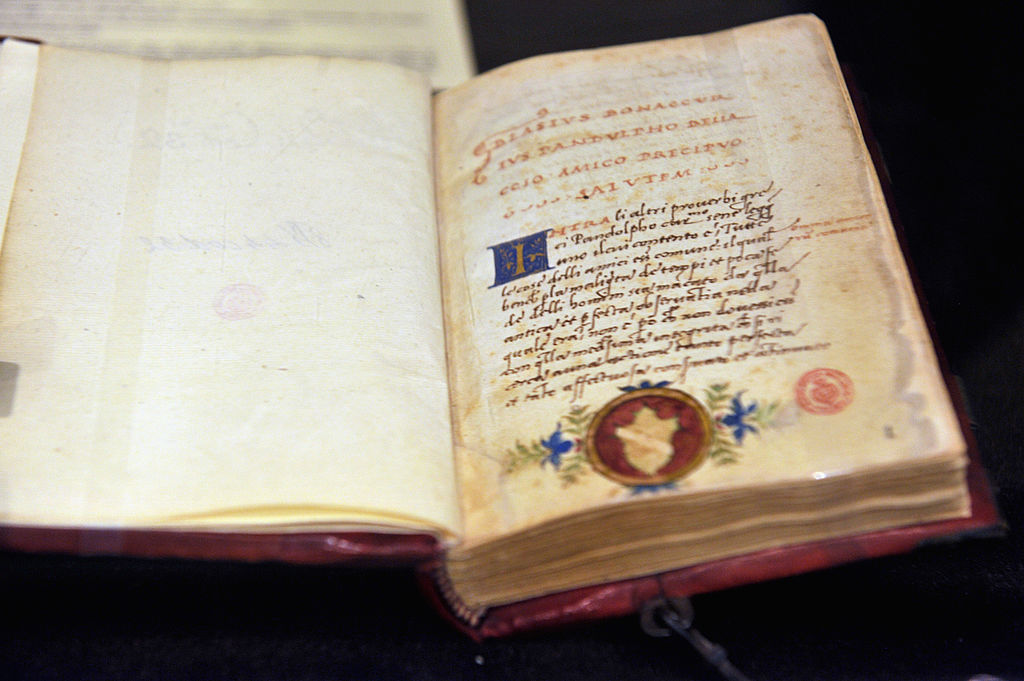

In his great but now neglected 1943 book The Machiavellians: Defenders of Freedom, James Burnham—also author of The Managerial Revolution and an important early figure at National Review—argues that Niccolò Machiavelli, the famous and infamous Florentine political theorist, is misunderstood. Burnham insists that Machiavelli wrote about politics in an amoral way not because he was an amoralist but because he was attempting to apply something like the scientific method to the study of politics. In Burnham’s estimate, the moral prescriptivists in politics are something like a doctor who tries to treat cancer by expressing his disapproval of cancer, whereas Machiavelli, to extend the metaphor, was more like an oncologist attempting to understand how the disease actually works. Though he was himself a republican, Machiavelli addressed his most famous advice to The Prince, both because princes were what were available to him and because he believed that his own political project, the unification of Italy, could be achieved only by monarchical means. Burnham asserts:

Science limits the function of goals or aims. The goals themselves are not evidence; they cannot be allowed to distort facts or the correlations among facts. The goals express our wishes, hopes, or fears. They therefore prove nothing about the facts of the world. No matter how much we may wish to cure a patient, the wish has nothing to do with the objective analysis of his symptoms, or a correct prediction of the probable course of the disease, or an estimate of the probable effects of a medicine. If our aim is peace, this does not entitle us, from the point of view of science, to falsify human nature and the facts of social life in order to pretend to prove that “all men naturally desire peace,” which, history so clearly tells us, they plainly do not. If we are interested in an equalitarian democracy, this cannot be a scientific excuse for ignoring the uninterrupted record of natural social inequality and oppression.

