Dear Reader (Unless you receive this “news”letter through long protein strings),

I was in a hotel in Pendleton, Oregon, on 9/11. I was there because Cosmo the Wonderdog had attended my wedding and I’d had to pick him up, along with my car, from the San Juan Islands and drive back home after my honeymoon. Pendleton was my first stop.

(Though, Cosmo was not in the actual wedding ceremony in any way. My then-soon-to-be mother-in-law said she would boycott the event if Cosmo was a ringbearer, never mind best man—even though he was the bestest boy.)

Jessica couldn’t come with me to pick up Cosmo, because she had to get back to her relatively new job as John Ashcroft’s chief speechwriter at DoJ.

For a long time, 9/11 felt like a more significant break with the past than getting married. The Fair Jessica and I had been together for a good while before we tied the knot (it took years of wooing to wear her down enough to marry me). But 9/11, as the cliché went for years after, seemed to “change everything.”

Nineteen years later, it doesn’t really feel like that anymore. I say this not to minimize the impact on people who lost loved ones, not at all. However, for most Americans I think it’s fair to say 9/11 has receded in importance. The war on terror that was sparked that day seems to have fizzled in the years since. There are still a few folks who insist that the West is in a civilizational battle with Islam, but that’s at best a niche hobbyhorse among a few specialists and, at worst, a putrid harbor for crankery. That’s not to say the threat of Islamic terrorism isn’t still with us—it’s just that it doesn’t consume people the way it once did and, I would argue, rightly so. The Iraq War still sparks controversy, but it’s not the cultural touchstone it was even a decade ago.

My point is, the view—once widely held, including by me—that 9/11 was the beginning of a new Cold War now seems wildly overblown if not a bit naive.

What’s remarkable to me is that all such predictions tend to be wrong. As I’ve written before, the single best and most concise explication of this point is a famous memo written by Deputy Assistant Defense Secretary Linton Wells. Here’s how it begins:

-

If you had been a security policy-maker in the world’s greatest power in 1900, you would have been a Brit, looking warily at your age-old enemy, France.

-

By 1910, you would be allied with France and your enemy would be Germany.

-

By 1920, World War I would have been fought and won, and you’d be engaged in a naval arms race with your erstwhile allies, the U.S. and Japan.

-

By 1930, naval arms limitation treaties were in effect, the Great Depression was underway, and the defense planning standard said “no war for ten years.”

-

Nine years later World War II had begun.

Disaster porn.

I wrote earlier this week about a different way to think about centrism. If you read my (underrated) book The Tyranny of Clichés, you’d know that I’ve long had a lot of antipathy for passionate centrists and haughty independents. But the often marshmallow-soft and pliable definitions of centrism and independence were a product of ideological difference-splitting. This new kind of centrism is more psychological than ideological. Think of a compass for our ideological landscape, with Trump and Trumpism defining the north, and all the craziness that defines the hard left/Resistance hysteria, BLM and Antifa apologists, anti-racist extremism, etc. as the south. The people sitting at east and west may be ideologically committed progressives or conservatives—but what they’re not is apocalyptic, conspiratorial, or in a constant state of panic. As I wrote:

In this climate, the new centrists can be ideologically conservative or progressive according to the old definitions, but east and west share a common discomfort with the constant demand to catastrophize our politics in order impose orthodoxy on everyone. And amid the cacophony, such centrism can be quite lonely.

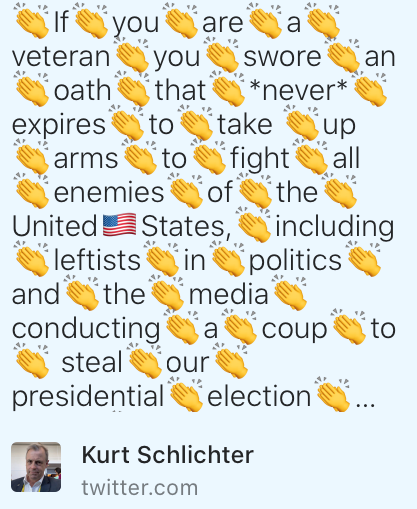

What put this in my mind was the bizarre popularity of this ridiculous piece published last weekend by Michael Anton (he of “Flight 93” fame, or infamy, depending on your point of view). Anton thinks Democrats are plotting a coup (or at least he wants you to think so). Anton deftly cherry-picks examples of Democrats saying alternately paranoid things and/or reasonable things in a hypothetical exercise. He ascribed ominous portent to the fact that Biden has said—“thrice”!—that the military will “escort [Trump] from the White House with great dispatch” if Trump illegitimately refuses to concede.

He also takes examples of current and former Trump administration figures acting responsibly or speaking reasonably and spins them into proof of a Deep State cabal undermining Trump’s sober, wise, and patriotic leadership. Sitting Defense Secretary Mark Esper advised against using the Insurrection Act against George Floyd protesters and rioters. The horror!

