Defending the filibuster has been a core tenet of Republican Senate orthodoxy under Sen. Mitch McConnell’s time as party leader. But with an impending change in leadership, the GOP Senate conference might soften its full-throated support for the filibuster—it might even reform it. And one of the leading candidates to replace McConnell may have inadvertently made a powerful argument for doing so years ago.

That Republicans of an earlier generation instinctively defend the filibuster makes political sense. Between 1933 and 1995, Republicans controlled the Senate for just 10 years. They controlled the House for only four years. It’s no surprise that Republicans would come to view the prospect of congressional action with more fear than hope, or that they have looked to the filibuster—with the often insurmountable hurdle it poses to passing legislation—to allay that fear. But times have changed: Republicans have controlled the Senate for 16 of the 29 years since 1995.

Partisan interests aside, Republicans should also worry that congressional gridlock—to which the filibuster contributes significantly—strains the other branches of government with misdirected political pressure. In the face of congressional paralysis, presidents have aggressively interpreted existing statutory authority, especially where politics makes inaction untenable. The Supreme Court finds itself at the center of political controversy when it strikes down presidential overreach. That dynamic results from Congressional inaction.

Moreover, if Republicans don’t reform the filibuster to allow more legislation to make it to the president’s desk, frustration on the part of congressional Democrats and their base will continue to mount. Soon enough, Democrats might choose to eliminate the filibuster, not to pass legislation but to transform the Supreme Court—by packing the court or imposing term limits. (Note that the Democrats’ foremost defenders of the filibuster, Sens. Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, are leaving the Senate.) A continued lack of reform could lay the groundwork for full repeal—and a repeal with a far more destabilizing purpose.

In light of these dynamics, the case for reforming the filibuster in the interest of conserving our core governing arrangements grows stronger by the day.

Those like us who support conservative reforms to the filibuster that square with the framers’ vision of the Senate’s deliberative role should be heartened to know that a leading contender for Senate GOP leader has voiced frustration with the current state of the Senate. “I believe the Senate is broken—that is not news to anyone,” said Sen. John Cornyn of Texas last month as he announced he would seek the leadership post. “The good news is that it can be fixed, and I intend to play a major role in fixing it.”

Better still, Cornyn has voiced openness to certain filibuster reforms.

In a 2003 article published in the Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy, Cornyn argued emphatically against filibusters of judicial nominees. In doing so, he came out in strong support of majority rule as a first principle of American government. “The essence of our democratic system of government is simple: Majorities must be permitted to govern,” wrote Cornyn. He also approvingly quoted Alexander Hamilton in Federalist No. 22: “The fundamental maxim of republican government … requires that the sense of the majority should prevail.”

Granted, Cornyn took care in his article to focus on filibusters of judicial nominees in particular. He distinguished those from standard filibusters of legislation. “The extensive use of filibusters to defeat legislation throughout this body’s history stands in stark contrast … to the historical absence of filibusters of judicial nominations,” Cornyn wrote.

