In a recent discussion on The Dispatch Podcast, Sarah Isgur raised the question of which set of pardons and commutations were worse: Donald Trump’s pardons of the January 6 criminals or Joe Biden’s clemency extended to violent gangsters who had, among other things, tortured people with boiling water in order to extract information about drugs or money they wanted to steal. Neither Steve Hayes nor Jonah Goldberg wanted to answer the question, though Sarah did offer an answer—the wrong one: that Biden’s pardons were worse.

Sarah offered good, humane reasons for her view, beginning with the often elided (and not infrequently obfuscated) facts about these supposedly nonviolent offenders, who in many cases are anything but that—there is a big, big difference between being a nonviolent offender and being a violent criminal who simply was convicted on charges separate from the violence. E.g.:

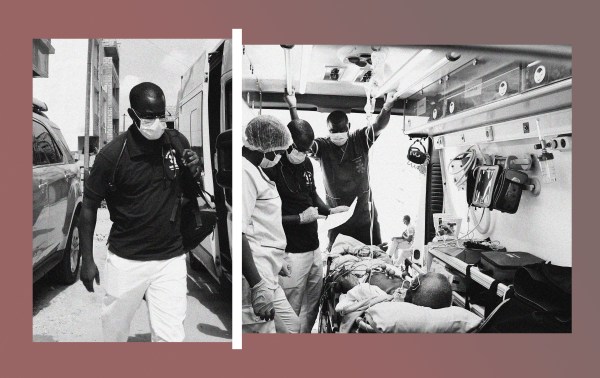

[Genesis] Whitted, 28, of Fayetteville, was found guilty in October. [Robin Pendergraft, criminal chief of the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Raleigh] said Whitted and his associates engaged in drug trafficking, home-invasion robberies, car hijackings, shootings and financial fraud. Their crimes sometimes involved innocent victims, she said.

Twice, Pendergraft said, Whitted and his accomplices poured boiling water on people until they disclosed the locations of drugs or money. On one occasion, she said, a Taser was used on a woman’s genitals. On at least one other occasion, she said, Whitted’s gang put a plastic trash bag over someone’s head until that person lost consciousness.

A woman who became a victim of the gang “described it as witnessing evil,” Pendergraft said.

Whitted trafficked in cocaine for nearly 10 years before he was caught by Fayetteville police and the FBI, who formed a joint task force. The task force spent months staking out the car wash and using an informant to buy cocaine from Whitted and his associates. Almost all of the cars that left the car wash were not cleaned, Pendergraft said.

Pendergraft said Whitted was able to escape punishment for years by obstructing justice and intimidating witnesses.

In 2009, Whitted was accused of murdering Kenneth Benjamin Underwood at a house on Wilma Street in Fayetteville. A main witness was set to testify against Whitted in 2011, until he claimed that he had been drinking the night of the murder and couldn’t identify Whitted as the shooter. The witness later died of a heart attack in jail, and Whitted went free. Police say his reputation on the streets grew after that.

His reputation on the streets was not that of a nonviolent offender.

Whitted wasn’t serving a long sentence for violent crimes—he was serving a long sentence for drug crimes. But that does not make him a nonviolent offender. It just means he was convicted on drug-conspiracy charges while his associates were convicted on those and additional charges, such as carjacking. As Sarah points out, there were people who testified against this guy, and I wouldn’t sell any of them life insurance. These are not trivial crimes.

But the crimes of January 6, 2021, are far worse crimes. Ordinary murder has been with us since Cain, and the sorts of crimes undertaken by Genesis Whitted and his associates are, while horrifying, common as dirt. In a free republic, crimes against the state (which are crimes against the public order) are much more serious and should be taken much more seriously. A common criminal who steals $500 should probably get a relatively light sentence; a municipal official who accepts a $500 bribe should do real prison time. A man who kills another man in a fight over drug turf or a woman or an insult is a common criminal; a man who assassinates a judge or murders a witness in a political-corruption case is an extraordinary kind of criminal. The common criminal victimizes one person at a time; the political criminal victimizes society as a whole, undermining its institutions and—not incidentally—making it more difficult to deal effectively with the common sort of criminal.

