Sometimes—okay, fine, most of the time—we here at Capitolism tend to get stuck in the economic policy weeds, dissecting this or that discrete issue area and explaining (usually) a better way forward. But occasionally it’s good to simply step back and take stock of where things are with the U.S. economy, especially with the presidential election less than a week away and at least one major party candidate—and his surrogates—constantly declaring the United States to be a terrifying economic wasteland.

This is, to put it mildly, insane, but it’s also nothing new. For decades now, pessimists on the right and left—and especially in politics—have talked down the U.S. economy and talked up whatever economy might happen to be riding high at the moment, usually thanks to gobs of government subsidies and other seemingly brilliant economic plans coming out of their capitals. Yet time and again, the American Prosperity Machine proves the naysayers wrong and forges ahead. This time, it appears, is no different. And, while the U.S. economy surely has some issues (our messy politics being one of them), the latest data beg today’s naysayers to answer a simple question: Where else would you rather be?

Checking In on the USA

The entirety of last week’s edition of The Economist was dedicated to documenting the U.S. economy’s continued global dominance—a win streak that people here and abroad have repeatedly said was destined to end but … never has. The whole report is worth a read, but here are the main points supporting their #USAUSAUSA thesis:

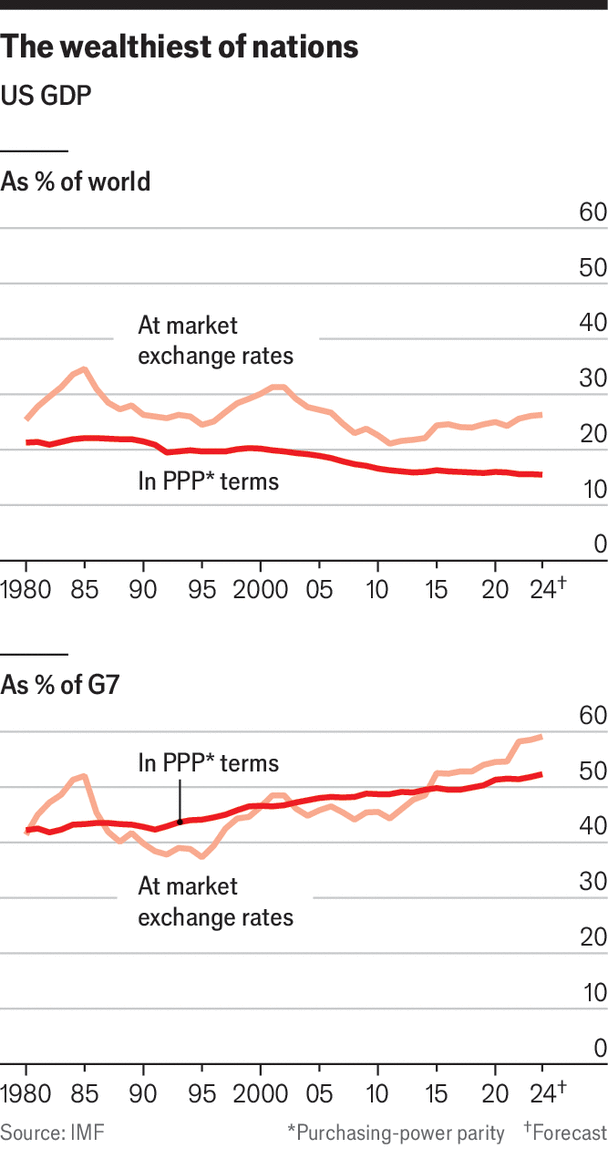

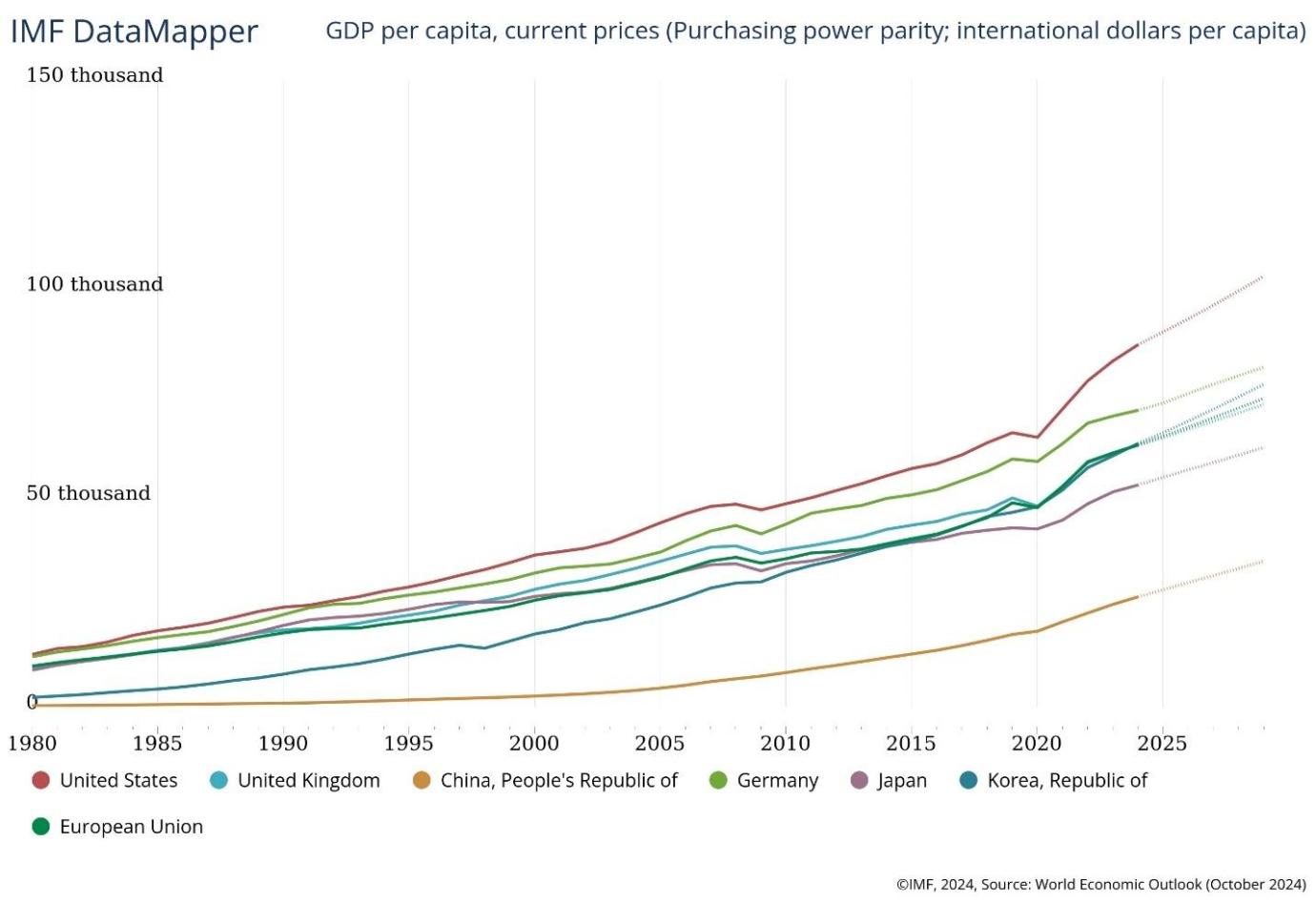

Economic output. Yes, real (inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product is an imperfect metric, but it’s still probably the best overall tool we have for measuring across countries both living standards (on a per capita, “purchasing-power parity” basis) and global economic influence (total, at either PPP or current exchange rates). And here, the USA is still killing it:

China’s output per person remains less than a third of America’s; India’s is smaller still. … In 1990 America accounted for about two-fifths of the overall GDP of the G7 group of advanced countries; today it is up to about half. On a per-person basis, American economic output is now about 40% higher than in western Europe and Canada, and 60% higher than in Japan—roughly twice as large as the gaps between them in 1990. Average wages in America’s poorest state, Mississippi, are higher than the averages in Britain, Canada and Germany. And America’s outperformance has accelerated recently. Since the start of 2020, just before the covid-19 pandemic, America’s real growth has been 10%, three times the average for the rest of the G7 countries.

Seemingly not a week goes by without yet another reminder of the United States’ relative GDP outperformance. Here are two more from just this morning.

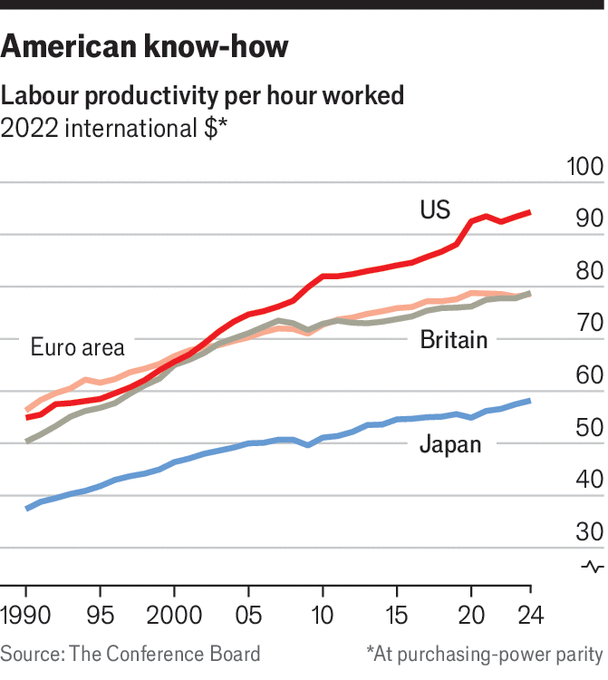

Productivity. Part of what drives the United States’ strong growth and relatively high wages is—as we just discussed a few weeks ago—our continued and growing productivity gains. Some of this is because Americans work harder and longer than many people abroad, but not all or even most of it is owed to our work ethic:

This year the average American worker will generate about $171,000 in economic output, compared with (on purchasing-parity terms) $120,000 in the euro area, $118,000 in Britain and $96,000 in Japan. That represents a 70% increase in labour productivity in America since 1990, well ahead of the increases elsewhere: 29% in Europe, 46% in Britain and 25% in Japan. … When assessed on a per-hour basis the gap remains sizeable: 73% productivity growth for American workers since 1990 versus 39% in the euro area, 55% in Britain and 55% in Japan.

