Franklin Foer’s The Last Politician: Inside Joe Biden’s White House and the Struggle for America’s Future channels the genre made famous by the Washington Post’s Bob Woodward: the close-to-simultaneous account of an administration’s inner workings. It’s a history—with an emphasis on the lower-case “h.”

That’s no surprise for a book of its kind. So much depends on whom the author is talking to and how much they are willing to divulge. If the individuals dealing with Iran or border security are tight-lipped or not made available, there will not be much about Tehran or Eagle Pass, Texas, to put on the page. A more definitive history of Biden’s early presidential years will have to wait until internal documents, oral histories, diaries, and memoirs make their way into the public domain.

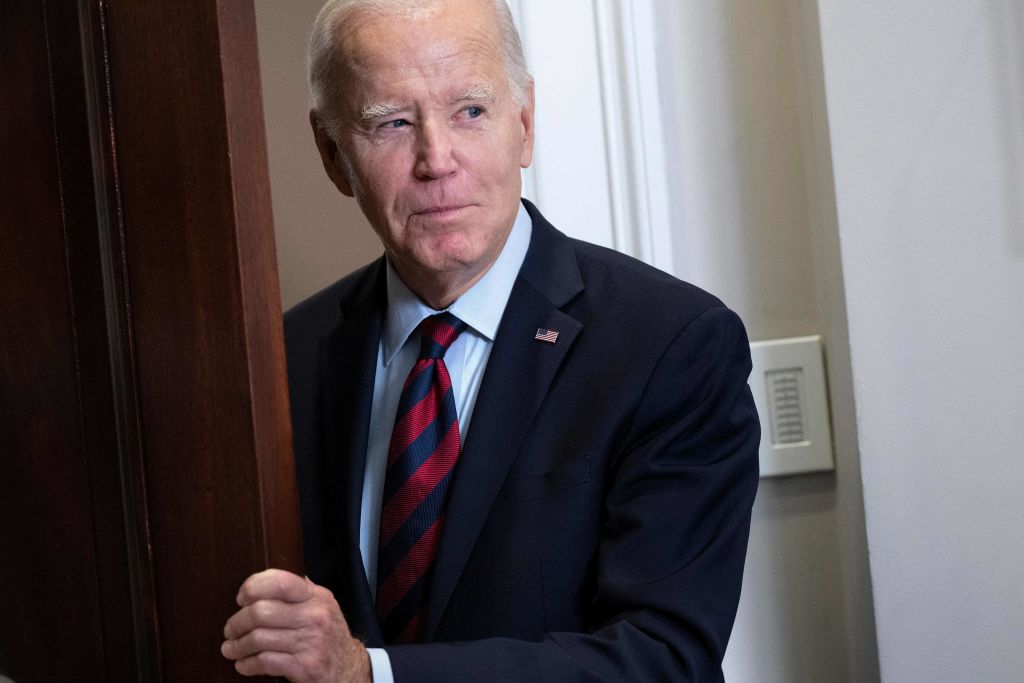

While The Last Politician may not be serious history, it is a remarkably honest account of Biden the president. Foer clearly depicts the boy from Scranton’s grand ambitions and just how temperamental, gaffe-prone, insecure, and obdurate the grown-up version has become. But although it’s no surprise that a president might have large ambitions or testy moments given the pressures of the job, there is a significant gap between Foer’s portrayal of Biden as president and the somewhat grandfatherly, empathetic, and personally decent persona that Biden the candidate—or even Biden of the inaugural address (“unity is the path forward”)—had presented to the country at large.

Foer’s central thesis argues that while Biden’s policy plans for the country were transformational—“passing monumental legislation, breaking with economic orthodoxy, redirecting [the country’s] foreign policy”—Biden’s methods for getting those plans enacted are old school. Biden was never going to be an “antipolitician” a la Barack Obama and Donald Trump, but rather a politician turned president who would be willing to debate, deliberate, cajole, and, if necessary, compromise to get what he wanted. Joe was a man of the Senate, it was said, and those habits would carry over into the Oval Office. But, as Foer admits immediately, squaring those ambitions (“proving himself great”) with “the tedious nobility of the political vocation” is not an easy thing to do.

Nor, in Biden’s case, was such a vision going to be realized because Biden was elected with no clear mandate—except to not be Trump—and with only the slimmest of majorities in the Congress. Moreover, given his age, Biden would naturally be a man in a hurry.

From both the White House’s and Foer’s perspectives, Biden’s first two years were largely successful at accomplishing his domestic agenda. Biden pumped massive amounts of money into the COVID-stricken economy with the American Rescue Plan; signed an equally massive infrastructure bill; sold the CHIPS Act on the promise to bring semiconductor production back home; and eventually passed the Inflation Reduction Act, which was more about fundamentally reordering the country’s energy infrastructure than getting its fiscal house in order. Much of this success, however, has come at a substantive and political cost. And it’s a cost that is directly related to Biden not acting as an “old pol” or, as he likes to say, an Article I guy.

Even if Foer himself never concedes it, Biden was never truly committed to the give-and-take required for a modicum level of bipartisanship. As soon as he entered the Oval Office, pen in hand, Biden issued a slew of unilateral executive orders over a 10-day period—an executive tool he would reach for repeatedly whenever the moment called for it. It seems Biden’s underlying intent for boosting the struggling, virus-infected economy was to spend more than double what President Obama had done in the wake of the Great Recession. Obama convinced Congress to give him nearly $800 billion in stimulus in 2009, a year into an 18-month recession. Despite the fact that the American economy had suffered just two months of an actual recession in 2021, Biden wanted nearly $2 trillion for his American Recovery Plan—never mind that Congress had authorized $4 trillion in pandemic relief spending before Biden entered office. Knowing that Republicans would never greenlight that amount of money or the many progressive programs that money would fund—and ignoring warnings about inflation from former Clinton and Obama administration cabinet official Larry Summers—Biden used the budget reconciliation process to bypass Republican senators and a potential filibuster.

