Let me tell you two stories about two media cycles as a way to illustrate how the traditional defenders of basic liberal principles in America have forgotten what to care about. We’ll go chronologically.

First: According to an April 23, 2020, post from the Frontiersman News from the Mat-Su Valley in Alaska, just a little northeast of Anchorage:

The Mat-Su Borough School District School Board voted 5-2 to ban 5 books from MSBSD schools:

I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

Catch-22 by Joseph Heller

The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Comments from the board reflected a sort of moral panic, according to the paper’s coverage. “They’re controversial because of words like rape and incest and sexual references and language and things that are pretty serious problems,” said one board member who voted for the removal.” Said another: “Why we would get into sexually explicit stuff is beyond me.”

This news went national. It was covered extensively by the New York Times, ABC, NBC, The Daily Beast, and CNN. A “Mat-Su valley Banned Books Challenge” was established on Facebook, with enthusiastic readers jamming a symbolic thumb in the eye of the censorious board by reading all five to make a point. The local bookstore said it got hundreds of orders. I was caught up in it; I bought Why the Caged Bird Sings, because I reflexively side with the censored against the censor. The Alaskan band Portugal. The Man pledged to buy any student in the district these books, since the school wouldn’t make them available.

The thing is though, the books weren’t really “banned” and were never going to be. They’re in the school district library. Teachers are allowed to assign them. They just were being taken off the curricula in certain elective courses. A nothingburger had been turned into a big story based on barely defensible reporting. The impression that the indie rock band and I got from the headlines and reporting was more inaccurate than true.

But even correcting for the fact that the narrative was bovine manure, I am sort of glad for the reaction. The impulse to treat books as dangerous seems worthy of scorn, and there’s a lot of good in treating them as sacred. So what the school board did remains illiterate and silly even after you learn the real facts.

It’s worth underlining that basing any book banning or censorship conversation on decisions by schools is a bad way to get into the complicated subject of why censorship sucks. The whole discussion of the First Amendment maps poorly onto legal minors, who society generally agrees have very limited civil rights. We agree, for example, they can be forced to attend schooling and that they have almost no property rights. Did you know they can’t even vote?

So the Alaskan school board issue isn’t strictly about bans, and it isn’t about the First Amendment. The board made a bad decision based on bad ideas. So, yes, The Things They Carried is violent, and I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings, an autobiography of an abusive childhood in a racist place, contains sexual and what could witlessly be called “anti-white” messaging. In each case, that’s the damn point. Kids aren’t stupid, and they won’t turn violent or racist or sexually sadistic from reading about the horror of land mines or racial slurs or rape that O’Brien and Angelou write about.

So, to recap, as recently as April 2020, the national media elevated a not-quite-accurate story about banning books—papering over the fact that the books weren’t banned—because there’s a strategically paranoid old instinct in liberal muscle memory to freak out about anything even vaguely in the shape of a book ban. This instinct is why Americans feel a natural solidarity with authors whose work is suppressed in foreign dictatorships, and why the story of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn writing on bits of toilet paper in a gulag has such appeal in the romantic American imagination.

Sometimes, reading banned stuff holds so special a place in our culture that, like with the Alaska pseudo-ban, it has to be filled with something kind of made up. It is, for example, the stock and trade of the American Library Association, which maintains a banned books list, promotes the reading of banned books, puts on a Banned Books Week each year, and yet plays fast and loose with what exactly a “banned book” is. Back in 2011, The Dispatch’s Jonah Goldberg explained in a syndicated column why “Banned Books Week is an exercise in propaganda.” He pointed out the hoopla that surrounded one school’s decision to remove one book from its shelves.

The preferred tactic of the BBWers is to highlight a stupid decision by one school somewhere in America and hype the anecdote as a trend. So when a school in Missouri recently removed Kurt Vonnegut’s “Slaughterhouse Five” from its shelves, it was immediately decried as the harbinger of a national trend. (The Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library immediately offered all the school’s students free copies of the “banned” book.)

There’s a lot of truth to this as a description of how the ALA is playing with words to paint a picture of the opposition to reading in America that’s not exactly accurate. And whether not-banning-but-removing literature like Slaughterhouse Five for its supposed indecency is a major violation of our civic tradition or a minor necessity of local governance is a judgment call that has divided people for a long time. Vonnegut himself made a lot of it.

In 1981, he wrote an “autobiographical collage” called Palm Sunday that begins sounding outright shell-shocked. Vonnegut had been a literary superstar for two decades, but what had him feeling scared in the ‘80s was that his book had been “banned” from a library, and then, worse, burned. The reason given was that the book contains a scene in which one soldier yells at another, “get out of the road, you dumb motherfucker.” It saves him from being blown apart by a Nazi tank. (As dangerous words go, this can be deemed a pretty pro-safety exclamation.)

