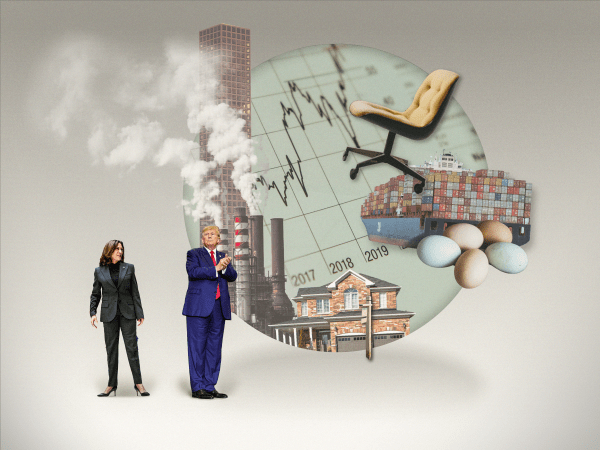

I have before observed that the great tragedy of the 2016 electoral contest between Donald Trump and Hillary Rodham Clinton wasn’t so much what the race was as what it wasn’t: a campaign for mayor of New York City.

Mayor of New York is a big job in politics, or at least it used to be (one can imagine Rudy Giuliani as Norma Desmond: “I am big—it’s the politics that got small!”), and it is a job for which either Trump or Clinton would have been reasonably well-suited. Trump’s only real nearly unqualified success in public life was (or had been) a local project in Manhattan (he led a renovation of the Central Park ice-skating rink) and Clinton, who has always and at every turn been overestimated in her public life, probably should not have begun her career in elected office serving as a senator from a state in which she had never lived, a job she took very lightly as she sat around waiting to be made president.

Trump’s lack of fitness for the presidency has—this is a kind of historical oddity—been made even more clear by his having served one catastrophic term in that office, during which his laziness, his incompetence, and his penchant for caudillismo were laid quite bare for public inspection. Kamala Harris is a bit like Clinton in that she was elected to the Senate from a state so entirely dominated by her party as to make the general election a practical formality (California’s Democratic primaries are another story, of course) and then became the Democratic nominee after having been carried to the threshold of the White House by an old-fashioned white-guy moderate Democrat and pushed to the forefront by very little other than a sense of inevitability, by a vague feeling among Democrats that it was “her turn.” As with Clinton’s tenures in the Senate and the State Department, Harris’ career in the Senate and in the vice presidency contains no evidence of an obvious future president, or even evidence of a future nominee.

If Trump is a Mr. Hyde who has deleted Dr. Jekyll’s number from his phone, then Harris is Lord Jim, a figure who was supposed to have been heroic but fell just short of the mark (“He was an inch, perhaps two, under six feet,” is the first thing Joseph Conrad tells us about the ingratiating clerk), an essentially passive character who “had the gift of finding a special meaning in everything that happened to him.” And so 2024 is a genuine clown show: Pennywise vs. Cooky, the monstrous predator vs. the frustrated aspirant who seems doomed to remain forever Vice Bozo.

“We must appreciate that the personification of Justice holds a scale in her hands on the assumption that what will be discovered in them is not equality but difference.”

Part of the clown show is pretending to take them seriously when they talk about ideas and policy proposals. Trump is pure shill, which is his natural state: Casino waiters and waitresses? No income tax! Oldsters on Social Security? No income tax! People with car loans they can’t afford? Less income tax! Harris, who seems to have graduated from the politicians’ version of an improv seminar, has mostly been “Yes, and”-ing Trump: No taxes on tips, and … joy!

Or something.

Sometimes, it is worth taking the time to meditate on the obvious. Personnel is policy, the cliché insists, but that isn’t all: Personnel is power. And that’s really what’s going on here. Trump’s view of political power is simply a generalized application of that famous proverb from his old friend Roy Cohn: “Don’t tell me what the law is—tell me who the judge is.” Harris’ view is a very slight variation of the same thing. All of Washington’s legislative directors and policy wonks and think-tank nerds are like the kids who work painstakingly to perfect the bylaws of the student council, while Trump and Harris are contented simply to get themselves elected and then ignore those bylaws—and the Constitution, and everything else. I suppose that qualifies as a kind of crude realpolitik.

The sobering fact is that Americans are going to elect one of these two people president—without having any real idea of what either would actually do in office. Their deficiencies do not seem to me parallel or of equal weight, but, though I do not share the view, there are people I respect who are so absolutely terrified of Harris that they will pull the lever for Trump even though they comprehend exactly what he is. We can probably take Trump at his word about the core of his agenda—“retribution”—but no one really knows what that would look like. Harris’ affect is more conventional, more bureaucratic, and more blasé, which is to say she is more like one of the middle managers in 1984 than she is like Big Brother. The history of the totalitarian projects of the 20th century should leave us other than heedless about the evil that middle-management types can do.

All that being stipulated, we must appreciate that the personification of Justice holds a scale in her hands on the assumption that what will be discovered in them is not equality but difference.

In 2016, I published a short (and entirely inconsequential) pamphlet titled The Case Against Trump. A few days after Roger Kimball commissioned it from me, he called me up with a mind to canceling the project, in the belief that, surely, Trump would not be on the political scene long enough for me to complete the work and get it into print. Well. I could have written a new Case Against Trump book 20 times as long for this year, with 200 pages of footnotes at the end. (I do not think that my friend Roger would have been inclined to publish it.) But the case against Trump is a case for Harris only under the narrowest kind of political understanding—all that shallow, silly stuff about that convenient phantasm, the “binary choice.” And a case against Trump is something more than a case against Trump, too: It is a case against the Republican Party in its current character, and it is an indictment of the conservative movement’s decades-long, self-serving, and, at times, calculatingly amoral embrace of atavistic populism, a sneering and destructive mode of rightist activity facilely resorted to even by such refined persons as William F. Buckley Jr. (I have no doubt that if he had been presented with the reality of two adjacent republics, one governed by the faculty of Harvard and the other governed by the first 2,000 names to appear in the Boston telephone directory, that Buckley would have chosen to reside in the former as its chief critic rather than in the latter as its chief celebrant.) There are many of us conservatives who would like to say with the Polish sage, “Nie mój cyrk, nie moje małpy”—”Not my circus, not my monkeys”—but that isn’t quite right.

In 2016, it was reasonably defensible to argue: “Yes, Trump is a poisonous buffoon, but I prefer him to the alternative.” By 2020, that line was a good deal less defensible—but it was hard to say so if you were a public figure who had supported Trump in 2016 and did not wish to admit how stupid and selfish you had been. In 2024, Republicans have taken to trying to defend that same familiar line—lamely—by pretending that Kamala Harris is something other than what she is, i.e., that she is a Marxist militant (goodness gracious, they’re even calling daft old Joe Biden a Marxist, as though he had read a book), that she is someone plotting to install an authoritarian regime, etc. What she is in reality is bad enough for most purposes—but not for every purpose. Donald Trump is an ailing, dim, mentally unstable moral grotesque who attempted to stage a coup d’état the last time he lost an election. If your case for Trump is “Yes, but,” then you are going to have to tell me something about Kamala Harris that I do not already know. Maybe there is a persuasive case to be made. But I haven’t heard it.

Eighteen days to go.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.