For the past 18 months, America has allegedly faced a shoplifting tsunami. You’ve probably seen the videos: a wave of people, masked and hooded, flooding out of a high-end department store, clutching thousands of dollars of merchandise. From San Francisco and Los Angeles to New York City, it seems like shoplifters are getting not only more prolific, but more audacious. Retailers and law enforcement officials—not to mention conservative commentators—have been quick to claim a nationwide crisis, driven by soft-on-crime policies.

But is that really what’s going on? Writing recently in The Atlantic, columnist Amanda Mull raised some doubts. She notes that much of the evidence for the shoplifting surge comes from scary but rare anecdotes, backed up by industry statistics based on private data that the public can’t double check. Mull’s criticisms echo progressive activists, who have downplayed a story they see as a threat to criminal justice reform in big, blue cities.

What’s the truth of the matter? In short, there are holes in both sides’ stories. A closer look at the numbers suggests shoplifting fell in 2020, though it may have risen in 2021. The bigger picture, however, shows a much deeper problem: America isn’t experiencing a short-term surge in shoplifting, but a long-run wave, one that has been growing in big cities for over a decade. Addressing that issue should be a top priority for city leaders, who need to keep shopkeepers and residents on their side or risk municipal catastrophe.

What’s Wrong with Current Coverage

Videos are powerful tools of persuasion. As we see in the never-ending dispute over police killings, shocking footage of brutal deaths drives people’s impression of the scale of the problem, causing many to overestimate how common such events actually are. A similar phenomenon is at play with shoplifting: Sure, video of someone stealing thousands of dollars of merchandise in one go is shocking. But how do we know it is representative of a bigger problem?

Retailers have been quick to claim the trend is real. In coverage of a shoplifting wave in San Francisco, for example, the New York Times cited Walgreens’ claim that 17 store closures in the city were thanks to the scale of shoplifting, and the CVS crime chief who labeled San Francisco “one of the epicenters of organized retail crime” told Mull that shoplifting is up 300 percent since the beginning of the pandemic.

These claims might be true, though local reporting has cast doubt on them. The problem is that we have no way of independently assessing their validity: summary statistics, devoid of context, just don’t tell us much, especially when presented by interested parties. Firms like CVS and Walgreens could release “shrinkage” data—precise information on how much inventory each store loses to different sources, including shoplifting—but they don’t. That not only makes their claims hard to judge, but should cause us to trust them less.

There is public data about the crisis, but it can be fraught. Some stories cite estimates from the National Retail Federation, which claims based on a survey of unnamed retailers that over the course of 2020, affiliated stores lost about $700,000 to “organized retail crime” per $1 billion in sales. That’s up from $450,000 in 2015 … but essentially unchanged from every intervening year starting in 2016. In the same time period, NRF respondees say shoplifting apprehensions have fallen while the average dollar loss per incident has remained approximately unchanged. In other words, the NRF data don’t suggest a big problem.

Crime data—counts of the number of complaints of shoplifting reported to the police—are less tainted by bias, but both sides of the dispute reliably ignore or misinterpret them. Those who doubt the shoplifting crisis note that the FBI reported declining property crime rates in 2020, even as homicide and aggravated assault offenses spiked. The San Francisco-based Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, in a rebuttal to the aforementioned Times story, noted that San Francisco shoplifting rates reported by the California Department of Justice hit their lowest level on record in 2020. Believers respond that stores have learned that their complaints won’t be answered, so they don’t report the crimes.

In fact, both sides are probably not looking at the right numbers. What CJCJ did not account for is that it probably undercounted shoplifting. Data reported to the FBI (and the California DOJ) follow a “hierarchy rule” in which only the most serious offense in multiple-offense incidents is reported, thereby systematically undercounting less serious offenses like shoplifting. Raw counts of “larceny theft” or “burglary” will similarly fail to reveal the extent of shoplifting, because many crimes are lumped under those categories.

To know how big the problem is, we have to count shoplifting accurately. When we do, the story takes a turn that neither side has accounted for.

