Q (and A) Branch

With one more week to go, I just want to take a moment to thank all of you for reading this quirky little campaign newsletter. We wanted to give you something beyond horse-race punditry—a peek behind the curtain of how campaigns are run and the strategic decisions campaign operatives think about when they see the same news you do.

In that spirit, I get wonderful emails from a lot of you with great questions that I try to answer. So this week, I’m going to share some of your most frequent questions (some of which I have combined/edited) and my best attempt to answer them!

-

Do you trust internal polls vs. public polls? I would think an internal Pepsi poll would say it is more popular than Coke but we know that’s not true. Aren’t internal polls inherently biased?

First, let’s understand why internal polls exist. While campaign pollsters will always ask the question ‘who do you intend to vote for,’ this isn’t why campaigns pay $20-$50K for a poll. Internal polling is a tool a campaign uses to make strategic decisions about money and time. If strategists just wanted to know who was winning or losing, they could rely on all these great public polls.

Instead, a campaign uses internal polls to decide where to put resources and who their messages—both positive and negative—are resonating with. A campaign may put a poll in the field to test the opposition research it has against an opponent to see what could stick. A campaign may want to see whether its candidate is doing better in Florida or North Carolina to decide where to send her candidate in the final stretch.

And most importantly, internal polls can oversample cross tabs. (What a great jargony nonsense sentence, right? Stand by, I’ll explain.) Cross tabs—the tables that break down how specific demographic groups responded—are a big reason why internal polls exist. A public poll might have 900 respondents with a margin of error of 3 points. Roughly 450 are female. And of those, 150 are females over the age of 55. So when a public poll shows that Biden is “winning female seniors” by 30 points, they are basing that on 150 respondents; not 900. As you might have guessed, that drastically changes the margin of error. An internal poll allows you to poll 900 people still, but it can ensure that 300 of the 900 are senior women and adjust the weighting of the poll accordingly. Now your margin of error is smaller and the campaign has much better data on how they are doing with that demographic.

And yet, you are thinking to yourself: But I see “the campaign’s internal poll shows them up by 3 points” all the time. Yes, you do. But think of the internal poll like a buffalo. The campaign wants to use all the parts of the poll. So the fundraising team will use it to tell voters that the candidate is doing well with senior voters. The field team will use it to prioritize which doors to knock and voters to call. The folks in debate prep will look at which attacks drive down support for their opponent.

And then there’s the communications team. If a poll has a good message, they release it. If it doesn’t, they don’t, or they get cute with their phrasing to make it look better than it actually is. So that means that internal polls are great and usually quite accurate. But what you are seeing as a news consumer is cherry-picked.

-

President Trump just had 20,000 people attend a rally in Gastonia, NC. I had never heard of Gastonia, NC before. I do not understand how someone who is losing by 10 percent can do this in a place I’ve never heard of. Actually, I don’t understand how even a person who is winning by 10 percent can do this.

I also had never heard of Gastonia, NC, but luckily Google Maps had. Turns out, this little town is really more of an exurb less than half an hour from Charlotte, NC, which has a population of 850,000. But that doesn’t answer whether 20,000 is a lot or a little or a meaningful indicator of support or turnout.

First, these rallies don’t just pop up out of nowhere. Campaigns think long and hard about where to send their candidates. They are looking at their internal numbers and also talking to their field directors to see whether they can pull together an event. From there, the field director will move most if not all of their phone banks and door knocking to turnout for the event. In this case, they are likely trying to target voters who are already firmly supporting Trump but maybe didn’t vote in the 2018 midterms.

The theory is that rallies have the same effect as getting folks to donate under $20. It’s not the attendance at the rally or the amount of money, it’s building attachment to the candidate by ensuring the voter has psychologically invested. When voters attend that rally, they are surrounded by other supporters and subconsciously start to identify themselves as part of a group, “Trump supporters.” Group identity, of course, is great if you want to boost someone’s chances of voting. They become defensive of the group and—at least the campaign hopes—don’t want to let the group down.