While the riot and the vandalism at the Capitol were the less-important half of Donald Trump’s attempted coup d’état following his loss to Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election, they were nonetheless part of a wider effort to negate the election and illegally install Donald Trump in the White House instead of the man elected president. That was, to put it in the plainest possible terms, an attempt to overthrow the government of the United States of America. That was the goal of January 6 and the end game of Trump’s various pretextual challenges to the legitimacy of the election. Trump’s sycophants and apologists wave their hands and wanly offer that he did not get very close to achieving his goal—but a stupid and incompetent coup-plotter is, in addition to being stupid and incompetent, a coup-plotter. Every member of the Trump administration, from J.D. Vance to Pam Bondi to the lowliest appointed flunky, all of the administration’s congressional allies, its enablers in the Republican Party, and every poor excuse for a citizen who voted to return this would-be caudillo to office in 2024 is, at some level, an accomplice to that crime.

But we operate, for now, under the rule of law in these United States, and, while guilt by association is a perfectly valid way of looking at the world in certain circumstances, we don’t put people in jail for that. We put them in jail after they have been investigated, charged, and convicted in a court of law, with all the benefits and privileges we rightly give to the accused in our system. The people Trump has pardoned or offered commutations to were convicted, by real juries in front of real judges in real courts, of real crimes, not of having bad political opinions or disreputable associations. As it happens, they committed these violent crimes on behalf of Donald Trump, whose contempt for the law is comprehensive. And his contempt is nowhere more evident than in these pardons.

A free society has to defend itself with the means it has at its disposal. Just as we have elections as a substitute for war, we have criminal trials as a substitute for vendettas, private revenge, and freelance political violence. And freelance violence, on a larger scale, is what we are going to end up with if people lose confidence—for good reason—in the credibility of our criminal-justice system.

From that point of view, Biden’s pardons related to political corruption (involving his family members) were worse from a republican perspective than were his acts of clemency toward more ordinary drug dealers and gangsters; by the same token—and Sarah’s sentimentalism notwithstanding—Trump’s pardons of the January 6 criminals were far worse than his predecessor’s last-minute coddling of the leaders of a Bloods faction in Fayetteville, North Carolina. We’re always going to have gangsters—the question is whether we are going to have a credible means of dealing with them. Trump’s actions are an assault on the legitimacy of American governance per se and on the state per se. This should be something like Dennis Miller’s description of U.S. national security policy: an incredibly long fuse at the end of which is a very big bomb. Americans have freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, the ability to petition their government for redress of grievances, the vote. That’s a very large field for political action. This isn’t some repressive backwater where people have to wage literal war against the state to reform anything. And when Americans resort to political violence, the full force of the state should come down on them. Even heroic practitioners of civil disobedience expect to go to jail—that is part of the civil-disobedience deal. And yet our rioters and coup-plotters walk free—indeed, one of them inhabits the highest office in the land. That is some shameful stuff.

Economics for English Majors

One brief observation this week. When it came to energy policy, the Biden administration was extraordinarily hostile to U.S. oil and gas interests. I’ll have a good deal more to say about that in a future report. But, hostile as it was, the Biden administration was also generally incompetent. It was able to inconvenience the fossil-fuel companies and cost them a great deal of money, but, as I noted last week, the interesting fact is that more people were employed in oil and gas at the end of Biden’s term than at the beginning of it.

Words About Words

I am indebted to my old friend and colleague Charles C.W. Cooke for reminding me of the term “Gish gallop” on a recent edition of The Editors podcast over at National Review.

