Hello, and happy Saturday! I hope you are making some wonderful memories, taking some time off to relax, or otherwise enjoying the holiday break. The last thing I want to do is to disrupt your respite, so while this is a year-in-review newsletter, I’m not going to do a play-by-play. We all lived through it.

No, what I’d like to do in this last Dispatch Weekly of the year is highlight some of our deeper dives into a range of topics. I won’t say it’s a definitive list of our best work—that would be unfair to our reporters who churned out important daily campaign updates or The Morning Dispatch writers, who regularly put together quality reporting and analysis on a 24-hour timeframe. And considering we published thousands of newsletters and articles this year, I almost certainly forgot something! That said, we made a concerted effort this year to focus on bigger pieces and more in-depth reporting—stay tuned for even more in 2025!—so much of the work is worth revisiting.

We thank you for your support of what we’re building here at The Dispatch, and I hope you enjoy this last look back at a year that we knew would be crazy yet somehow managed to defy expectations.

When Donald Trump accused Haitian immigrants of eating pets in Springfield, Ohio—disinformation peddled by his running mate, Sen. J.D. Vance of Ohio—there was only one thing for us to do: Send Kevin Williamson to investigate. Even if you read this in September, it’s enjoyable enough to revisit.

Poor people have been coming to Ohio in search of jobs in its factories and warehouses for centuries: From the original New Englanders who settled in the Northwest Territory to the Scots-Irish to the Irish and Germans in the 19th century to the Haitians today, that story has been repeated over and over. At the turn of the 20th century, a majority of Cincinnati’s population consisted of those who either were foreign-born or were the children of foreign-born parents, mostly German. Naghten Street in Columbus, on the other hand, became “Irish Broadway” in the middle of the 19th century. The J.D. Vances of that era didn’t much care for the whiskey-drinking, potato-eating papists invading their cities, but they made good use of the canals and railroads built by those illiterate exotics from distant lands.

The guy who wrote Hillbilly Elegy understood all that. This asshole who is running for vice president, on the other hand …

Way back in March, when it became clear that Donald Trump would secure the Republican nomination for president and when Joe Biden appeared dead-set on seeking reelection, we published a rare staff editorial. While we have a policy of not making political endorsements, that doesn’t mean we couldn’t hand out a pair of non-endorsements:

Politicians respond to incentives. We’ve arrived at this point because the disaffected majority of voters who are fed up with today’s political climate have consistently held their noses and settled for candidates they don’t like who have been imposed upon them by the hyperpartisan fringes. In the United States, a shockingly small percentage of the overall electorate determines the two major parties’ nominees. The country will never return to the smoke-filled rooms of the past, but the tyranny of the most rabidly partisan doesn’t strike us as much of an improvement.

We understand and respect that Americans will respond to the dismal choice in front of them in different ways—for different reasons—but we encourage them to weigh their options carefully, clear-eyed about the potential ramifications of either man securing a second term and on guard against the natural impulse to justify their vote by turning a blind eye to the candidates’ obvious flaws. No matter who wins, we will desperately need as many people as possible who can still tell the difference between good and evil, right and wrong, truth and lie. In a democracy, such people are the only guardrail against tyranny.

It’s not easy to pick a single G-File to include in this roundup. But I’d be remiss not to share something about the story that dominated the 2024 election: President Joe Biden stepping down—extremely reluctantly—after his woeful debate performance in June exposed the extent of his decline. Jonah Goldberg wrote this before Biden withdrew from the race, so we know how the story ends, but it’s still a good read all these months later.

On one level deserve’s got nothing to do with it. But the perception of whether a politician deserves the heave-ho is vitally important. Voters and coalitional stakeholders care about that stuff because they have a reliance interest in party loyalty and cohesion. So, parties are supposed to stand with their members when they’re in a jam not necessarily because they deserve it, but because a certain amount of loyalty and solidarity is necessary to hold a coalition together.

But the loyalty and solidarity is supposed to go both ways. When politicians indulge their self-interest to the point where continuing to do so harms the party and they fail the cost-benefit test, they’re supposed to get out of the way “for the good of the party.” If they refuse to do so, the party is supposed to throw them overboard.

That’s what the GOP did to George Santos and what the Democrats have been trying to do with Bob Menendez. It’s what the Republicans should have done to Donald Trump a long time ago. And it’s what the Democrats should do with Biden and possibly Kamala Harris right now. But all of this would require having strong and healthy parties.

