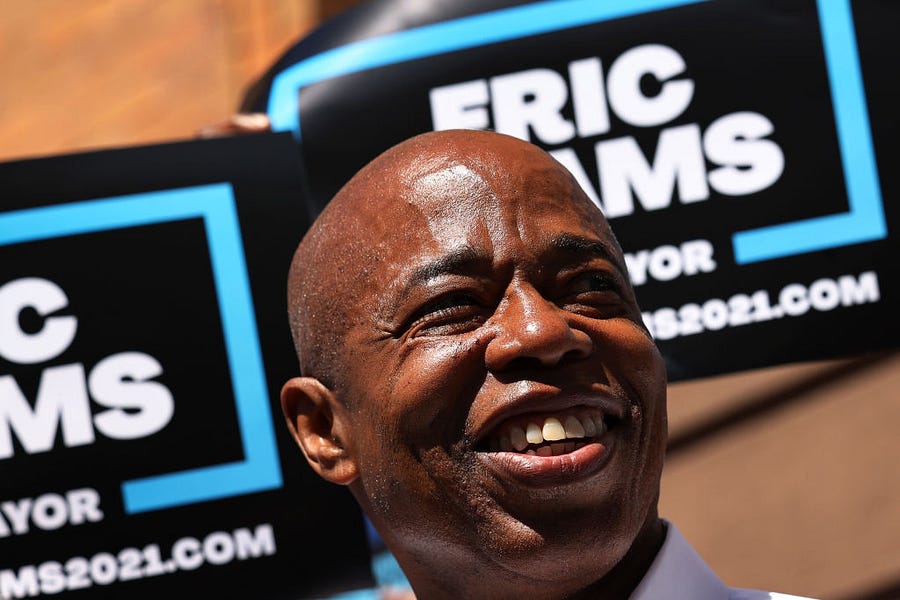

NEW YORK—Eric Adams’ campaign for mayor of New York isn’t subtle. The first thing the Brooklyn borough president and frontrunner in the race to run America’s biggest city wants you to know about him is that he’s a blue-collar New Yorker who’ll be a blue-collar mayor.

It’s the message he delivers in TV spots, when he touts his tough upbringing and 20 years on the NYPD, telling viewers: “These hands have seen rough times—and I’ve got the calluses to prove it.” And it was the message he delivered at a recent campaign event on the waterfront near the Brooklyn Bridge, where he received an impeccably blue-collar endorsement from the carpenters union.

Adams, a black, 60-year-old former cop and one-time Republican who has stuck to a moderate message in the Democratic primary race, arrived to the boisterous bars of a song called “The Champ Is Here” by Jadakiss (a bold choice). With downtown Manhattan as a backdrop and flanked by a few dozen union members in orange T-shirts, he delivered some predictable carpentry metaphors about rebuilding the city after COVID-19.

At the fringe of the press gaggle, an Adams flack said to me, “I would give you my business card, but I don’t have any. We’re a blue collar campaign.” These folks are too salt-of-the-earth for extravagances like a piece of thick paper with a telephone number on it. One especially brawny carpenter took an admirably direct approach to hammering the message home, at one point yelling simply “blue coll-ah!” in his thick New York accent.

The next thing Adams wants you to know is that he won’t defund the police. In fact, with only a few days left in the race, the simplest explanation for his status as the man to beat is the vigor with which he has campaigned on the issue of crime and public safety. He wants to bring back a plainclothes police unit disbanded last year and has called stop-and-frisk a “great tool” when “legally deployed.” He has also said he would pack heat himself if elected.

“We don’t need a mayor taking guns from police officers when we have an over-proliferation of illegal guns on our streets. I’m not jeopardizing the safety of citizens, and I’m not jeopardizing the safety of those men and women who wear a bulletproof vest,” said Adams to cheers from the carpenters.

Adams’ approach may be at odds with the prevailing message on the left today, but it would appear to be in tune with the concerns of New Yorkers. Violent crime in New York, as in other major U.S. cities, has surged since last summer, and the trend shows little sign of slowing. In the first three months of 2021, shootings were up 50 percent year over year. According to a NY1/Ipsos poll released last week, 46 percent of likely Democratic voters said they thought crime and public safety should be the top priority for the next mayor. Almost three-quarters of those respondents—again, not the electorate as a whole but Democrats—supported an increase in the number of police officers on the street.

The mayoral race won’t just determine who gets to run New York. It will also take the political temperature of urban America as it emerges from a bruising year of pandemic, lockdowns, protests, riots, and rising crime. Do the residents of America’s biggest city see 2020 as a crisis moment that provides the opportunity for radical change? Or are they more interested in regaining the ground that has been lost since last spring, rediscovering the prosperity and safe streets that they had taken for granted? In other words, if last year was “a moment,” has the moment passed?

While Adams may have a firm grip on voters’ No. 1 issue, the Democratic primary contest is far from sewn up. Now in its final stages, a crowded field, truncated campaign, and erratic polling results have made for a topsy-turvy, Wacky Races-style contest. Adding to the volatility is the introduction of ranked choice voting, a first for New York’s mayoral contest that gives a handful of candidates a path to victory.

