During his first term, Donald Trump was one of the more supportive American presidents of Taiwan. Even before he was inaugurated, Trump took the unprecedented step of answering a congratulatory phone call from then-Taiwan president Tsai Ing-wen. After taking office, the Trump administration made more regular arms sales to Taiwan and cut some of the unnecessary red tape around interactions between the American and Taiwanese officials. But Trump has been far more critical of Taiwan this time around, and more active in early outreach to Xi Jinping.

The good news for Taipei is that Trump has turned to a number of Taiwan supporters for top national security jobs. Trump’s National Security Advisor Mike Waltz has asserted that “we need to move from strategic ambiguity to strategic clarity” on Taiwan. Similarly, Trump’s Secretary of State Marco Rubio stated of Trump: “He’ll do what he did in his first term and that is… continue to support Taiwan.”

The question is, of course, whether Rubio’s assessment is correct. Some attribute Trump’s prior support for Taiwan to the island’s champions who surrounded him eight years ago. Friends of Taiwan in key first-term positions included former Secretary of State and CIA Director Mike Pompeo, former National Security Advisers Robert O’Brien and John Bolton, former Deputy National Security Adviser Matt Pottinger, and former Assistant Secretary of Defense Randy Schriver. This time, however, all five are likely to remain outside the administration, and Trump’s own views on Taiwan appear to have shifted.

Trump has made a series of recent statements expressing frustration or skepticism toward Taiwan. He repeatedly accused Taiwan of taking “all our chip business” – an apparent reference to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. He also notes frequently that Taiwan is “9,000 miles away” from the United States and “right next” to China.

Trump’s attitude toward Taiwan may be influenced by some of his outside advisers who have deep business ties in China, most notably Elon Musk. Over one third of Tesla’s global sales occurred in China last year, leaving Musk vulnerable to various forms of Chinese pressure. In 2023, he asserted that Taiwan is “an integral part of China that is arbitrarily not part of China.” He has even gone so far as to suggest, in 2022, that China administer “a special administrative zone for Taiwan,” akin to Hong Kong, which has seen its liberties evaporate under China’s “one country, two systems” model.

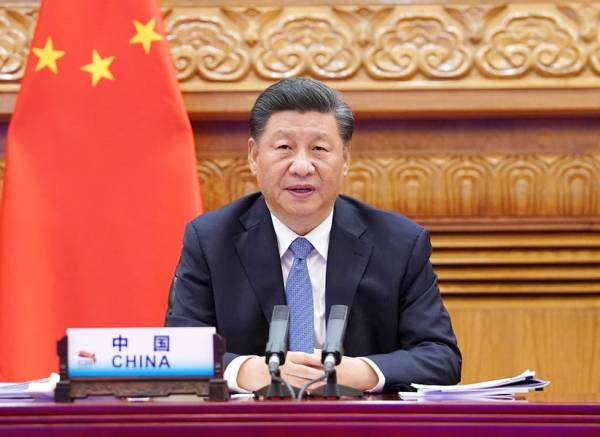

This does not necessarily imply that Trump would throw Taiwan overboard. But instead of early engagement with Taiwan’s president, this time around, Trump invited Chinese general secretary Xi Jinping to the inauguration itself. And not only was Elon Musk prominently featured, but the CEO of TikTok — upon which Trump has notably softened in recent months — sat next to Tulsi Gabbard, Trump’s nominee for the Director of National Intelligence. And in just the last week Trump has threatened tariffs against Taiwan’s leading semiconductor companies.

Predictable Unpredictability

This all adds up to one thing: unpredictability. Indeed, in many ways unpredictability has been a feature rather than a bug of Trump’s approach to foreign policy. Trump’s first Secretary of Defense, Jim Mattis, sought to mix predictability and unpredictability. In 2018, he argued the United States should be “strategically predictable for our allies and operationally unpredictable for any adversary.”

