John Adams / Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States, 1787“When the three natural orders in society, the high, the middle, and the low, are all represented in the government, and constitutionally placed to watch each other, and restrain each other mutually by the laws, it is then only, that an emulation takes place for the public good, and divisions turn to the advantage of the nation.”

Of course we shouldn’t trust the people. That’s one of the basic American ideas.

As John Adams saw the political world, there were essentially three main forms of government—monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy—each with its own particular deficiencies. You’ll be familiar with his famous 1814 letter to John Taylor:

I do not say that Democracy has been more pernicious, on the whole, and in the long run, than Monarchy or Aristocracy. Democracy has never been and never can be so durable as Aristocracy or Monarchy. But while it lasts it is more bloody than either.

… Remember Democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes exhausts and murders itself. There never was a Democracy Yet, that did not commit suicide. It is in vain to Say that Democracy is less vain, less proud, less selfish, less ambitious or less avaricious than Aristocracy or Monarchy. It is not true in Fact and no where appears in history. Those Passions are the same in all Men under all forms of Simple Government, and when unchecked, produce the same Effects of Fraud Violence and Cruelty. … Individuals have conquered themselves, Nations and large Bodies of Men, never.

Adams’ views, and those of similarly inclined thinkers, were influential at the Constitutional Convention, which Adams himself did not attend. (He was doing his country’s business at the Court of St. James’s at the time.) Adams had no interest in utopian ambitions or in what Michael Oakeshott would later call “rationalism in politics”: the superstition that enlightened men, sufficiently empowered, could simply cogitate a superior world into existence. Adams, like many of the other founders, was a student of the classics (imagine a contemporary American politician beginning a disquisition with “Let me proceed then to make a few observations upon the Discourses of Plato and Polybius”), and what he learned from his studies of the wise men and the great civilizations of the past was that the project of organizing life was a story of—at best—temporary success followed by inevitable failure.

