Whether it’s children sporting pointy hats, Hocus Pocus playing on repeat, or homes adorned with bubbling cauldrons and broomsticks, witches are a hallmark of the Halloween season. And though their rich history may span cultures and time periods, witches seem to hold a uniquely captivating place in the American imagination.

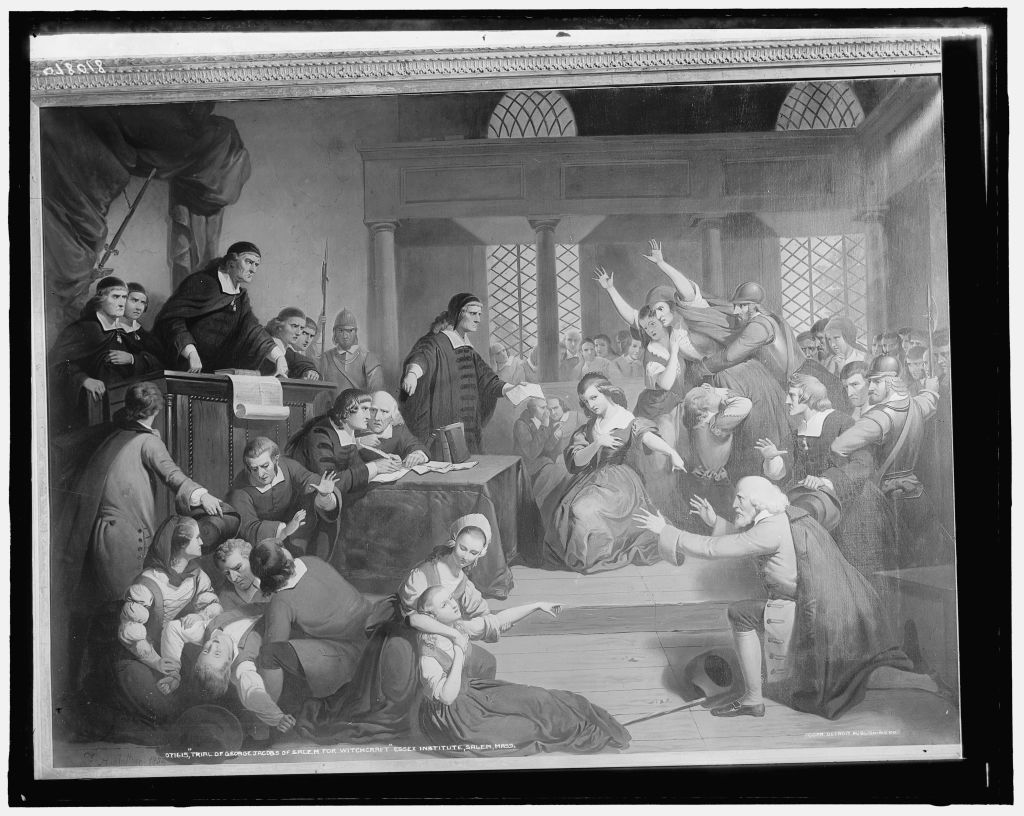

Yes, it’s largely because of the notoriety of the Salem witch trials. The infamous chapter has been repeatedly revisited through a stream of nonfiction accounts, Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, TV series like Netflix’s Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, and films like Robert Eggers’ The Witch. Centuries later, many present-day feminists draw parallels between then and now, casting the witch as a symbol of defiance and witch hunts as the price of challenging patriarchal authority.

But the history of witches is far more extensive. To understand it, we have to go back to Colonial America.

While Puritan clergy condemned magic as antithetical to the Christian faith, ordinary people often weaved it with religious belief in surprising ways. The clergyman Cotton Mather, for example, once lamented that some believers would let their Bibles fall open randomly, taking the first verse they saw as a sign of their spiritual state, which he condemned as divination. (Ironically, Mather himself had a keen interest in astrology.) As detailed by historians like David D. Hall and Richard Godbeer, many laypeople in Colonial America seemed to turn to folk magic not as a rejection of faith but as a practical way to navigate the world’s uncertainties.

But there was a real distinction between folk magic and witchcraft—and certainly a great worry about the latter. The difference for most in early New England boiled down to intent, harm, and perceived diabolical involvement. Folk magic (or white magic) aimed to heal and protect; witchcraft or maleficium (harmful magic) was defined by malicious intent and an alliance with the Devil.

Thanks to the work of historians like John Demos, we know a great deal about the types of people who were accused of witchcraft in Colonial America. Unsurprisingly, most were women, with a ratio of roughly four women for every man. Most came from lower social strata, often the wives of small-scale farmers or artisans with modest means. While high-ranking individuals like Mary Parsons, the wife of a wealthy landowner, were occasionally accused, they were rarely prosecuted, and even less frequently convicted. Contrary to the image of witches as old hags, those accused were typically 40 to 60 years old. They tended to have fewer children than the average New England family, with many having only one to three surviving children, compared to the typical six or more in most households.