On the other hand, Alan I. Abramowitz, a professor of political science at Emory University, ran numbers from 2016 and found “the relative number of campaign trips to a state by Trump and Clinton had no effect on the results.” Interesting.

But back to Gastonia. Trump-leaning voters in Charlotte probably got bombarded with texts, emails, and phone calls in the run up to the event. Field directors are masters at knowing how many people they can turn out in their area for an event based solely on the day of the week and the campaign surrogate (i.e. there’s a big difference between an event featuring Joe Biden and one with Jill Biden).

Trump got 20,000 people near a city with 850,000. Does this mean the polls that show Trump down 1-2 points are wrong? They may be wrong, but this provides zero evidence for it. For me, rallies say far more about the talent of the field team than about the popularity of the candidate.

My evidence: In October 2012, Mitt Romney had 14,000 people in Fishersville, VA, 40 minutes outside of Charlottesville (population 45,000). He lost Virginia by 4 points.

-

Can you explain why Biden and Harris are traveling to Texas and Georgia this week? How does this make any sense?

Imagine if the scoreboard broke in the final 2 minutes of Game 7 of the NBA championship. LeBron has the ball, and the last he saw, his team was up by 2 points. But he’s lost track of the last few possessions. He’s pretty sure they are still up by 2, but he could be wrong. He has an easy path to the layup—a guaranteed 2 points to win the game. But instead he wants to dunk the ball in a new and awesome way because that could increase his endorsements after they win the championship and he could then surpass Michael Jordan for the most expensive endorsement contract in history.

The problem is this move runs a low but non-zero risk that by attempting this new and awesome move that has no bearing on winning the game, the ball will bounce off the rim, causing LeBron to fall backward onto his head, get a concussion, and lose the game and the championship and all those endorsements. Should he do it?

(But it definitely can psych out your opponent to play on his home turf.)

-

What chance is there that, because we are a no land-line couple, and don’t answer calls not recognizable to us, we missed being polled altogether? As a household with one Republican and one Democrat, we ought to be interesting, but have not, to our knowledge, had the chance to respond to a pollster.

Let’s look at Florida. There have been about 40 Florida polls in October. Most polls report between 600 and 1200 respondents. Pollsters report a response rate of 5–7 percent. That’s probably around 700,000 people who were called for those polls. There are 14 million registered voters in Florida. So even in one of the most-polled states in the country, you had a 95 percent chance of not getting a call for one of those polls in October.

-

If Biden wins by 5 points nationally, could there be enough split ticket voters to save some of these [Republican] senate candidates?

Or to put it another way: If Trump loses a state like Iowa, can a Senator like Joni Ernst survive?

Undoubtedly, there are quite a few conservative voters who don’t like Trump but nevertheless want Republicans to retain control of the Senate, or long-time loyal Democratic voters who like Trump’s style, or voters who just like divided government.

Pew recently released a survey that showed 4 percent of voters intend to vote for a presidential candidate and a senate candidate from opposing parties. That’s down from 8 percent who split their ticket in 2016. This fits with everything we’ve been seeing about the decline of split ticket voters in general. As Pew noted, “In 139 regular and special elections for the Senate since 2012, 88% have been won by candidates from the same party that won that state’s most recent presidential contest.”

Sure, but that’s just a poll. We can also look back to 2016 to see which candidates outperformed Trump. In New Hampshire, Trump lost by .37 percent and Sen. Kelly Ayotte lost by .14 percent. Trump won Pennsylvania by .72 percent and Sen. Pat Toomey won by 1.43 percent. In North Carolina, Trump won by almost 4 points and Sen. Richard Burr won by 5. The only outlier worth mentioning appears to be Florida, in which Sen. Marco Rubio outperformed Trump by 6 points.

So while there may be 4 percent of voters who cross parties for their senate seat, don’t assume they are all Republican-Biden voters. They cross both ways and the end result is that the senate outcome in any given state is likely to look a lot like the top of the ticket.