For Burnham, sentimentality is a species of dishonesty. The term “political science” is a misleading one—the study of politics is not a science, and “political science” belongs to the great catalog of pretentious pseudosciences and newfangled “-ologies” such as “social science” and “sociology,” part of the great 19th century linguistic inflation that gave us terms such as “social worker.” Nevertheless, it is worthwhile to aspire to a style of inquiry and analysis that is, as the word is used by Burnham, scientific. (I suppose “economic science” is useful for distinguishing what Paul Krugman did from what Paul Krugman does.) Burnham’s “scientific” cast of mind is certainly a welcome palate cleanser for the early 21st century reader of political journalism, who is force-fed a diet of pure high-grade hooey like a goose being subjected to gavage, a nasty process that at least has the benefit of producing foie gras. (Modern American political discourse produces an entirely different kind of animal product.) Burnham stated his ambitions plainly in the subtitle of The Managerial Revolution—he wanted to communicate “what is happening in the world.” Machiavelli, he argued, wasn’t the wicked schemer in the caricature—he was more like something somewhere between a responsible reporter and an honest academic.

In that spirit—and as the 2024 presidential election gets dreadfully under way in earnest—it is a good time for a little Burnham-and-Machiavelli-inspired look at “what is happening in the world,” or in our little corner of it.

For Machiavelli, the study of politics is the study of men competing for power. It is not that these men competing for power do not have morals, principles, ideologies, religions, fine aspirations, or any of the other transcendent possessions that we treat as imparting worthiness to politics—but Machiavelli simply was not studying these except insofar as they entered into his main field of inquiry. Think of it like economics: The economic factors at work in the business of producing and selling pornography or manufacturing Kool-Aid are very much like the economic factors at work in the business of printing and selling Bibles or manufacturing baby formula, but, if economics is what we are talking about, we don’t have to interrupt ourselves every five minutes to remind everybody that we prefer Bibles or baby formula to pornography or Kool-Aid.

Behind all of the Kulturkampf angst and wailing, all the talk about gun control, critical race theory, Christian nationalism, abortion, Elon Musk, climate change, and every other creaky politico-cultural fault in the United States, there is a contest for power. The people who generally clump together under the tendency of progressivism are not all college-educated, high-income, urban and suburban professionals, but those well-off people are the heart and soul of progressive politics and of the Democratic Party—more to the point, they hold most of the associated political and economic power. College-educated urban professionals do pretty well economically, socially, and politically, but they do not hold as much political and social power as they think they should.

While Gallup typically finds Democrats enjoying a small advantage in party-identification (three percentage points in the most recent poll) that modest advantage typically disappears or even reverses itself once independents (who, on paper, outnumber both Democrats and Republicans) are pressed on the issue. But, as Democrats are happy to point out, no Republican has won a majority of the total vote in a presidential election in a generation—come the next presidential election, it will have been 20 years.

Presidents George W. Bush in 2000 and Donald Trump in 2016 not only failed to win majorities, they were elected while winning fewer overall votes than the Democrats running against them. (It is easy to make too much out of this, of course: If we had direct, popular elections for president, then Republican candidates and voters in big states such as California probably would behave differently than they do now.)*

But the fight over the Electoral College is not only about control of the White House. It is symbolic of progressives’ broader frustration at their ability to secure what they believe to be their rightful place in society. Democrats and progressivism prevail in almost every major U.S. city, in the media, in the elite universities, at the commanding heights of business (Silicon Valley, Wall Street, Hollywood), etc. If you are a Democrat, you can graduate from a good law school, go to work for a big technology company, volunteer on a bar association committee, publish a bestselling book, and do interviews with the New York Times and the Washington Post about it without ever having to worry about running into a Republican in the course of any of that business. But Democrats’ political power falls short of the progressive elite’s social and economic power.

Democrats prevail in the cities, where the people are, and they especially prevail where the money is: The economic output of the average House district represented by a Democrat is almost 50 percent more than that of the average Republican-represented House district, and the difference is growing: In 2008, the average outputs of Democratic and Republican districts were $35.7 billion and $33.2 billion, respectively—but, 10 years later, the Democratic average had swelled to $48.5 billion, while the Republican average dropped a bit to $32.6 billion.

