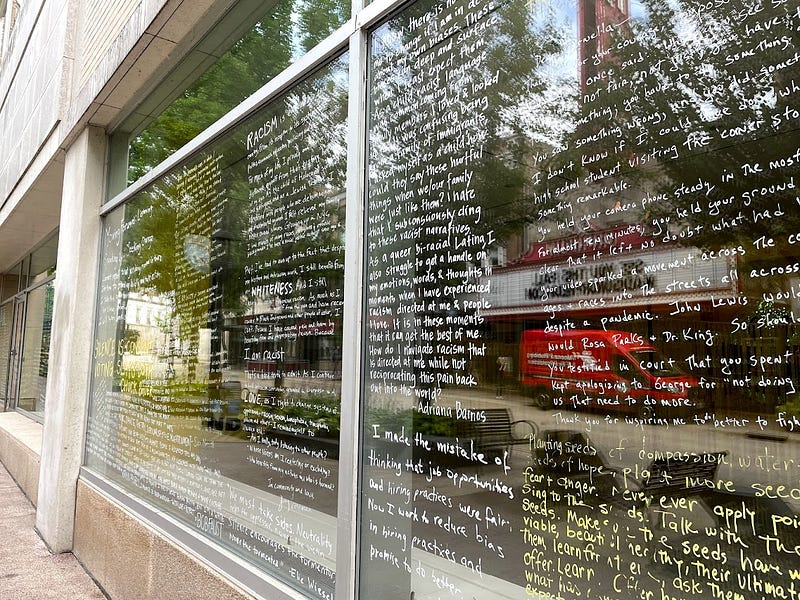

The giant glass window at the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, boarded up for nearly a year, is now covered with scribblings from local white people confessing their guilt.

“As a Jewish lesbian,” wrote one participant, “I identified with people who are dehumanized and discriminated against. I felt relieved my family never owned slaves. … I’ve been a social justice activist since age 6.”

“But I’ve had to own up to the fact that despite my history and antiracism work,” she continued, “I still benefit from my WHITENESS. … I have caused pain and harm by benefiting and perpetuating racism. Because I am a racist.”

The art installation, which invited local leaders to write “letters to the world toward the eradication of racism,” came a year after the Wisconsin city grappled with violence and looting over the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police. Night after night, groups of protesters marched through city streets, smashing windows, tearing down statues of abolitionists, and burning dumpsters, as police officers largely stayed out of the way.

The protests and the pandemic were a double whammy for Madison’s vibrant downtown. A year later, stores up and down State Street—the busy corridor between the State Capitol and the University of Wisconsin-Madison—remained boarded up, covered in graffiti-style artwork painted by local activists.

Some of the mom-and-pop shops never recovered—according to downtown Madison’s Business Improvement District, 36 businesses have closed permanently and 17 more remain closed temporarily.

In some cases, the glass windows have been repaired. But instead of being boarded over, they are home to “Property for Rent” signs. According to the BID, as of March, there were 47 vacant addresses in the area.

“Unfortunately, the damage by the hooligans and the lockdown to combat the pandemic has been done,” said Bill Connors, executive director of Smart Growth Madison, a local real estate group.

“As you walk down State Street today, you see many empty commercial spaces,” Connors told The Dispatch. “It will take years to find business tenants to fill all of those spaces. It took decades of effort and investment to change Downtown Madison from a ghost town after 5 p.m. to a vibrant destination, and now it feels like the rock has rolled down the hill and we need to push it up the hill again.”

“The emotional challenges they have and are continuing to undergo is indescribable,” BID executive director Tiffany Kenney told the Wisconsin State Journal in March.

But while it would make sense for the city to come to the aid of business owners who were harmed through no fault of their own, city leaders withheld aid from State Street, saying it would be “institutional racism” to help rebuild an area with so few black-owned businesses.

One local business owner who asked not to be identified for fear of retribution by the city told The Dispatch government leaders have not done enough to help local businesses, and that many are owned by women and minorities.

“What’s lost on a lot of people is the number of women and minority owned stores that were on State Street,” they said, arguing the city council didn’t consider business owners from Asian or Middle Eastern countries “minorities.”

“There was a very strong contingency of [city leaders] saying, ‘people of color are not black people,’ and ‘black people are being completely left out of this city,’” the business owner said.

The owner noted in July of last year, the Madison City Council rejected a $250,000 aid package to State Street businesses damaged by the riots because the package ostensibly didn’t do enough to help black business owners.

At the time, Alderwoman Rebecca Kemble objected to the package, calling the State Street area “the whitest neighborhood in the city.”

“This is quite literally institutional racism,” Kemble said of giving State Street businesses money to help rebuild.

Instead, in September—after most businesses had been boarded up for months—the city council passed a black business-centered $750,000 “Small Business Equity and Recovery Program” to “create a path toward equitable success, especially within the black community, by providing tools and resources for entrepreneurs to prepare for a post-pandemic struggling economy.”

The package included a much smaller “downtown recovery plan” that provided loans of up to $12,000 for businesses that suffered “extraordinary losses” in 2020.

But for some, this package was far too little, too late.

“The city government could have provided financial assistance to State Street and Downtown businesses to help them weather this storm, but a group of alders on the Madison Common Council used equity as a pretext to deny assistance to businesses,” Connors said. “This was extremely unfortunate. I think there is widespread belief among owners of the remaining State Street and Downtown businesses that the city government does not care about them.”