Sweet Carolin-a

To quote the great political movie, The Campaign, when it comes to the North Carolina senate race, “it’s a mess.” Thankfully, Audrey has a piece on the site today in which she dives into the muck and mire so you don’t have to.

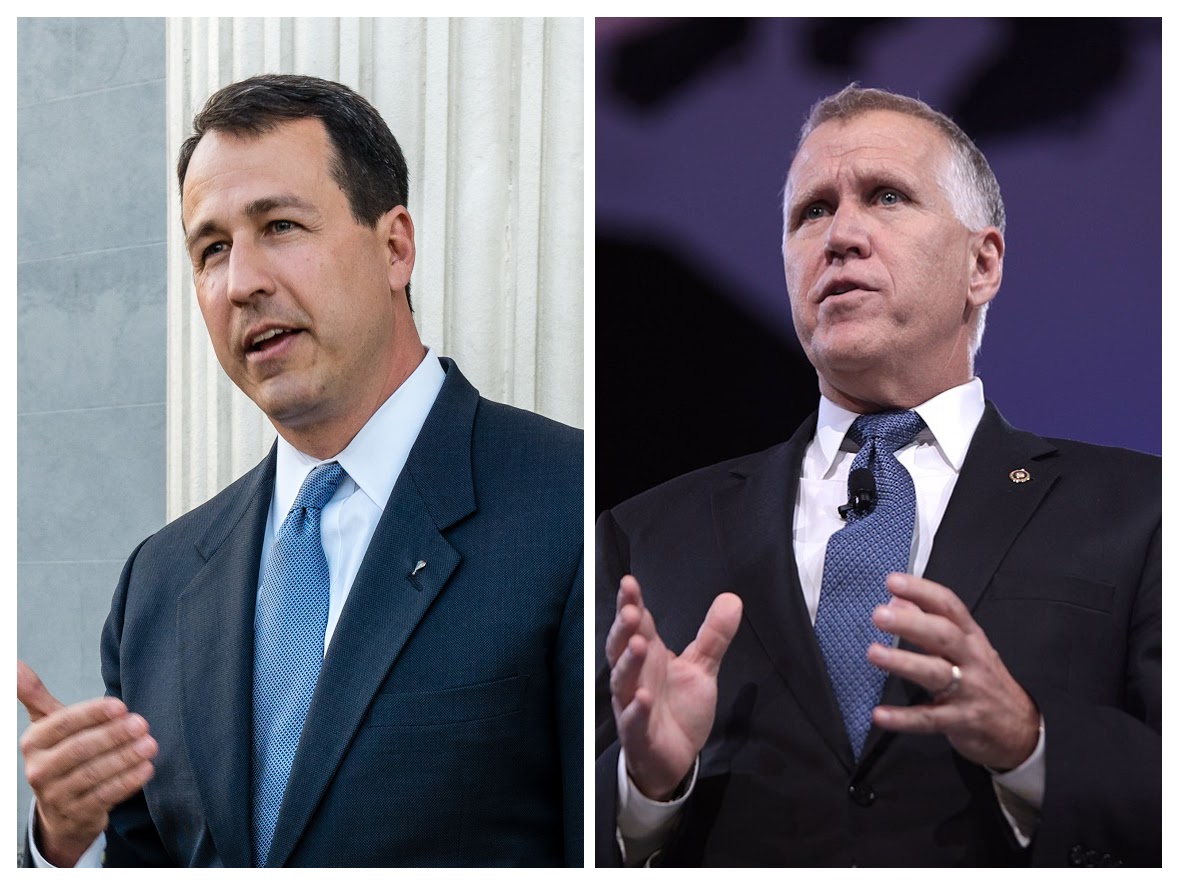

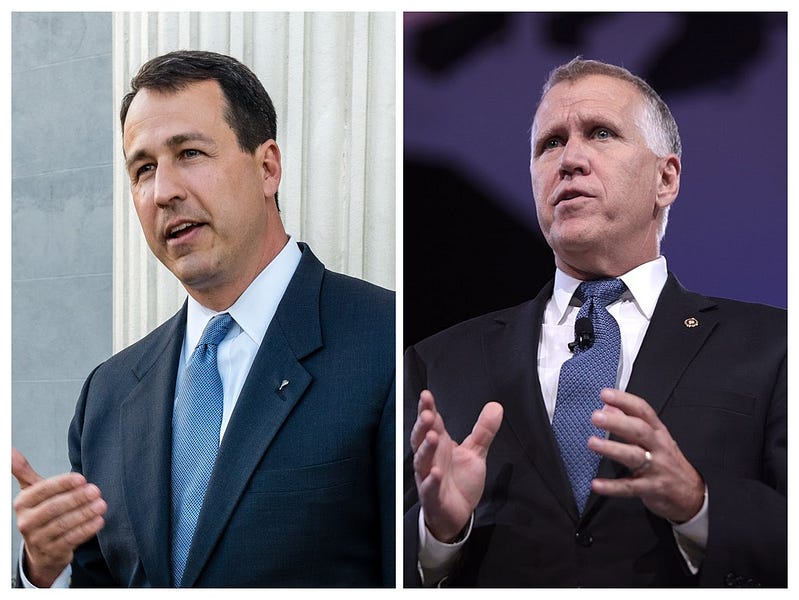

More than 3 million North Carolinians have already voted in what has become one of the most expensive, scandal-ridden Senate races of 2020: a tight matchup between first-term Republican Sen. Thom Tillis and Democratic challenger Cal Cunningham, an Army Reserve officer and former military prosecutor who served tours in Iraq and Afghanistan.

With the GOP’s 53-47 Senate majority hanging by a thread—the incumbents in Maine, Arizona, and Colorado are in serious jeopardy of losing—Republicans are hoping that North Carolina will be the linchpin that prevents Democrats from winning the four seats they need to regain the Senate. (Democratic Sen. Doug Jones of Alabama is expected to lose reelection to Republican challenger Tommy Tuberville, adding a slight cushion to the Senate Republicans’ fragile three-seat majority.)

Though Trump narrowly won the state in 2016, a growing number of unaffiliated voters in North Carolina have moved the once reliably red state into purple territory: Biden is now carrying the state by 1.2 points, according to today’s RealClearPolitics average.

But the first week of October threw a wrench into Senate Democrats’ plans to unseat Thom Tillis—a fairly anonymous senator who has suffered from consistently poor approval ratings since 2014—with Cal Cunningham, a moderate Democrat who has centered his campaign around health care and his military service. Just hours after Tillis told reporters he had tested positive for COVID-19 on October 2, news broke that Cunningham, a married father of two, was sending romantic text messages to a woman who is not his wife.