Conservatives who have a little bit of imagination might be able to appreciate, against their natural inclination, how it is that progressives feel entitled to political power and social status.

But the American constitutional order is non-majoritarian in many important ways and anti-majoritarian in others; and, contrary to all that talk about “oligarchy” from Sen. Sanders, the United States’ federal character makes it effectively impossible to purchase a national consensus—ask Michael Bloomberg how much money he has wasted trying to export New York progressive priorities to the rest of the country by means of various political projects. And so, even with all that money and power, and even with typically bigger turnout on Election Day, even with Harvard and the New York Times, Democrats still couldn’t get Merrick Garland on the Supreme Court over the brass-fortified obstruction of a single wily parliamentarian from Kentucky. They cannot prevail on the matters of gun rights or abortion, or on many other political issues. They do not win as many presidential elections as they expect to. As a social matter, they cannot keep Donald Trump off of Twitter, they cannot impose the wide-ranging speech restrictions they would prefer, and they cannot even get MSNBC’s ratings above Fox News’ ratings. They cannot confidently vote themselves a multibillion-dollar bonus in the form of student-loan forgiveness. They are having scant luck telling red-staters what kinds of cars to drive. They couldn’t make Ghosterbusterettes happen, much less Barack Obama’s post-presidential career as a saccharine documentarian.

Democrats are something like the crown prince waiting around for the king to finally die. They stand ready to inherit the kingdom and have big ideas about what they want to do with it, but they have not yet arrived at the state to which they aspire and that they feel is rightfully theirs. Republicans are in the opposite position, strongest in those places that have been economically bypassed (those former Rust Belt factory towns) or socially eclipsed (small towns and rural areas). Both parties appeal to well-off people, but in different ways: Democrats do best among high-income people in high-income places (finance workers in Manhattan, tech workers in Palo Alto) whereas Republicans do well among high-income people in relatively low-income areas (farmers, rural and exurban business owners); both parties also have low-income constituencies sharply divided by race, sex, religion, and geography. Both parties are characterized by self-interested elites that practice perverse and often hypocritical patron-client politics: Well-heeled big-city Democrats will fight against school choice for poor African Americans while exercising their own choice to select private schools for their own children and go to great lengths to immunize their own neighborhoods from crime and vagrancy; Republican tribunes of the plebs will do whatever it takes to fight drugs, short of demanding personal responsibility out from nice white people, and they care a great deal about industrial jobs they’d never dream of seeing their own children take. Each party knows that its best friend on Election Day is the revulsion its partisans will feel for the other party.

And it is revulsion—hence the dream of separation. It is natural to seek to separate ourselves from that which we find revolting. It may be necessary to dress up the elimination of effective opposition as a defense of “democracy,” the times being what they are. But the program remains the same. From Nathan Newman in The Nation:

Twice in the past 20 years, a GOP candidate who lost the popular vote took the presidency—and 2020 came uncomfortably close to making it the third time. A minority of the population controlled the Senate for the past six years, during which, in combination with a minority-elected president, it packed the Supreme Court with a supermajority of Republican justices. Our current constitutional arrangements are not just undemocratic; they starve blue states financially, deny human rights to their residents, and repeatedly undermine local policy innovation.

Given the undemocratic power of the Senate to entrench its own minority rule, the threat of secession is the only viable route to restoring democracy and equal justice, not just for blue-state residents but for Americans in all 50 states who are hurt by our undemocratic political system.

Covid-19 has transformed an ongoing political irritant into a murderous political indifference that we can no longer ignore.

