybody noticing. And the terminology is terrifying: Ventriculomegaly sounds pretty bad, but it’s usually nothing. (Usually.) You don’t want to be sick, and you really don’t want your children to be sick, but, if that is how things have to be, you want to be sick in Dallas or Houston or Phoenix or Washington.

Not everyone has it so good. Even now, and certainly in the past.

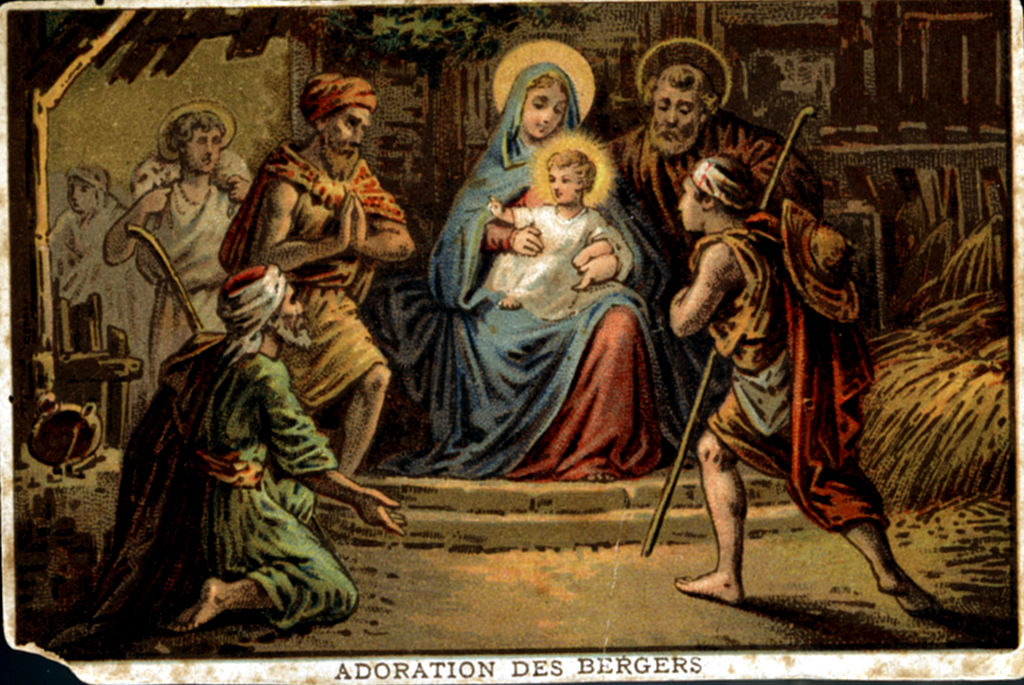

The pedants will correct you about the manger scene—He wasn’t born in a stable, whatever the songs may say, and His family wasn’t turned away from the over-peopled inns of Bethlehem, their ancestral city, where they would have been staying with relatives. The place where there was no room wasn’t at whatever passed for a hotel in first-century Palestine but in the kataluma, in the biblical Greek, meaning the guest room in a family home—it is the same word used to indicate the “upper room” where the Last Supper was eaten. “In the Christmas story, Jesus is not sad and lonely, some distance away in the manger, needing our sympathy. He is in the midst of the family, and all the visiting relations, right in the thick of it and demanding our attention,” as the Reverend Ian Paul of Fuller Theological Seminary puts it. It is good to have family nearby, but the scene is hardly any less desperate for being less lonely. There were animals feeding nearby not because Jesus was born in a barn but because that was how most people lived then—in a world lit only by fire, fearful of strangers with their strange gods made of wood and mud, no recourse against Caesar.

So, no, it wasn’t a stable—it wasn’t Cedars-Sinai or the Cleveland Clinic, either, and a far cry from the sputtering last days of Anno Domini 2022.