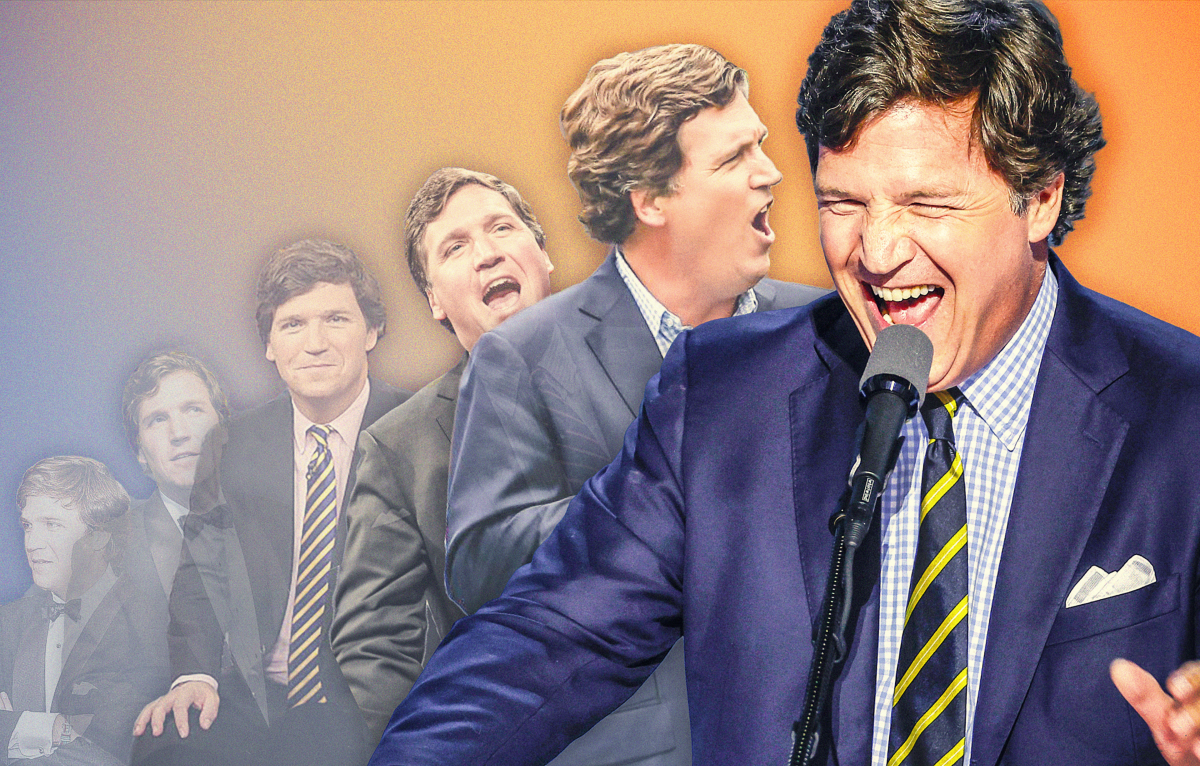

How did Tucker Carlson evolve from a buttoned-down magazine writer and sharp debater on CNN’s Crossfire to a mouthpiece for the virtue of Vladimir Putin’s Russia? Why did he go from debunking conspiracies to elevating them, from criticizing Alex Jones to appearing at events with him? John McCormack explained—or tried to—in this in-depth profile.

Becoming a TV superstar can have deranging effects on anybody, as Carlson noted in his 2003 book. “If running for office can encourage you to imagine millions of supporters [who don’t exist], hosting a show can entirely separate you from reality,” he observed. “If you’re not careful, you can permanently lose all critical distance from yourself. One morning you wake up, and you’re living in your own irony-free world.”

That could be the world Carlson is living in today.

In the hours of Tucker Carlson podcasts and interviews I’ve listened to for this article, the most disturbing thing I heard wasn’t any conspiracy theory. It was Tucker’s laugh.

No one who lives in the mountains expects to live through a hurricane. But the remnants of Hurricane Helene dumped 30 inches of rain on parts of eastern Tennessee and western North Carolina in late September, flooding rivers, washing out roads, and devastating entire communities. But while residents of Appalachia had little time to prepare, they had an important resource at hand when it came time to dig out: a strong sense of community. Our own Michael Reneau weathered the storm personally, then struck out to report on the recovery.