For those wondering, the comparable per-hour figures for China and India this year are a mere $19.89 and $10.40, respectively. The United States’ $94.80 average also beats out tech-heavy Taiwan ($78.40), South Korea ($56), and Singapore ($85.90). Overall, only a small handful of countries—a few Scandinavian (Denmark, Sweden) nations, petrostates, and tax havens—have better labor productivity than the much larger and far more diverse United States. And our economy’s ability to keep producing more with less has big benefits for American workers and the nation more broadly.

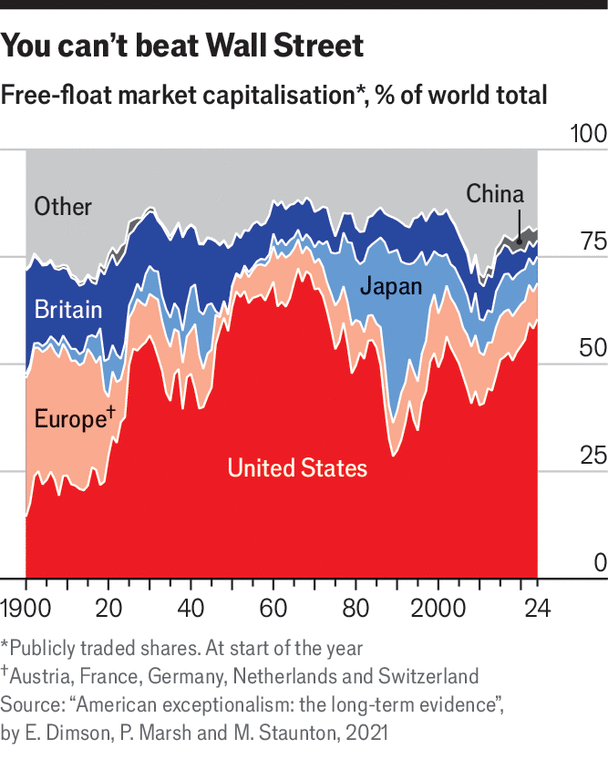

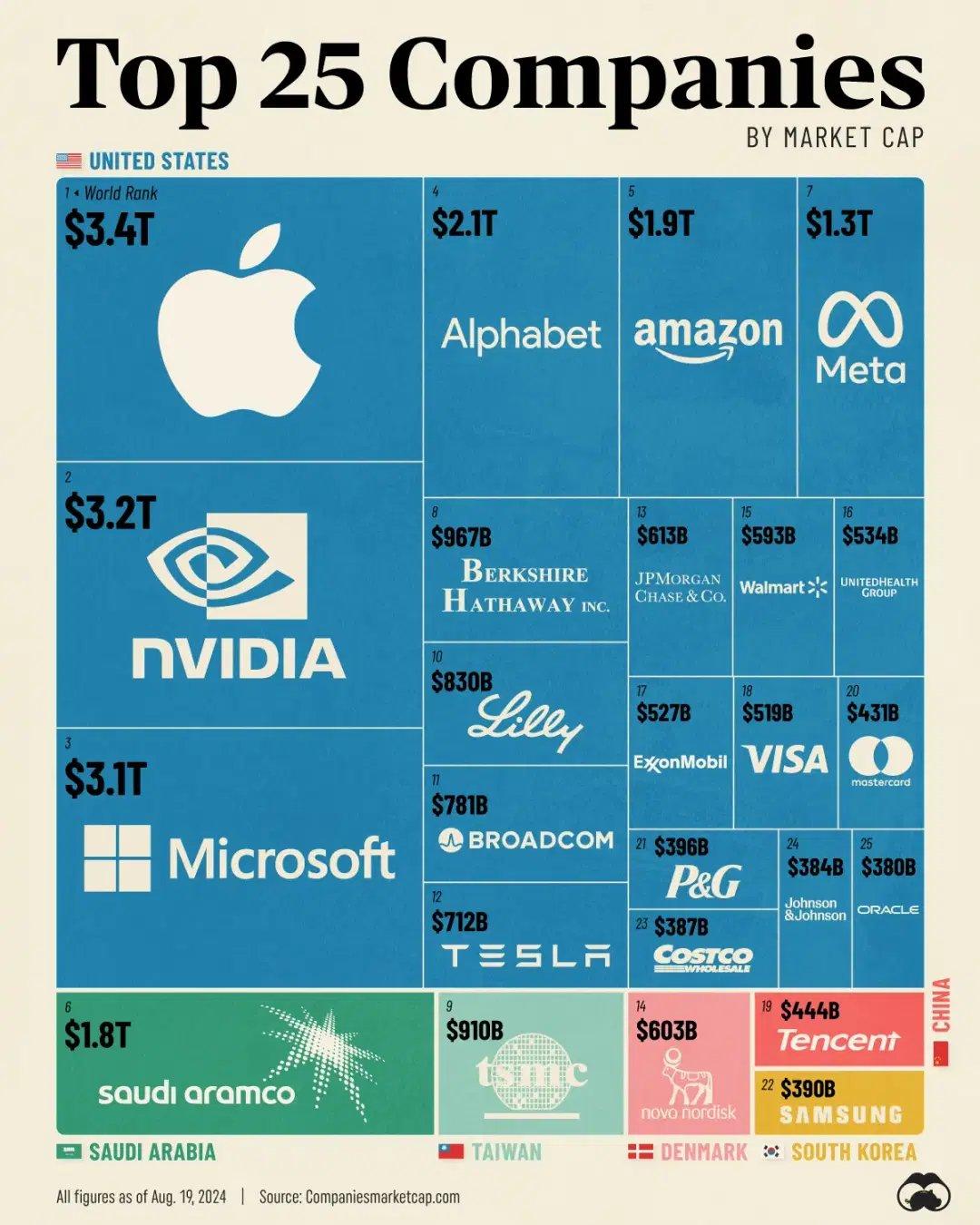

Capital markets. The United States also continues to crush it on in the stock market: Only during the 1960s was American public companies’ share of total global market capitalization higher than it is today, and that share has not only grown rapidly in recent years but has done so even though the U.S. economy is a relatively smaller slice of the global economy than it was back then (thanks mainly to wars and communism). So, why does Wall Street keep killing it?

In part it continues a long-running phenomenon. In the 20th century American equities produced a real dollar return of 7% per year, versus 4.9% in the rest of the world…. What makes America’s stockmarket unique is its combination of enormous size and high returns. Still more striking, its return advantage over the rest of the world has grown over time.