What’s a Gish gallop? Wikipedia knows:

The Gish gallop (/ˈɡɪʃ ˈɡæləp/) is a rhetorical technique in which a person in a debate attempts to overwhelm an opponent by presenting an excessive number of arguments, with no regard for their accuracy or strength, with a rapidity that makes it impossible for the opponent to address them in the time available. Gish galloping prioritizes the quantity of the galloper’s arguments at the expense of their quality.

The term “Gish gallop” was coined in 1994 by the anthropologist Eugenie Scott who named it after the American creationist Duane Gish, dubbed the technique’s “most avid practitioner.”

The Gish gallop is a close cousin of the Hannity litany, which will be familiar to (for our sins) viewers or listeners of Sean Hannity’s programs, in which the Fox News host will, when there is a conversational lull or the need for something resembling a thought—both prospects clearly horrify the man—begin reciting a list of the sins, real or supposed, of his target. It is really something to listen to: If he doesn’t know what to say in a discussion of, say, climate policy, he’ll just start listing Democratic misdeeds, and suddenly, we’re on “Russia Russia Russia.”

This is the Golden Age of the Gish Gallop, I suppose. It is, as Charles notes, Donald Trump’s political strategy: Just keep throwing stuff out there and trust that the volume of stuff—the “avalanche of bulls—t,” as Marla Singer put it—will overwhelm critics’ ability to respond to it.

I have noted a similar phenomenon from time to time when reviewing books. I trust John Podhortez and Commentary will not mind my quoting at length from a years-old review, in this case of Bootstrapped by Alissa Quart.

There are a few different ways to go about reviewing a book as ignorant and illiterate as Alissa Quart’s Bootstrapped: Liberating Ourselves from the American Dream. The first and easiest would be simply to catalogue its errors, which are not incidental but fundamental to its argument: namely, that Americans are in thrall to a national myth of extreme individualism, which distorts our culture and produces bad public policy.

That myth, Quart writes, “has fed into the extreme rhetoric and actions of everyone from robber barons of yore”—of yore, of course, because the author will forgo no cliché—“to Reagan Republicans.” Extreme rhetoric and actions? Quart quotes Ronald Reagan in the next sentence and offers an example of the cruelty she is talking about: “‘The size of the federal budget is not an appropriate barometer of social conscience,’ Ronald Reagan said, as he used his metaphorical buzzsaw to take apart welfare, coming up with a whole language to demean those who were dependent on state monies, including ‘welfare queens.’” I suppose that there is some difference of opinion possible in the question of whether the cited rhetoric is really extreme, though “the size of the federal budget is not an appropriate barometer of social conscience” seems to me pretty mild stuff.

But there isn’t really any room for difference of opinion when it comes to whether Reagan should be credited with “coming up with” the term “welfare queen.” It seems to have first appeared in Jet, a black-oriented magazine that used the term in a story about a white woman, the infamous Linda Taylor of Chicago. She was investigated for welfare fraud in the early 1970s after reporting the theft of $14,000 in cash and furs to police detectives, who were “intrigued,” as Jet put it, “by the fact that she owned three apartment buildings, two luxury cars, and a station wagon.” Taylor was a practically cinematic character, and her story did very much suggest that oversight of welfare programs in the 1970s was, precisely as Reagan charged, something less than robust.

We also may consult the historical record to answer the related question of whether Reagan did, in fact, “take apart welfare.” Never mind that presidents have very little control over federal spending or that it was, in fact, Democrats who controlled the House and its appropriations powers for the entirety of the Reagan administration, as they did for all but two of the Congresses between the end of the Hoover years and the middle of Clinton’s first term. The thing is, there weren’t any cuts in welfare spending: The price tag on means-tested social programs (what’s usually meant by “welfare”) increased by about 10 percent during the first Reagan term and then by about 14 percent in the second term, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research. Spending on entitlements such as Social Security grew a little less slowly; Social Security spending grew by about 15 percent across both administrations. Which is to say, programs for the poor saw more robust spending increases than did middle-class programs such as Social Security—as the NBER puts it, the Reagan administration’s welfare-reform efforts “sought to reduce payments to those with relatively high incomes.”

