Happy Monday! Know someone who loves The Dispatch and wants to share their passion for excellent journalism on a hat, sweatshirt, or mug? Check out our updated merch store (we’ve been drooling over the boxes of the samples at Dispatch HQ) and give them a gift that reflects their support for good, honest journalism.

Tomorrow is the last day you can order merch with standard delivery and guarantee arrival by Christmas Day.

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

- Syrian rebel forces took control of the capital of Damascus over the weekend, forcing the long-time dictator, President Bashar al-Assad, to flee to Russia on Sunday, and marking the end of his family’s half-century rule. Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, one of the main rebel groups that led the offensive, began as an al-Qaeda offshoot, and the U.S. currently designates it as a terrorist organization, although its leader has tried to publicly distance the group from its terrorist roots. President Joe Biden celebrated the fall of the Assad regime, calling it a “fundamental act of justice” and a “historic opportunity,” but he also emphasized the “risk and uncertainty” of the situation. Meanwhile, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Sunday that the Israeli military has temporarily seized control of a buffer zone along the Syrian border after Syrian army forces withdrew from their positions.

- The Romanian Constitutional Court ruled on Friday to cancel the results of the November 24 first round of voting in the country’s presidential elections following allegations that Russian interference affected the outcome. The court had initially validated the results in a decision earlier last week, and the runoff election was scheduled to be held on Sunday. But after Romanian intelligence and security officials declassified details of a widescale Russian campaign to influence the election, the court reversed itself. The ruling, a first in Romanian history, means the country will have to restart its entire electoral process.

- South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol dodged an impeachment vote on Saturday after lawmakers from his People’s Power Party boycotted the vote. But the party’s leader, Han Dong-hoon, claimed Sunday that Yoon would step down and the country’s prime minister would manage the president’s responsibilities in the interim. “The president will not be involved in any state affairs including diplomacy before his exit,” he said. It was unclear as of Monday morning if Han was speaking for the entire party and whether Yoon had agreed to step down. Opposition lawmakers criticized the plan for the prime minister to step in, saying Yoon should resign immediately or be impeached.

- The D.C. federal appeals court on Friday upheld the law requiring TikTok to be divested from its Chinese ownership or else face a ban in the United States, rejecting TikTok’s challenge to the law on free speech grounds. “The First Amendment exists to protect free speech in the United States,” Judge Douglas Ginsburg wrote in the majority opinion. “Here the Government acted solely to protect that freedom from a foreign adversary nation and to limit that adversary’s ability to gather data on people in the United States.” TikTok suggested it plans to appeal the decision to the Supreme Court, but barring that appeal, or a sale of the company to bring it into compliance with U.S. law, the app is scheduled to be banned in the U.S. beginning on January 19, 2025.

- In his first post-election network television interview, President-elect Donald Trump on Sunday outlined some of the top priorities for his second term. The president-elect told NBC News’ Kristen Welker that he still plans to end birthright citizenship on day one of his presidency—citing only “executive action”—and will “most likely” pardon people convicted for their involvement in the January 6 attack on the Capitol, possibly with “some exceptions.” Trump reaffirmed his intent to pursue widescale deportations of illegal immigrants beginning with people who have criminal records but widening deportations to include the millions of people here illegally. He also said he wanted to work with Democrats to come up with a plan to allow “DREAMers”—people who were brought to the U.S. illegally as children—to stay. Trump also said he has no plans to ask Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell to step down, despite criticizing Powell earlier this year and claiming the Fed’s monetary policy was intended to help Democrats’ electoral chances.

- Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said Sunday that 43,000 Ukrainian soldiers have been killed and 370,000 wounded since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, marking the first official accounting of Ukrainian losses since February, when the death toll was put at 31,000. The figures came a day after Zelensky met with President-elect Donald Trump in Paris. “Zelensky and Ukraine would like to make a deal and stop the madness,” Trump wrote on Truth Social following the meeting, which Zelensky simply described as productive. Meanwhile, the Biden administration announced a nearly $1 billion military aid package to Ukraine on Saturday, the 22nd package the administration has sent via its Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative, which gives Ukraine the ability to purchase capabilities directly from U.S. defense contractors.