The biggest project currently roiling State Street businesses is a city plan to add two 60-foot long “rapid transit” bus stations to the street, which business owners say would block the visibility of their stores.

“It’s going to hurt us big time,” Abdul Lababidi, owner of the Princess of India store, told a local paper. “It’s like they’re telling us, we don’t want you here,” said Lababidi, whose store was looted during the protests.

But the city’s progressive elected officials see the business closings as an opportunity to remake Madison as—in today’s parlance—an “anti-racist” institution, prioritizing racial equity and social justice. Transforming the city into an engine for “racial healing” has dominated policy in the post-riot area.

“We’ve heard countless experiences from communities of color about how the Downtown, including how businesses and neighborhoods interact with people, is often discriminatory and hostile,” Eli Judge, president of Capitol Neighborhoods Inc., told the State Journal. “You hear stories of people discouraging Downtown nightlife spots from playing certain kinds of music and serving particular types of alcohol because it might attract an ‘undesirable’ crowd.”

“We can’t go ‘back to normal’ because ‘normal’ was clearly not working for everyone,” he said.

Judge declined multiple requests by The Dispatch to comment for this story.

Businesses are taking the hint, and are boosting their anti-racist credentials to win approval for large projects. Some changes are positive—one developer who just received approval for a $125 million project near the State Capitol has dedicated an entire floor of the project to the Boys & Girls Club, including areas set aside for nonprofits and minority businesses.

Another property company is working with the city’s black and Latino chambers of commerce to bring pop-up shops to State Street’s 400 block. And the city is raising funds to erect a statue of former judge and Secretary of State Vel Phillips, the first African American to win statewide office in Wisconsin. (By comparison, the city does not host a statue of James Madison, the city’s namesake and author of the Bill of Rights.)

Other developers have taken to using “woke” terminology to earn approval for lucrative contracts.

Core Spaces, a national developer of luxury student housing, has been facing questions about how much “equitable” student housing it will be providing in a new State Street building.

According to the plan, 10 percent of the new structure’s 1,100 beds would get a 30 percent discount off the roughly $1,000 monthly rent. But Campus Area Neighborhood Association President Amol Goyal objected to the plan, saying the rent was still too much and 10 percent of the beds being “equitable” wasn’t enough.

Representatives for Core Spaces, the developer pushing the project, said they have received “feedback” that the company should not use the word “affordable” to describe the new dorms. Instead, they have opted for the social justice-approved term “equitable.”

“We’ve been told not to use affordability as a word,” Mark Goehausen, a senior development manager at Core Spaces, said in June. “We feel equitable is a good word in terms of making this product available to students who otherwise wouldn’t be able to live in something this nice or downtown. So we’ve chosen the word equitable based on feedback that we should not use the word affordable.”

In addition to remaking the business environment, Madison is also trying to reform its policing practices even as crime has gotten worse. While homicides in the city have gone down this year, shootings have increased.

The city council, however, has passed a slate of reforms aimed at limiting police action, including banning chokeholds (a technique already banned unless an officer was in serious danger), preventing the police from receiving military gear from the federal government (something the city says it rarely does), eliminating “no-knock” warrants, and including more mental health workers in the department’s budget.

The City Council also created a civilian oversight board that will allow citizens to monitor and investigate the actions of the police force.

The board will be led by a taxpayer-funded “independent police monitor” who will make between $104,000 and $140,000 annually to review police procedure. For the job, the city is seeking someone with “a commitment to racial equity and an understanding of oppression and institutional racism.”

The person will have “full and unfettered access to all police data to examine systemic patterns in police conduct, complaints, and critical incidents,” and will be able to determine the validity of complaints against police officers, issue subpoenas, and determine whether processes were followed.

Yet the city still faces harsh criticism from activists who want to see policing eliminated.

“People are no longer interested in funding the police,” Mahnker Dahnweih of the activist group Freedom Inc. told a local newspaper. “That’s not a priority for people when it comes to what makes them feel safe. They’re interested in having housing for all, having secure food for people. They’re interested in making sure our educational system is well funded.”

But Connors suggested business owners of all races would be harmed if the police aren’t there to protect their property.

“Entrepreneurs of any color will not open a business if they believe there is a significant chance that their life’s work might be destroyed in one night of violence,” he said in May.

Connors told The Dispatch that businesses’ safety concerns are not as high as they were a year ago, but that’s not necessarily because the city has done anything to alleviate their concerns.

“I think that the moderation in concerns about security has little to do with anything the city government has done to reassure businesses but rather there is a sense that it is somewhat less likely that there will be any incidents around the country that would spark mass protests,” said Connors.

There is some hope for the city’s entrepreneurs: Since the pandemic hit, the downtown area has seen more than two dozen new businesses crop up. And as the business owner who preferred not to be named noted, not every business closing was due to the riots—some of the business owners were, for instance, close to retirement, and the events of the last year may have moved those plans up.

But Connors said it will be a challenge to persuade black entrepreneurs to locate new businesses on State Street and elsewhere in the downtown because of a perception that downtown Madison is not welcoming to people of color.

“It is challenging to change perceptions,” he said. “The city government has committed resources to this objective, as well as promoting black-owned businesses throughout the city.”

He did, however, offer one optimistic note.

“It is a change of pace to see Madison city government do something that is explicitly pro-business,” he conceded.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.