The foregoing paragraph illustrates the problem with the catalogue-of-errors method of reviewing such a book. While the author’s distortion consists of only nine words (“he used his metaphorical buzzsaw to take apart welfare”), correcting it took, in this case, 364 words. The problem with online disinformation is that you cannot counteract it as quickly as troll farms can manufacture it, and the problem with many modern nonfiction books and much contemporary political journalism is more or less the same. I’d hate to think of our friends over at HarperCollins (which was kind enough to publish one of my books some years ago) as a kind of low-tech troll farm, but they sure as hell don’t seem to have a lot of fact-checkers over there. Almost the first checkable major claim made in support of the author’s thesis is demonstrably false, obviously false, and, to anybody with even a little bit of knowledge about the era in question, ridiculously false.

The enterprise of fact-checking lately has come into disrepute in some quarters—not least those with the least use for facts.

And so the galloping nonsense gallops on.

Elsewhere

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can see my New York Post columns here.

You can check out “How the World Works,” a series of interviews on work I’m doing for the Competitive Enterprise Institute, here.

In Closing

Our triplets celebrated their first Christmas and, recently, their first birthday. At some point, I will write up the story of their birth and the pregnancy before it, but, for the moment, I will note only that it was difficult, and that, at one point, the most authoritative medical opinion we had was that we were likely to lose all three boys before birth. Nothing of the sort happened, and they are healthy, thriving, inquisitive, mischievous little men, as is their big brother. We go through a dozen eggs most days and more diapers than I want to think about. My mornings still start before 5 a.m., though the little ones are starting to sleep a bit later more consistently, and my older boy, like his mother, prefers to wake up gently and gradually. For reasons of privacy, I cannot publicly name a few people I would like to thank for their help—from prayers to more practical assistance—over the past year and the nine months before. In particular, the two churches my family has been associated with during that time both have been models of Christian community, even when we were new to one of them and they barely knew us.

That mattered enormously to me, personally. I am accustomed enough to most of the hard feelings that are incidental to a life like mine—anger, resentment, disappointment (not least in myself), etc.—but I did not have very much experience with fear. That is not because I am particularly brave but simply because I live in a very prosperous and peaceable country in which real fear doesn’t play much of a role in an ordinary man’s life. But I was afraid for my sons and, because of that, for my wife and for myself. There are many things I think I could endure, but I am not sure I could have endured that. Fear is, of course, the beginning of wisdom.

I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at morning striding behind you

Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.

My Christian friends sometimes tell me, “God doesn’t give you more than you can handle,” but that is—forgive me being plain about it—a lie, and everybody knows it is a lie. People end up utterly crushed by their circumstances and by events beyond their control all the time. It is the most normal thing in the world. I know myself pretty well. (There are other things that would be a lot more fun to know.) I know where to find the fear in this handful of dust.

And I know that when people offer you their prayers, it is because that is what they have to offer. It is fashionable to sneer at that just now: “thoughts and prayers,” etc. But we should not let the banality of verbal expression, which is common to most people, taint the thing being talked about, which is by no means banal or meaningless or pro forma. It is not the case that there are times when prayers are all we have—it is the case that prayers are all we ever have and all we ever have had. “For he that is mighty hath done to me great things; and holy is his name. And his mercy is on them that fear him from generation to generation. He hath shewed strength with his arm.”

(I do not think it is the case that “all generations will call me blessed,” but they would, if they knew.)

Men like to think of ourselves as having and exhibiting strength, but that is another lie we tell ourselves. (I will show you positively neurotic self-delusion in a handful of dust.) Push on that a little bit and you’ll find that supposed strength is less solid even than those “thoughts and prayers” people roll their eyes at. We have very little to get by on beyond grace and the love of our friends and the halting hope that these will be enough.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.