What the Data Show

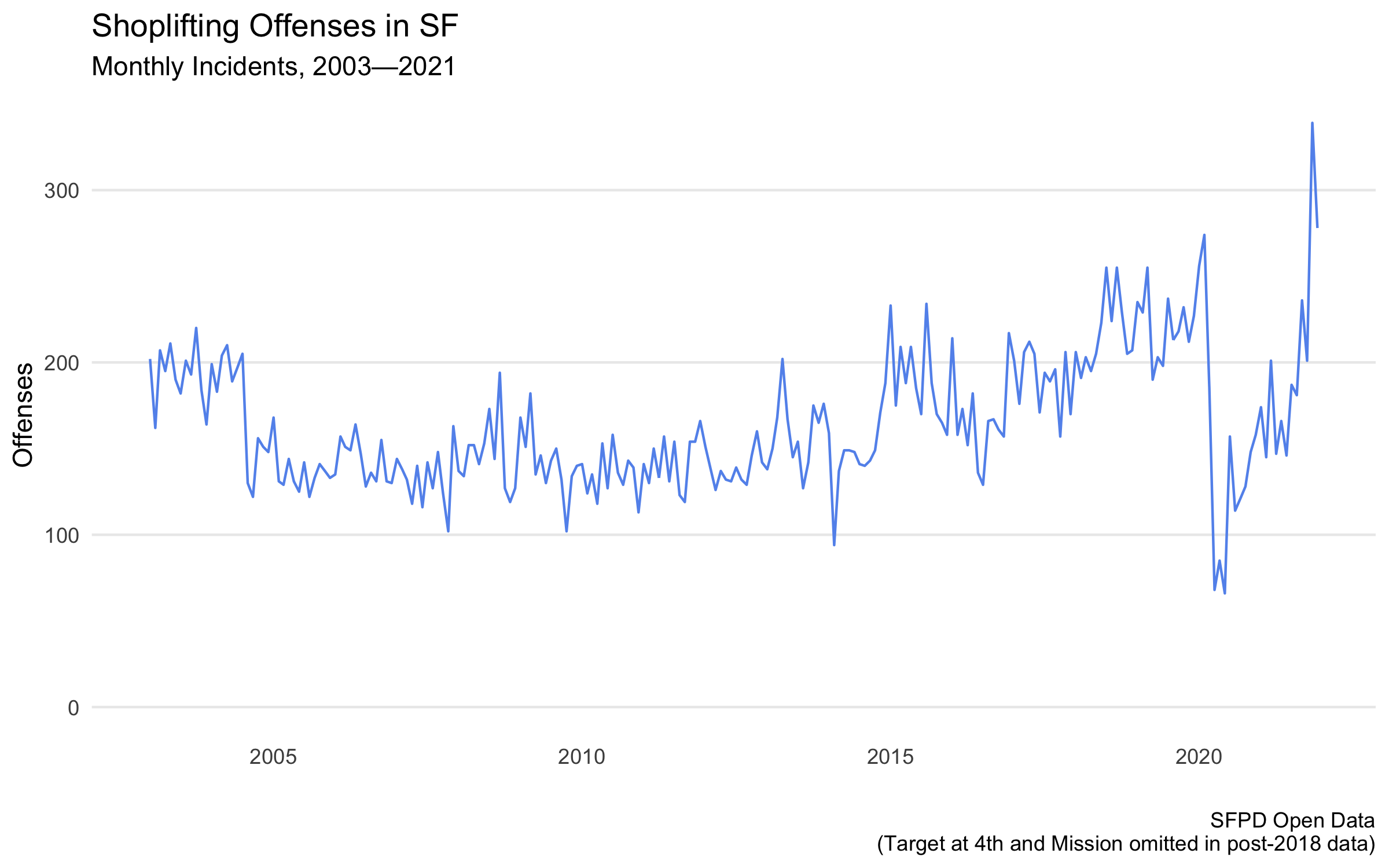

Start with San Francisco, which is often cited as the epicenter of the shoplifting crisis. The SFPD publishes data on offenses reported to it, from which we can get a count of shoplifting complaints in the city since 2003. The resultant picture shows an enormous spike in shoplifting in the fall of 2021, consonant with rising concern. But it also shows a longer-term pattern: since about 2015, the city has experienced about 200 shoplifting incidents per month, a notable increase from about 150 per month between 2005 and 2015. The one outlier is 2020, when shoplifting counts plummeted, following nationwide property crime rates.