That pockets of Appalachia are sparsely populated, geographically isolated, sometimes materially impoverished, and susceptible to health and substance abuse problems is not news. The destruction created by Hurricane Helene, however, is illuminating a resourcefulness that has always been there but hasn’t been needed to this degree for generations.

That recovery has had to begin with regaining access to places and people still mucking themselves out of the mud and debris. The September 27 flooding severed the two main arteries connecting Tennessee to North Carolina. Interstate 40, which curls through the mountains between Knoxville and Asheville, closed that day when parts of it crumbled away. Farther north, the same thing happened to I-26, which runs from the highlands in northeast Tennessee to Asheville. Hundreds of smaller thoroughfares remain closed. After Helene’s historic floods destroyed interstate and country road alike, individual cities and communities were cut off from each other. Asheville, a city of nearly 100,000 people, was completely isolated for several days because of roads and bridges being gone or underwater.

The hollers and coves in the mountains were even more isolated—and some still are. What became most important in those situations were neighbors helping neighbors.

Back in October, even before he became Trump’s omnipresent sidekick and earned an unofficial spot in his administration as chair of the Department of Government Efficiency, Nick Catoggio noticed something important about Elon Musk. And after Musk effectively tanked a stopgap government funding bill with dozens upon dozens of tweets, some of which were outright false, this edition of Boiling Frogs looks downright prescient.

Elon has also allowed anti-elitism to trump more important civic concerns, like separating truth from fiction. (Yes, the world’s richest man is somehow anti-elite.) One of his first innovations upon taking over Twitter was allowing paid subscribers to acquire the same checkmark for their account that formerly was reserved for influential users whose identities were verified. By democratizing that status, he made it harder to tell at a glance which users were trustworthy and which were not. Which makes sense: To populists, the quality of information depends on how good it makes you feel, not the method with which it was obtained.

There’s also an intense narcissistic strain in Musk’s interest in the platform. “If I had to summarize the intent of [Twitter’s] algorithm at this point, it would be twofold,” podcaster Sam Harris said recently. “The first is to make Elon even more famous than he is. And the second is to make every white user of the platform more racist.” We’ll get to that second point later, but the imperative to boost Musk’s reach online is so overweening inside the company that Twitter engineers received an emergency middle-of-the-night text last year when one of Elon’s tweets during the Super Bowl didn’t get as much engagement as he would have liked.

Narcissists’ attraction to populism is a subject worth a newsletter (or a dozen newsletters) in its own right. A conspiratorial mindset is inherently a narcissistic mindset since it assumes the subject is possessed of insight that the average sheeplike mortal lacks, and populism is rancid with conspiratorial thinking. It’s not a coincidence that the two most influential figures in modern populism, Donald Trump and Elon Musk, are also two of the most obnoxious narcissists in global public life—and each the owner of his own social media platform, which isn’t a coincidence either.

Given that Donald Trump claimed he won the 2020 election when he didn’t, it’s perhaps unsurprising that he and other Republicans might read too much into his actual victory in 2024. Yuval Levin, the the director of social, cultural, and constitutional studies at the American Enterprise Institute and a brilliant writer on the topic of our institutions, explained that, while Trump is not the first to overread his mandate, his victory does say something about the state of the electorate.

This is the trap that our 21st-century presidents have tended to fall into. They win elections because their opponents were unpopular, and then—imagining the public has endorsed their party activists’ agenda—they use the power of their office to make themselves unpopular. This is why the public moved left on key issues during Trump’s first term and right during Biden’s. Voters in this election rejected the excesses and failures of the left far more than they endorsed the right—or much of anything else.

It would therefore also be a mistake to imagine that this election victory is an endorsement of Donald Trump’s character and behavior. In the exit polls, just 43 percent of the electorate said Trump has the moral character to be president. Fifteen percent of his own voters said he didn’t. And 67 percent of voters blamed him for the violence at the Capitol after the last election.

That Trump was elected despite this widespread perception of his low character is surely an indication of one thing his victory does portend: The Trump era has lowered our expectations of the presidency. Our standards for the behavior of public officials have fallen to a degree that will exact a cost for many years to come.

