Hurricane Helene’s death toll continues to rise each day, and hundreds of people remain missing as recovery efforts move forward. Parts of seven states are under major disaster declarations, and relief efforts have been hampered by damaged roadways. Given the magnitude of Helene’s destruction, even the most engaged political observers have exhibited some reluctance to talk so soon about the storm’s potential electoral impact.

But the state most affected by the hurricane—North Carolina—is one that will help determine which candidate moves into the White House in January. Donald Trump won the state in 2020 by 74,483 votes (or 1.3 percent of the 5.5 million votes cast), so even the slightest shift in the electoral landscape deserves attention.

There’s nothing slight about Hurricane Helene. Hundreds of thousands of North Carolinians had no electricity days after the storm. Many residents have lost their homes and businesses entirely. Sections of major roadways remain closed, including at least one stretch of interstate that could be out of commission for a year.

“I would be remiss if I didn’t ask us all—political analysts, journalists/reporters, campaigns and their operatives, and the general public outside the 25 counties of FEMA designation—to remember these are fellow North Carolinians who have been impacted in a such a manner that very few of us can fully comprehend and realize the magnitude of what they will be confronting for months, if not years,” wrote Michael Bitzer, professor of politics and history at Catawba College in Salisbury, North Carolina, on Wednesday. That request preceded Bitzer’s demographic and electoral analysis of affected western North Carolina counties for his Old North State Politics blog.

Politics might not top the priority list now, but North Carolina’s general election has started already. Officials have mailed out more than 200,000 absentee ballots statewide, including 39,728 through Wednesday to voters in 25 western counties covered by a federal major disaster declaration for Helene. Just 1,499 of those ballots had been returned. Voters must register by October 11 to participate in the general election, and early voting begins on October 17.

The election season moves forward despite the disruptions.

Election administration challenges.

North Carolina’s State Board of Elections continues to assess Helene’s damage. “This storm is like nothing we’ve seen in our lifetimes in Western North Carolina. The destruction is unprecedented, and this level of uncertainty this close to Election Day is daunting,” said Karen Brinson Bell, executive director for the state elections board, during a media briefing Tuesday. “We are taking this situation one step at a time, and this will be an ongoing process between now and Election Day.”

Five county elections board offices remained closed in western North Carolina as of Thursday. Those that had reopened were looking into the accessibility of polling places for both early voting and Election Day.

This year will be the first time North Carolina’s photo voter identification law is scheduled to be enforced for a general election. Officials are preparing to deal with voters who lost their IDs or will be unable to obtain a valid ID by the time they head to the polls.

Even before Helene hit, the state elections board had been the subject of lawsuits over various aspects of election administration. State law gives the governor’s party a 3-2 majority on the elections board. The current Democratic majority already faces four active lawsuits from the Republican National Committee and North Carolina Republican Party. The elections board can expect further legal action if GOP groups consider its emergency actions to favor one party over the other.

Presidential politics.

Trump himself injected a political element into North Carolina’s Helene recovery efforts on Tuesday. In a social media post, the former president and current Republican nominee explained that he planned to bring supplies to the state once his presence wouldn’t compromise local emergency management efforts.

“I’ll be there shortly, but don’t like the reports I’m getting about the Federal Government, and the Democrat Governor of the State, going out of their way to not help people in Republican areas. MAGA!” Trump wrote on his Truth Social platform.

“He’s lying, and the governor told him he was lying,” President Joe Biden responded later that day when reporters asked him about Trump’s comments.

The federal major disaster declaration issued on September 28 covered 25 western North Carolina counties, plus Cherokee tribal land in three additional counties along the Tennessee and Georgia state lines. Trump won 26 of those 28 counties in his 2020 reelection bid and outpolled Biden in that region, 604,119 to 356,902. That’s nearly 250,000 votes in a state decided by fewer than 75,000 votes in 2020.

Even if one removes Catawba, Cleveland, Gaston, and Lincoln counties, which are populous Charlotte-area Republican strongholds that sit on the eastern edge of the disaster declaration area, Trump outpolled Biden, 404,359 to 260,025 in the other 24 counties in 2020. That’s a victory margin of 144,334, still nearly twice as large as Trump’s statewide win total.

Bitzer, the Catawba College political scientist, scoured available data to learn more about the 1.3 million registered voters in the 25 disaster-declaration counties.