Among them is Andrew Yang, the Asian-American 46-year-old tech bro turned political disruptor who outperformed low expectations in his presidential run last year and who spent the early months of this mayoral campaign as the frontrunner, stealing a march on his opponents (and contracting COVID-19) by pounding the pavement while most of the race was still virtual. Yang is a strange political beast. Moderate and business-friendly in many respects, he has taken a similar line to Adams on crime and earned the endorsement of the police captains’ union. But where Adams represents old-school Democratic machine politics, Yang is a genuine outsider, and parts of his policy platform, including his central promise of a universal basic income for New Yorkers, overlaps with the candidates to his left.

Then there’s Kathryn Garcia, 51, who is best understood as the Leslie Knope of the race. Her department is sanitation, which she had managed in the city for the last six years, not parks and recreation. But her message is liquid technocracy: low-key, competent, sensible public service. Armed with the endorsement of the New York Times and an unavoidable air of inoffensiveness, Garcia hopes to run the table in the ranked-choice system: few people’s first choice, perhaps, but enough people’s second, third or fourth. (A recent Manhattan Institute poll showed her doing exactly that.) To progressives, she is not the villain that both Adams and Yang have become, but like them opposes reductions in police funding and, by contemporary Democratic standards, has stuck to a centrist message.

Maya Wiley, 57, has the left lane more or less to herself after other progressive contenders ran into complications. Multiple sexual assault allegations look to have sealed the fate of serving New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer. The campaign of Dianne Morales, a 53-year-old non-profit executive, imploded in spectacular fashion last month, when the hyper-woke staff of her hyper-woke campaign abruptly unionized and went on strike, arguing that “racial aggressions, exploitation, and manipulation” were hurting “black and brown organizers” and had “created a pattern of marginalization.” And so Wiley, a scion of the civil rights movement and a lawyer who has worked for current Mayor Bill de Blasio, was duly anointed by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez as the left’s best hope.

At a recent rally in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene Park, Wiley told activists for the Working Families Party, which has emerged as a significant force on the New York left in recent years, that a return to the status quo ante would not do. In light drizzle that prompted a tortured biblical analogy about building an ark, Wiley said the city was “at a crossroads” and told a young, hipsterish crowd that “what is at stake at this election is not whether we will recover. I’m telling you, the thing we all know is that New York City recovers from every crisis … that is not the question. The question is: who recovers? … We’re not talking about going back to January 2020, because was that good enough for you?”

The Rev. Al Sharpton was satirized by Tom Wolfe as Reverend Bacon, a disingenuous Harlem rabble-rouser, way back in 1984. He’s still a player in New York politics 37 years later, and so, on the first day of early voting, Sharpton has corralled four of the mayoral hopefuls into the House of Justice, the headquarters of his National Action Network, on 145th Street.

“They ain’t here kissing a ring, they’re here to try and get elected,” says Sharpton with characteristic false modesty, in a room plastered with pictures of him meeting the great and the good. “I don’t need you to kiss the ring. In fact, I don’t want no lip prints on my ring.”

Rev. Al tells the crowd, many of whom appear to be long-serving Sharpton devotees, that he won’t be endorsing a candidate this time and will instead focus his energies on spreading the gospel of ranked-choice. Notwithstanding this newfangled method of voting, though, the Sharpton rally looks and sounds much like such events always have. It begins with Sharpton’s call and response: “No justice! No peace!” It ends with Sharpton shaking a few thousand dollars of cash out of the audience: “Give me some $50s. Play me some music.”

In between, the message is as focused on crime and prosperity as on police reform. And it is Adams whose stump speech appears to resonate the most. The ex-cop tells the mostly African-American audience a story about his mother encountering racism as a domestic worker in Queens, describes his family’s journey from poverty to the blue-collar middle class and asks that voters “don’t allow people to tell you who I am, because you know: I am of you because I became from you.”

The standing ovation Adams received in Harlem chimes with the polls. A recent Marist survey put Adams’ support among black voters at 47 percent, a whopping 32 points ahead of the next most popular candidate.

Adams’ popularity among black New Yorkers is the latest reminder of the gap between the assumptions of elite anti-racist opinion and the actual preferences of working- and middle-class African Americans. His candidacy is also a demonstration of how identity politics can be weaponized against the left to great effect. “I was beaten by police at 15, so I became a police officer to battle racism from within,” he says in one of his TV advertisements. Asked about a rent freeze in New York at one campaign stop, Adams cautioned that such a move risked “the greatest loss of wealth in black and brown and immigrant people in this city, and that’s a problem to me.”

This mayoral contest has had its bizarro moments; last week Adams found himself at the center of a strange fight about whether he meets residency requirements in New York that culminated in a teary-eyed press tour of an apartment in Bedford-Stuyvesant. But my overwhelming impression of the mayoral contest is how, well, normal it is. And in the early summer of 2021, normal is good, even exciting. COVID-19 has given fresh appeal to unremarkable, everyday stuff. And that includes the stolid, somewhat uninspiring cast of moderates who are likely to keep a progressive out of Gracie Mansion.

We were told that the pandemic would change everything. Our everyday lives would be forever transformed: we’d never shake hands or take a business trip again. Our politics would be upended, with the plague killing off outdated assumptions about what was possible. But voters’ priorities don’t appear to have changed nearly as much as AOC or Elizabeth Warren or, on a bad day, Joe Biden want you to think. If the New York campaign trail is anything to go by, the new normal looks a lot like the old normal.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.