Dear Reader (and all the ships at sea),

Joe Biden loves to say, “America is back.” He used it to announce his incoming national security team last November. “It’s a team that reflects the fact that America is back, ready to lead the world, not retreat from it.”

Last February, there were a slew of headlines about his first big foreign policy speech along the lines of this from the Associated Press:

In that speech, Biden told diplomats at the State Department, “when you speak, you speak for me. And so—so [this] is the message I want the world to hear today: America is back. America is back. Diplomacy is back at the center of our foreign policy.”

That phrase—as well as those Biden-tells-allies-America-is-back headlines—keeps coming to mind every time I read about the inexorable advance of the Taliban in Afghanistan. For the Afghans, America was “here,” and now it’s leaving. I wonder how “America is back” must sound to the people feeling abandoned by America in general, and the guy saying it in particular.

I’m not trying to pull on heart strings, so I won’t trot out the girls who will be thrown back into a kind of domestic bondage or the translators and aides who rightly fear mass executions may be heading their way. All I’ll say is that their plight does pull on my heart strings.

They’re back.

But let’s get back to this “America is back” stuff. For Biden, it seems to have two meanings. One is his narrow argument that we are rejoining all of the multilateral partnerships and alliances that Trump pulled out of or denigrated. Fair enough. I can’t say this fills me with joy, even though I disliked most of that stuff from Trump (the two obvious exceptions being getting out of the Paris Accord and the Iran deal). I think diplomacy often gets a bad rap. But I also think diplomacy is often seen as an end rather than a means. We want diplomats to accomplish things, not to get along with each other just for the sake of getting along. For too long, Democrats have cottoned to a foreign policy that says it’s better to be wrong in a big group than to be right alone.

But there’s another meaning to “America is back.” It’s an unsubtle dig at Trump and a subtle bit of liberal nostalgia all at once. It’s kind of a progressive version of “Make America Great Again.” It rests on the assumption that one group of liberal politicians speaks for the real America, and now that those politicians are back in power, the real America is back, too. But the problem is, there is no one real America. There are some 330 million Americans and they, collectively and individually, cannot be shoe-horned into a single vision regardless of what labels you yoke to the effort.

Liberals were right to point out that there was a lot of coding in “Make America Great Again.” I think they sometimes overthought what Trump meant by it, because I don’t think he put a lot of thought into it. He heard a slogan, liked the sound of it, and turned it into a rallying cry—just as he did with “America first,” “silent majority,” and “fake news.” Still, when, exactly, was America great in Trump’s vision? The consensus seems to be the 1950s, a time when a lot of good things were certainly happening, but a lot of bad things were going on that we wouldn’t want to restore.

Liberal nostalgia is a funny thing. Conservative nostalgia I understand, because I’m a conservative and I’m prone to nostalgia (even though nostalgia can be a corrupting thing, which is why Robert Nisbet called it “the rust of memory”). Conservatives tend to be nostalgic for how they think people lived. Liberals tend to be nostalgic about times when they had power.

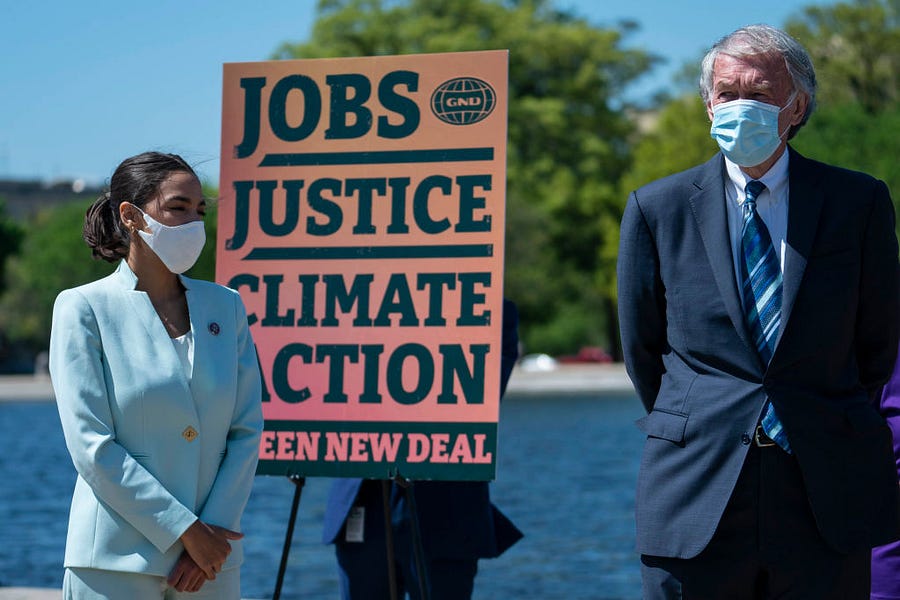

Consider the New Deal. Being nostalgic for the New Deal certainly isn’t about how people lived, not primarily. America was in a deep depression throughout the New Deal. Breadlines and men holding signs saying “will work for food” are probably the most iconic images of that time. Who wants to return to that? And yet, liberals will not banish it from their collective memory as something like the high water mark of American history. That’s why they keep pushing for new New Deals and slapping the label on new programs that consist of spending money we don’t have.