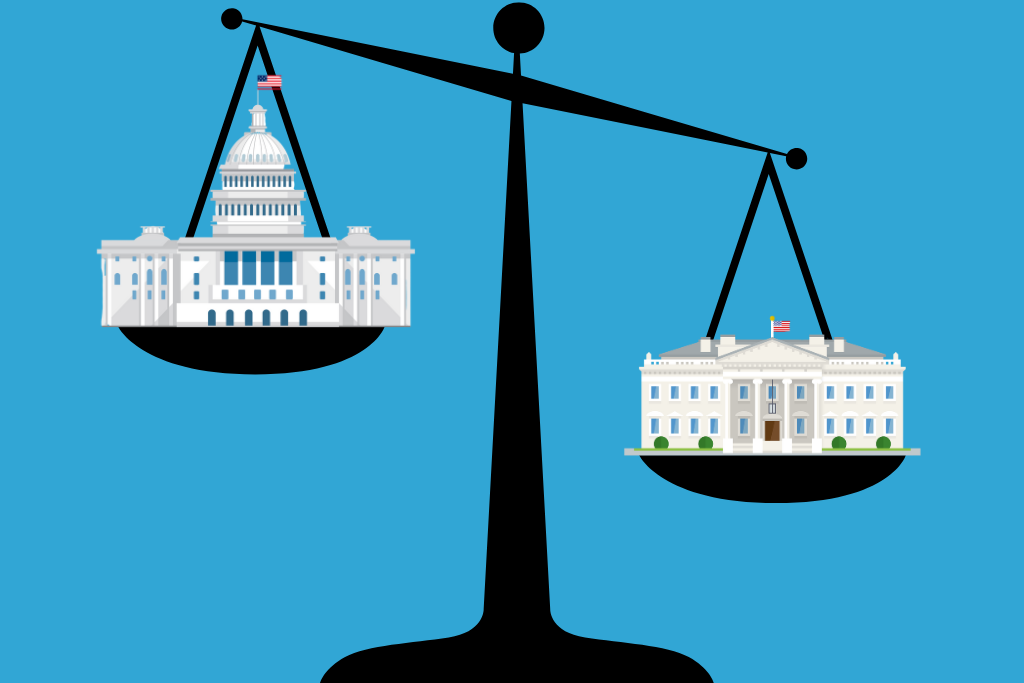

Adams did not dream of setting up perfectly aligned spheres of Platonic perfection—he wrote and spoke of “balance” and “equilibrium.” Like all conservatives, he understood and cherished the organic diversity of a healthy and flourishing society (“the proliferating variety and mystery of human existence, as opposed to the narrowing uniformity, egalitarianism, and utilitarian aims of most radical systems,” as Russell Kirk put it) and believed that classes, orders, and communities were real, enduring things. While the French saw their revolution descend into terror and oppression in its quest to build what would later be called a “classless society,” Adams and the American founders worked to build a government that not only took account of classes, orders, regional variety, quirks, eccentricities, and distinct interests but that was intentionally designed to use these differences to the advantage of the nation as a whole. Factions and parties were, in Adams’ view, both destructive and inevitable—the only reasonable way to peace and security was to organize rivalry, setting groups in opposition to one another and, in that way, harnessing competition for the service of the public good.

It is to James Madison that we mainly owe the final form of our Constitution, but you can see the mark of Adams’ mind on it. “The king, the aristocracy, and the people, as soon as ever they felt themselves secure in the possession of their power, would begin to abuse it,” he wrote. But a president, a senate, and a house of representatives could be constitutionally constrained in such a way as to avoid any of them ever being “secure in the possession of power.” The senate, in Adams’ imagination, would be a kind of gilded cage for the aristocracy—a place from which they could exercise real power, of course, but also a place in which their influence could be quarantined. Faced with the asymmetrical power and ambition of the high and mighty, Adams argued:

The only remedy is to throw the rich and the proud into one group, in a separate assembly, and there tie their hands; if you give them scope with the people at large or their representatives, they will destroy all equality and liberty, with the consent and acclamations of the people themselves. They will have much more power, mixed with the representatives, than separated from them. In the first case, if they unite, they will give the law and govern all; if they differ, they will divide the state, and go to a decision by force. But placing them alone by themselves, the society avails itself of all their abilities and virtues; they become a solid check to the representatives themselves, as well as to the executive power, and you disarm them entirely of the power to do mischief.

The Senate, as originally conceived, was a countermajoritarian institution, not only un-democratic but anti-democratic. Its job, as Adams saw it, was to protect the upper classes from being plundered by the lower.

The rich are people as well as the poor; that they have rights as well as others; that they have as clear and as sacred a right to their large property as others have to theirs which is smaller. … The rich, therefore, ought to have an effectual barrier in the constitution against being robbed, plundered, and murdered, as well as the poor; and this can never be without an independent senate. The poor should have a bulwark against the same dangers and oppressions; and this can never be without a house of representatives of the people. But neither the rich nor the poor can be defended by their respective guardians in the constitution, without an executive power, vested with a negative, equal to either, to hold the balance even between them.

And so the president, too, is meant to be a brake in our political system rather than an accelerator, whose greatest power vis-à-vis the legislature is the purely negative power of the veto.

And that is where Adams, and most of the rest of the founders, got it a little bit wrong—and where the better case was had by the Anti-Federalists, with their suspicion of a strong national government and the quasi-monarchical president at the head of its executive branch.

There is a reason that rule by a single, powerful man has been a norm—often so deeply fixed that nobody could even think to question it—in so many dissimilar political cultures across so many dissimilar centuries. The human instinct to submit to a powerful father figure, and to be comforted and protected by him, is at the foundations of both politics and religion. And while the legislature is divided and subdivided—between the houses, between the parties, among factions within the parties—the executive power is invested in a single man in our system. (A language note: With due respect to the certainly sore feelings of Kamala Harris, “in language as in life, ‘man’ embraces ‘woman’,” as the line attributed to Margaret Thatcher goes, though as a matter of fact the U.S. presidency remains a men’s club if not a gentlemen’s club.)

The president’s ambitions can remain focused and coherent in a way that the ambitions of the majority party in the House cannot. With its democratic character and elections every other year, the House was intended to be the receptacle of democratic energy, one part town hall meeting and one part constitutional drunk tank. Our founders wrongly thought the House would be the mover and that the Senate, the president, and, if it came to it, the Supreme Court would be the resistance to its movement. Think of a motorcycle: The accelerator keeps the whole contraption moving forward, making balance possible, but there are brakes both up front and in the rear for a good reason.