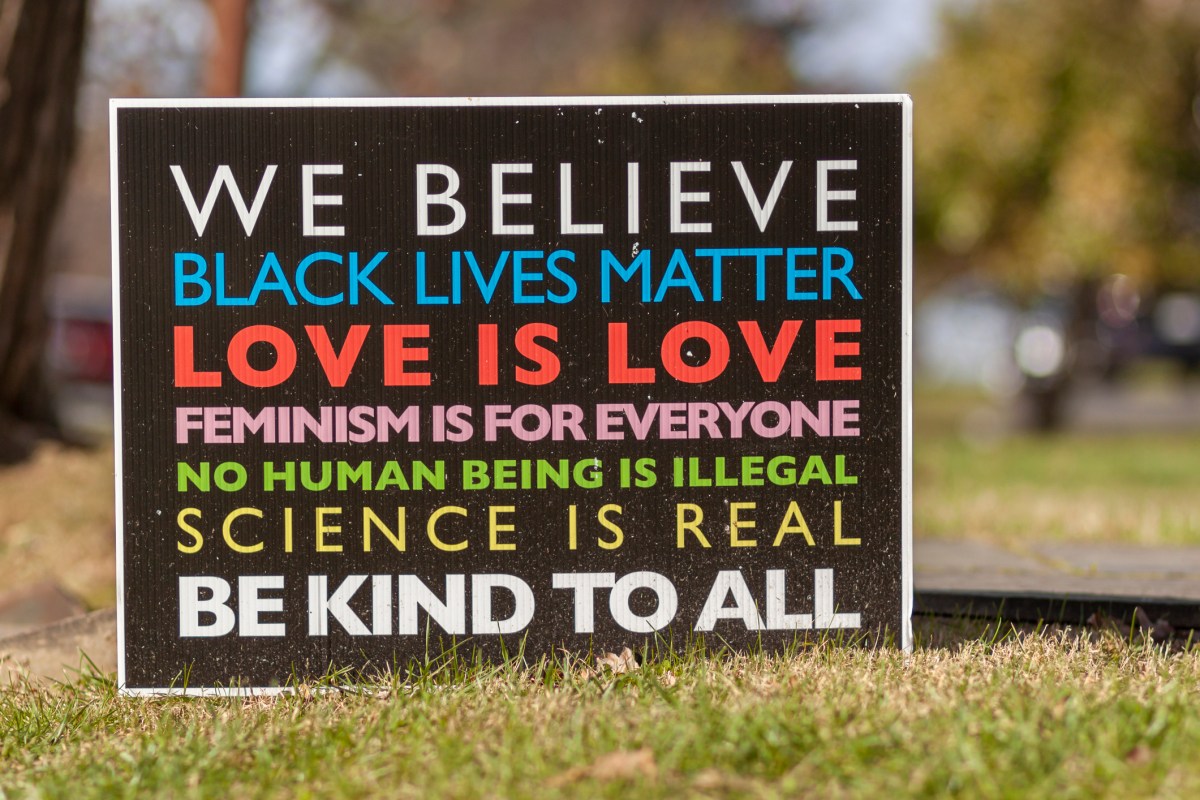

There was a lot working against the Democrats in the 2024 election—Biden’s age, the late switch to Kamala Harris, the economy that didn’t feel quite as strong as they insisted—but the wokeness didn’t help. Yascha Mounk, the founding editor of Persuasion, is worried that Democrats will ignore this very obvious takeaway from their defeat.

Many parts of the party are in outright denial about the extent to which what [James] Carville has aptly named “faculty lounge politics” is harmful to its electoral prospects. Jon Stewart, who for all of his affected irreverence is usually a reliable spokesperson for the Democratic mainstream, summarized the emerging consensus on his show last week. Kamala Harris, he claimed, did not run on identity politics, and so identity politics was not responsible for her defeat. “They didn’t do the woke thing,” Stewart quipped. “They acted like Republicans for the last four months.” Some progressive journalists with big platforms were even more dismissive. According to one, the election was decided not by the hope for “a better life for your family and future for your community,” but rather by a widespread “desire to dominate and inflict cruelty on outgroups.”

Moreover, each of the party’s fractious wings is insisting that Harris lost because she did not follow its preferred policies and political style. Sen. Bernie Sanders and his allies have been blaming the defeat on the unwillingness of Democrats to fight for more economically progressive policies. Meanwhile, other wings of the party have blamed the defeat on the fact that Democrats were insufficiently radical on cultural issues or did not change course on the conflict in the Middle East. Nearly all senior Democrats believe that the party should change; it just so happens that most of them think it should come to agree with what they have said all along.