Local reporting has noted that these data might be biased—one San Francisco Chronicle story argued that much of the recent spike is attributable to one Target that started reporting shoplifting more frequently. But even when you remove the offending store from the data, rates of shoplifting remain obviously elevated, with the exception that last fall’s spike is less pronounced. More generally, even if the recent spike is attributable to reporting bias, there is still the longer-term trend of increase in San Francisco.

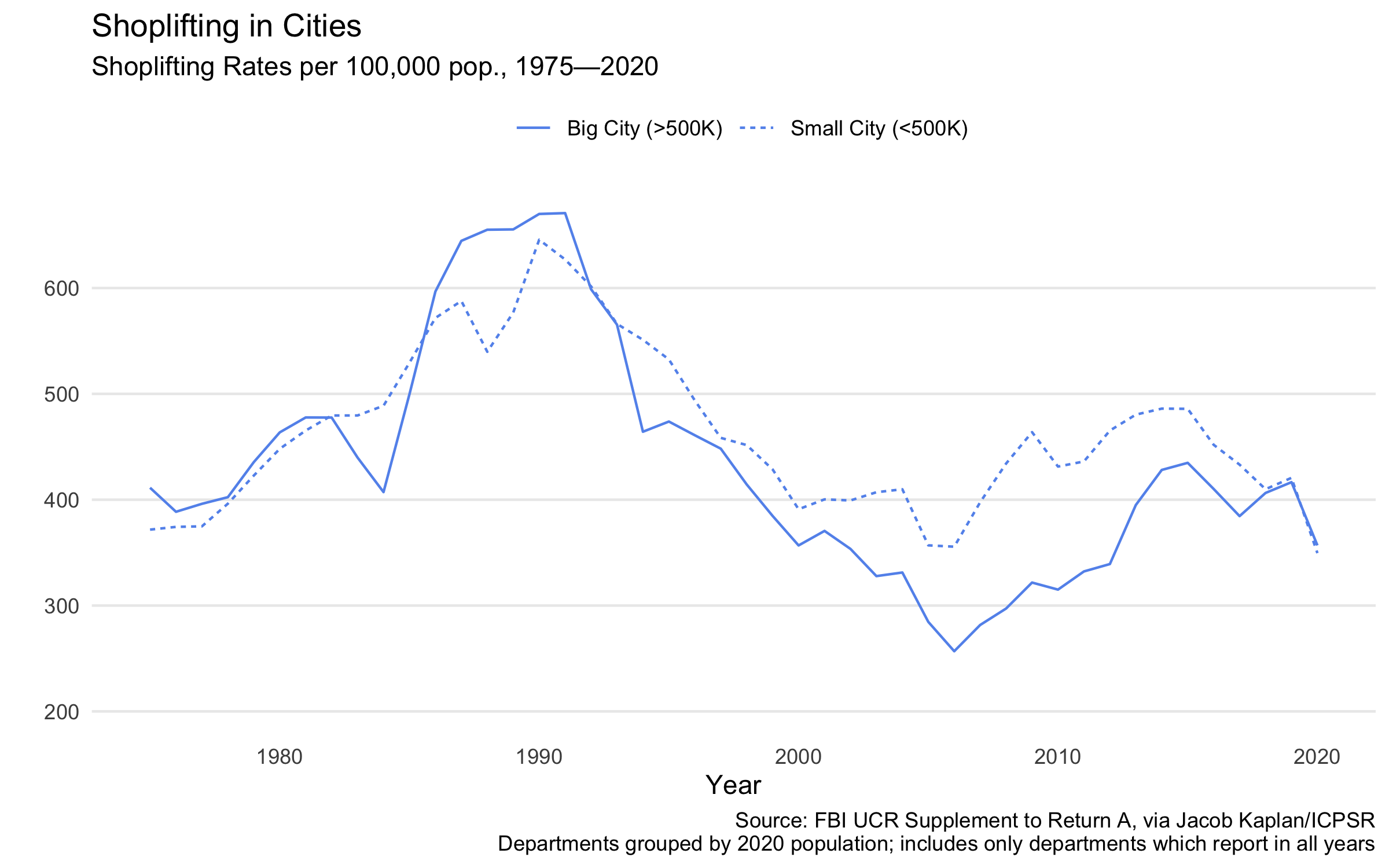

In fact, a similar trend is apparent in major cities across the country. While most coverage of the shoplifting wave has looked at trends in larceny or burglary more generally, police departments break down information about property offenses, allowing a count of shoplifting offenses. Those data show that in cities that today with more than 500,000 people, the per capita rate of shoplifting offenses peaked at 562 per 100,000 in 1990. It then fell nearly 60 percent to a low of 225 in 2006. But as of 2019, just before the pandemic, it had risen to 379 per 100,000, a 50 percent increase. A similar, albeit less dramatic, pattern obtained in smaller cities.

FBI data are subject to a variety of caveats—definitions change, departments report spottily, population estimates are sketchy. But it is fair to infer from these data, combined with the evidence from San Francisco, a general upward trend in urban shoplifting, not just over the last 18 months, but over the last decade.

What’s driving the spike? Once we see it as a long-term phenomenon, answering that question gets harder.

Why?

To be sure, there are popular explanations for the recent surge. In San Francisco, one is Proposition 47, the ballot initiative that raised from $450 to $950 the threshold amount after which a theft qualifies as a felony. On the one hand, shoplifting in the city—and in California, in the FBI data, for a year—did spike after the initiative was passed in 2014. On the other, an analysis from the Pew research center found that similar changes to the “felony theft threshold” in other states consistently yielded no change in the larceny theft rate. (I found a similar lack of pattern using the same thresholds and looking specifically at shoplifting offenses.) So there has to be more to the story than that.

Another popular target is San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin, who is facing a recall in response to his reformist agenda. Boudin has been less likely to prosecute petty theft than his predecessor, George Gascon (another progressive who is now the Los Angeles district attorney). Both men, however, prosecuted organized retail theft at similar rates. At the same time, discerning Boudin’s effect on shoplifting is complicated, because his inauguration was immediately followed by the onset of COVID, and the concurrent collapse in property crime offenses. And neither Boudin nor Gascon alone can explain the increase since 2015, given that the latter was inaugurated as DA in 2010.