(Democracy: Wear a helmet!)

In reality, Congress as a whole has become sluggish. The Senate has been deformed both by its democratic makeover under the 17th Amendment (providing for the direct election of senators) and by the fact that at any given time 91 of its 100 members are getting ready to run for president. The House has proven unwilling or unable to deal with the complexities of life in a globalized and technologized world, its members dangerously insulated from their constituents by the growing size of House districts (now about 762,000, as opposed to about 34,000 in 1800), uncompetitive general elections, and the decline of the organized party power that so worried Adams et al. The presidency, by contrast, has grown larger and grander—driven in part by the psychological and cultural factors referenced above and by the theatrical quality of our public life—filling the void created by Congress’ slow abdication.

And so, from the point of view of Adams, our republic is both upside down and out of balance: We are using the brake for an accelerator and the accelerator for a brake. And such a brake as Congress can provide is not a thoughtful or deliberate one but only friction and confused inaction—less a brake than sand in the gears or a monkey wrench in the works.

People are sometimes shocked when I write that the American people cannot be trusted to govern themselves, that democracy is a two-cheers proposition at best, procedurally necessary only because it is the sole practical alternative to bellum omnium contra omnes. But these are not my ideas—and they are not new ideas. The belief that democratic power has to be limited and constrained by constitutional machinery that frustrates the passions of the demos in the interests of order and property is the basic American constitutional idea.

On the other hand, Vox populi, vox Dei is (despite its Whig associations) a creed of barbarism, rightly identified as such as far back as Alcuin, who advised Charlemagne to ignore those who cited it, insisting rightly that (to paraphrase) the turbulence of popular passion was never far from mass madness. (“Nec audiendi qui solent dicere, Vox populi, vox Dei, quum tumultuositas vulgi semper insaniae proxima sit.”) Of course, it is a fact visible to anyone with eyes to see that Vox populi, vox Dei is simply a place of retreat for moral cowards who do not wish to take personal responsibility for their own decisions—see Elon Musk, who likes to outsource decisions to “the people” when he can be sure they’ll go the way he wants them to.

Vox Dei? To the contrary, Adams argued that corruption and catastrophe could well come from giving too much power to the many as to the few:

The generation and corruption of governments, which may, in other words, be called the progress and course of human passions in society, are subjects which have engaged the attention of the greatest writers; and whether the essays they have left us were copied from history, or wrought out of their own conjectures and reasonings, they are very much to our purpose, to show the utility and necessity of different orders of men, and of an equilibrium of powers and privileges. They demonstrate the corruptibility of every species of simple government, by which I mean a power without a check, whether in one, a few, or many.

In that sense, our deformed and aggrandized presidency is the result of giving too much power both to the many—to the mass electorate that has overwhelmed the power of parties and other institutions—as well as to the few, in fact, to the singular, in the person of the president. The modern analog to the aristocracy, then, isn’t the Senate at all—it’s the bureaucracy, whose members are relatively small in numbers, elite in education and socioeconomic status (not baronial but well-off and, most significant, secure), and not subject to election. (The Supreme Court is more like the clergy of old.) The people, of course, are still the people, and still the same mob they’ve always been.

Adams’ anti-populism was well-founded and intelligent—and, as such, it was mocked and derided by the same class of smug rich people who always appoint themselves the champions of the common man: Thomas Jefferson, that great populist, could just about see the common man in the distance, laboring at the edge of his plantation, the mortal enemy of aristocratic privilege just barely making out the shape of the common man as he looked down from his commanding height over the bent backs of his slaves. Populism is, and always has been, a scam. And its ultimate end has always been the one Adams warned us about: “power without a check.”

If I may quote my own words from May 4, 2016: “Remember, you asked for this.”

Words About Words

I wasn’t kidding when I referred to the presidency as a “gentlemen’s club.” One of the unlovely ironies of our times is that “gentlemen’s club” is a euphemism for the sort of place men go to act in an ungentlemanly fashion. That isn’t meant as a blanket condemnation of strip joints—consenting adults and all that—but calling them “gentlemen’s clubs” is like calling a NASCAR race a course in defensive driving.