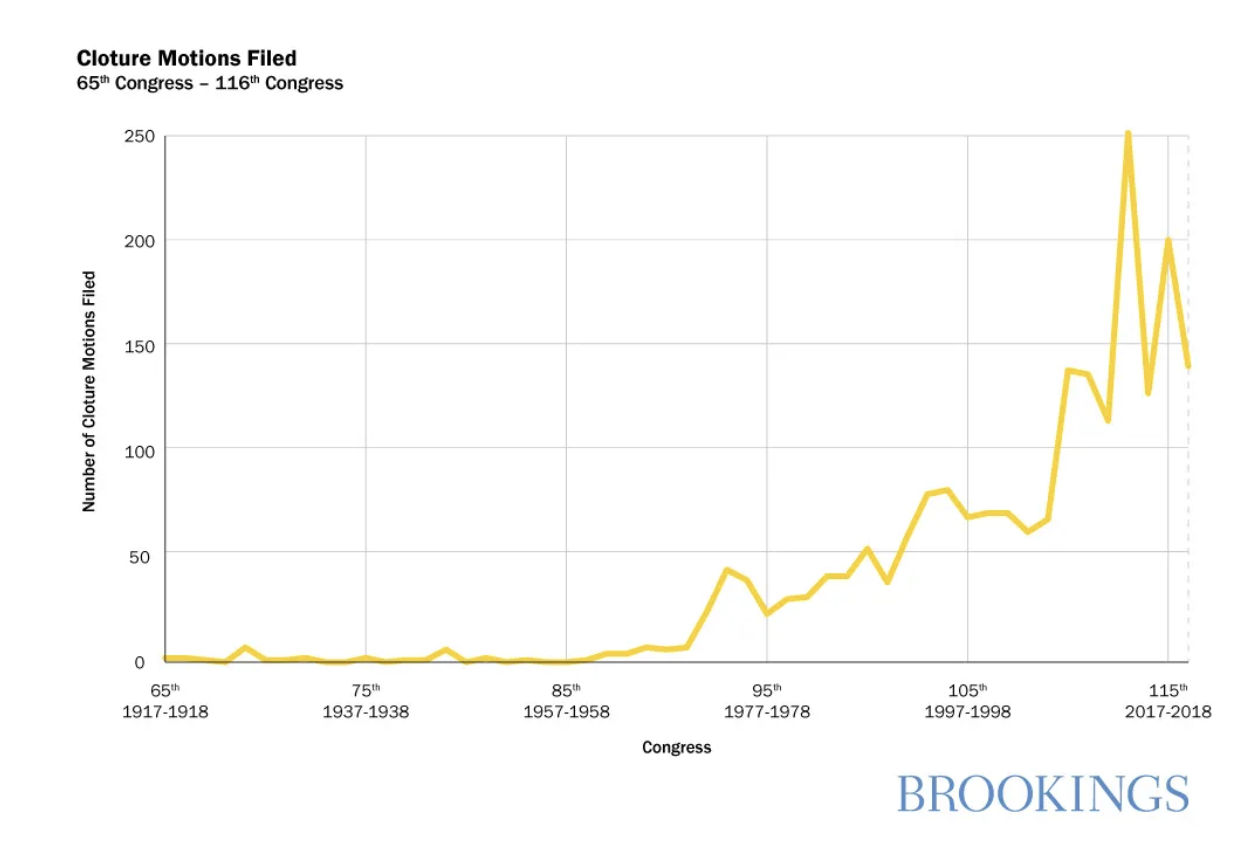

But Cornyn might be persuaded that the legislative filibuster’s historical pedigree is not that strong after all. Of course, the filibuster—or the use of prolonged debate as a procedural tactic—has been around since 1806. However, the use of the filibuster has taken off only in recent decades. Although it’s impossible to precisely measure filibuster frequency, the Brookings Institution’s Molly Reynolds explains that the frequency of cloture motions—motions to end debate and thereby allow a vote on the underlying question—is the best proxy. Those motions have skyrocketed in recent decades:

Sometimes, a difference in degree is a difference in kind. If Cornyn were persuaded that the current iteration of the legislative filibuster turns out to lack the sort of historical pedigree that warrants flouting, in James Madison’s words, “the fundamental principle of free government” that majorities must rule the legislature, then he might also be persuaded that filibuster reform should focus on fostering deliberation. After all, the best defenses of the filibuster align with the best defenses of the Senate itself: slowing down debate and giving people time to reason.

That’s exactly what we’re after when we propose that if a bill can’t obtain a filibuster-proof supermajority, the filibuster should be reformed so that the bill can still pass through the Senate if it obtains a simple majority twice—over the course of two successive Congresses, with an election in between. Cornyn’s original proposal for filibuster reform for judicial nominees back in 2003 shared similar impulses. He proposed gradually lowering the threshold for confirming a nominee as the debate on that nominee progressed. In other words, the higher threshold at the outset would help ensure that there is adequate debate and deliberation before a final decision is made. But in the end, the majority would govern. It’s the American way. Explicitly baking in a cooling-off period (like an intervening election cycle) prior to a definitive simple majority vote does the same trick.

Cornyn also noted that there are strong constitutional arguments that “a majority of Senators retains the constitutional right at least to adopt rules abolishing or regulating the use of the filibuster.” Therefore, should Cornyn be persuaded of the need for this conservative filibuster reform, his past writings also indicate that he agrees with us that there’s no need to resort to the nuclear option to accomplish it: a simple majority of senators has the power to change its rules and reform the filibuster at the outset of a legislative session.

Of course, much has changed—in the GOP, the Senate, and the country—in the intervening years. It’s possible that Cornyn’s view of the filibuster, and openness to reform, has shifted too. But the need to reimagine how to make Congress more effective and deliberative remains as important as ever.

Cornyn has spoken in the past about how the filibuster gives both parties peace of mind: In 2013, he said that whatever a filibuster-reforming party does “to the minority is what they will have to live with in the future” when they inevitably lose their majority. But another way of protecting one’s party and policy priorities going forward is by provisionally passing popular legislation, campaigning on the basis of that proposed legislation, winning election as a result, and then passing that legislation for good. That’s the route the GOP should take when it comes to filibuster reform. It will ward off the destruction of the filibuster by Democrats and prevent frequent rushes to cram through highly partisan legislation, which Cornyn rightly worries about.

It also would place Republicans in a far more powerful rhetorical position to combat Democrats’ argument that democracy requires a wholesale repeal of the filibuster: If Democrats are concerned about democracy, Republicans could argue, why not give the American people a chance to sign off on the majority’s legislative agenda by voting it back into office after the public knows exactly what it plans to do? The majority could rule, but only after voters approve its choices.

The greatest Republican, Abraham Lincoln, said in his first inaugural address: “The rule of a minority, as a permanent arrangement, is wholly inadmissible.” Americans still share those same democratic impulses today. Republicans can reform and preserve the filibuster while still claiming the mantle of democracy. That’s critical. As Lincoln said, in America, “public sentiment is everything. With public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it nothing can succeed.”

Sometimes, “we must reform in order to conserve.” So it goes with the Senate filibuster. Should he become the next Senate GOP leader, hopefully Cornyn will agree. His past writings on filibuster reform provide some reason to hope that he will.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.