- Mass protests in Georgia against the ruling party Georgian Dream’s decision to suspend European Union membership talks continued into their 11th straight day on Sunday. Thousands of people have taken to the streets even as authorities have carried out an increasingly violent crackdown that has drawn condemnation from European officials.

Assad’s Regime Is No More

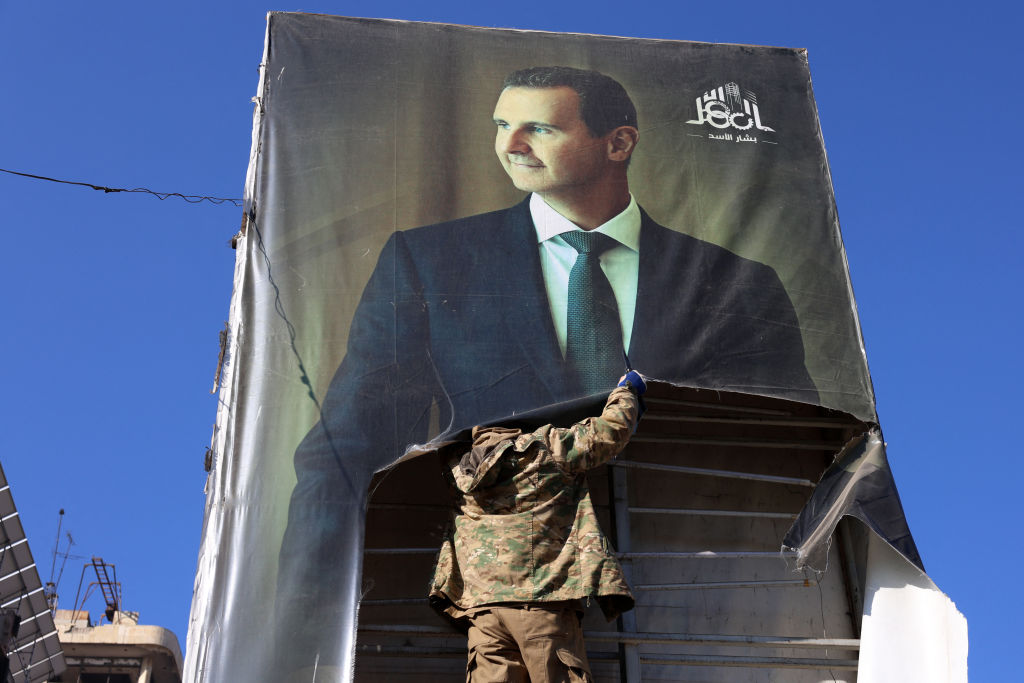

Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad—responsible for sweeping human rights abuses, brutal repression, and crimes against humanity perpetrated against his own people—fled Syria on Sunday in what marks the end of more than five decades of the Assad family’s despotic rule.

Assad’s ignominious departure signaled the toppling of the Syrian government after the rebel coalition’s surprise, rapid-fire advance across government-held territory. Now, the ground is shifting in Syria, but it’s not clear what the landscape will look like when the tremors stop.

The Syrian civil war started in 2011 and had seemed more or less frozen in recent years, but warmed up again late last month as a coalition of Syrian rebels—led by the Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)—launched a blitz across government-held areas. In city after city, the government forces fell away with little serious resistance. In just three days, the rebels had taken Syria’s second-largest city, Aleppo—the first time they’d set foot there since 2016. Days later, they took Hama, a key city on the road to the capital, Damascus. Next, rebels took Homs, the final major obstacle before reaching Damascus on Sunday.

As the rebels closed in, Assad went knocking on the doors of his allies in Moscow and Tehran, presumably trying to gin up the kind of support from Russia and Iran that had helped keep him in power for the 13 years since the initial uprising against his rule.