Democrats are rarely more honest about their actual political complaints than when they kvetch about blue states “subsidizing” or “bailing out” red states. (Never mind that this is a nonsense claim in many ways and, to the extent that it is true at all, it is the result of progressive policies, namely a highly progressive income tax and welfare programs.) The poor and nonwhite Americans whose votes give political power to rich white progressives should take note about what that complaint really means. For example: Progressives like to point to Mississippi as a red-state basket case. (And never mind that Mississippi was governed almost exclusively by Democrats until approximately 15 minutes ago.) It is true that Mississippi has a much higher poverty rate than does, say, Oregon. But: Mississippi has a lower white poverty rate than Oregon does, and Mississippi has about the same black poverty rate as Oregon does, and in both states African Americans suffer much higher poverty rates than whites, but Mississippi is 38 percent black and Oregon is 2 percent black. Mississippi has a lower white poverty rate than Maine does and a lower black poverty rate than Maine does, too, but Mississippi’s poverty rate is almost twice that of Maine, where there are about four black residents. The black populations of rich, progressive cities such as San Francisco have plummeted over the years. Progressives may turn their noses up at suburban gated communities, but they live behind gates, too—invisible gates made of money and degrees and 800-plus FICO scores. Of course that has implications that touch race (and immigration, and education, and much more) as much as wealth and income. For these progressives, diversity is a byword, not a lifestyle.

The red-state/blue-state dynamic is complicated by the fact that most “red” states and most “blue” states are, as a matter of political geography, almost exactly alike: The cities are strongly Democratic, the rural areas are overwhelmingly Republican, and the suburbs get more Democratic the closer they are to town and more Republican the closer they are to the countryside. The poor people who give Mississippi its relatively high poverty rate and its well-peopled welfare rolls are, disproportionately, not exactly classic Republican voters. (Not since the 1930s, anyway.) The difference is in the urban-rural mix and in the character of the suburbs—subtract Philadelphia or Pittsburgh, and no Democratic presidential candidate has a shot in Pennsylvania; conversely, if the rest of Texas becomes a little more like Houston or Dallas, Republicans can forget about it.

The political and social situation of blue cities in red states is politically complicated: Of the 10 U.S. cities with the highest murder rates today, eight are in states that voted for Donald Trump in 2016, but none of those cities is Republican-led, and they are, on average, 54 percent African American. When Republicans point to out-of-control crime, they are largely pointing to urban failures in Republican-controlled states. (Yes, there are a lot of Democratic mayors and city councils in those states, but Mike DeWine understands that his jurisdiction does not exclude Cleveland.) When Democrats point to relatively low federal tax bills and relatively high welfare outlays for residents of red states, they are highlighting the failure of progressive policies and Democratic governance going back nearly a century, especially with regard to racial disparities in education, income, and wealth. In that way, each party uses the shortcomings of its own policies to delegitimize, discredit, and pathologize the other. In many cases, that is only another way of instrumentalizing African Americans in the service of well-off white people and their parochial interests.

We have been here before. We are, in a sense, always here.

In 1957, William F. Buckley Jr. wrote a now-infamous editorial in National Review in defense of the efforts of white Southerners to keep African Americans from voting. Buckley’s racial rhetoric was regrettable, and he regretted it, but his anti-majoritarian sentiment was much more intense than any racial feeling to which he gave voice. While insisting that the South “must not exploit the fact of Negro backwardness to preserve the Negro as a servile class,” he argued that the “White community in the South is entitled to take such measures as are necessary to prevail, politically and culturally, in areas in which it does not predominate numerically. … The White community is so entitled because, for the time being, it is the advanced race. … If the majority wills what is socially atavistic, then to thwart the majority may be, though undemocratic, enlightened. It is more important for any community anywhere in the world, to affirm and live by civilized standards, than to bow to the demands of numerical majority.”

It is worth noting and emphasizing here that in the phrase “such measures as are necessary to prevail” included, by Buckley’s own admission in the piece, political violence, which goes a good deal further than we could dismiss with, “Well, those were different times”; on the other hand, the notion that African Americans required “advancement” was hardly controversial at all, and neither was that way of putting it, which was explicit in the name of the era’s premier civil-rights organization.

We don’t talk or—thank God, actually think—that way about race very much anymore, and Buckley’s anti-majoritarianism has gone so far out of fashion that members of elites are embarrassed to admit that they are any such thing while activists with distinctly minority vanguardist or special-interest agendas feel compelled to invent masses of popular supporters. (Ask Sen. Rubio and he’ll tell you that the American people demand, as with one voice, federal subsidies that keep sugar billionaires from being reduced to the degraded state of sugar hectomillionaires.) But it seems to me that we are nowhere near to having given up the view that the advanced people (not a race, but a supposedly meritocratic elite) are entitled to take such measures as are necessary to prevent the predominance of atavistic policies.