Rush Limbaugh used to joke that Bill Clinton’s presidential library would contain a strip club, but it is the current president-elect who is more closely associated with the skin trade: One of the few real innovations associated with any of his businesses was the decision to put a strip joint in the Trump Taj Mahal in Atlantic City, New Jersey. The brass pole went up in 2013. The bankruptcy came in 2014. It is now the Hard Rock Hotel and Casino, and still a dump.

Economics for English Majors

I have a crazy theory: Politicians would get less tripped up on economic questions (and many other kinds of questions) if they would tell the truth. It is generally accepted that the destructive inflation of the post-pandemic era put a mortal wound in Kamala Harris’ presidential campaign before it ever got off the ground. But imagine she had something along these lines in a speech or a debate or an interview:

Inflation? Yes, that’s probably been the biggest failure of our administration. We didn’t think it would be as bad as it was or that it would last as long as it did.

If you’ll permit me, I’d like to say a few words about that.

In the second quarter of 2020, the U.S. economy contracted by almost 30 percent. It was the most severe economic contraction in U.S. history, by far. For comparison, consider that in a single quarter, the U.S. economy shrank as much as it did from the beginning of the Great Depression in 1929 to the bottom in 1933. It was an unprecedented economic catastrophe. When the country got back to work in the next quarter, we saw the biggest spike in GDP in U.S. history, about 35 percent. That was a sign of resilience, but also an indicator of possible instability. We saw remarkably strong growth through the first year of the Biden administration, but we were back into negative territory by early 2022. That was not an easy period for Americans, and inflation made it hurt in a particularly immediate and urgent way.

What happened was this: When there is a big economic contraction, as there was during the pandemic, the usual strategy is to engage in stimulus spending to try to prevent the economy from going into a full-on recession, or, if there is a recession, to soften the effects of the recession and to shorten it. And, with stimulus spending, you’re flying in the dark a little bit. You don’t know what the exact outcome is going to be. Stimulate too much, and you get destructive inflation of the sort that Americans suffered through during the first part of the Biden administration. Stimulate too little, and you risk ending up with an unnecessarily long and deep recession.

I don’t want to shift blame—the sign on the desk says, “The buck stops here.” But it is worth keeping in mind that stimulus spending as a response to the pandemic was a bipartisan effort. Much of the spending that contributed to later inflation happened during the Trump administration and as the result of laws signed by Donald Trump and passed through Congress with Republican support. Some of you may remember that Trump wanted to have his own signature on those stimulus checks, as though he were personally giving Americans a gift out of his own pocket. It is not as though Democratic spending contributes to inflation and Republican spending doesn’t. It’s all baked into the cake.

So—risk inflation or risk a recession?

A recession isn’t just a blip on the GDP chart. A serious, deep recession could mean millions of people losing their jobs. It means businesses closing. And, when the recession is over, those businesses don’t just take up where they left off and hire those employees back. Losing businesses and jobs is destructive, and the effects over the long term are serious. To put it in stark terms, the choice we faced was between risking a situation in which Americans’ paychecks wouldn’t go as far as they used to and risking a situation in which millions of Americans—including some of you listening to this—would have lost those paychecks entirely.

And that has ripple effects: Businesses stop buying goods and supplies, they stop renting office space or commercial space, storefronts go vacant, contracts are broken. Families lose their homes when they can’t pay their rent or make their house payments. Banks and property owners and other businesses lose income, and they often pass those losses along to consumers or their employees. If there were some magical Goldilocks formula that would have ensured that we didn’t stimulate too little or stimulate too much, that would have allowed us to be confident that we could avoid both inflation and recession, then, of course, that’s the course of action we would have taken. But there is no way to know.

We wanted to avoid inflation, and we also wanted to try to spend some money in ways that would help families and communities who had been particularly hard-hit by the pandemic, who were going to need a little more help digging out. We saw that as a good investment, too. And so we leaned into the stimulus and risked inflation. And inflation is what we got. If we had tried it the other way, I might very well be standing here telling you why we had a terrible recession that resulted in millions of lost jobs and shuttered businesses. Instead, we’re talking about inflation. And none of us are happy to be talking about it, me least of all.