Russian fighter jets did drop bombs on Aleppo and other rebel-held territories in recent days, but it wasn’t sufficient to stop the coalition’s advance. As Charlotte explained in a piece on the site last week: “Moscow has reportedly moved at least some military assets out of Syria amid its fight with Ukraine. Perhaps more importantly, however, it has also failed to adequately train Assad’s forces to defend themselves under an organized and sustained rebel offensive.”

And so, as rebels reached the capital, Assad and his family fled. Where? To Moscow, of course, where the Kremlin granted them political asylum.

In the streets of Damascus and cities across the country, Syrians cheered the end of five decades of Assad rule. They toppled statues of Assad and his father, who was president before Bashar; they ripped down propaganda posters bearing Assad’s image and, often, the words “Assad forever”; and they tore the Syrian government flag into shreds. In Latakia, a regime stronghold on the Mediterranean coast, Syrians rode a statue of Assad through the street like a sled as it was dragged behind a pickup truck. In the capital, celebratory gunfire rattled through the streets as people cheered and waved the flag of the opposition.

How did the rebels pull it off? During four years of uneasy—and still fairly violent—stalemate, the rebel forces had been training up, according to the leader of the HTS, Abu Mohammad al-Jolani. “In recent years, there has been a unification of internal opinions and the establishment of institutional structures within the liberated areas of Syria,” he told CNN last week. “This institutionalization included the restructuring within military factions. They entered unified training camps and developed a sense of discipline. This discipline allowed them, with God’s guidance, to engage in a battle in an organized manner.”

The question now is what comes next. Assad’s prime minister, Mohammed Ghazi al-Jalali, has said he is “ready to cooperate” with the rebels, who on Sunday reportedly escorted Jalali to the Four Seasons hotel as part of what purports to be a government transition. But it’s not clear what form a new Syrian government might take.

And just because Assad, credibly accused of deploying chemical weapons against his own people, is gone, doesn’t necessarily mean that what replaces him will be dramatically less extreme. Though it officially cut ties years ago, HTS, al-Jolani’s group that led the rebel assault, was once associated with al-Qaeda, and it remains a jihadist organization designated as a terrorist entity by the U.S. government. Al-Jolani has a $10 million U.S. bounty on his head. U.S. officials say many in the group maintain ties with the Islamic State, though the group has apparently offered verbal assurances through back channels that it doesn’t intend to allow ISIS to be a part of its movement. “We’re clear-eyed about the fact that ISIS will try and take advantage of any vacuum to reestablish its credibility, and create a safe haven,” President Joe Biden said Sunday. “We will not let that happen.”

Biden, in his statement from the White House, marked the encouraging, if precarious, moment. “The fall of the regime is a fundamental act of justice. It’s a moment of historic opportunity for the long-suffering people of Syria to build a better future for their proud country,” Biden said. “It’s also a moment of risk and uncertainty as we all turn to the question of what comes next. The United States will work with our partners and the stakeholders in Syria to help them seize an opportunity to manage the risk.” On Sunday, the U.S. military struck dozens of ISIS targets in eastern Syria, where some 900 U.S. troops are stationed as part of a mission to fight the terror organization. Israel is reportedly also striking Syrian military bases in an effort to destroy Assad’s remaining chemical weapons.

A new era, of unknown character, dawns in Syria this morning. “Both world and Syrian history suggest that what comes next could be ugly,” Walter Russell Mead, a scholar at the Hudson Institute, said Sunday. “Think Iraq. Think Libya. But the fall of Assad and the defeat of his Russian and Iranian enablers are good things. We can rejoice in this good news without losing sight of the potential downsides.”

Biden’s Hail and Farewell to Africa

During a visit to Angola last week, President Joe Biden spent several days trying to make the case that Africa would be a key part of U.S. strategy going forward. “The United States is all-in on Africa,” he said on Tuesday.