Even though the Army Reserve is currently investigating Cunningham—adultery is a punishable offense under the Uniform Code of Military Justice—Cunningham’s sex scandal hasn’t put much of a dent in his steady 2 point average polling lead over Tillis. Only 26 percent of likely voters in North Carolina voters surveyed in a recent Washington Post-ABC News poll said Cunningham’s extramarital affair is “extremely” or “very important” to their vote.

“I do think maybe there is something bigger going on and race like that [Tillis v. Cunningham], where people are kind of tired of the ‘gotcha’ politics and they just want to try and get past it all,” GOP strategist Dave Kochel told The Dispatch. “So maybe it’s just one of those things where it’s not going to help Tillis or hurt Cunningham at this point because voters don’t think it’s important enough in the race.”

Given Tillis’ relative unpopularity among base voters, the incumbent is clinging onto Trump’s coattails, knowing the electoral price today’s GOP exacts on those who distance themselves from the president.

With North Carolina’s Senate seat, gubernatorial contest, state legislature majority, and 15 Electoral College votes all up for grabs this Nov. 3, both parties are pouring advertising money into the state this election cycle. Though Biden is slightly favored to win in North Carolina, there’s a lingering hope that a narrow Trump victory in the state could pull down-ballot Republicans like Tillis across the finish line.

Photograph of Cal Cunningham and Thom Tillis from Wikimedia Commons.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.