Vonnegut wrote a letter to the man who burned his work. Vonnegut’s feelings were hurt, and he wanted to say so. He kept the letter private for seven years, but published it eventually and made a cause of himself over the incident. This comes in an opening chapter called “The First Amendment,” which is where Vonnegut thought of his own story as beginning, as it was once the mental beginning of the story of virtually all people of American letters. As Vonnegut puts it:

“It may be that the most striking thing about members of my literary generation in retrospect will be that we were allowed to say absolutely anything without fear of punishment. Our American heirs may find it incredible, as most foreigners do right now, that a nation would want to enforce as a law something which sounds more like a dream, which reads as follows:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

How could a nation with such a law raise its children in an atmosphere of decency? It couldn’t—it can’t. So the law will surely be repealed soon for the sake of the children.”

This sort of free speech near-absolutism and reverence for the spirit of the First Amendment, was never considered an especially right-wing thing. If anything, it was the opposite. Vonnegut was a lifelong lefty who wrote half-true hagiography of socialists like Eugene V. Debs, and he had a partisan agenda—though it makes more wise human sense to consider the author of “Harrison Bergeron” to be worthy of study and celebration by all lovers of literature than by one political side. As Vonnegut put it when asked if he was a radical, he said he could not be, because everything he believed he learned in seventh grade civics class in America’s public high school system.

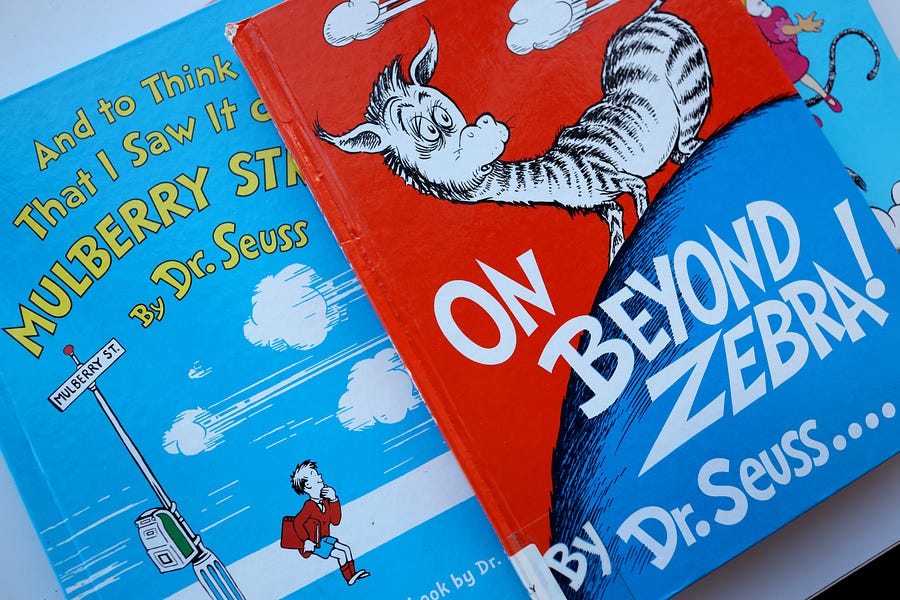

Now on, finally, to news cycle No. 2. Reports came out on Tuesday that Dr. Seuss Enterprises, which describes itself as a “company committed to care taking Theodor Seuss Geisel’s legacy,” would stop publishing six Seuss books because of “racist and insensitive imagery.”

Dr. Seuss Enterprises says it “listened and took feedback from our audiences including teachers, academics and specialists in the field as part of our review process. We then worked with a panel of experts, including educators, to review our catalog of titles.”

Well, phew. At least it was unspecified “experts,” not some yokel elected Alaskan school board.

Clearly the Seussian copyright holder has every legal right to stop publishing its own intellectual property, just as an elected school board has every legal right to take a book off a curriculum or even to stop stocking it in the library. The question is if they are doing the wise, admirable, and literary-minded thing with that right.

It’s a complicated question, and I would venture that it nonetheless has a very simple answer. Making literature and art less available and accessible to people who would wish to read or see it is bad. Children complicate this slightly, sure. Just not that much. I am open to the idea that literature does change minds. Of course it does. The reason that And Tango Makes Three, a kids’ book about gay penguin parents, is the ALA’s most “challenged” book is because it’s extremely effective propaganda for a belief I strongly endorse: Gay families should be accepted as legitimate and normal, and kids can understand this intuitively. (Some part of me also reluctantly believes it is a parent’s right to ask society not to read this book to their kids against their wishes. This, again, is why centering this conversation around children, who have fewer civil rights, is less than ideal.)

The point is, it is fine to acknowledge there are stakes to the matter of what literature is available. But the reason it’s uncivilized, illiberal, and anti-intellectual to make a book unavailable is precisely because there are stakes to what we can and can’t read. We used to defend books from moralizing censors for the same reason people want to control what kids do and don’t read: Books are tremendously important and powerful.

Every liberal once knew this, when it was Vonnegut in the docket for the crime of coarse language. Every good citizen knew that Thomas Bowdler should be immortalized as shameful in the English language itself with the world bowdlerize for effacing Shakespeare to take out all the sex and suicide and murder and swearing and cool stuff like that. And everyone understood this last April, when a small Alaskan school district deemed Maya Angelou sexually explicit and anti-white, which was absurd. Shakespeare has plays that are regularly described as sexually explicit, anti-Semitic, and anti-black, and we don’t want to ban those even though the labels actually fit. Anti-Asian stereotypes clearly appear in, among other places, Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Are we banning the sale of anything that contains racially offensive stereotypes according to an “expert” because it is damaging? Are we encouraging anyone who owns the intellectual rights to art that is offensive to take it down? If so, what does that mean for museums?