To heighten the impression of atavism is, in fact, the reason our politicians deal almost exclusively in caricature and communicate almost exclusively in cliché. When somebody denounces Mitt Romney as a fascist, what they are really saying is only: “My people are entitled to take such measures as are necessary to prevail, politically and culturally, because we are the advanced people.”

Burnham quotes one of his Machiavellians, Vilfredo Pareto, observing: “Whether certain theorists like it or not, the fact is that human society is not a homogeneous thing, that individuals are physically, morally, and intellectually different. … Of that fact, therefore, we have to take account. And we must also take account of another fact: that the social classes are not entirely distinct, even in countries where a caste system prevails.” In the contemporary political project, a great deal of effort is put into denying the differences among individuals (“You can be anything you want!”) while exaggerating the distinctions between social classes. Partisans believe in absolute political equality, and they also believe that half of the country absolutely must be ruthlessly stripped of political power and social status.

Burnham may not have the readership he should, but somebody has been reading Machiavelli.

The infamous Florentine himself might possibly blush at contemporary Democrats railing against “privilege” and demanding “social justice” in the service of a political agenda that calls for—if we may be plain about it—giving rich people more power, and in particular investing even more political power and social status in the most affluent people in the most affluent communities. And that really is what is at the heart of our current political situation: The ruling class rules, but not as robustly or as unopposedly as its members feel themselves entitled to rule.

So put that in your pipe and smoke it, Gaetano Mosca.

Also …

The Trotskyist writer Joseph Hansen reviewed The Machiavellians under the headline, “A Shamefaced Apologist for Fascism.” Well. The review is worth reading if only for such fools’ gold as this: “Marxism has proved theoretically (and partially in practice in the Soviet Union) that world economy, freed from [the] fetters of capitalism, will develop such prodigious productivity as to finally liquidate the age-old scarcity which has given rise to class divisions.” My recollection is that is … not what happened in the Soviet Union.

Reinhold Niebuhr reviewed The Machiavellians in The Nation. That was a different era of political journalism.

Economics for English Majors

Does Wall Street hate working stiffs? Demagogues insist that Wall Street does, and one sometimes—sometimes, almost—sees why.

“Why a Strong Economy Is Making Stock Investors Jittery,” reads the New York Times headline. Shouldn’t a strong economy be good for the stock market? In the long run, yes, of course. But in the short run—and we mostly live in the short run!—stock investors are worried that continuing signs of unusual strength in the labor market will persuade the Federal Reserve that further anti-inflation action is required. That means higher interest rates, and higher interest rates mean less economic activity—that is what they are supposed to achieve, anyway. If it gets more expensive to access money, then people spend less, businesses invest less, new projects and lines of production don’t get launched and nobody has to be hired to do that work, etc. Everything slows down a little bit (or a lot if the Fed gets it wrong), demand slackens, and prices go down, breaking the cycle of inflation.

There is a popular impression—and a rhetoric—that insists that the stock market and financial instruments are distinct from the “real economy,” and that finance is essentially a parasite of the “real economy.” There are times when it is useful to draw a distinction between the production of physical goods and services, retailing, transportation, etc., and the construction and exchange of financial instruments, but it is easy to make too much of this, too. Populists left and right love to heap scorn upon “financialization,” but populist economic claims are so reliably daft that categorical skepticism is appropriate.