Although women were more commonly targeted as Satanic practitioners, so were men at times. In E. J. Kent’s research on male witches, the accused often included small landowners, skilled artisans, and merchants. Though women were typically accused of practicing maleficium, men were more frequently linked to occult practices such as treasure hunting, fortune-telling, and invoking spirits for personal or social advantage. Women’s magic was often rooted in domestic and practical activities, while male witches were associated with more intellectual or “bookish” forms of magic, reflecting their societal roles and greater access to education.

Caleb Powell, a mariner from Newbury, fits this pattern well. Accused of practicing astrology and astronomy, Powell was rumored to have learned from a Quaker and claimed he could identify witches if partnered with another “scholar.” But this was not always the case, as the laboring John Godfrey—who was a contentious wanderer in Colonial Massachusetts—was rumored to wield magic not only to harm livestock but also to intimidate neighbors by exploiting his reputation as a witch.

Exploring why women were disproportionately accused of witchcraft has sparked ongoing debate among scholars. Historian Christina Larner even asked once “Was witch-hunting woman-hunting?” This question probes whether gender dynamics were at the heart of witch persecutions, and how broader factors such as religion, economics, and social expectations should also be considered.

For example, Elizabeth Reis argues that Puritan theology portrayed women’s bodies and souls as especially vulnerable to the Devil’s influence, with their personal failings interpreted as signs of having entered, knowingly or not, into a covenant with Satan. Carol Karlsen, however, emphasizes the importance of economic tensions, noting that many accused women occupied positions that disrupted traditional inheritance patterns. These women, often widows or daughters in families without male heirs, threatened the patriarchal system of wealth transmission by becoming potential inheritors of property.

Reis also emphasizes how accusations of witchcraft often targeted women perceived as assertive, argumentative, or nonconforming. In a culture that prized modesty and self-restraint, women who openly displayed anger, voiced dissatisfaction, or resisted traditional gender roles were seen as disruptive to social harmony. As a result, they became easy targets for suspicion and scapegoating, with their behavior framed as a threat to the fragile social order.

Paul B. Moyer argues that the circumstances of women’s lives played a pivotal role in shaping accusations and framing them as witches. Women’s domestic responsibilities—like caregiving, childbirth, and household management—positioned them at the heart of life’s most precarious moments, including illness, death, and social conflict—all of which were often linked to witchcraft. Demos adds a psychological dimension, pointing out that milk, cows, and babies held symbolic significance in early New England, as human breastfeeding and livestock milk were essential for survival. Witches, not surprisingly, were often accused of harming children or livestock, disrupting milk flow, or causing illness, reflecting fears around nourishment and livelihood.

The decline in witch trials also remains a topic of debate among historians, with varying perspectives on the factors that contributed to this shift. While the Salem witch trials dominate the popular imagination of American witchcraft, many other trials occurred across New England, albeit with far less fanfare. They often arose from personal disputes, family conflicts, environmental misfortunes, or broader community tensions. Contrary to dramatized portrayals of Puritans in modern media, acquittals in witch trials were more common than executions, as juries and magistrates frequently hesitated to convict based on ambiguous or circumstantial evidence.

Over time authorities grew increasingly cautious, often overturning convictions or avoiding death penalties altogether. Both the difficulty in proving diabolical involvement and the rise of stricter evidentiary standards undermined confidence in courts’ ability to prosecute witch trials effectively. This judicial skepticism intensified after the collapse of the Salem trials and marked a turning point, discouraging further accusations and contributing to the gradual decline of witch trials. Yet the decline in witch trials did not align with a decrease in belief in magic. As Owen Davies and others have demonstrated, interest in the occult persisted beyond the Colonial period, enduring through the founding of the nation and the Civil War, and continues to endure to this day.

Puritan fears may have faded from our culture, but the pull of magic remains. Interest has even grown among Gen Z, especially women, driven in part by the popularity of #WitchTok on social media and their embrace of what they perceive as a celebration of supernatural femininity. Similarly, “ex-witches” have become featured guests on Christian podcasts, sharing testimonies of their experiences with witchcraft, their subsequent conversions, and warnings about the dangers of occult practices.

As people keep grappling with the boundaries between faith, spirituality, and the occult, the witch continues to be a figure of fascination, mixing the darkest fears of the past with today’s spirit of rebellion. But whether she’s feared, celebrated, or just turned into a Halloween decoration, it seems like the American witch isn’t going anywhere.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.