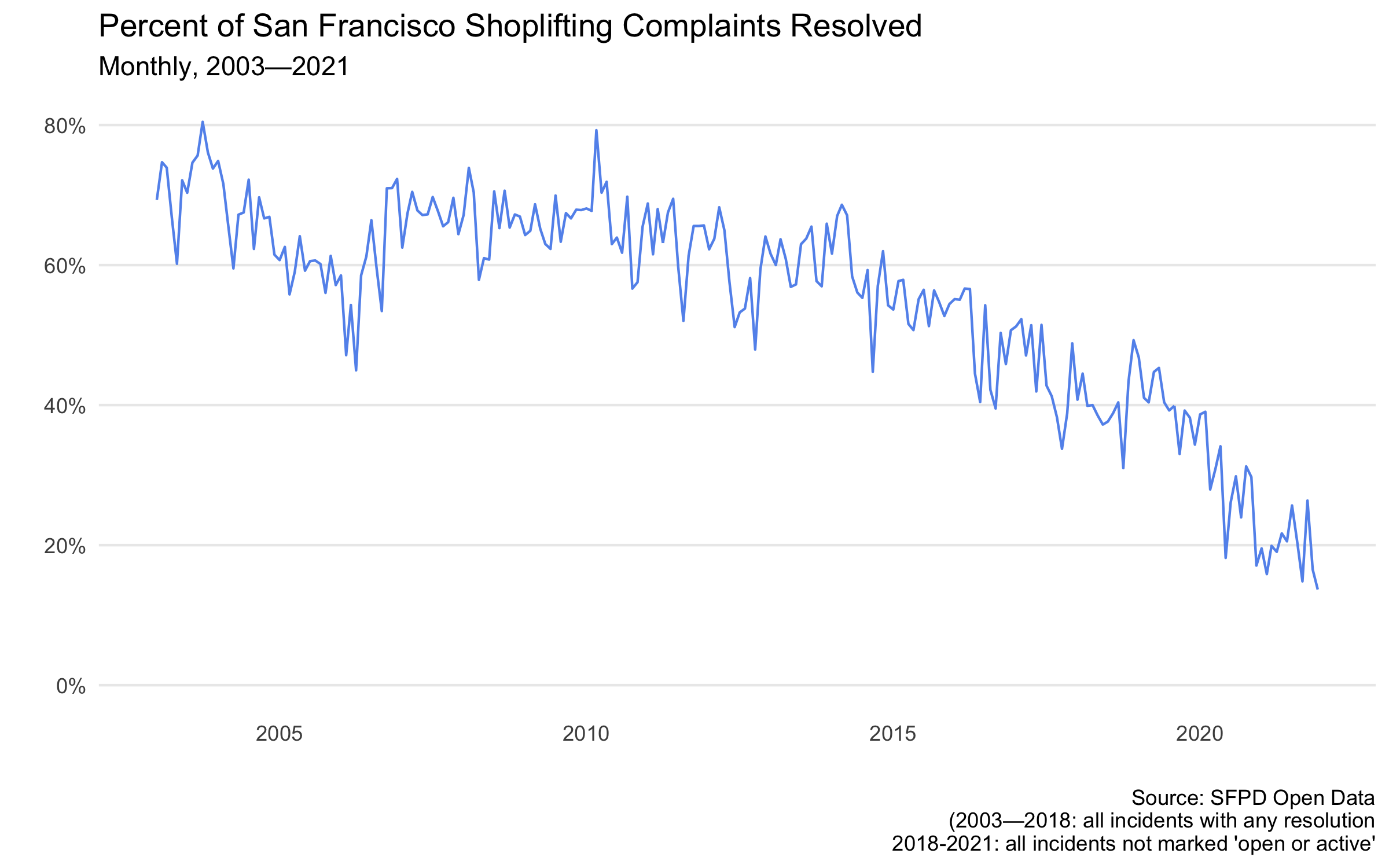

One explanation that fits these two theories together is that raising the felony theft threshold and a general reduction in willingness to prosecute led to a police pullback, where cops stopped pursuing shoplifting cases because they believed they would go nowhere. Indeed, San Francisco’s data shows a general decline in resolutions of shoplifting cases starting in 2015. (Some of that is attributable to the fact that more recent cases are more likely to be still open, but a shoplifting case from 2016 is effectively “cold” today). At the same time, this evidence could point the finger of blame at SFPD as much as the DA or state legislature; it’s hard to tell.

Policy in San Francisco doesn’t explain the nationwide increase in urban shoplifting, and there the data are even less helpful. Some of the surge is likely thanks to the Great Recession: Recessions are usually associated with upticks in property crime, though not violent crime. And while it’s hard to pin the blame on any one policy, there has been a general reduction in criminal justice system capacity: a decline (by at least some measures) in police employment, and a ratcheting back of prohibitions on low-level offenses in many major cities, including under the watch of “progressive prosecutors” like Boudin.

Cause, though, is less important than policy response. If the big city shoplifting rate is up 50 percent since its pre-Great Recession low, that should be a call to action for city executives. The dramatic decline in shoplifting, and most criminal offending, since the early 1990s is one of the great civic triumphs of our era. Mayors should be willing to commit law enforcement to swift and certain consequences for serious, big-ticket, or serial shoplifting offenses—if the SFPD isn’t clearing shoplifting complaints, it’s on London Breed to fix the problem. A failure to do otherwise degrades the quality of life in their city, hurting shopkeepers and residents and threatening America’s urban renaissance.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.