I confess: I’m exaggerating in my title. As a professor at a small liberal arts college, of course I care—at least in a certain sense—if my students get jobs. I don’t wish unemployment upon them, and I hope they succeed in life. Someone—they themselves, their parents, their relatives, alumni who donate to a scholarship fund—is paying a lot of money so that they can get a college education, and it’s not unreasonable for them to want (as we say these days) some return on investment. Professors are reminded of this constantly: by administrators, by admission staff, by parents, by cultural polemics against navel-gazing programs of study and meaningless degrees. I get all of that. Still, whenever I am asked what my students can do with their degree, I am always sorely tempted to answer, “I don’t care if my students get jobs.”

No doubt my employers would be displeased if I succumbed to temptation and announced my indifference to a group of prospective students and their parents. Like many such colleges these days, we could use more students. Like many such colleges, we are trying desperately to discover the best strategies for attracting them. Like many such colleges, we often seem to think that the way to do this is to explain more clearly how our programs of study will prepare them for specific careers. So it is not surprising that I often find myself confronting the question: What can you do with a degree in political science, or history, or philosophy, or a related field?

Not surprising, but nevertheless a little silly. Let’s face it: If I were so good at thinking up clever and interesting things to do with a liberal arts degree, I would be doing something that paid a lot better than teaching at a small Christian college. I’m the last person you should ask what jobs your degree prepares you for. (This much, I admit, I have occasionally said to prospective students and their parents.) Teaching has its own rewards, to be sure. But you’re a lot more likely to wax eloquent about the privilege of shaping the minds, hearts, and souls of our youth when you aren’t grading their papers.

It isn’t just that I’m not terribly creative at imagining a diverse palette of exciting career options. I’m also not very interested in it. Like many of my colleagues, I’m a professor more or less because I like reading books, and being a professor lets me spend a fair amount of time doing that. (Though less than one might suppose—there are those piles of papers to grade, to say nothing of advising sessions, committee meetings, and the like.) If I were really that interested in thinking about all of the other things I could be doing, then I’d probably be doing one of them. I’m interested in plenty of things: figuring out what exactly Aristotle means in saying that each “constitution” or “regime” has its own vision of justice; whether Aeneas ultimately gives in to the forces of rage and madness that he has been holding at bay throughout Vergil’s epic; how Luther’s kingdom of God and kingdom of man should or shouldn’t interact with each other; or how the dying King Lear can help us understand just what Edmund Burke would later mean in speaking of the “moral imagination.” But different career options? Not so much.

Before you conclude that I am hard-hearted and indifferent, or perhaps simply callously self-absorbed, a qualification is in order. As someone who is perhaps not precisely a “friend” to but certainly fond of my students, someone who wishes them well and hopes that they will lead flourishing lives, of course I care if my students get jobs. I like my students, take an interest in their well-being, and hope they will find jobs that are meaningful and rewarding, jobs that allow them to do good work in the world and to support themselves and their families in relative comfort. As a fellow human being, possibly even a rather soft-hearted one, I do indeed care if my students get jobs.

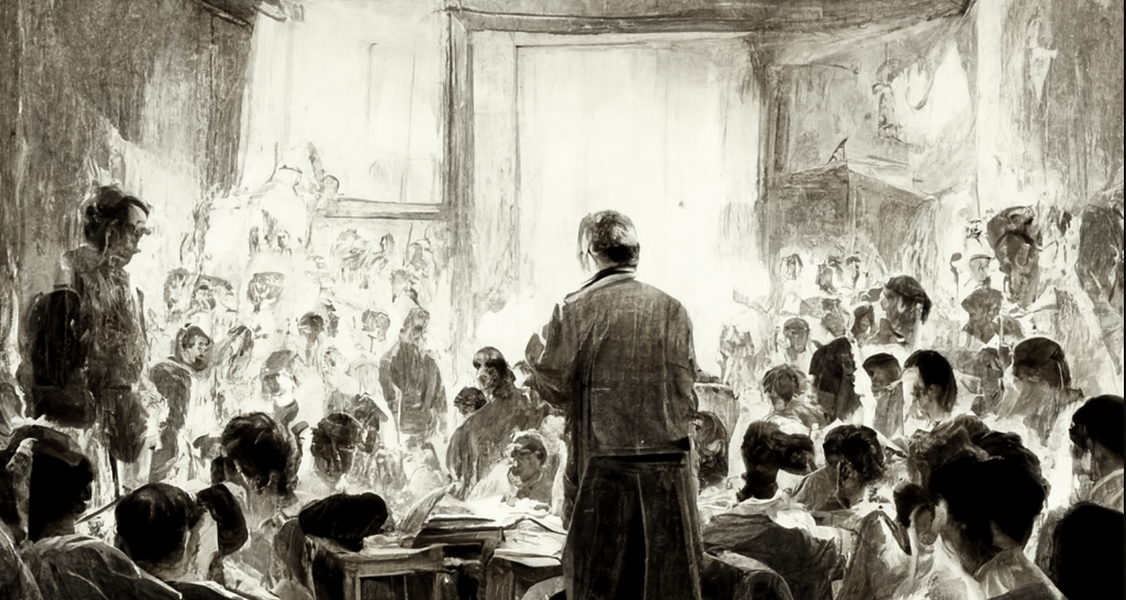

As a human being, but not as a teacher. Indeed, it is precisely as their teacher that I could not care less if they get jobs or not. When I am standing at the front of the classroom, nothing could possibly be farther from my mind than whether or not the material under discussion will help anyone in the room get a job. Earlier this week, I discussed the end of Homer’s Odyssey with a group of first-year students in a general education Humanities 101 class. If they approach it in the right spirit, the Odyssey can help students think about many questions of deep importance to their lives. Like Odysseus’ son Telemachus, they are at that awkward point of transition from adolescence to adulthood. They may be tempted to spend their time partying and having a good time rather than reading Homer and might therefore benefit from pondering Zeus’ warning at the poem’s beginning that “mortals put the blame upon us gods, for they say evils come from us, but it is they, rather, who by their own recklessness win sorrow beyond what is given.” Students are often embroiled in romantic affairs and want to know the secret of a loving and faithful relationship, and they might contemplate the model of Penelope waiting years and years for her husband to return and Odysseus struggling through so many trials to get back to her. When he finally does, they might wonder about his announcement that he will soon have to leave again for yet more journeyings and trials, asking what Homer wants to say about the conflicting human desires for exploration, travel, and discovery, on the one hand, and the longing finally to arrive at home and to be at rest, on the other. Some of them, I hope, will think back to Odysseus later in the semester when they read St. Augustine confessing to God that “our hearts are restless, Lord, until they rest in Thee.”

All of these things and more are on my mind when I lead a discussion of the Odyssey. But not whether thinking about these questions will help anyone in the room land a job eventually. I am confident that my students will not be worse off for having spent some time reflecting on such matters. Indeed, the opportunity to spend a few years as an undergraduate thinking about questions like these is a great blessing for those fortunate enough to enjoy it. It is an opportunity that Michael Oakeshott once called “the gift of an interval,” a “moment in which to taste the mystery without the necessity of at once seeking a solution.”— And that is true whether we can trace out its connection to any particular job or not.

So do I care if my students get jobs? Well, okay, sure. I care. But it would be a mistake if I spent too much time thinking about it. Or, for that matter, if they did.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.