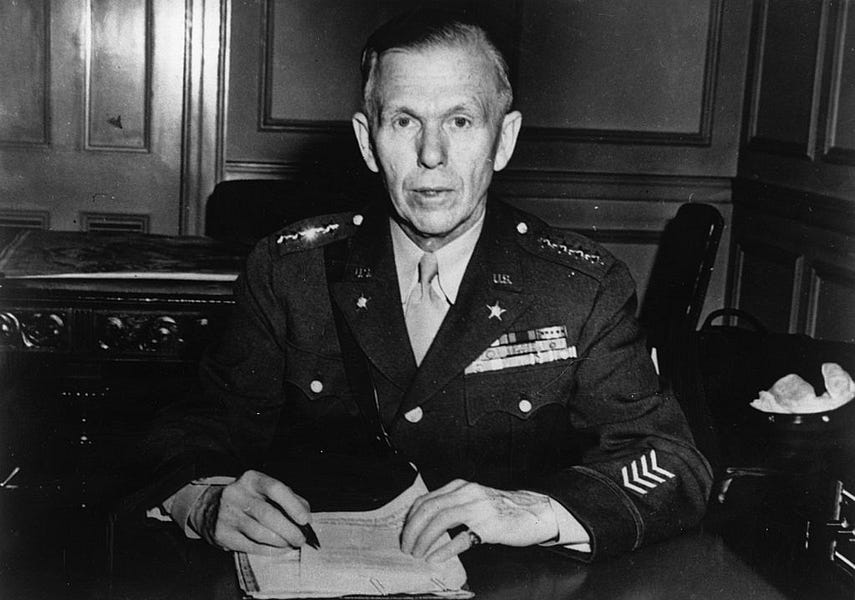

On June 5, 1947, then-Secretary of State George Marshall delivered Harvard University’s commencement speech and used the opportunity to outline the ideas behind the foreign aid program that would help Western Europe recover from World War II and come to bear his name.

Now, 75 years later, when an updated version of the Marshall Plan is being widely called for as a guide to how the United States and its allies should respond to the Ukraine crisis, the Marshall Plan and its origins deserve our renewed attention.

America had come to the aid of other countries before, of course. It contributed to Belgian relief in World War I, and through the Lend-Lease Act of 1941 provided Great Britain with military aid before we entered World War II. But the Marshall Plan was different in scale and intent from these earlier ventures. It was designed to get Europe back on its feet with sustained help, much as the New Deal was designed to help America recover from the Great Depression.

Marshall’s Harvard speech took him just 12 minutes to read, but in it he made the urgency of the moment clear. “I need not tell you the world situation is very serious,” Marshall began by saying. America could not afford to watch events from the sidelines. What happened in Europe had consequences for us if we wanted to live in a world in which there was “political stability.”

The good news, Marshall declared, was that America was positioned to help Europe if we faced up to “the vast responsibilities which history has placed on our country.” We had emerged from World War II with our factories and farms intact. We could afford to help. We needed only to make sure we acted collaboratively. It was important for us, Marshall insisted, not “to draw up unilaterally a program designed to place Europe on its feet economically.”

“It was like a lifeline to sinking men,” Ernest Bevin, Britain’s foreign secretary, declared after hearing Marshall’s speech. “It seemed to bring hope where there was none.” The next day Bevin reached out to French Foreign Minister Georges Bidault to begin the diplomatic process that would bring together the 16 nations that would be beneficiaries of the Marshall Plan.

Neither Bevin nor Bidault could be sure of the Soviet Union’s reaction to Marshall’s speech. But it was easy to guess. Given his own problems, Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin was only too happy to see Western Europe in economic chaos.

Stalin was right to worry about the damage the Marshall Plan could do to his Cold War ambitions. The Marshall Plan strengthened Western Europe and undercut the strength of Communist Parties in France and Italy. Although Marshall Plan aid averaged just 2.5 percent of the combined national income of the Marshall Plan countries, it worked as a pump primer. It gave those nations a chance to rebuild without cutting back their social welfare programs.

Equally important, the Marshall Plan encouraged cooperation among countries that had traditionally viewed each other as rivals. NATO was an outgrowth of the Marshall Plan. So was the European Payments Union, which allowed the nations of Western Europe to trade with each other, and so was the European Coal and Steel Community, which brought France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxemburg into a joint industrial agreement.

In 1948, the Soviets wanted to see Germany kept weak and forced to make reparations. The Soviets would push the West to the brink of war by cutting off rail and road traffic to West Berlin, which was in the Russian zone of postwar Germany. The Berlin Airlift, which brought food and fuel to West Berlin, would prevent a potential shooting war, and in 1949, Stalin, seeing that his Berlin blockade was failing, ended it. He had to content himself with keeping the Eastern European satellite nations that he controlled from joining the Marshall Plan.

Today, the combined military and economic response of America and the West to Russia’s assault on Ukraine has produced many of the same unifying results that the Marshall Plan did. The decisions of Finland and Sweden to apply for NATO membership reflect the growing awareness in Europe that Russia seems undeterred by international norms from invading smaller neighboring countries.

All this is good news, but it does not mean, as historian Adam Tooze warned in The New Statesman, that the West’s economic resources are going to be equal to Ukraine’s vast needs.

In addition it remains unclear what it will take for Vladimir Putin to stop his assault on Ukraine. It is hard to imagine him ending his war in Ukraine without some face-saving concessions that enable him to claim he was justified in his invasion. With his nuclear arsenal, Putin has a stronger hand to play than Stalin did in the 1940s. Not until August 1949 did the Soviet Union first test an atomic bomb of its own.

Because Putin controls the news and has silenced most of his opposition in Russia, he may be able to continue a war that has hurt Russia’s economy and damaged its military for a long time. To stop the current siege of Ukraine, America and the West are going to have to take steps that in all likelihood involve compromises the Marshall Planners were able to avoid because of America’s post-World War II military strength.

On its 75th anniversary the Marshall Plan should give us hope that we are on the right track with regard to Ukraine but not encourage us to think we can simply get history to repeat itself.

Nicolaus Mills is professor of American literature at Sarah Lawrence College and author of Winning the Peace: The Marshall Plan and America’s Coming of Age as a Superpower.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.