“Africa is the future,” Biden proclaimed Wednesday. Too bad that until last week, neither he, nor any sitting U.S. president, had stepped foot on the continent since 2015.

Biden’s likely final diplomatic trip—and the first ever to Angola by a sitting president—was meant to signal the U.S. commitment to engagement with the continent in the unfolding era of great-power competition with China. But it’s yet to be seen whether the incoming Trump administration will have any interest in maintaining the Biden administration’s belated focus on sub-Sarahan Africa, and whether, even if it does, the U.S. can hope to outcompete China for influence there in the long run.

In an effort to advance one of the last policy initiatives of his presidency, Biden touched down in Angola last week. He spent three days in the sub-Saharan African country—which spent much of the Cold War more sympathetic to the Soviet Union than to the West—to highlight hundreds of millions of dollars in investment in one of the U.S.’s most ambitious development projects in Africa: the Lobito Corridor, a railroad running from the Angolan port of Lobito to the city of Kolwezi in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a regional center for cobalt mining.

The U.S. is not investing in Angola, or Africa more broadly, out of the goodness of its heart. Increasingly, the U.S. has economic and strategic interests in the world’s second-largest continent. Africa will drive much of the world’s population growth in the coming decades, projected to make up a quarter of the world’s population by 2050. Critical mineral rights in southern Africa will also be a crucial site of competition. The Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Zambia all hold massive reserves of minerals like lithium, cobalt, and manganese, used for rechargeable batteries key to the green transition, complex alloys for aircraft production, and consumer electronics.

The Lobito Corridor, financed by the G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Development, hopes to take advantage of those natural resources, exporting critical minerals from Zambia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo through Lobito and then into the Atlantic, toward the West. It’s a $5 billion investment, backed not only by the G7 but by companies in the U.S. and the European Union.

It’s also meant to be a belated counter to the persistent efforts of an adversary seeking influence in Africa: China. Emerging from various attempts to involve developed democracies and their private companies more closely in global infrastructure investment, the G7 partnership was announced in 2022 as a thinly veiled counter to Chinese development investment and financing. “It’s a chance for us to share our positive vision for the future,” Biden said at the 2022 G7 summit in Germany. “And [to] let communities around the world see themselves, see for themselves the concrete benefits of partnering with democracies.”

“We seek a better way, transparent, high standard, open access to investment that protects workers and the rule of law and the environment,” Biden said in Angola, hailing the Lobito Corridor as a harbinger of new, more effective investment in African economies. It was a veiled jab at China’s often less-than-scrupulous lending practices and a promise that America can be a better partner for developing countries.

Over the last few decades, Africa has increasingly become a destination for Chinese investment, Brad Parks, the executive director of the AidData Project at the College of William & Mary, an initiative that tracks Chinese investment and aid projects, explained to TMD. Part of that shift is a product of post-2008 changes in the global financial landscape. “When [the Federal Reserve] did quantitative easing, the rate of return that China was getting on its dollars in U.S. Treasuries went way down,” said Parks. “That was this moment of truth, because China’s central bank pulled huge amounts of dollars out of U.S. Treasuries, and then they gave those dollars to their banks, and they said, ‘go hunt.’”

Chinese money poured into Africa, picking up speed with the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative, launched in 2013, which sought to make China a major player in international development. Angola has been one of the countries most involved with China’s international turn. China has loaned the country $46 billion since 2002, sending money to projects like the forthcoming construction of a nearly 900-mile motorway running north to south.

Chinese aid isn’t without its caveats. A typical U.S.-led aid project might look something like the recent grant of $19 million to Namibia to support a fund financing hydrogen energy projects. In contrast, “when China gives grants or interest-free loans, the kinds of things that they support are really projects that are catering to the interests of governing elites,” said Parks. Zimbabwe’s palatial new parliament building, constructed for $200 million, is a more typical example of Chinese “aid.”