Even with our chaotic politics, moreover, experts recently surveyed by Bloomberg predicted that stocks will gain again next year, regardless of who becomes the next president. Much of the stock market’s overall dominance is owed to the current dominance of certain public U.S. firms (especially but not only tech), but we also dominate private capital markets too. And, for reasons we’ll discuss below, it’s safe to expect the United States to both attract and drive global investment in the coming years, as well.

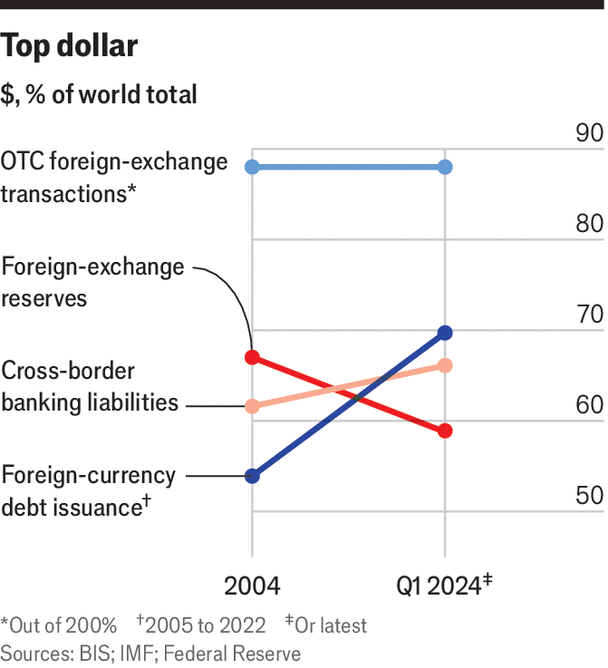

Currency. Another consistent pessimist warning is that the U.S. is on the verge of losing its status as the world’s reserve currency. And yet:

For trade, cross-border investment and foreign-exchange transactions, the dollar remains by far the currency of choice. Its appeal gives America a seemingly endless supply of credit and the power to cripple foreign financial entities with sanctions. Its strength means that at market exchange-rates America counts for over a quarter of the world economy, the same as in 1990.

The continued preeminence of “King Dollar,” The Economist notes, fuels some of the aforementioned dominance of U.S. corporations:

American assets make up over a quarter of the stock of global investment in financial instruments, up from less than a fifth in the mid-2000s, says Goldman Sachs. A paper by William Diamond of the University of Pennsylvania and Peter Van Tassel of Caption Partners, an investment firm, finds that demand for dollar assets reduces all American interest rates versus a counterfactual, not just those of the government. American firms, then, can simply borrow more cheaply.”