Did we get it right? Obviously not. I could talk about how we expected supply chains to recover more quickly than they did, about delays in the effects of stimulus spending, about the ineffable complexity of the modern market economy. But the fact is, we made a choice. We thought it was better to risk temporary inflation than the long-term damage done by a major recession. And, though it was much more persistent than we had expected, that inflation was temporary. That doesn’t mean we were right to downplay inflation as transitory. That doesn’t make it much less painful, and that doesn’t mean that prices that have gone higher are going to go back down in the near future. What we want is to use good economic policy, including tax reform, along with long-term investments in education and infrastructure, to help struggling families catch up to their grocery bills and, if I have anything to say about it, to get ahead a little bit, too.

I’m speaking to you about this honestly because I believe that Americans can handle the truth, that you are smart enough and civic-minded enough to be trusted with understanding the actual policy dilemmas that we have been dealing with. My opponent wouldn’t take the time to explain the policy questions to you in this way, because he can’t. He doesn’t understand them himself. And so he’s telling weird made-up stories about black people eating dogs and cats in Ohio.

In the long term, getting strong economic growth without high inflation is going to require some changes, including getting the federal government’s fiscal house in order. We have too much debt already, and our deficits remain too large. Addressing that problem is going to mean higher taxes on someone, and, under my proposals, that’s not going to be low-income or middle-class families—it’s going to be high-income taxpayers and businesses. I don’t expect them to like it. It’ll mean higher taxes on my family, too. But the alternative is either gutting Social Security and Medicare today or positioning the government for a fiscal crisis in the future that will make the pandemic and the inflation that followed look like a day at the beach. Putting off hard decisions doesn’t make them any easier. It just makes you a coward. And I don’t think we can govern this country with cowardice or with lies.

I won’t say that we’ve done everything right. You wouldn’t believe me if I said that, and you shouldn’t. Our record has been far from perfect. I don’t blame you for blaming me. But I trust you enough to present you with the facts of the case, believing that you will make the right decisions based on those facts rather than being stampeded into making a bad decision based on rage and anxiety and lies. Because that’s how we’re trying to do things. I trust you, and I’m asking you to trust me.

I’m not sure that is golden as political rhetoric, but it does have the benefit of being mostly true.

Elsewhere …

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can see my New York Post columns here.

Please subscribe to The Dispatch if you haven’t.

You can check out “How the World Works,” a series of interviews on work I’m doing for the Competitive Enterprise Institute, here.

In Conclusion

Another way of thinking about the outcome of the presidential election is this: Donald Trump received about as many votes winning in 2024 as he did losing in 2020: 74.2 million and change. Kamala Harris’ vote total was about 11 million short of Joe Biden’s. The United States hasn’t really taken a turn in a Trumpy direction, going by the numbers. What happened happened thanks to factors you’ve read me and a couple dozen other columnists writing about since at least 2023: Kamala Harris was a bad candidate who had never had a very impressive showing in a competitive election of any kind, who talks like a yoga teacher when she isn’t talking like the assistant dean of students, and who doesn’t seem to really believe very strongly in anything other than abortion rights.

In 2008, two out of three Hispanic voters voted for Barack Obama in a year of record Hispanic turnout, while 95 percent of black voters chose the Democratic candidate. Harris still won the majority of Hispanic votes, but only 55 percent; she won the majority of African Americans’ votes, with 83 percent. Harris won the majority of women’s votes, too, but only 53 percent. You need to do a lot better than small majorities if you want to get elected on minority-group support and on an edge with women—50-odd percent doesn’t cut it. And as we continue to progress in the great enlightened project of incorporating African Americans, Latinos, and other minority groups into the great vast vague lump of Americanness, those voters will become more like the majority of American voters: fearful, daft, and mediocre, to be sure, but also unlikely to give 95 percent of their vote to any particular candidate.

If you want to win an election as a practitioner of grievance-group identity politics, it’s a heck of a lot easier if you do what Donald Trump did and run, however moronically and dishonestly, on the grievances of the people who make up the majority of the country. It’s not that the United States isn’t ready to elect a black woman president—Condoleezza Rice didn’t want the job when it might have been hers. There’s a difference between a country that doesn’t want a black woman as president and a country that didn’t want this particular black woman as president. All Trump had to do was tread water, and he is a buoyant sort of presence, an apparently unflushable turd of a man.

Life goes on, this doddering republic endures, “put not your trust in princes,” etc.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.