The only thing that competes with the New Deal in the liberal imagination is the 1960s in general and the civil rights movement and Great Society in particular. I’m reminded of a Washington Post interview with Howard Dean in 2003 in which he explained his nostalgia for that era:

“Medicare had passed. Head Start had passed. The Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, the first African American justice [was appointed to] the United States Supreme Court. We felt like we were all in it together, that we all had responsibility for this country. … [We felt] that if one person was left behind, then America wasn’t as strong or as good as it could be or as it should be. That’s the kind of country that I want back.”

“We felt the possibilities were unlimited then,” he continued. “We were making such enormous progress. It resonates with a lot of people my age. People my age really felt that way.”

That’s not how people his age felt back then. It’s how a certain group of liberals felt because they were winning. The 1960s and the 1930s were times of massive civic strife marked by race riots, domestic bombings, assassinations, and anti-war protests. But liberals were in charge, felt like history was on their side, and they had a lot of “wins” as Donald Trump might say.

The current obsession with the “new Jim Crow” seems like a perfect example of how liberal nostalgia distorts and corrupts. As I write today, I’m not a fan of the arguments coming out of the GOP or the Democrats. But the simple fact is that we don’t live in the 1960s—or 1890s—anymore. Whatever the future holds, it will not be a replay of that past. And that’s overwhelmingly for the good.

I always find it funny that the same people who ridicule “excessive” fidelity to the timeless principles of the Founding as archaic are often also the same ones who worship at the altar of the New Deal and the Great Society. The Founders didn’t know about mobile phones and the internet! Well, neither did the New Dealers or the Johnson administration. But that doesn’t matter because the part they really liked and yearn to restore is timeless: people in Washington deciding how Americans everywhere else should live and work.

I don’t know how the White House’s new collaboration with Facebook to combat “misinformation” will actually play out and I’m not fully up to speed on what the administration really intends to do. Though—given press secretary Jen Psaki’s comment that “you shouldn’t be banned from one platform and not others,” etc.—it doesn’t sound good. But I think David French’s gut check is exactly right: “Moderation is a platform decision, not a White House decision. Trying to force more moderation is as constitutionally problematic as trying to force less moderation.”

The principle at the heart of that speaks not just to social media regulation, but to all of the competing efforts from right and left to throw aside the rules in a thirsty search to rule.

Making peace with superfluity.

Listeners of The Remnant know that I often find myself suffering from a peculiar form of nostalgia, for want of a better word. The title of my podcast comes from an essay by Albert Jay Nock, who was one of the “superfluous men” of the long Progressive Era that stretched—with a brief, and partial, parentheses under the sainted Calvin Coolidge—from the end of the Teddy Roosevelt administration to the end of the Franklin Roosevelt administration. I don’t agree with Nock, or the other superfluous men, on everything—they were a diverse lot. But the thing that connected them all—hence their superfluousness—was how they felt that they were standing on the sidelines as the major combatants at home and abroad competed over how best to be wrong, how to stir up populist anger for their agendas, and, most of all, how to use the state to impose their vision on the “masses.” The remnant was the sliver that wanted no part of any of it.

“Taking his inspiration from those Russians who seemed superfluous to their autocratic nineteenth-century society and sought inspiration in the private sphere, even to the point of writing largely for their desk drawers,” writes Robert Crunden, Nock’s biographer. “Nock made the essential point: ransack the past for your values, establish a coherent worldview, depend neither on society nor on government insofar as circumstances permitted, keep your tastes simple and inexpensive, and do what you have to do to remain true to yourself.”

Or as the great superfluous man of the Soviet Empire, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, put it, “You can resolve to live your life with integrity. Let your credo be this: Let the lie come into the world, let it even triumph. But not through me.”

I share this—yet again—as a kind of omnibus response to all of my critics these days and the ones yet to come. I’m lucky that I don’t have to write for my desk drawer, though I am reliably informed — daily — that many people would prefer I did. But I am going to continue to write for the remnant as I see it and those I hope to convince to swell its ranks, and not for those who think that to be against what “they” are doing I must endorse what “we” are doing. Our politics may be a binary system of competing asininities these days, but just because one side of a coin is wrong, that doesn’t mean the other side is right.

Various & Sundry

Animal update: The beasts are hot. It’s hot. And they almost don’t like it as much as me. Though Zoë and Pippa still understand that some work must be done. There’s not much new to report on that front, but I did visit my mom this week and caught up with Fafoon and Paddington (Winston stayed hidden the whole time). My late sister-in-law’s cats no longer live there. They had to find new homes because they just couldn’t deal with new cats, and neither could the established feline rulers of my mom’s house. Fafoon in particular found it very stressful to have new cats around and picked up the habit of bunkering in a basket for long stretches. She still does it. Anyway, we’re leaving town for a week. But the dogs are going to stay with Kirsten and we’ve arranged for Gracie to have a handmaiden at our house.

ICYMI

And now, the weird stuff

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.