Demographics. As we’ve covered here repeatedly, the United States certainly isn’t getting any younger, but we’re still in a better position than the rest of the developed world and much of the developing one too—thanks to relatively strong (and steady) fertility and, of course, immigration:

Even Mr Trump, when not promising expulsions, says the country needs to bring in more skilled workers; he has mused about giving green cards to foreign-born graduates of American universities. Today, America accounts for 4% of the world’s population, and by 2100 it will still be about the same, according to projections by the UN. During that same time, China’s share is expected to fall from 18% to 6%, while the European Union will go from 6% to 3.5%. And America will, in relative terms, be a younger country.

Ever-improving productivity, it should also be noted, will help the United States better cope with future demographic challenges than places that need more workers to generate the same (if they’re lucky!) amount of economic output. There is, as always, more that we can and should do on these fronts, whether it relates to automation, AI, immigration, or (free market!) family-friendly policy, but we’re still doing okay now as it is. And probably better than comparable economies abroad, too.

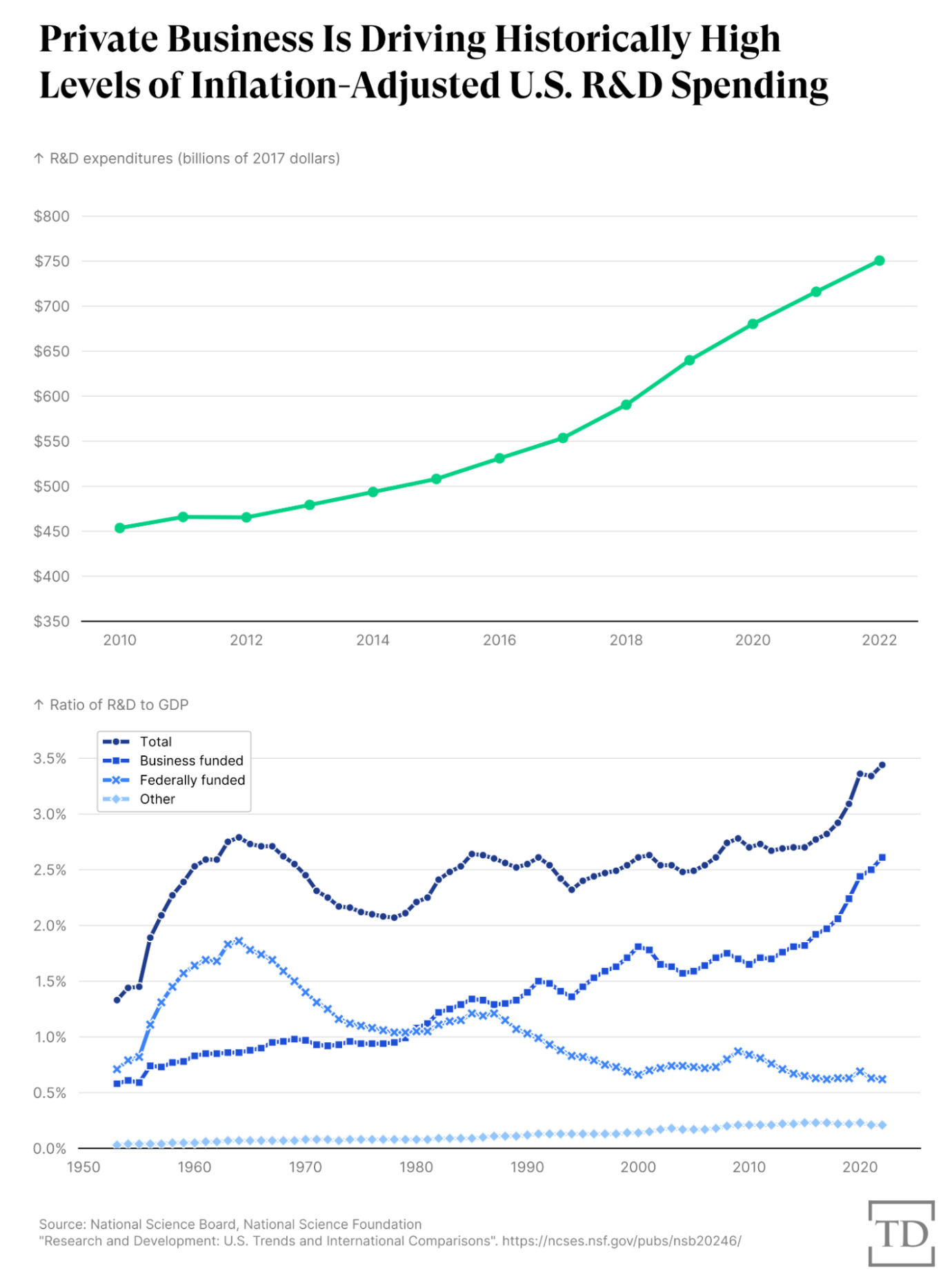

Beyond The Economist’s report, there’s other good news. For example, the latest report from the National Science Foundation shows that U.S. R&D spending in 2022 (the last year available and notably before the new U.S. industrial policy push really got going) climbed to a record high a few years ago and then just kept on climbing, driven almost entirely by private business:

Private spending, it should be noted, increased both applied and basic research (i.e., the stuff we’re told only governments do). And outside of a few smaller nations, such as Israel and South Korea, the United States today spends more on R&D—in both absolute dollar terms and as a share of GDP— than any other country, with big benefits for the economy. As The Economist notes, for example, R&D spending and other types of non-residential business investment give “American workers … more tools at their disposal,” thus boosting productivity, output, and wages that give us even more tools down the road. It’s a virtuous cycle.