Steve Bannon got out of prison—where he served a four-month sentence for ignoring a subpoena from the January 6 committee—about a week before the 2024 election and immediately hit the campaign trail for Trump. While Bannon served briefly in the first Trump administration as the president’s strategist, the still-influential right-wing bombthrower will be guiding the MAGA movement from the outside this time around. Michael Warren sat down with him in November to get a sneak preview.

From Bannon’s basement, the War Room and the organized MAGA movement are working hard to shape the second Trump administration in their image—“assisting the transition” is how he puts it. That means pushing back on insufficiently populist picks before they’re made. It means rallying around selections like Robert F. Kennedy Jr. for health and human services secretary and Tulsi Gabbard for director of national intelligence. It also means publicly shaming Republicans who appear to be deviating from the Trump line on these nominations. (“Folks in Utah, you’ve got a prooooblem,” he said on his show of John Curtis, the newly elected Republican senator whom Bannon calls a “Romney clone” and suspected of being a hard “no” on [Matt] Gaetz.)

Perhaps as important as the personnel selections themselves is the perception of who has the power in the new Washington. The Gaetz fiasco was a stark reminder to Bannon that Trump’s successful 2024 campaign is just the beginning, not the end, of his project. And of all the forces being marshaled against them, the institution standing most in Bannon’s way—which is, he would insist, Trump’s way—is the Republican Senate.

Back in the spring, British pediatrician Hilary Cass published her findings from a yearslong research project looking into the National Health Service’s policies regarding gender-transition treatment for youth. She found that it “is an area of remarkably weak evidence, and yet results of studies are exaggerated or misrepresented by people on all sides of the debate to support their viewpoint.” The Cass Review prompted restrictions on puberty blockers and hormones for young people in the U.K., mirroring restrictions in other European countries. But her report caused a firestorm in the United States. Jesse Singal analyzed both the report itself and the American reaction to it.

Youth gender medicine is far from the only subject that has turned into a toxic circus since 2016 or so, but I do believe it’s an outlier. With a few laudable exceptions, the way that left-of-center media outlets, academic institutions, politicians, and medical and mental-health authorities have handled this issue has been a case study of how ideology and negative polarization can not only corrupt science and its communication, but also melt it down into a rank molten sludge.

A few different things happened at once. First, Donald Trump had his usual deranging effect on everyone, and journalism was hit particularly hard. As former New York Times editorial page editor James Bennet and many, many other disillusioned journalists have argued, this—alongside the post-George-Floyd racial reckoning—caused some journalists to see themselves more as activists fighting for a better world than as dispassionate chroniclers and analysts of that world.

To be sure, the industry had already become more populated with activist-minded writers and editors over the last decade-plus. Trump’s rise and the racial protests of 2020, however, prompted a new streak of moral certitude—and at the worst possible time. Journalism was already contracting under the weight of unsolvable structural problems with its business model. Faced with layoffs, outlets’ most expensive employees were often among the first to be let go. On the science-writing front, those are the sorts of journalists—savvy, experienced reporters with decades of expertise and old-school training—best qualified to wade into a fraught area with the appropriate mix of compassion and skepticism, to know how to read a study or at least who to call to have it explained to them. But they’re now almost extinct.

Righties who put aside their concerns about Trump’s character and voted for him in 2016 in the hopes that he’d install conservative judges got what they wished: three Supreme Court justices and the end of Roe v. Wade. But at what cost? Gregg T. Nunziata, executive director of the Society for the Rule of Law, explained.

Ominously, there are signs that the illiberalism of the Trump era has begun to infect how some legal conservatives think about their core commitments to the role of the courts. Partisans promise that Trump in a second term would nominate judges more loyal to the president while Trump-friendly, post-liberal thinkers develop theories like “common-good constitutionalism” in which conservative judges would abandon originalism in favor of promoting certain ends. Adrian Vermeule, the leading academic proponent of the latter view, has argued that “originalism has now outlived its utility, and has become an obstacle to the development of a robust, substantively conservative approach to constitutional law and interpretation.” It would be deeply ironic, and the ultimate failure of the movement, if the “but judges” bargain were to end with purportedly “conservative” judges legislating from the bench.