Rather the vast majority of Chinese projects in Africa take the form of business investment or market-rate loans. The results, for African countries, have been decidedly mixed. Those Chinese bankers sent to hunt abroad after the 2008 financial crisis did not, in fact, prove to be perfect judges of what were, and what were not, good investments. Angola, the largest recipient of Chinese loans, was no exception to this mixed record: As of 2023, it owed $21 billion to China. It took nearly half of Angola’s budget to service this outstanding debt, money not spent on its own citizens or economic development.

There’s an opportunity, then, for the United States to become a partner of choice for African countries, at least in certain areas, Parks said. According to AidData surveys, “leaders have a very strong preference for working with China in specific sectors,” he said. “They really want to work with them in the transportation sector and in the energy sector, and a big part of this has to do with implementation speed.”

U.S. infrastructure projects have tended to take far longer than their Chinese equivalents due to environmental and safety regulations. The Lobito Corridor, then, is a test case for whether America, prized for governance and environmental protection projects but not known for efficient railway construction, can supplant China in that crucial area. In fact, poor Chinese workmanship on the railway created the opening for the U.S.-backed consortium to win the bid to revitalize the economic corridor it created.

But infrastructure is not the only arena in which the U.S. can move towards becoming a more credible partner to African nations. “The US is very good at providing development assistance,” said Raphael Parens, an expert in African security at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. “We’re not very good at publicizing what we’re doing, or that we’re doing it.”

Parens also noted that U.S. companies will be extremely reluctant to make large-scale investments in African critical minerals until they feel assured of the security of their projects. “It’s pretty hard to incentivize U.S. companies to invest in these countries where there is significant political risk, but also where there is such a high level of corruption that it’s incredibly hard to do business without involving yourself in corruption that would get U.S. companies in trouble.” Replicating China’s growing practice of enabling private military contractors (PMCs) to provide security for American companies may be part of U.S. strategy going forward.

There are also benefits to a more conventional military presence. While southern Africa does not have the same security issues as the Sahel—currently plagued by waves of jihadist violence—or Sudan—embroiled in a bloody civil war—that doesn’t mean that security cooperation with countries in the region is a waste of time. While southern Africa may be “lower down the list of priorities within the African continent,” said Colin Clarke, an expert in African security at the Soufran Group, “from a grand strategy perspective, you’ve got to compete. You have to be in the areas where your adversaries are.”

The questions the U.S. must answer going forward, then, are ones of credibility and commitment. In that light, Biden’s visit to Angola—pushed back and tacked onto the very end of his administration—might be viewed skeptically. “My whole question is the timing of it,” said Clarke. “It’s a trip to Africa while Biden’s a lame duck on his way out the door. It doesn’t seem to be attached to any kind of broader strategy.”

Former Ambassador J. Peter Pham, who was the United States Special Envoy to the Great Lakes region of Africa, and then to the Sahel, during the Trump administration, told TMD over email that there is an opportunity for the U.S. to embrace a more forward-looking Africa strategy, if it has the will.

“Having America’s competitors at a disadvantage is an opportunity to exploit—if we are pragmatic and nimble about it,” he told TMD, citing Chinese economic strains and Russian mercenaries’ defeats in Mali. “First, regrettably, often enough, African leaders turn to China, Russia, or other countries not because they want to, but because America is not present or does not offer what they need. You cannot compete if you are not there. Second, even when America is present, we often are not quick enough—our bureaucracy is not exactly agile.”

Whether the U.S. competes in Africa will come down to how much the incoming administration prioritizes the continent. In an interview with the New York Times shortly before Biden’s visit, Angolan President João Lourenço signaled an openness to working with Trump. “My opinion is that he deserves the confidence of the U.S. voters,” he said. “And he’s the one whom Angola and all the countries of the world will have to work with if they are to maintain relations with the United States.”

But that does not mean the door will close on continued cooperation with China. “The way they put it, is like either you are with the one or with the other,” Lourenço said in response to a question about China-U.S. competition. “That’s not the case. That’s not how we see it.”

Africa, then, is still waiting to see exactly what “all in” means.