Speaking of the American labor market, it too is strong both relative to other nations and historically. We discussed a lot of this already a few weeks ago, but this chart—showing the ratio of employed “prime age” workers to the total population of those same people—hopefully hits that home:

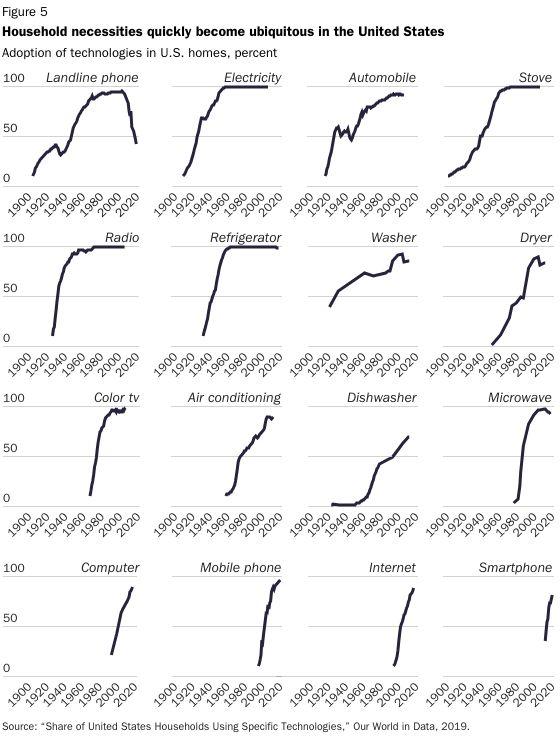

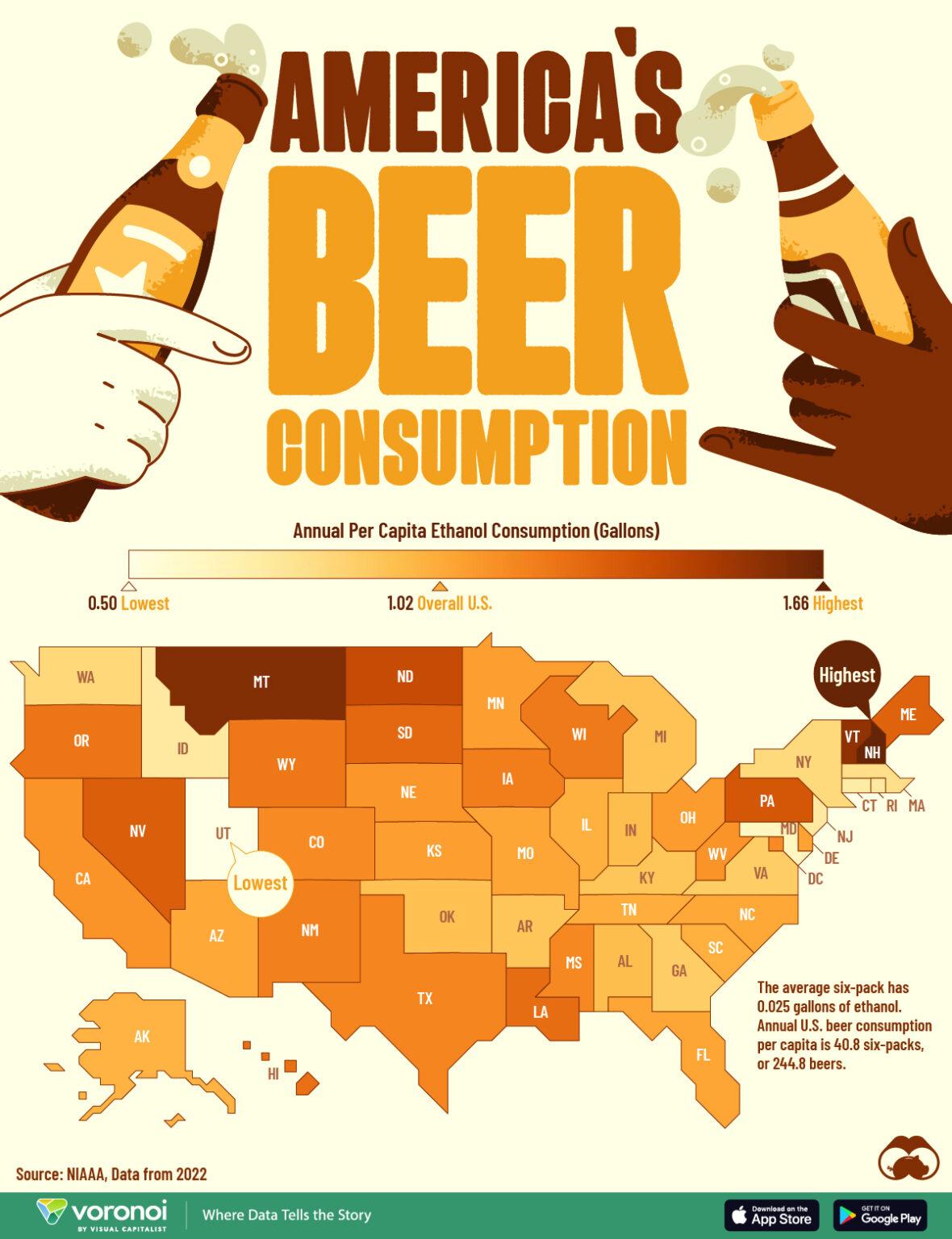

And, finally, I’d be remiss not to mention that America remains a true consumer paradise: whether it’s groceries or air conditioning or smartphones or TVs or clothes or basically anything else, the combination of a still-relatively open U.S. market and strong currency and economy allows Americans of all economic classes to afford things that were an unimaginable luxury for wealthy Americans just a few decades ago (and still are out of reach for billions of people around the world):

Thus, as certain measures of U.S. income inequality may have risen since the 1960s, consumption inequality has barely budged.

Meanwhile, Elsewhere…

All this isn’t to say, of course, that everything is perfect in the U.S. economy. There are surely some policies to be fixed, and perhaps the biggest economic storm cloud is our ever-increasing federal debt. As The Economist points out, one of King Dollar’s benefits is that it’s easier for the U.S. government to borrow gobs of money and still avoid a debt crisis. But this also has an obvious downside:

The simplest measure of a country’s fiscal health is its debt-to-GDP ratio. America’s has nearly tripled since the outbreak of the global financial crisis in 2007 to about 99%. The Congressional Budget Office, a nonpartisan scorekeeper, forecasts that it will soar to more than 160% over the next three decades. …Given the dollar’s centrality to global markets, America probably has even more room to run. But this also lets its political leaders off the hook from having to make unpopular decisions—namely, raising taxes and cutting spending—to rein in deficits.

Both Kamala Harris and Donald Trump are depressingly demonstrating that last point, with both promising big increases in the debt, even as entitlement programs and interest payments alone consume ever larger shares of federal spending obligations. With both major parties abandoning even the pretense of fiscal responsibility and at some unknowable future point, it’ll be a serious problem.