Supposedly the investigation into the problematic nature of the Seuss works is tied up in the author’s questionable moral life. Seuss famously took part in a bunch of war propaganda efforts, though it seems like trying to help defeat Hitler should not really be a strike against him. But more to the point, where exactly has this assumption come from that if an author communicates some sort of morally indecent idea in some book, then that book should go away, or stop being produced, or be kept from adults who wish to procure it? In Alaska, my question about the one book in the bunch I hadn’t read wasn’t, “But is Angelou in fact anti-white?” I don’t care whether she is or not. If she were, or if she harbored some uglier and more troubling bigotry, that would be no reason to ban her book. There’s no reason to ban any books.

Seuss’ And to Think I Saw it on Mulberry Street is now the subject of a much stricter “ban” than Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, with media concern based on much less fraudulent coverage. Yet while in April educated people and journalistic institutions knew something ugly was happening. Now, we think the unavailability of the Seuss works should leave us untroubled? Why? Am I supposed to believe that Seuss’ inclusion of the below 1937 illustration of a Chinese man is so evil and damaging as to preclude the very sale of the book it comes from in a country where I can buy the autobiography of any number of serial killers, books by Stalin, Hitler, and Mao?

What’s kind of amazing here is the difference in who is making the objection and why. We’ve reached a point at which children’s books are somehow too difficult for adults to handle. This isn’t about the books being removed from a library here and there. They will be unavailable for purchase nationally. Surely that’s a more substantive limitation of the “freedom to read” the American Library Association uses as its slogan.

Where does any of this head? The National Education Association’s Reading Across America Day, originally scheduled for Dr. Seuss’ birthday to reflect his outsized role in American children’s literature and literacy, has disassociated itself from him. It is not a good sign for the health of a critical and literary culture to find we live in too intense a moment of racial strife to Hop On Pop. The previous sentence’s silly sequence of words is an inherently absurdist punchline to me. But it’s not, I bet, to the author of the Education Week article “Is the Cat in the Hat Racist?” That article’s examination will be made only more complex by the forthcoming publication of the book Was the Cat In the Hat Black? in March.

Worse, Seuss is just one of the beloved children’s authors now being “challenged” despite the fact that generations of children have read their books without America trending ever more racist and prone to the spontaneous capture of colonies. The sacred American tradition of zealously protecting literature is not standing up to the need to push politics into every area. Thus we read that Laura Ingalls Wilder has had her name removed from a prize the ALA gives out for lifetime achievement in children’s literature after receiving complaints from offended parents, which is damn near to being the sort of thing that used to get you called a challenger of the Freedom to Read by the ALA.

It makes me outright despondent to read, in the Associated Press, that the Babar series of children’s books about French cartoon elephants is being dinged for colonialism (but not monarchism? Vive la révolucion before the Pachydermian Reaction!). Meanwhile, “Critics also have faulted the ‘Curious George’ books for their premise of a white man bringing home a monkey from Africa.”

At what point do we stop caving to people who think it is racist not to mentally associate a literal monkey with black people in one’s head, as though such a thing is a natural connection? These are people who think doorbells sound like dog whistles, who mount expeditions to discover offenses, and who are generally just outright paranoiacs about the role of race and ethnicity in ordinary communication. Their concerns need to be ignored.

Admittedly, when it comes to the availability of books, and just what a ban is, and whether every claim of a ban really is one, we’ve seen that it’s all a bit more political and complicated and motivated by bad faith than we might like to think. But people who obsessively inject race into every discussion of literature and want to adjudicate the fitness of art for consumption that way—whether it is Maya Angelou’s alleged “anti-whiteness” or preposterous projections about the kids who might pick up racist habits from The Man in the Big Yellow Hat—must be kept as far away from our books as possible.

Vonnegut’s little-L liberal impulse to overreact to book banning, despite there being no such extant threat in the United States then or now, is a good thing to have around, even if it leads to some annoying propaganda and culture warring from the likes of the ALA. These are, in the end, pro-book people, and even obnoxious pro-book people are good, because books are good. The way we treat books a little bit like puppies is somewhat absurd, but it is the symbolic opposite absurdity as book burning, and it’s maintained for that civilizing reason. Yet, clearly something has gone wrong if one of America’s great authors can now be pulled without the book-defensive cultural institutions yowling.

We as a culture should be doing two things for the sake of protecting literature. First, we should make sure to stop reacting in grandiose ways to fake threats. More importantly, we should make sure we actually react when there is a real threat. If we can’t do those things, we’ve lost the liberal tradition’s resistance to censorship just because someone, somewhere, said a cartoon chopstick was offensive.

It can’t all really be that brittle, can it?

Nicholas Clairmont is an associate editor at Arc Digital and a freelance writer based in New York.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.