Financial instruments (and financial services in general) give us a way to put prices on things that would otherwise be difficult or impossible to price, and they allow us to create (or extract) value from situations and services that would otherwise go unrealized. This has played an invaluable role in building the modern “real” economy. Modern financial services really begin in earnest with international shipping—Lloyd’s of London got its start as a kind of clearinghouse for marine insurance. In the earliest days of global trade, transaction costs were very high, and investors who put their fortunes into financing commercial voyages (or borrowed money to do so) could be entirely ruined by a single disaster at sea. Marine insurance gave traders a way to hedge their bets, and this most assuredly had a profound effect on the “real economy”—with insurance, there was a radical increase in the real economic value of a great many ships, commodities, manufactures, etc., because moving those things great distances was more practical and economical with insurance. But what insurers sell isn’t a tangible good—what they sell is the service of taking on a portion of your financial risk in exchange for a premium.

Because modern finance can be so arcane and opaque, it is easy for demagogues to claim that private-equity firms and investment banks and the like do not create any real value. This ignores a great deal of easily observable reality—for example, the fact that Goldman Sachs has customers, and that these customers are not coerced into doing business with Goldman Sachs but find value in the services they choose to pay for. These are, for the most part, financially sophisticated parties—perhaps it is the case that they are better positioned to judge the value that financial services firms create for them than Sen. Warren is, in spite of her illustrious career as an author of dopey get-rich self-help books with such titles as All Your Worth: The Ultimate Lifetime Money Plan.

A big part of finance is the exchange of risk. What that means, in practical terms, is the transfer of some risk from a party that cannot afford to bear it in its entirety to a party that can afford to bear it—for a price. We understand this intuitively when it comes to health insurance, but, for some reason, many Americans grow skeptical of it when it comes to securities. Of course finance can be done corruptly or, possibly worse, incompetently (see the unpleasant events of 2007-08) but so can brain surgery or teaching kindergarten. If you want to understand what is actually happening, you could do worse than to begin by asking what it is that the people who are paying are getting for their money, or what they think they are getting.

Without financial services, there’d be a good deal less “real economy” out there to enjoy.

Words About Words

In the New York Times story about nervous stock investors, two of the gentlemen quoted are named Eric Johnson and John Williams. Neither one is a famous guitarist: not this Eric Johnson (and not Eric Johnson the mayor of Dallas) and not that John Williams. (I assume both guitarists have healthy investment portfolios.) I imagine that John Williams the guitarist sometimes has to explain to people that he is not that other musical John Williams. It was a longstanding joke that the bow-tied senator from Illinois and Edie Brickell’s husband were always getting mistaken for one another—both of them being named Paul Simon. (About twice a year, somebody sends me a screenplay or a pitch meant for this guy. There are a lot of Kevin Williamsons out there, which is one reason I use my middle initial, like Yngwie J. Malmsteen, who probably gets confused with a lot of Yngwies.) The CIA employed at least two William Francis Buckleys over the years—one ended up making a career in journalism, the other was kidnapped, tortured, and murdered by Hezbollah.

We don’t have a very good word for this situation. Formally, a person who shares the name of another is his namesake, but we usually use namesake in a situation in which a person or thing is intentionally named after another person or thing—namesake can refer to the party of either side of the relationship. A related word is eponym, a person after whom something is named or believed to be named: Lou Gehrig’s disease is one of many eponymous maladies, other examples of which include Lyme disease and Kaposi sarcoma. The extraordinary hoarding habits of some elderly people have been variously named Diogenes syndrome, Havisham syndrome and Plyushkin syndrome, depending on whether the observer has been reading Dickens or Gogol or for some reason feels compelled to defame an ancient Greek philosopher. (Far from being a hoarder, Diogenes famously had almost no possessions at all and slept in the marketplace like some nasty hippie in Portland.) The rock band REM, having a laugh at the tradition of bands issuing eponymous albums, called one of its greatest-hits records Eponymous.

Some Spanish-speakers use tocayo for a person who happens to share one’s name (the word is Náhuatl in origin), and a few other languages (including Swedish) have a word for an accidental namesake, but English, as far as I know, doesn’t quite have what I’m looking for. Some people have suggested “name-twin,” but I cringe even typing it.

Elsewhere

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can see my New York Post columns here.

In Closing

Fox News is going to have to change its name to Fox Horses–t.

* Correction, February 21: This column originally misstated the popular vote in the 1892 presidential election.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.