Reasonable people can disagree with Esper—I don’t—but it was an utterly defensible and even normal view for a defense secretary to hold. But to Anton’s ear this amounted to Esper saying, “Mr. President, don’t tell us to do that, because we won’t, and you know what happens after that.”

Never mind that Esper didn’t say that; that’s Anton’s tendentious interpretation, deployed to mount supposition upon supposition to conjure paranoia about an open conspiracy to launch a coup. The war game exercise he cites may have been dumb—I honestly don’t know. But taking what people hypothetically said in a game of make-believe in response to imagined scenarios and saying, “See! This is their plan!” is boob-bait. If you asked me what the military would or should do if Trump clearly lost the election but moved to invalidate it to stay in power, I too would say they should escort him from the building. That doesn’t mean I’m plotting a coup.

The idea that this war game was a PSYOP intended to deny Trump a legitimate election is best understood as Anton’s own effort at a PSYOP. He writes:

These items are, to repeat, merely a short but representative list of what Byron York recently labeled “coup porn.” York seems to think this is just harmless fantasizing on the part of the ruling class and its Democratic servants. For some of them, no doubt that’s true. But for all of them? I’m not so sure.

That “I’m not so sure” sounds oh so reasonable and measured. But the thrust of the piece—titled “The Coming Coup?” —is that Anton is in fact sure that there’s a potential coup in the works—or again, that he wants you to be sure. Not only is that wrong, it’s every bit as dangerous as the coup porn he’s weaponizing. (And it looks like he’s having some success. Congrats, Mike.)

The sleight of hand in Anton’s argument should be familiar at this point. He takes it as a given that everything Trump does is above board, legitimate, and reasonable. So any reaction to Trump’s own constant conspiracy-mongering and attempts at game-rigging—including the most ridiculous examples—amount to evidence that the “other side” is the crazy party.

This is a common trope among professional Trump apologists. Trump is like the nutty drunk uncle at Thanksgiving dinner who does and says outrageous things. But because Uncle Don’s behavior is priced in, your parents get mad at you for taking the bait, setting him off, or “overreacting” to him, rather than getting mad at his predictably ridiculous antics. “Why are you making such a big deal about him using the turkey as a pith helmet?”

The central assumption of anti-anti-Trumpism is that Trump should be exempt from the standards everyone else should follow because it’s absurd and somehow unreasonable to expect him to behave. Trump is Trump—“he’s a disruptor!”—and you’re the weird one if you make a big deal out of it.

But Anton takes this familiar gaslighting a step further: York’s “coup porn” description strikes me as accurate. But Anton then pretends (and yes, I think he’s pretending) that Trump is not only normal, but that the “porn” is real.

Now, I’ve argued for several years now that Trump’s irresponsible contempt for norms, institutions, and the truth invites an irresponsible contempt in response. It can take the form of indefensible leaks and maddeningly insipid media grandstanding. If you think Trump’s impeachment was entirely unwarranted—I don’t—you can throw that in there too.

The “collusion” brouhaha is a good example of how these debates are now defined by those with the most passionate intensity rather than those with the evidence. Trumpists want you to think any suspicion that Trump was in cahoots with Putin is proof of unhinged conspiratorialism. They honestly think—or claim to honestly think—it’s insane that anyone would believe that a Putin sycophant who publicly asked the Russians to hack his opponent, appointed Paul Manafort his campaign manager (currently in jail, in part for working illegally with Russians), and whose campaign met with a Russian emissary to collect dirt on his opponent would ever—ever!—work with the Russians.

The Resistance types, meanwhile, went wildly overboard with their conspiracy theories, making the entire national conversation a battle between promoters of competing cartoons. On the one side were believers in the ridiculous caricature of Trump as the patriotic hero who’d never put his own interests above the country’s, and on the other were subscribers to the idea he was a Manchurian, or more accurately, Muscovite candidate.

Oh, and it’s a bit off-topic, but you’ve got to love that it appears that Rudy Giuliani has been exposed as a useful idiot of Russian intelligence.

Elite panic

Or maybe it’s not off-topic. On 9/11 Rudy Giuliani emerged as a true statesman, having concluded what George Will called “The most successful episode of conservative governance in this country in the last 50 years.” In recent years, though, he’s become a peddler of hysteria and conspiracy theories, convinced that he’s a vital general in an all-out war, not with Islam, but with … what? Other Americans.

In 2001, if you had predicted that Giuliani would be acting like a cautionary tale about the perils of day drinking, saying and engaging in credibility-draining nonsense in service to President Donald Trump, the nurse would think it was time for your shot.

Which is to say that the future is pretty much never what you think it’s going to be.

But more importantly, we live in a country where the people most certain about what the future looks like are the most committed to a black-and-white, good-versus-evil vision of some kind of Götterdämmerung.