And yet, even with this and other economic challenges, the main real-world alternatives to the United States are inarguably in worse shape. China, as we’ve repeatedly discussed, is struggling mightily, thanks to a wicked combination of an enduring property crisis, ballooning (often hidden) debt, aging population, depressed consumer sentiment, dwindling entrepreneurship and foreign investment, a growing state-owned sector, high youth unemployment, bad economic planning, rising geopolitical tensions, stagnant productivity, and domestic political malfeasance (to put it nicely). Even the nation’s vaunted industrial sector, bolstered by gobs of government subsidies, is struggling “as deflationary pressures sap the strength of corporate finances.” Thus, as the Financial Times’ Martin Wolf just noted, worries about China’s “Japanification” have only increased since we covered it all last year, and, while total collapse isn’t in the cards, the overall “shift from the dominant narrative of the past 20-30 years — that China would inevitably catch up with and eventually eclipse the US as the world’s largest and most dynamic economy — couldn’t be starker.”

To which I’ll just say, Welcome to the party, pals.

Germany and South Korea have also been somewhat recently held up by certain (often manufacturing-obsessed) pundits as having economic models that the United States should emulate. Today, however, Germany’s export- and manufacturing-heavy economy is facing not just “its first two-year recession in more than two decades,” as The Economist notes, and related near-term problems (e.g., these VW factory closures), but also systemic ones that put its long-term economic future in doubt. This includes a continuing energy squeeze, declining labor competitiveness versus euro-zone peers, a shrinking working-age population, and stagnant productivity.

(So much for all those wonderful trade surpluses, huh?)

South Korea is also still struggling since we detailed its problems last year. Along with terrible demographics, Bloomberg noted last week that “South Korea’s economy barely managed to eke out growth last quarter following an earlier contraction, underscoring the risks from a softening export rally, broadening geopolitical tensions and a US presidential race that may impact trade-reliant nations.” The article goes on to note that other areas of the economy, such as domestic consumption and construction, have also been weak in recent quarters, while high government debt also remains a concern. And while the IMF expects Korea’s GDP to rebound next year, it still won’t best the United States.