The anatomically modern human being has been around for about 300,000 years—which means that in terms of the human timeline, the events in Bethlehem were very, very recent. We have a tendency to think of people who lived hundreds or thousands of years ago as a species of hominid aliens—superficially like us, but essentially unlike us. That is precisely the wrong way to think about it. The family there in Bethlehem were us exactly. Yes, their cultural background was different, and they knew a little bit less about the world than we do—imagine what they would have thought of an MRI machine!—but they knew where babies come from. The religious and social significance of virginity was not something randomly chosen by them or their forebears. Theirs may have been an obscure corner of the empire, but they were under the heel of the greatest political power the world had ever known—a global trading power that was multireligious, multiethnic, and multinational. The couple were in Bethlehem engaged in the very modern business of trying to comply with an overly complex tax code, getting bullied and condescended to by imperial bureaucrats. A visitation from an angel bearing a message from God Himself was not an everyday occurrence—no more for them than for us. Everything that seems fanciful and preposterous about the story to us sounded fanciful and preposterous to them. “Oh, your betrothed is pregnant?” Knowing glances, smirks.

“And a virgin, you say?”

The first epidural was about 2,000 years in the future, as was penicillin. There was a night of pain and fear, longing, joy, relief, and probably some shame, too, given Mary’s situation—Joseph may have believed her, but there would have been others who didn’t, probably including most members of their families. Even with the stars and the signs and the angelic visitations, even with the mysterious strangers from the east and their evocative gifts—gold for a king, incense for a priest, myrrh for a dead man—even if we credit all of that as literally true, what happened next? Mother and father, tiny newborn, all of them newly entered into a world and a life that was not what it had been the day before. The supernatural side of the story is incredible—but the human side of the story is a matter of the most common experience we human beings have in common: an hour of blood and tears, the facts of life aggressively and pungently present.

And, then, the long night.

Ours is not a different world, really, but it is a much richer one, and one that is full of marvels. But what would it take to find a child being born in “such mean estate” as that of Jesus? An eight-hour flight and a two-hour drive? Maybe not even that. Before we retreat into mythology and anthropomorphize the donkeys and fool ourselves into thinking that there might have been some warmth in the light of that cold and remote star, let us remain here, for an hour or two, scrubbing up the blood and the waste, bone-tired, tending to the baby while others tend to the animals, getting pushed around by Caesar, being gossiped about by our families and friends, at times unsure of those closest to us, anxious, hands unsteady, in the long night, being human—until:

I am all at once what Christ is,

Since he was what I am, and

This Jack, joke, poor potsherd,

Patch, matchwood, immortal diamond

Is immortal diamond.

But the diamonds come later. Much later. Stable or inn or kataluma—it probably won’t do to apply too much scholarship to the popular stories and songs about Christmas, but there is a great theological truth spoken in the sentimental song about the drummer boy: “I have no gift to bring that’s fit to give a king.” Rich as we are, we have only the old kind of riches—but we have a new kind of king, there in the manger.

The night was anything but silent, of course. The baby crying every two hours, wanting to nurse or needing some other attention. The mother has a great deal to do. The father, anxious and possibly feeling superfluous, waits and watches, hoping to be of use but suspecting that he isn’t. The mother and child are, as mandated by the biological facts of the case, the central players in the first act of the drama—in Gerard van Honthors’ magnificent Adoration of the Child, Joseph is barely even visible, fading into the background just as he fades from the Biblical account, and in Caravaggio’s Nativity, it isn’t even clear that Joseph is depicted, even though St. Francis is in the picture 12 centuries ahead of his scheduled appearance on Earth. We can be sure that Joseph was doing what Mary is described as doing: He treasured these things in his heart and pondered them. “A sword shall pierce through thy own soul, also.”

It took an incarnation to show us, Homo allegedly sapiens, that man can be more than meat, that we might discover in Bethlehem the almost imperceptible shifting and struggle of a fallen world trying to get to its feet. But on that long uneasy night, the power and the glory and the kingdom were far away, years and miles away, and if there were any immortal diamonds to be had, the wise men weren’t saying much about them. Nobody at the beginning knows how the story is going to end. They only know what they know: mother and father and newborn child.