Giuliani’s transformation is rather typical of a vast swath of elites who are clustered at the antipodal ends of that compass I mentioned. The thing about going as far north or south as possible is that you end up someplace cold and inhospitable. Whether it’s the Antarctic or the, uh, Arctic, these apocalyptic rabble rousers can only find warmth in stoking the flames of anger and division.

Earlier this year, James Meigs wrote a brilliant essay on “elite panic.” He was writing in the context of natural disasters—floods, earthquakes, pandemics, etc. Elite panic sets in:

When authorities believe their own citizens will become dangerous, they begin to focus on controlling the public, rather than on addressing the disaster itself. They clamp down on information, restrict freedom of movement, and devote unnecessary energy to enforcing laws they assume are about to be broken. These strategies don’t just waste resources, one study notes; they also “undermine the public’s capacity for resilient behaviors.” In other words, nervous officials can actively impede the ordinary people trying to help themselves and their neighbors.

Meigs also noted that “Elite panic frequently brings out another unsavory quirk on the part of some authorities: a tendency to believe the worst about their own citizens.”

We’ve seen quite a bit of this during the pandemic. But I think his observations have broader applications. I think we’re in the midst of what could be called a “cultural disaster.” I don’t mean this in the apocalyptic sense, I mean it descriptively. Social media, the rapidity of change in sexual mores and norms, the long tail of our racial past, the surplus of overeducated workers, automation—the list goes on and on. These forces have rolled over existing institutions like a hurricane, uprooting homes and churches, and sending them downstream on floodwaters. It’s worth remembering that every upsurgence in populism in American history came at a time of disruption—economic, technological, or both.

The response from many elites—at times including myself—has been a version of the panic Meigs describes. National elites, senators, talk show hosts, pundits, authors, movie stars, and others think that the rebuilding effort must be led from above, usually from Washington. And just as Meigs describes during earthquakes, they think they know better than the people on the ground how to adapt and fix things. They clamp down on information by only telling one side of a story, usually with ample exaggeration and fear-mongering. What better way to control the untrustworthy masses?

Real problems and challenges—racism, campus rape, police abuse, global warming, social media censorship—are routinely recast as existential crises demanding social engineering from above, on the assumption that the people closest to the actual problems are too dumb, too bigoted, or too corrupt to deal with them. Worse, relatively trivial incidents are blown up into slippery-slope fear mongering.

George Orwell once noted that during World War II, elites were much more likely to veer from defeatism to triumphalism about the course of the war than average Britons. If the military had a victory, the intellectuals would do a straight line prediction that they would continue to have victories. If they had a defeat, they predicted the reverse. Meanwhile, normal Brits took the wins and losses in stride, buoyed by a confidence that things would work out in the end. I think this was partly due to the fact that elites have the luxury time and sometimes the professional requirement of fretting about trends, patterns, tea leaves, etc. That’s what elites do. Normal people muddle through and tackle problems as they encounter them.

In all my travels this summer, I talked to a lot of “normal” people—a phrase folks in my line of work often use to describe the saner among us who don’t obsess about Beltway arguments and abstract Twitter feuds. Their views varied. But one thing that united most of them was a generalized contempt—whether from the left or the right—for the people screaming on their TVs when they occasionally tuned in to the “news.”

I don’t know what the future holds—again, no one does—but I’m relatively optimistic about it because I think there are a lot more of those people than our panicked elites imagine.

Various & Sundry

If you’re reading this, there’s a good chance you’re already some kind of subscriber to The Dispatch. But if you’re not a full member, you have a chance to test it out free of charge. We’re running a 30-day trial of the full product line. Obviously, we hope some—heck, many! —of you will like the wares enough (including the members-only Wednesday G-File) that you’ll sign up at the end of the trial period. If any of the above speaks to you, I think you’ll like what we’re offering.

Canine (and Feline) update: The biggest change after our long absence is that Ralph has become radically more tolerant of me, particularly at treat time. Usually, he would wait for the Fair Jessica to arrive to take his ration from her. But now he is perfectly willing to accept treats, and even a little affection from me. He even showed up first today. And he’s becoming more strident as well. But Gracie is still queen.

I’ve been getting a lot of complaints from members of #TeamZoe that she doesn’t get enough camera time. I hear you. The problem is that it is almost impossible to get Zoë to pose when we’re outdoors. She has perimeters to patrol (indoors is a different matter). But because of Pippa’s ball addiction, she’s veryeasy to stage. We’re still trying to ratchet down the fetching with Pippa, but she gets enough to prevent going through withdrawal.

Bonus Content: As many of you know, my mom has some very exotic cats, including the Empress Fafoon. These are her half-siblings.

ICYMI

The Dispatch Podcast, in which the gang discusses Jeffrey Goldberg’s (no relation) investigative reporting on Trump

And now, the weird stuff

Photograph by Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.