IMF estimates aren’t everything, of course, but they’re useful to show long-term, high-level economic trends, and here we can see that—for the last several decades and maybe for at least one more—it’s been the United States first and everyone else second:

Eternal Pessimism, Again

All of this raises the questions of why America’s doubters have repeatedly and erroneously predicted that some other economy—Europe in the 1970s, Japan in the ’80s and ’90s, China just a decade ago (if not sooner)—would surpass the United States and why they’ve been proven so wrong time and time again. Partisans naturally credit their party and candidate of choice with the United States’ continued economic outperformance, but—given that America’s winning streak has persisted across decades and through multiple Democrat- and Republican-controlled governments—bigger, more systemic factors deserve most (if not all) of the credit. This includes things like geography, climate, natural resources, and form of government, but buried in The Economist piece are perhaps the biggest ones of all: our relatively free markets and resulting economic dynamism, which “pushes workers, entrepreneurs and investment towards more productive sectors”—and more profitable ones too.

For example:

In 2005 America’s biggest issuers of patents were Procter & Gamble, 3M, General Electric, DuPont and Qualcomm, while in the euro area they were Siemens, Bosch, Ericsson, Philips and BASF, according to Antonin Bergeaud, an economist at HEC, a business school in Paris. In 2023 in America there were four new entrants in its top five: Microsoft, Apple, Google and IBM joined Qualcomm. In the euro area it was almost all the same, with only Bayer displacing Siemens.

Churn benefits the labor market too:

In any given three-month period about 5% of its workers change jobs. In Italy it takes one year to get the same level of labour turnover. A study in 2020 by the OECD found that among citizens in a large sample of Western countries, Americans were the most likely to move elsewhere for new jobs. Decisions to move may partly stem from things that other countries want to avoid, notably America’s weaker union laws and its more limited support for the unemployed. But dislocation can be productive: those who switch jobs tend to enjoy higher wages than those who stay put, an indication that they have gone to companies and places which are making better use of their talents. The wage premium for job-switchers is especially true for women, youth and people with fewer skills.

Change, of course, can be difficult for those involved, but it means big gains for almost everyone over the longer term. And we’ve seen it again and again during the pandemic, as a U.S. economy hit by both domestic and global shocks has not only weathered them but rebounded even stronger than before (and more strongly than our global peers). For example, Federal Reserve economists in May credited U.S. labor market flexibility/fluidity and business dynamism (firm births and bankruptcies)—both of which were aided by relatively lax domestic regulation of workers and businesses—for our outsized GDP growth. Dynamism was also behind our recent and historic stock market outperformance, Asset Management firm Bridgewater Associates explained in July (using one of my favorite charts of the year). Immigration has, as we’ve discussed, boosted the U.S. labor market, and, as Bloomberg’s Justin Fox noted in June, the United States’ recent boom in labor productivity and growth has again been at least partly owed to light touch labor regulation and resulting churn: “what the US got was mass layoffs followed by a rapid economic comeback”—a stark contrast, he shows, to European regulation and continued sclerosis. (For those who find the U.S. approach inhumane or something, please recall that government pandemic-era support was still very generous overall and also note this new research showing that U.S. areas with more lightly regulated labor markets have suffered less from economic shocks than did more regulated areas.)

The pessimists, as we’ve discussed, miss all of this because they’re thinking statically. As a result, people and places disrupted by momentary economic shocks stay forever disrupted, and momentary trends continue forever in a linear fashion. They miss how market actors adjust and change, usually for the better—and, importantly, as long as government policy lets them.

Indeed, perhaps the biggest threat to the American Prosperity Machine is that American voters keep putting these pessimists in charge.

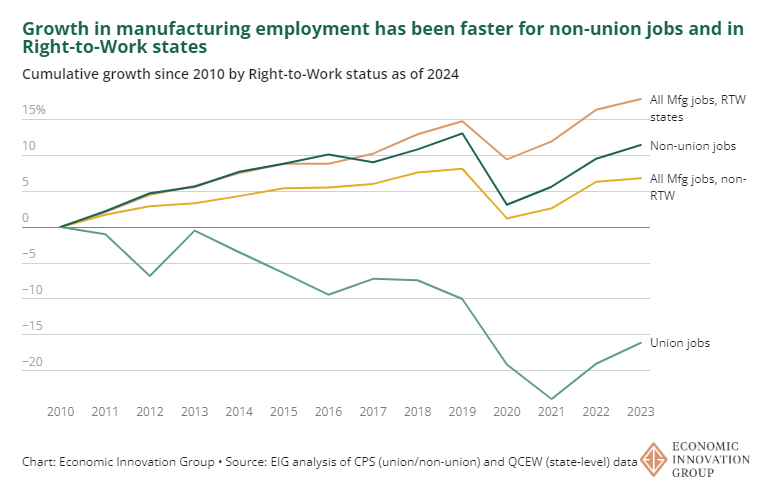

Chart(s) of the Week

Industrial policy won’t create an American manufacturing jobs boom or bring back “Rust Belt” union jobs (more)

The Links

Good WSJ editorial on tariffs (Sens. Toomey and Paul too)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.