Worth Your Time

- Writing for The Economist, Jesse Singal detailed the lawsuit brought against Johanna Olson-Kennedy, one of the world’s leading youth gender medicine clinicians, by a former patient who underwent gender treatment but has since de-transitioned. “Dr Olson-Kennedy is being sued by a former patient, Clementine Breen, who believes that she was harmed precisely by a lack of gatekeeping,” Singal wrote. “And many of Ms Breen’s claims appear to be backed up by Dr Olson-Kennedy’s own patient notes, which Ms Breen and her legal team have shared with The Economist. … The lawsuit’s defendants are Dr Olson-Kennedy, the gender therapist to whom Dr Olson-Kennedy referred her, the surgeon who performed the double mastectomy and 20 as-yet-unnamed ‘Doe Individuals’ who were agents, servants, and employees of their co-defendants.’ Ms Breen’s attorneys accuse them of medical negligence on a number of grounds, including an alleged lack of psychological assessment, poor management of Ms Breen’s mental health and a lack of concern about the effects of puberty blockers on Ms Breen’s bone health.”

- In an essay for the New York Times, Georgian writer Anna Japaridze and photographer Frankie Mills documented what’s been happening on the streets of Georgia in recent days and weeks. “In the capital city of Tbilisi, the gates of the Parliament building have been battered, its windows smashed and burning objects thrown through,” Japaridze wrote. “For more than a week, Rustaveli Avenue, the city’s central street, has been a nightly battleground of tear gas and pyrotechnics. Anti-government protesters hurl fireworks that explode over the heads of the special forces and the lights of laser pointers swarm like insects. People pry off anything that will come loose — benches, plant pots, construction hoarding—and feed it into makeshift fires or onto barricades. The state responds with water cannons and tear gas, which seeps down the avenue, stinging our eyes and throats. … But each day the fear of losing momentum increases, as does the fear of the state’s increasing fury.”

Presented Without Comment

Politico: South Korean President Says He Won’t Seek To Impose Martial Law Again, ‘Truly Sorry’ for Anxiety

Also Presented Without Comment

Reuters: Trump and Macron Can’t Let Go of Their Handshake Duel

Also Also Presented Without Comment

New York Post: Juan Soto Signing With Mets on Gargantuan $765 Million Contract As Yankees Miss Out

In the Zeitgeist

Following a devastating fire and painstaking restoration, the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris reopened on Saturday in a ceremony attended by dozens of world leaders.

Toeing the Company Line

- Ryan Brown, community and partnerships manager, will answer your questions in the December Monthly Mailbag (🔒)! Members can ask him about his job at The Dispatch and why he made the switch from the editorial team to the business side, Mitt Romney’s role in him meeting his wife, and why being a dad is the greatest job in the world.

- In the newsletters: Nick Catoggio unpacked why MAGAworld is rallying around Pete Hegseth’s nomination, Jonah Goldberg made the case for impeaching Joe Biden over the Hunter pardon, Chris Stirewalt drilled down on (🔒) the moderate Democrats and Republicans who outperformed the top of the ticket in competitive districts, and Megan Dent explored the faults of “gentle parenting” in Dispatch Faith.

- On the podcasts: Jonah ruminated on the true form of the flagship podcast, Jamie was joined by Jonathan Spyer on The Dispatch Podcast to discuss the rebel insurgency in Syria, Luis talked to Emma Camp and Christine Emba on The Skiff (🔒) about what recent pop hits have to say about modern dating culture, and Michael discussed (🔒) interfaith cooperation and religious freedom with Asma Uddin.

- On the site over the weekend: Jeffery Tyler Syck explained the true lesson of Wicked, Jessica Schurz took stock of Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour as it comes to a close, and Paul Miller explored two Aesopian and classical metaphors for the cultural position of conservative Christians.

- On the site: In this week’s Monday Essay, Nathan Beacom explores the writings of the Chinese philosopher Mengzi and his teachings on virtue.

Let Us Know

What do you think comes next in Syria?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.