The Biden administration, on the other hand, prized predictability, seeing it as valuable for dealing with allies and adversaries alike. In private conversations, Biden’s team argued that predictability assured allies while deterring adversaries from testing U.S. commitments. Biden stated at least four times that he would side with Taiwan in the event of a Chinese attack against the island. He supported dialogue with China to clearly communicate U.S. positions on Taiwan and elsewhere, he reassured Russia that the United States would not send troops to fight in Ukraine or escalate in other ways without warning.

But avoiding surprises has downsides. As Richard Nixon’s famous “madman theory” implies, appearing predictable can make it easier for an adversary to calculate just how far they can go before triggering a response. Vladimir Putin has benefited greatly from this idea in Ukraine, where U.S. predictability has let him push ahead with minimal risk of escalation. And, critically for Trump, the same is true of allies – if allies know exactly what the United States is going to do, then they need not be as concerned about the threat of U.S. withdrawal of support. This in turn makes it harder to force allies to ante up and pay more for their own defense.

Academics sometimes call this the alliance dilemma. Leaders can maximize deterrence of an adversary at the cost of allied contributions. Or they can force allies to step up, but at the risk of weakening deterrence. There is no solution to this problem – only hard trade-offs. Whereas most U.S. leaders have preferred the former, Trump may well reverse this calculus in an effort to force greater spending by allies and partners — indeed, he has been a staunch critic of NATO countries that have not hit defense spending targets.

The question is whether Trump is truly unpredictable, or whether this is simply the “art of the deal.” Is unpredictability a negotiating tactic to force allies to pay more? Or does Trump mean what he says when he threatens: “You didn’t pay? You’re delinquent? … No, I would not protect you. In fact, I would encourage [the Russians] to do whatever the hell they want. You gotta pay.” For Trump’s approach to work, he must convince U.S. allies and partners that he really might abandon them. But adversaries like China will be watching, and this could make them more keen to test the new administration.

Arms for Influence

How is Taiwan responding to Donald Trump’s return to the presidency? President Lai Ching-te’s team has suggested that Taipei will submit a substantial weapons purchase request early in the second Trump administration. This could be doubly beneficial. First, it would signal Taiwan’s seriousness in the face of the mounting military threat from the People’s Liberation Army. Second, acquiring arms from U.S. manufacturers could be attractive to Trump, who has put a premium on increasing exports of American-made weapons.

But questions remain about whether this will be enough in the minds of the Trump administration. Indeed, Trump himself recently insisted that Taiwan “should spend 10” percent of GDP on defense, which would entail a quadrupling of Taiwan’s defense spending from current levels. But there are domestic political challenges that will make it difficult for Taipei to dramatically increase defense spending in the years ahead. Just last week, opposition lawmakers moved to freeze some of Taiwan’s military expenditures, largely for domestic political reasons. For Trump’s threats to work, they must be both believable and achievable as viewed from Taipei.

Indeed, some of Trump’s advisers have threatened to walk away from Taiwan if the government does not ante up. Elbridge Colby, Trump’s pick for under secretary of defense for policy, has called Taiwan’s spending “laggardly” and noted, “it isn’t sensible for America to bloodily forfeit its military in a losing fight, even for a very important interest. … Taiwan must dramatically change course, or we won’t have a real option to defend the island.”

Yet this message could undermine those pressing for more defense outlays. If even the highest politically realistic spending increases do not suffice for Trump, then many in Taiwan might simply give up hope, which could empower politicians who favor concessions to Beijing. After all, only one-third of Taiwanese view the United States as credible today, and nearly two-thirds say that a U.S. president’s public commitment changes their belief about whether U.S. forces would come to Taiwan’s aid.

Trump’s Taiwan policy therefore rests on a knife’s edge. His administration appears determined to shift America’s approach on Taiwan. But too much unpredictability could incentivize Beijing to test Trump’s commitment to Taiwan while convincing leaders in Taipei that additional spending will be insufficient to obtain American support. Properly calibrating this new strategy would require extraordinarily astute policymaking out of the new Trump administration. Although it may theoretically be possible to use unpredictability to America’s advantage, whether the second Trump administration can do this in practice is still very much up for debate. Unpredictability is a certainty. But what it means for Taiwan is not.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.