The Founders knew that the best judges could not guarantee American liberty and preserve self-government. They considered the judiciary the least powerful, and least dangerous, branch. They put their faith, instead, in the checks and balances of the structural Constitution; they believed a self-respecting Congress would resist an overreaching executive and ambition would “counteract ambition.” Ultimately, they rested their hopes in the American people to demand this of their leaders. Washington, in his farewell address, wrote: “It is important, likewise, that the habits of thinking in a free country should inspire caution in those entrusted with its administration, to confine themselves within their respective constitutional spheres, avoiding in the exercise of the powers of one department to encroach upon another.”

The experience of the Trump years has badly damaged these bulwarks of American liberty. Congress stands disarmed, by choice, before an ever-overreaching executive. The American people, poorly grounded in civics and frustrated by politics, do not expect a commitment to constitutionalism from their leaders. Many demand the opposite. Voters now have less faith in their government institutions and neutral proceedings, more animosity toward the opposing party, and a deepening desire that elected representatives “fight,” not legislate.

This one was a doozy. As the presidential campaign heated up over the summer, left-wing activists began to claim that the Heritage Foundation’s “Project 2025” roadmap called for banning contraceptives and IVF, ending school lunch programs, cutting Social Security and Medicare, and a whole bunch of other things that it just didn’t do. A few of the allegations were true: It did, for example, recommend eliminating the Department of Education. But fact-checker Alex Demas spent three days combing through the 900-plus pages of the document, double- and triple-checking. The result was the most exhaustive fact check we’ve ever published (and the one for which we received the most hate mail!).

Defund the FBI and Homeland Security: False

There are no calls to defund the FBI or Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in the plan. In his chapter on the DHS, Ken Cuccinelli recommends that the department be broken up and integrated into other departments, but he does not argue that the department should be otherwise defunded. “Our primary recommendation is that the President pursue legislation to dismantle the [DHS]. … Breaking up the department along its mission lines would facilitate mission focus and provide opportunities to reduce overhead and achieve more limited government.” The plan also includes several FBI reforms centered on “restoring the FBI’s integrity,” but none mention a decrease in funding.

Use the military to break up domestic protests: False

The plan does not call for military intervention in domestic protests or demonstrations. The U.S. military is restricted in most circumstances from engaging in civil law enforcement by the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878. In November, the Washington Post reported that Project 2025 was developing draft executive orders that would use the Insurrection Act to allow for domestic military deployment, but those draft orders, if they do exist, are not part of the project’s Mandate for Leadership or otherwise publicly known.

Mass deportation of immigrants and incarceration in ‘camps’: Partly false

Camps for unauthorized immigrants and mass deportations are not mentioned in the plan, but detentions and deportations would likely increase under the plan’s stricter border security measures. Cuccinelli writes in his chapter on the DHS that “Prioritizing border security and immigration enforcement, including detention and deportation, is critical if we are to regain control of the border, repair the historic damage done by the Biden Administration, return to a lawful and orderly immigration system, and protect the homeland from terrorism and public safety threats.”

If you’ve read our coverage of the evangelical leaders’ capitulation to Donald Trump over the years, you might have expected a book titled Shepherds for Sale to be an exploration of that topic. Instead, author Megan Basham argues that the real problem is that too many evangelicals have sold out to the left. Warren Cole Smith, who knows many of the people Basham criticized in the book, noted in this scathing review that much of her work appears not to have been rigorously fact-checked before getting to the real problem with the book.

The real sin of those demonized by Basham is their public opposition to Trump. Her book purports to fight for the Gospel against heretics, but Basham is waging a proxy war, defending Trump against his evangelical critics, whom she labels the “elite evangelical figures who had proudly worn the ‘Never Trump’ moniker.”

Basham is correct when she writes that journalism can be part of the solution to problems in the church and the culture generally. Courageous, fact-based journalism could move the needle on some of the vexing problems of our time, including immigration and climate change, two issues Basham tackles in Shepherds for Sale. She is also right that the large institutions of the Evangelical Industrial Complex do not have the ability or the willingness to police themselves. As I have written elsewhere, “journalism can save the evangelical movement.”

But Shepherds For Sale is not journalism—it is propaganda. It is not part of the solution, but part of the problem.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.