“When we talk about the political dynamics of the Helene-impacted counties in North Carolina, we’re describing a more Republican, more rural, older, and more-White voter population that is ultimately about 17 percent of both the registered voters and actual votes cast in the 2020 election,” Bitzer wrote in his Wednesday post.

While Helene affected primarily “red” counties, the storm’s impact could present challenges for supporters of both major parties: Asheville’s Buncombe County voted for Biden by significant margin in 2020, 96,515 to 62,412.

Implications for voter participation.

Groups that focus on voter turnout are adjusting their plans.

“While voting in the upcoming election might not be top of mind for those who have been impacted, our organization is working to ensure those who have been affected or displaced by Helene will have access to the ballot and remain eligible to vote this fall,” the left-of-center activist group Democracy North Carolina wrote in a Wednesday news release.

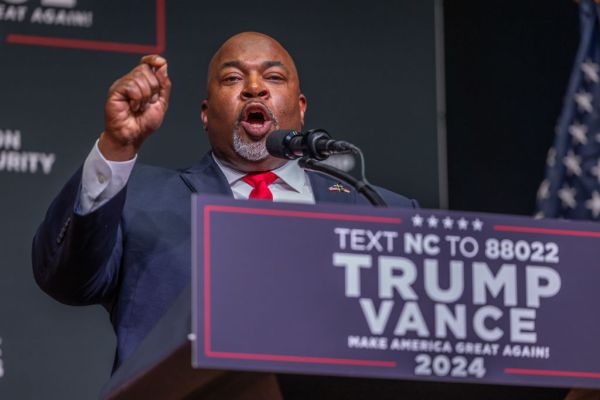

Dallas Woodhouse, former state executive director of the North Carolina Republican Party, now works as state director for American Majority Action. Long before the storm, that group was working to assure voters that North Carolina’s 2024 elections would be fair and secure. The group also promoted early-voting options.

“As our neighbors, friends and family in western North Carolina deal with horrific losses of life, property, income and security, it’s important that we make sure these citizens don’t lose their voice in the political process,” Woodhouse told The Dispatch. “We at American Majority Action are already having conversations with people across the political spectrum on how to guarantee citizens the ability to vote in the flood disaster areas. We don’t know exactly what that looks like, but it will be a monumental effort.”

“As far as what side may or may not benefit from the changes in the electorate, we don’t know and we don’t care,” Woodhouse added. “We are all citizens, neighbors and friends. This is so beyond partisan politics. … It would be an ironic shame if the people who most need strong representation in the national and state legislatures play no part in selecting those representatives,” he said.

Bitzer, for his part, will watch how local elections boards “respond to what may need to be a wholescale revamping of their early voting administration, along with potential changes to polling locations for November 5,” he told The Dispatch in an email. Much will depend as well on North Carolina’s Republican-led General Assembly, “with potential funding and some consideration of more ‘voting convenience’ approaches that may be required,” Bitzer added.

He also will keep tabs as the state posts local voting numbers in the weeks ahead. “My suspicion is that voting may be low on many impacted citizens’ minds at this point, so maybe they wait until November 5 when things have settled, and they can concentrate on voting,” Bitzer said.

Chris Cooper, professor of political science and public affairs at Western Carolina University and author of the book Anatomy of a Purple State, normally would spend late September and early October blanketing social media with analysis of polling data and electoral trends.

This year, Cooper posted photos and video of rushing floodwater and depleted grocery store shelves. He offered followers an update on road conditions near his home in downtown Sylva, North Carolina. His home internet had returned just hours before The Dispatch reached him with questions about Helene’s political impact.

“It’s going to be very location-dependent,” Cooper said in an email. “Parts of the mountains are absolutely devastated — homes lost, streets disappeared, mountainsides sloughed off. Other places made it through with some inconveniences and communication interruptions, but they’re otherwise okay. And these places may just be a few miles away from one another.”

“So, for one family, their attention to the election and voter turnout may be unchanged, whereas for another, it may fade deep into the background,” he added.

“The real impacts on the election are going to be on election administration,” Cooper said. “If a county had, for example, five poll workers to staff an early voting location on a given day and two of those poll workers had to leave the region, what will happen? What if a polling location is flooded? Elections are run by people, and many of those people just experienced a massive interruption to their lives.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.