Not satisfied with successfully passing the American Rescue Plan, Biden and his team quickly turned to the even more audacious and expensive Build Back Better. Filled to the trough with social programs, and with infrastructure and climate proposals, the $6 trillion proposal was to be Biden’s signature effort to fundamentally reorder a huge segment of the American economy, not to mention government’s role in directing it. Though never said outright, it was Biden’s way of topping Obama’s own signature win, Obamacare.

However, as Foer details, the proposed program was too much even for many within the Democratic Party. Blue Dog Dems in the House and, most famously, Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona balked both at the price tag and a number of the actual proposals. Foer’s retelling of the effort by Biden and his team to bring Manchin and others along, reveals just how much of a screw-up Biden was in his pursuit of those votes. A compromise bill did eventually get passed, but only because Speaker Nancy Pelosi took the reins from the White House in negotiating with the various House caucus factions, while in the Senate, Manchin and Majority Leader Chuck Schumer cut out the White House altogether. The president got his victory—but not because he exercised some latent legislative skill from his past.

The reality is that Biden can be bullheaded in the extreme. Presidents are expected to act decisively when necessary, but that decisiveness is not supposed to preclude serious deliberation before a decision is made. There is no better example of Biden’s self-destructive tendency to dismiss advice out of hand than his unilateral and precipitous decision to suddenly pull American military forces out of Afghanistan.

When the generals argued that a small force of 2,500 to 4,000 troops could adequately keep the security lid on, Biden’s rejoinder was that he understood the American military’s “emotional attachment” to the mission given the sacrifices that had been made. But he was determined not to be “talked into” staying, like Obama had been, for the “doomed cause” of nation building—even though no one was arguing then that that was the principal reason for staying. Biden was no less dismissive of allied concerns about the danger to Afghan women, and the likely summary executions of those who had cooperated with the West once the allied forces left. Biden argued that the Trump White House had reached an agreement with the Taliban to leave Afghanistan that he was obligated to keep—even though the political conditions set out in the agreement for leaving had not been met and although Biden had shown no previous qualms in overturning what the previous administration had done in other policy areas.

With seemingly no irony in mind, Foer begins his account of Biden’s decision to leave Afghanistan by recounting a 2002 encounter with a senior Afghan official who said, “We really appreciate that you have come here, but … Americans have a long history of making promises and then breaking them.” Then-Sen. Biden blew up at the official for his cheekiness, only for President Biden to confirm the Afghan’s worries 20 years later.

Biden’s roughshod ways have cratered his favorability among the American public. On Inauguration Day, Biden’s approval rating was in the mid-50s, with only 32 percent disapproving. That high point lasted only a few months. With the bloody and disastrous final days in Kabul, Biden’s favorability rating finally slipped below his disapproval rating. It has remained there ever since.

Two Biden successes that might have registered more positively with the public but didn’t are his nationwide rollout of the COVID vaccines and his support for Ukraine. The vaccine rollout really was a logistical performance of the first order. He also conducted something of a masterclass in rallying the democratic West to isolate Russia and thwart Putin’s effort to overturn the transatlantic security order. Interestingly, both are traditional exercises of executive authority where management competence and experience perform best, and where leadership needn’t be seen as transformative.

Nevertheless, when Biden caved to teachers’ unions over getting children back in schools, whatever gratitude the public might have felt over his administration’s show of competence with COVID wilted away. As for Ukraine, Foer has little to say about Biden’s reluctance to make a sustained public case for its strategic and moral importance, and how Biden’s continual hesitation to give Ukraine the weapons it needs in a timely manner has left the general public wondering what really is at stake. All of which has given critics of U.S. support the opening to talk about endless wars and the diversion of American resources at a time when Americans themselves are hurting.

It’s certainly true that none of this negativity cost President Biden as much as was expected at the ballot box in 2022. The Senate remained in the Democrats’ hands, and Republicans have a slim—and as we saw this week, dysfunctional—majority in the House. But that result was less about Biden and more about the galvanizing impact of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision, not to mention a reaction to the clown shows of Trump’s MAGA-supported candidates in what should have been very winnable races.

Early in The Last Politician, Foer writes that Biden has arranged the Oval Office to be a prop for his approach to the presidency and to governing. The most prominent place is given to a portrait of FDR, with the not-so-subtle suggestion that Biden’s own ambition is for his tenure in office to be as historic as Roosevelt’s. One would expect that an “old pol,” as Foer argues Biden is, would know how to count heads and how to read the country. FDR’s New Deal was made possible by a massive majority in Congress, and by a public wanting any help it could get in the desperate times of the Great Depression. Biden has never had either a Congressional majority of that size nor anywhere near a broad consensus for his preferred policies. But pursue them he did anyway, reinforcing the country’s partisan divide and stoking a level of inflation not seen in decades.

The consequence is that Biden’s policies have shaved whatever small margin he might have once had among moderates and independents, down to where even the widely unpopular, multiple-indicted Trump is currently running even with him in some polls. Biden might indeed be the “last politician,” but it will be because he has failed to be a good steward of that profession.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.