Treasure these things in your heart. Ponder them.

Economics for English Majors

Today is Boxing Day, and nobody is entirely sure why it is called that. Opinion is divided between “boxing” referring to the opening of church poor-boxes on St. Stephen’s Day (the feast Good King Wenceslas looked out on) and “boxing” referring to “Christmas boxes” given as tips to workmen and to servants—the latter were expected to be at work in their masters’ households on Christmas but were given leave to visit their families on the second day of Christmastide, with their employers giving them boxes of food and other gifts to bring on their visit.

If you want to know why some people hate tipping, think about the origin of Boxing Day. Is the gift an act of charity, as in the distribution of church alms to the poor, or is it a form of regularly expected compensation for employees? Waiters and bartenders and other people in tip-paid professions are not beggars—financially, some of them do quite well—but structuring the bulk of their compensation as gratuity puts them in a position of quietly hoping—and begging—that they will be paid appropriately. That’s part of the case against tipping, anyway. The case for tipping is that some people earn a lot more money that way: Going through an airport a few years ago, I enjoyed the pitch from a shoeshine man: “The shine is $4, but it’s not a $4 shine.” He was right, and I paid him appropriately. But if there were a minimum wage of $20 per shine and he had to advertise it, he’d probably make less money, because fewer people would sit for shoeshines.

(I have in the past suggested that what you should pay for a shoeshine is 5 percent of the cost of the shoes. If you’re walking around in $2,000 boots, hit the guy with a Benjamin if the work is good—you can afford it.)

We Americans like to think of ourselves as living in a classless society, which isn’t exactly right—but we do live in a society in which having money matters a heck of a lot more than where your grandfather went to school. The problem with tipping is that it introduces ambiguity into the commercial relationship—is this a wage or a gift?

I am curious about your thoughts. Please do share them in the comments.

Words About Words

One of the dumb things about our contemporary political discourse is that we seem to have taken to heart that most vacuous of truisms: Everything is everything. Every problem is every other problem. You’ve seen it: “Gender Justice Is a Climate Issue!” Etc.

The Daily Upside writes:

As the days grow darker and colder, cuffing season is upon us, and that’s resulting in some strange bedfellows.

Carbon-free electric car maker Lucid is deepening its relationship with its largest investor, Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, which manages money for the world’s second-largest producer of ozone-killing oil after the US.

Pollution from oil consumption is an environmental problem, and ozone depletion is an environmental problem, but they are not the same problem. In fact, automobile fumes are a problem in some places because they produce ozone—and it’s good to have ozone up there in the ozone layer, but bad to have it in a haze over Los Angeles.

But this is “Words About Words,” and so I ask:

What in Hell is “cuffing season”?

I had never heard the expression, but it apparently is pretty common. “Cuffing season” refers to the tendency of some people to enter into new romantic relationships in the late fall or early winter—relationships that aren’t necessarily meant to last but that will provide some companionship on cold winter nights and at the holidays.

In a different English usage, to get cuffed means to get punched, to “get smacked upside the head.” Which is one thing that might happen if you make it too obvious to someone that they are only a space heater with benefits.

Further Wordiness …

Boxing Day.

Also…

The man was found stabbed Sunday shortly after 12 a.m., following a report of an assault in the area of York Street and University Avenue. The man was taken to a nearby hospital where he later died, police said. Authorities did not release the man’s name pending family notification.

Reminder: There is no such time as 12 a.m. There is noon, and there is midnight. We have perfectly good words to indicate these times of day—avail yourselves of the benefit!

Elsewhere

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can see my New York Post columns here.

In Closing

I wish a merry Christmas and a happy and prosperous new year to my friends and readers—groups that, happily, overlap quite a bit. I am grateful for all you do for me and for my colleagues, and I thank you on my own behalf and on behalf of the Dispatch crew.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.